On the trail of Australia’s most infamous treasure hunter

He claimed credit for discovering Australia’s oldest shipwreck. But colourful treasure hunter Alan Robinson left behind an explosive legacy.

“Stop the boat. I’ve found it.” Years of research and exploration, and finally a eureka: a weary arm raised and an “ungodly yell” from astern a drifting dinghy. At about 3.30pm on May 3, 1969, Australia’s oldest shipwreck had been located 17km west-north-west of Western Australia’s Montebello Islands. White water surged. Reef sharks circled. But an exuberant dive by all members of the party revealed a huge field of 347-year-old wreckage: anchors, cannon, ingots, bricks, sheeting, musket balls and a bronze rigging sheave that was the first item retrieved.

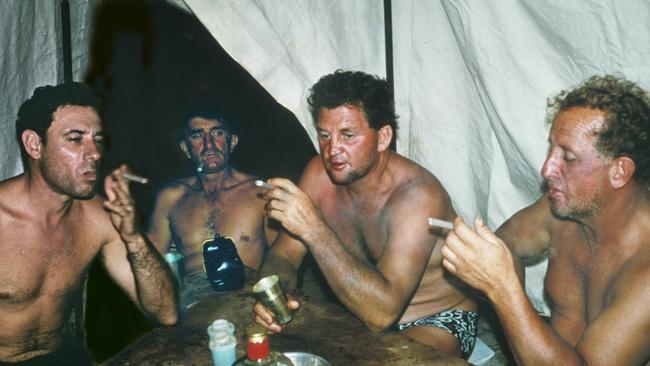

Celebrations continued in the venturers’ beach tent that night on North West Island. Beers were opened, cigars lit. A photograph captures the group’s weary elation, their bronzed torsos and briny hair: Dr Naoom Haimson, who had first set eyes on the wreck at the end of his shift while being dragged behind the dinghy, sat around a table with Dave Nelley, Alan Robinson and Eric Christiansen. The toast was raised: “To the Trial!” They would never again be so unified.

Even now, comparatively little is known about the Trial, an East Indiaman dashed against submerged rocks that now bear its name at 20° 17’ South 115° 22’ West on the moonlit night of May 25, 1622, a century and a half before Captain Cook, predating even the fabled Batavia and Zuytdorp. No illustration of the ship survives; its dimensions are unknown, although it was probably no more than 30m long and 7m wide.

Which is surprising for a ship so significant. The Trial was the first English vessel to sight Australian shores; its bedraggled survivors were the first Englishmen to set foot here. But there is no macabre terrestrial sequel, like Batavia, or seabed “carpet of silver”, as with Zuytdorp. Nor was the first English encounter with Australia a grand narrative of exploration; rather was it a combination of capitalist project and navigational accident.

Trial, crewed by 143 men, left Plymouth for Java on September 4, 1621 attempting a route newly pioneered by the Dutch, whereby ships bound for the Indies, rather than hug the east coast of Africa, could catch the Indian Ocean’s strong westerlies before turning north, halving journey time and enhancing profits. Trial carried provisions for a company outstation; all being well, it would have returned laden with spices.

A hundred years before reliable chronometers, however, longitude was dangerously inexact. Master John Brookes essentially missed his turn by 600 miles. On May 1, 1622, the crew sighted a peninsula later named Point Cloates, 100km south-south-west of WA’s North West Cape (“we were all verie joyful at the sight thereof”) but in diverting for Java encountered weeks of headwinds. These had barely abated (“faire weather and smooth wetter”) when Trial struck a craggy limestone pinnacle about 2m below the surface. The crew, claimed Brookes, panicked: some “would not beleave that she stroke” in apparently open sea and remained “a mayse”, while he made “all the means I could to save… as manie… as I could” in the ship’s skiff: these amounted to 10, including his son. Buffeted by surging tides, the Trial broke up just before dawn, sweeping 97 men into the sea.

In the meantime, however, a second party of 36, marshalled by company factor Thomas Bright, had managed to escape in the Trial’s long boat. Bright’s account of the ship’s last moments differed markedly. He claimed that Brookes departed “with fayr words promising us faithfully to take us along, but like a Judas… lowered himself privately into the skiff” without “seeing the lamentable end of the shipp, the time she split, or respect of any man’s life”.

Bright’s party put in for seven days on North West Island, encountering “not any inhabitants thereon” before following Brookes’ skiff on the 2000km open boat journey to Batavia. Remarkably, the two parties arrived just days apart; more remarkably, the difference between Brookes’ and Bright’s accounts seems not to have had serious consequences. Not until 1936 would maritime historian Ida Lee disinter them from India Office records.

Brookes’ behaviour, it transpired, had been more infamous still. To obscure his recklessness, he had falsified the location of Trial Rocks so that searchers were foiled for more than three centuries, to the point of wondering whether they even existed. It was Lee who hazarded that they were a site by then known as Richie’s Reef. But it would take another generation to be sure, and the wreck has surrendered few secrets since.

An aerial magnetometer survey flown over Trial Rocks 14 months ago preluding a three-day site inspection – the first official dive in 36 years – recently added to the sum of knowledge. Its findings are being kept confidential until Disney+ airs an episode of Shipwreck Hunters Australia later this year. But the legacy of the Trial involves narratives as contested as the original disaster.

There are about 7500 shipwrecks in Australian waters. Until the 1950s they were virtually inaccessible. Then, liberating and glamorous, came the scuba revolution. Jacques Cousteau directed The Silent World, Hans Hass Under the Red Sea; Howard Hughes attached an oxygen tank to a swimsuited Jayne Russell in Underwater. No Australian state felt scuba’s impact so profoundly as Western Australia, with its 13,000km of coast, and enthusiasm for spearfishing. Perth’s Underwater Explorers’ Club (UEC) is among Australia’s oldest, founded in 1954. The Daily News funded an expedition to dive on the Zuytdorp, wrecked in 1712, a few months later.

The Daily News front page on September 18, 1957 seemed to herald a new chapter in the unfolding undersea tale. In “We Look at the Wreck at Lancelin” reporter Hugh (“Groper”) Schmitt narrated how two enthusiastic “spearos”, Alan Robinson, 30, and Bruce Phillips, 18, had been diving off the fishing vessel Marion slightly north of Ledge Point, 80km north of Perth near the flyspeck town of Lancelin, and made “what could be the underwater discovery of the century”: the wreck of the Gilt Dragon, a Dutch East Indiamen known to have struck a reef in the vicinity on April 28, 1656.

By Robinson’s account, it was Schmitt who first suggested the ship’s identity but Robinson embraced the idea wholeheartedly. The Daily News story was a sensation. “Now I realised how men would react in a gold rush,” Robinson recalled. But when he and Phillips retraced their steps with Schmitt and photographer Maurie Hammond aboard the Marion, they couldn’t find the wreck again. Robinson became a laughing stock. The humiliation begat an obsession. He quit his Perth sales job, and, leaving his wife and children behind, started roving back and forth over the area from a one-bedroom shack in Lancelin.

Later he found a partner in his searching, another enthusiastic UEC member, John Cowen. With Schmitt, Hammond, and fellow journalists Hugh Edwards and Jim Henderson, Cowen co-owned a four-metre bondwood boat, Four Freedoms. Robinson invited them to dive Ledge Point and he was with Cowen, Henderson and Henderson’s teenage sons Graeme and Alan when Four Freedoms dropped anchor in shallow water on the north-west side of the reef about 5km off the coast.

Fatefully, Robinson did not dive. He explained later that he had wanted “to do some work on the motor”; others reported he was hung over. On his dive, 15-year-old Graeme Henderson saw what he first took for a boat. “There were these curved ribs,” he recalls. “Turned out that they were dozens and dozens of elephant tusks. Also hundreds of bricks.” They were cargo and ballast of the Gilt Dragon. Cowen returned to the surface brandishing a brick. “Robbie,” he said cheerfully. “We’ve found your wreck.” At first, Robinson was sceptical; gradually, he grew enthused. “And everything started to explode from then,” recalls Henderson.

Had the wreck been discovered or rediscovered? In Robinson’s mind, press attention accorded the young divers was rightfully his. It proved a breakthrough year for the diving community. Edwards had just dived the Zeewijk. Six weeks later, Max and Graeme Cramer located the long-lost Batavia while diving on Morning Reef. But Robinson felt sidelined: “The stories continued with my name gradually being omitted and my contribution forgotten.” When he registered the find with the receiver of wrecks, he ignored standard diving protocol, which was to include everyone involved in an expedition, and did so in his name alone.

This antagonised Graeme Henderson’s father Jim, a formidable character – suave, charismatic, among newspaper contemporaries known as “Mr Ego”. Henderson and Robinson developed a strong mutual antipathy following the day Henderson rose from a free dive on the Gilt Dragon to find Robinson raining blows on his head. Henderson alleged that Robinson was shouting: “You and WA Newspapers trying to steal my wreck… I’ll fix you, I’ll blow it to kingdom come.” Whatever the case, explosives were in Robinson’s plans. He planned to disgorge the wreck’s plentiful silver. Locals began hearing muffled explosions. Visitors reported damage. “What we found was a disaster,” recalled Jim Henderson. On one occasion late in the year, Robinson pointedly discharged explosives while Jim and Graeme Henderson were in the water nearby.

Graeme recalls it vividly: “I felt it. I felt myself rise in the water, and John Cowen who was there said there was a loud bump on the metal hull of a dinghy. My presumption is that it was his [Robinson’s] way of telling me to f..k off, that it was his wreck. And it was quite effective. It meant that my father was not keen for his 16-year-old to be swimming in the vicinity of a madman.” He estimates Robinson harvested a ton of silver from the wreck.

Yet Robinson was within his rights to do so. The urge is ancient. “Shipwrecks bring free loot,” observes Bella Bathurst in her classic history The Wreckers (2005). “And people like free loot.” Even using explosives at sea was not so unusual. In The Silent World, Cousteau cheerfully dynamites a reef.

A rift emerged between those who saw wrecks as history and as treasure. The Hendersons were among those who argued for the former: what the eminent Perth historian Geoffrey Bolton called the tendency of Australian history to be “made in the west and written in the east” provided a patriotic motivation. Jim now advanced his son Graeme as the wreck’s discoverer.

The Museum Act Amendment Act, passed in November 1964, vested control of all wrecks in the WA Museum and provided that discoverers of a wreck “shall not remove, damage or destroy the historic wreck or any part thereof”. Says Jeremy Green, who established the museum’s department of maritime archaeology after arriving from the UK in June 1971: “It’s a very remarkable thing that a group of divers should have turned to the government and said: ‘We’ll give up our rights if you legislate to protect.’ It’s the world’s first underwater cultural legislation.” But support was far from unanimous. At the time the WA Museum’s archaeological expertise was minimal and it was unclear whether WA was constitutionally empowered to make laws dealing with the sea.

Robinson carried on regardless. In his submariner’s white rollneck, he looked the very image of a diver. As secretary of the UEC from September 1964, he thrilled the press with talk of secret discoveries and shapeshifting schemes. In The Herald on January 18, 1969 he announced plans to locate the undiscovered Trial, about which mystery swirled, not least because the Montebello Islands had hosted three British atmospheric nuclear weapons tests between 1952 and 1956. Said The Herald: “Mr Robinson is not so much interested in the ship but what was aboard – about half a ton of gold.”

In fact it was unclear what the Trial contained: its cargo manifest included silver reals (coins) and jewelled ornaments, but there also exist hints that Master Brookes, unscrupulous as well as incompetent, pocketed these himself. Nor had Robinson been the Trial’s sole seeker. Amateur historian Eric Christiansen had teamed up with John McPherson to study the historical record first exposed by Ida Lee. Christiansen ultimately threw in his lot with Robinson, who in April 1969 persuaded television station TVW-7 to subsidise an expedition’s expenses in a contract that boldly promised the station “10 per cent of any monies received from the sale of relics, coins or other materials received”.

With his television bankroll, Robinson bought a broken-down one-ton Morris truck, which he and Christiansen filled with supplies and nursed almost 1500km to Onslow at 20km/h. Robinson then chartered a Cessna from Barrow Island to take aerial photographs of the target area. Joined by Naoom Haimson, a Perth doctor, and Dave Nelley, a water supply worker from Roebourne, the group shipped their gear to a small cove on North West Island aboard the fishing boat Quinda. The boat’s owner, Scruffy Blair, a nearly spherical local policeman who seldom wore more than a pair of underpants and avidly collected radioactive scrap, became a colourful addition to their complement.

The Montebellos are hot, bare and windy. In 1969 they were populated mainly by feral cats and black rats – the latter proved so menacing that the venturers erected platforms to keep their supplies off the ground. The location Christiansen recommended scouting was out of sight of land, in open ocean, infested with sharks and bedevilled by currents that could render divers helpless. At first it yielded nothing; then the foursome changed tack, taking turns being towed along the face of the reef so as to cover more area. They had been in and out of the water seven hours when Haimson raised his hand. “The wreck,” he said. “We’re drifting right over it.”

The group’s unravelling can be related in documents. On May 16, 1969, Christiansen filed with the museum a hand-lettered “Report of the discovery of a wreck site believed to be historic” in the names of all four divers. A letter 10 days later advising that Christiansen was the group’s “official spokesman” was missing Robinson’s signature. Christiansen submitted a lively account of the discovery to UEC News, later reprinted in Dive. But behind his back, Robinson grew fixated on taking sole credit for the discovery and tried to discredit his co-venturer. Christiansen sued for slander.

Still, the legal jeopardy in which Robinson soon found himself sometimes seemed disproportionate. His adviser, Eric Heenan, later a justice of WA’s Supreme Court, recalls: “I don’t think there’s any doubt that there was either an orchestrated or implied campaign to discredit Robinson. He was the target of endless denigration, and of more or less constant harassment by the police on minor offences that were either dropped or failed.”

Most serious were proceedings brought by the museum in relation to his handling of a ballast brick from the Gilt Dragon – essentially a test case for the Museum Act, pursued with curious vehemence. The museum had hitherto evinced no interest in ballast bricks, and with nowhere to store them had sent hundreds to the tip; Robinson had not even sold the item, just given it away. The charge aggravated Robinson’s sense of persecution. When police arrived at his home in Dianella, Perth, with an arrest warrant on January 12, 1970, he panicked and fled, leaving behind a collection of coins which the constabulary coolly confiscated.

Forces he had helped unleash now nearly overwhelmed Robinson. While he hid with a sister in the Perth suburb of Bentley, his long-suffering wife left him for another man. Police arrested Robinson when he assaulted the man with a baseball bat. He was remanded to Heathcote Mental Hospital. At length, Robinson elected to distance his pursuers. He took his 10-year-old son Geoff to Cairns, where he commenced a relationship with a woman, Lyn Hunter, mother of the champion Claremont and Carlton footballer Ken Hunter. He described her in his memoirs with erotic flourish: “A multi-coloured bikini only covered the barest essentials of her beautifully suntanned body.”

After a few months, however, the Trial’s lure grew too strong. Robinson enchanted four local prawn fishermen with tales of treasure. They sailed a 14m trawler, Four Aces, round the north of Australia to Trial Rocks, only to find the conditions inhospitable to diving. Robinson recalled: “It was as if we were being given warning to stay away from this 350-year-old graveyard.” An additional warning would have been handy: when Four Aces arrived at Shark Bay on June 20, 1971, Robinson was arrested for jumping bail and further charged with resisting arrest. He complained of being badly beaten.

Two weeks after Robinson’s ambush, a museum expedition arrived at Trial Rocks. This time surface conditions were inviting; it was the seabed that was alarming. Museum diver Geoff Kimpton recalls: “I got back to the boat and I said to Eric [Christiansen]: ‘Your wreck’s been blown to bits.’ Eric says: ‘That bastard!’” There was no ambiguity about whom he was talking. Further searches revealed the wreck to be strewn with detonators and explosives requiring the attention of clearance divers. The wreck could be surveyed only cursorily.

On July 19, while incarcerated in bleak and overcrowded Fremantle Prison, Robinson was further charged with “having wilfully and unlawfully used gelignite to cause an explosion likely to cause serious injury to property”. But when the case commenced in the Criminal Court, Heenan submitted overlapping arguments: that the Trial, far offshore, did not form part of Western Australia; that even if it did, the Museum Act was invalid. The crown case, moreover, was weak, the witnesses vague and contradictory. Acquittal took the jury only 15 minutes. Not only were the ballast brick charges dismissed, but Heenan successfully sued police for return of the coins, in return for which he withdrew a case against police for false arrest, false imprisonment, assault and malicious prosecution. Later fined $75 for the assault of his wife’s boyfriend and $500 for the slander of Christiansen, Robinson emerged from grave legal adversity with scarcely a scratch.

The outcome of the Trial case left the Museum Act looking alarmingly shaky. The fate of Western Australia’s maritime heritage now unfolded along slow-moving parallel paths. Robinson’s challenge to the constitutionality of the Museum Act took nearly a decade, becoming part of wrangling between the commonwealth and states over sovereignty of the territorial seas after 1973’s Seas and Submerged Lands Act. By the time Robinson’s case was finally heard before the High Court in September 1977, the court divided, but on the casting vote of Chief Justice Barwick upheld Robinson’s argument. Barwick rejected the museum’s claim that Robinson “had no greater interest than a weekend picnicker who happened to drop upon the wreck during his weekend leisure”; he was unconvinced that the act was “for the peace, order and good government of Western Australia”.

Success was bittersweet. Robinson was essentially outrun by the Fraser government’s promulgation of the pioneering Historic Shipwrecks Act – comprehensive legislation extended to all wrecks older than 75 years between the low tide mark and the edge of the continental shelf. Australia’s sophisticated and robust maritime heritage protections, consolidated four years ago in the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act which extended protections to aircraft, are now envied around the world. Here’s an irony: probably no single influence was as significant as Robinson’s chaotic depredations.

Robinson now sought different treasure. With Lyn and his son Geoffrey, he quit Perth for Roebourne and then Karratha, where he profited from the opening of the Pilbara, establishing an underwater survey business and opening a 1000 square metre showroom for sporting and marine gear. He became a “local identity” but on February 11, 1978, 18-year-old Geoffrey was killed in a freak accident involving an out-of-control drag racing car. His headstone reads: Post tot naufragia portum (“After so many shipwrecks a port”). Robinson could find no such solace. “He went downhill fast after that,” Heenan agrees.

Lack of attention smarted: he self-published a self-mythologising memoir, In Australia, Treasure Is Not for the Finder (1980). But nor did attention prove welcome: he was prosecuted under the new Historic Shipwrecks Act for trading in recovered coins. He began giving erratic interviews, boasting of wealth, complaining of pennilessness, hinting of great discoveries, planning further searches, including for Lasseter’s Reef. Worst, his relationship disintegrated and Lyn fled him for Melbourne. His new girlfriend, Patricia Green, almost 30 years his junior, was a typist he had hired to type the script for a biopic.

The end was then almost impossibly murky. Robinson and Green were charged with the theft of explosives, then with conspiring with two others to murder Lyn. By this stage, Green was pregnant with his child. For six weeks, while on bail, Robinson vanished, claiming to be gun-running, only to be captured at gunpoint in Larrimah in the Northern Territory in June 1982. The committal hearing sprawled for almost two months, with a week’s delay for the birth of the couple’s son. Robinson languished for months in Long Bay awaiting trial.

The evidence, again, was flimsy. “There was always a sense of huge overkill about the various state police forces’ treatment and view of him,” says novelist Robert Drewe, who first encountered Robinson at the West Australian in the 1960s and who covered the trial for The Bulletin. “Focusing on a single bad boy in these episodes was simply wrong.” A jury seemed likely to agree: they acquitted Green on November 2, 1983, and the next day were bound to acquit Robinson. But that morning Robinson was reportedly found hanged in his cell. The coroner’s verdict was suicide.

Robinson continues to divide. At the time of his death, Heenan was acting for Robinson in seeking compensation for his prior explorations. Drewe’s 1986 novel Fortune introduces charismatic diver Don Spargo, a thinly veiled Robinson, who “seemed to see himself as an amalgam of Jacques Cousteau, Columbus and Dreyfus” and was “not unhappy with the idea of himself as a buccaneer or bushranger”. It concludes with Spargo’s murder in jail to prevent his “winning the four million dollars of High Court settlement”, reflecting some lurking suspicions among those left behind. Former diving partner Rex Woodmore pays Robinson homage with a website, oztreasure; a Facebook page describes him as “a sub-aquatic Ned Kelly”.

But the cause of maritime heritage, and the WA Museum’s pride as a leader in the field, resulting in the spinning off of Fremantle’s Maritime Museum and the Shipwreck Museum, almost required Robinson to be demonised – he represented the bad old days of lawlessness, which were paradoxically also days of discovery, before the modern age of legislated enlightenment and bureaucratic tidiness. As Graeme Henderson rose to the eminence of director of the Maritime Museum, his father published Phantoms of the Tryall (1992), denouncing Robinson as “a powerful and cunning psychopath”. Peter Du Cane produced a dramatised documentary, The Gelignite Buccaneer (1995), which ignored Robinson’s role in the discovery of the Trial altogether.

But so did the WA government. Its Select Committee on Ancient Shipwrecks deliberated for more than two years on “the persons who were the primary discoverers of the ancient shipwrecks off the Western Australian coast… and to establish if there were any secondary discoverers who might have rights of recognition”. In August 1994, it deemed Robinson neither, despite his having instigated the dive that located the Gilt Dragon and the expedition that located the Trial, on grounds he “fell far short of the standard of public spirit and co-operation shown by other discoverers whom the committee wishes to recognise”.

But even Jeremy Green, who established the museum’s department of maritime archaeology and recently retired after half a century, thinks the stance absurd: “I think that committee made a number of flawed decisions. They had their favourite people whispering in their ears who should be in and who should be left out. That was partly because he [Robinson] was such a reprobate. But that doesn’t matter, he was still a primary finder. I thought that was unfair.”

Shipwrecks, of course, excite surprising passion, mixtures as they are of time capsule (Shackleton’s Endurance), totem (Cook’s Endeavour) and tomb (HMAS Sydney II). Conflict over their treatment might even be thought analogous to white settlement. What was Australia to its European discoverers? Did it have a heritage worth preserving, or was it simply south sea treasure awaiting acquisitive finders? The countrymen of the crew of the Trial experienced few pangs about blowing the land open; Juukan Gorge suggests that the mindset persists. Alan Robinson might be a more contemporary figure than has been allowed.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout