Novelist Alex Miller searches for his friend and mentor, Max Blatt

Novelist Alex Miller had almost given up on writing a book about his late friend and mentor, a survivor of Nazism. Enter journalist Fiona Harari…

I wasn’t looking for a story when I hurried into Alex Miller’s talk at the 2018 Perth Festival Writers’ Week, pleased to have grabbed one of the last of several hundred seats in the capacity audience. But unexpected endings can come from inconspicuous beginnings. And this one I almost missed.

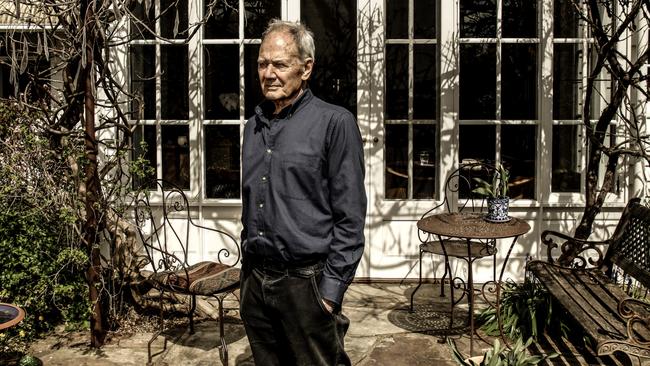

A two-time winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award, Miller was discussing his new book, The Passage of Love, a fictionalised account of his ascendancy as a writer. Then 81, on stage he was a striking presence, frank, expansive, moving his strong hands around to demonstrate a point, seemingly unguarded as he read at length from his book and entertained the audience with answers that meandered far from the questions he was asked.

But it was when he spoke of one man that my heart lurched. For years, he said, he had been trying to write a non-fictional account of his late great friend Max Blatt, a victim of Nazism who had been the inspiration for much of his work. He had spent ages researching Blatt’s life, but when Miller’s wife Stephanie read the manuscript she had declared that it contained two stories: her husband’s – which resulted in The Passage of Love – and Blatt’s, which she suggested ought to be another book.

Miller, however, expressed doubts during his talk that he could complete this latter volume of non-fiction. Blatt had been keenly important to his life. With great faith in Miller’s ability, he had urged him, from the earliest days of his career, to write about what he loved. He was the subject of Miller’s first published work, the short story Comrade Pawel, and everything he had penned since had been with the hope that his late mentor would have admired it. Yet now his research had stalled and he was ready to give up. As he would write later: “It felt as if the trail I’d been following for the previous five years had led me to the edge of a cliff, and I was standing there gazing into the void.”

Of all Miller said that morning, four words reverberated. A victim of Nazism. I was about to discuss my own work, We Are Here, the stories of 18 of Australia’s oldest Holocaust survivors. In the course of my exhaustive historical research for that book I had deepened my conviction about the importance of telling survivors’ stories. Now Miller was about to give up on one of them.

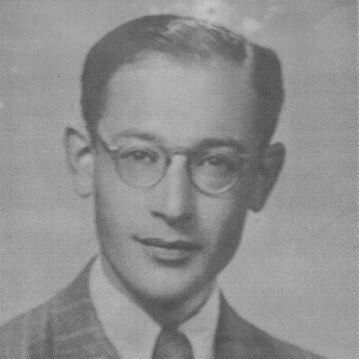

As the session continued, I Googled “Max Blatt”. Before I could conjure this man who still filled Miller’s heart, I clicked on a National Archives of Australia link for Mozes Blatt, and my phone screen was filled with a tight, handwritten naturalisation application from 1952. A search on the US Holocaust Memorial Museum website revealed more information. Within minutes I had an image of a diminutive man with black hair and brown eyes, who had been born in Poland at the turn of the 20th century, moved to Germany and then back to Poland before arriving in Shanghai in 1941. He had lived out the war there, working as a pharmacy assistant, marrying Ruth Heinrichsdorf in 1946 and arriving in Melbourne the following year, where he lived in the suburbs and was a tailor and then a machinist. Although the spelling of his name varied – Moses/Mozes, Blat/Blatt – there was a consistency to his origins and his path to Australia. Could this be Miller’s Blatt?

At the end of the talk I introduced myself to Miller and offered to list other avenues for research. We spoke a couple of times that day and when the weekend ended, armed with Blatt’s name, place and date of birth (the person whose documents I had found online was indeed him), I said I would try to find out more. I had a few spare hours on Monday morning. Why not?

As we flew back to our homes on the other side of the country, the journalist in awe of the formidable novelist, neither of us had any idea we were embarking on a collaboration that would span years and continents, culminating in a trip that Miller would later describe as “the most important journey of my life”. And all of it largely down to a random corner of the internet.

The next morning, after a few hours online, a more detailed impression of Blatt emerged, proof of how much of a lifetime unknown, obscured or lost to history can sometimes be unlocked remotely. Born in Lubaczow, Poland, in 1907, he later lived in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland) with his father Josef and mother Lea. He had a younger sister, Sarah, who was deported to Auschwitz in March 1943 and died upon arrival.

Some time before the start of 1940, Blatt travelled to Lithuania, where he was listed on February 4 as a refugee. A year later he arrived in Kobe, Japan, and by the end of 1941 he was in Shanghai, where he remained before arriving in Australia with his wife Ruth in January 1947.

It was a detailed timeline for a few hours’ effort but it was the shadow of Blatt’s family that was so evocative. What had become of them? The website of Yad Vashem, the world Holocaust remembrance centre in Jerusalem, held some information about the fate of his parents and sister, all of whom were registered as having died during the Holocaust. The details were included in testimonies submitted in 1984 by Martin Blatt – who listed himself as the son of Josef and Lea.

So did Blatt also have a brother? And was he still alive? Googling “Martin Blatt” went nowhere. Then I noticed a second name on those decades- old testimonies: Liat Shoham. At the end of my long email to Miller detailing the morning’s finds, I wrote: “On a whim, I’ve just done a search for Liat Shoham… On a website about Jews from Lubaczow, I found this appeal (date unknown): LANDESMANN FAMILY: Last known family member from or in Lubaczow. My uncle Moses (Max) Blatt was born in Lubaczow on Feb 10th 1907. His mother Lea Blatt nee Landesmann was born in Sienawa, but was married and lived in Wroclaw (then Breslau, Germany). She went to Poland to give birth to her children, in order to make them Polish citizens. Why did she come to Lubaczow in 1907? We think she had a married sister there and hope to find out more about his branch of the Landesmann family from Sienawa/Lubaczow. Contact Liat Shoham…”

Was this Max’s niece, on the other side of the world, also searching for him?

Miller emailed back the following morning. “I was caught off-guard by the news that Max’s sister was taken to Auschwitz and was murdered there the same day,” he wrote. “It was a strong shock that went through my system and I sat here for a long time staring at your message. Why did it affect me like this? I didn’t know her, but I did know her through my love of her brother Max and my lifelong – since the age of 21 – debt to him for his generous friendship.”

They had met in the late 1950s. Miller’s first wife Anne had befriended her high-school German teacher Ruth and over many visits to their Caulfield home Miller developed a deep bond with Ruth’s husband, Max Blatt. Through their conversations and his own research, Miller learnt much about Blatt’s adulthood. Born more than 30 years before the start of World War II, in his teens he had been a member of the Communist Youth Association of Germany, eventually joining the resistance group Neu Beginnen – an anti-fascist group whose membership would be decimated by the Nazis by 1936 – and becoming the group’s leader in Warsaw. Later, over many weeks, he was tortured by the Gestapo. Miraculously he lived, although the emotional damage lingered for the rest of his life. As Miller would subsequently write: “I met him after the worst had befallen him.”

Like too many who survived that war, Blatt lived on with a sense of futility. “In his own eyes,” said Miller, “he was a failure and had achieved nothing.” His dreams of overturning fascism in favour of a socialist Germany had been shattered, most of his family had been murdered, and he forged an alternative life in which he rarely discussed his past. He took on mostly menial jobs, retired in his early 60s and died, aged 74, in 1981. He and Ruth, who died in 2001, had no children.

Almost 30 years his senior, Blatt had been Miller’s must trusted confidant, a man whose considered silences left a deep impression. Yet he knew almost nothing about his friend’s formative years, and those who had loved him first.

Although it seemed to me like weeks at the time, it was only two days after the discovery of that genealogical website that Miller emailed Liat Shoham. “Max was my dearest friend for many years until his death… the greatest influence on my life and the direction of my writing… I want to commemorate our friendship and to celebrate his life.” He outlined what he knew about Max, adding: “It occurs to me also that you may know things about Max that would be of great interest to me.”

The email address on the website was care of Eva Floersheim, a genealogist who had been Shoham’s neighbour in Israel before moving back to her native Norway, from where she replied to Miller within hours. “It moves me to hear from you and read about your project,” she wrote. “Uncle Max has been a subject we have talked about many times. Liat is the daughter of Martin Blatt, the brother of Max Blatt.”

There were many emails over the following days, sometimes to Floersheim and Shoham and sometimes to me. Miller’s correspondence was a gift; stirring, always beautifully composed. “Being in contact with a relative of Max’s is deeply important to me and very moving,” he wrote a few days later. “There have been many times when I’ve almost given up on this book about him as the possibility of reconstructing his past seemed beyond me. But something made me go on. My wife tells me I’ve been talking and even trying for the past 30 years to write a book about him.”

There were more extraordinary discoveries, not least the fact that in The Passage of Love, Miller had bestowed the names Martin and Birte on the characters of Blatt and his wife, only to now discover that Blatt’s four siblings had included a brother, Martin, and a sister, Berta.

A week after the discovery of Shoham’s contact details, at my urging, Miller phoned her and they spoke at length. “You reminded me so strongly of Max,” he wrote later, in one of countless four-way emails over many months between him in Castlemaine, Victoria, me in Sydney, Shoham in Israel and Floersheim in Norway. “It was very beautiful and also moving. I could hear his voice and his values, which you and I both seem to share, in everything you said.” Miller planned to travel to Israel later in the year. He pencilled in October, a pleasant season for travel, and soon Floersheim, whose internet notice had started this unlikely chain, wrote that she would travel from Norway to be there too.

Miller and I had often remarked, since we had met at the start of the year, about the serendipity of that presumably recently placed notice. More recently I had wondered aloud about other people who might have responded to it. So in a later email exchange Miller asked about that notice. Floersheim replied that she had set up the page in the late 1990s. Me: “Amazing! You placed that information on the website 15-20 years ago. What were the chances of Liat and Alex finding one another through that one notice? Almost no chance, you’d have to say. And yet they did. Eva, did anyone else ever answer your notice about Max?” Nine minutes later, she replied: “No, nobody else answered.”

Two weeks later I flew to Israel.

Liat Shoham is a warm and hospitable woman, diminutive like her uncle, and when she opened the door to her kitchen in rural Israel on a vivid day in October 2018 I saw a table almost overflowing with homemade cakes and coffee. Born in 1951, she had been living on this small dairy farm for more than 40 years, but since the death of her husband Naftali 10 years earlier she had lived largely alone, with a pecan tree in the front garden and behind it cows huddling in the milking shed.

As her widowhood progressed she became increasingly bereft and lost. Then an author from Australia contacted her about the extraordinary legacy her late, beloved uncle had bestowed upon his work. Now she stood in her kitchen with a small travelling party on that sunny October day for a gathering that was not so much a reunion as a fact-finding mission/celebration. Far from lost and bereft, she was happily overwhelmed. “It not only brought Max back to my life,” she said, “it brought me back to life. All of a sudden there was a meaning.” And she beamed.

She is a gentle woman, with short white hair and glasses, and a deep sense of family. After her father Martin was detained in Europe for several days by the Gestapo, who had mistaken him for his older, activist brother Max, he was smuggled out of the country and into pre-Israel Palestine, where he remained for the rest of his life. His entire family was killed in the Holocaust, except for his eldest sibling, whom Shoham first met in 1963 when he travelled from Melbourne to Israel for her brother’s barmitzvah. “Max was an extraordinary person,” she told me. “He had such wisdom. For me he represented all the family that was lost.” But he was also weighed down by his own history, shattered from being tortured and all he had lost; our research also revealed a first wife, Hannah, who is thought to have been murdered by the Nazis while pregnant. “Max was totally broken after the war. He couldn’t do anything. You could see it in his eyes.” He tried many jobs in Australia, including teaching, but the weariness that shrouded his post-war self also trampled his employment prospects. “He didn’t succeed because he was too slow. And then the education department said, ‘You’re too slow; you couldn’t teach the children. You won’t finish anything.’”

As a schoolgirl, Shoham had spent a year in Melbourne living with her aunt and uncle. Later, in the year of his death, and after so many years of silence, her uncle told her of his plans to write about his life. “He said, ‘I have an author friend and he will help me,’” she remembered. “But Alex didn’t know about it because a few months later he [Blatt] passed away and he didn’t have a chance to tell him about this book.”

For Alex Miller, Blatt had been “my ideal of humanity, a man cultivated, wise and generous, a man who believed in me, a man who had been to the mind’s limits and returned, broken but not cowed. And in the deepest recesses of my soul,” he would write in his eventual tribute to his mentor, “I continued to believe in the novelist he had seen in me. His opinion meant everything to me.”

Yet there had also been a late silence in their friendship, and one, it would seem, that continued to haunt Miller. Although they had been best friends, the author had not seen Blatt in the two years leading up to his death in October 1981. “When Ruth asked me why I didn’t go to his funeral,” Miller wrote in an email in March 2018, “I told her that Max and I had an understanding about such things. She scoffed at this, but I still believe it to be true. He had no time for ritual of any kind. Our farewell is still being played out.”

Even the best friendship can be tinged with regret. In our many conversations, Miller never quite expressed why he had not seen Blatt in his final two years. And then he wrote this much later: “My three failed attempts at writing a novel had drained my self-belief. I had not persisted but had been too ashamed to tell Max. It had been easier, and more cowardly, to stay out of his way.” And then he was gone, and almost ever since, it seemed, Miller had tried, and failed, to write a book about him. Until now.

So what would Blatt, who 40 years ago told his niece that Miller would write his story, think of the result? “He dealt with guilt and grief,” says Miller, remembering his friend who saved one sibling but lost the rest of his family, and who died not knowing what had happened to them. “I think,” he says, “he would weep.”

Max by Alex Miller (Allen & Unwin, $29.99), out Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout