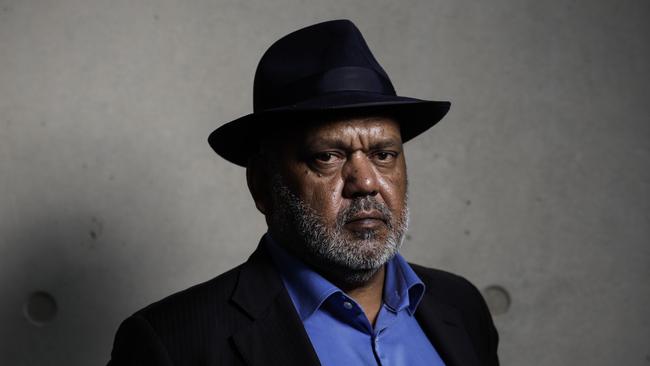

‘Not a day goes past when I do not think about my father’

Noel Pearson was 23 when he lost his dad. And not a day goes by when he doesn’t wonder, what would he make of me now?

I blame my father. Or at least I try to. I don’t remember if he told me directly or if he was making a rhetorical statement to the general audience of our household about some incontrovertible truth, whether gained from his grasp of Lutheran theology or having read it in one of the religious texts that sat in the small plyboard bookcase he made to keep the little literature we owned (as much as you can really own hand-me-down books from the local mission staff): life’s purpose is to serve God and serve your fellow man.

This injunction became my life’s purpose. It has never left me since I first heard it as my father’s boy. I’ve blamed my father for neglecting myself. Like I thought he neglected himself. The truth is that I’ve never neglected myself; it is just that I’ve felt my father’s gentle admonition every time I don’t. He was not a stern man. He was no imposing figure of rectitude or Mosaic eminence in my life. It wasn’t like that at all. He was humble, and he valued putting yourself second to others. He thought humility was something to learn in life, the first kind of wisdom. Real virtue in his lights was to turn the other cheek.

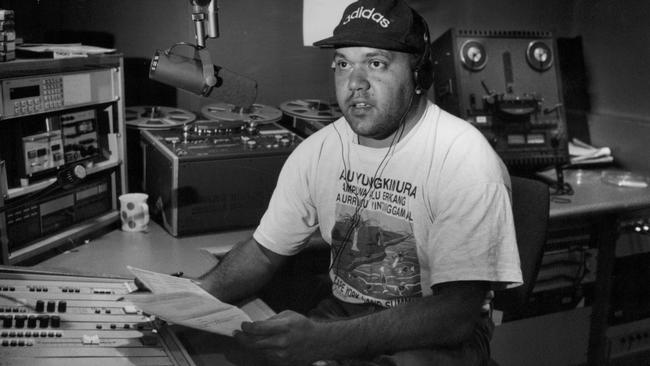

He died just as I was making my debut into public life. And an auspicious start it was too: elected councillor of the Hope Vale Community council [north of Cooktown, far north Queensland] in early 1988, the beginning of a two-year adjournment of my law studies at Sydney University, when I returned to my home town. By August, on the day of my sister’s 21st birthday and in my 23rd year, he lay dead on the kitchen floor of our house, the victim of a massive heart attack that had been stalking him for years by the time he died aged 62.

He often told me of the fateful day how as a grown man he had cried like a child when he received news of his mother’s death. Aged 62. Now he was dead on the floor of our old, creaking fibro house which he built. And I could not revive him. I tried to breathe life back into him and had struck blows onto his barrel chest, to no avail. My brother and sister were out of their wits, howling, and my two uncles who had rushed down to help me were calling his name in that frantic kitchen as if they were searching for my father lost in a pitch darkness (nguul manhthiwi). But it was a bright morning. Sister Kay arrived from the clinic, but his day, and mine, had come.

Why do I speak these things about my father? I do so not to convince the world of his worth and his goodness. I have no need to do that. That this man was unremarkable to the world and that his early death was a small tragedy for a small family in a small village – like so many others – matters nothing to anyone else. He was my world, that is all.

It was his intuition about what I should do with my life; that is why I mention him. If there was fault in it, and whether or not a good intuition may have played out in a poor life, then the fault was not his, of course. Every folly has been my own. Every last damned one of them.

It’s my 56th year, and I’m still playing hard, butI can’t avoid glancing up at the scoreline of my life’s work, the tackles missed, the metres gained, the penalties and yellow cards like confetti, the fights, as often with my team standing behind the goalposts after conceding another try as with the opposition, the confrontations with the referees and sledging of opponents, the ever-accumulating injuries of a breaking body. The clock runs down faster when you’re on the wrong side of the summit. One of our elders from the old folks’ home, Bedford, who has since died, once one of the mission’s truck drivers so he knew well what he was talking about, said that old age is when you’re going downhill and you’re pumping the brakes to no avail (wawu murrgarra), your truck hurtling ever faster towards an ignominious end. Old man Bedford’s joke circles the community and gives everyone a laugh and reminds us how much we love him.

The game’s not over, but there’s no escaping I’m in the last stretch of my prime. I’m haunted by thoughts, not of failure but of falling far short of the ambitions I hold for my people. I can plainly see trees we planted over 30 years of our agenda – it is the forest view that depresses me. The challenge of scale still eludes us. The kind of scale that speaks to structures that impede us as a people, and not just individuals, in achieving better lives. The scale that comes with government and executive power rather than just activism.

I think about Paul Keating. He was 52 when the main of his life’s work ended with the 1996 federal election. His life’s work was leadership in politics, and the scope and scale of his achievements plain, obvious, colossal. Like a Zeus, he drove the long lever between the plates of the continent and effected tectonic change. On enemies, Keating gives me Jack Lang’s old advice: “You’re never any good until you’ve gathered a good collection of enemies.” For one who has garnered more than his fair share, there is solace if not always succour in this. He’s now 77, a year younger than Joe Biden and a better leader of the Labor Party than any of his successors, even today. Many, from both sides of the aisle, dream of being his next incarnation, but none has come close. These pretenders, he says, “have the lyrics, but they don’t have the music”.

My choices on the crossroads of my life’s work were not always right. I made too many mistakes. When I turned 23, I chose to serve my people. It was the right thing to do. At 33, I should have tried the political path to power inside the tent, but I hesitated. I did not yet possess the vantage of self-belief to see its viability, and the necessity I only now see in hindsight. I reached another juncture at 42, but by then I could never really commit to anything other than what I was doing. I had blinkers on my vision, and I thought we still could achieve the things we wanted without the diversions and mundanities of professional politics. Compared to the work I was doing, what does a politician do, for f..k’s sake?

By the time I became convinced I had no chance of achieving my mission outside the institutions of power, I was approaching 50 and there was no chance of getting in. The aperture to the fishbowl of Australian politics via the established political parties is small. It allows ingress to small fish early in their careers, but bars larger fish who have spent their rowing years on the outside. You either grow up on the inside or the outside. Only leading the Australian Council of Trade Unions has been a guaranteed path of grown fish from the outside to the inside, and only because of its structural integration with the Labor Party. The truth is, the projects we embarked upon needed the levers of power you don’t have when you’re an activist.

Since I turned 23, each passing year has been a journey towards becoming my father. My sense of this has become more acute as I count down to my 62nd year, when my journey will be complete. I don’t know if everyone or anyone feels like this over the trajectory of their lives. I have watched my evolution over these long years and seen the inexorable emergence of my father in my visage, my body and the personality and psychology roiling under the surface. Turning 62 – something that will happen to me in six years if the gods are willing – used to fill me with dread, given the common thread between myself, the grandmother I never met and my father. But now my near-complete transformation into the man I loved has become a beautiful thing and a thing of grace to me.

My father was 40 when I was born, the last boy and second-last child. For a long time I thought I would not have children myself and would instead invest my life in the children of our mission – and later on, I thought, in the wider world outside. But when I turned 40 I had a son, and the deep loneliness that sat in the middle of my soul since my old father died when I was 23 lifted.

I always talk about my old father, but at 62 he was not long-lived. The defining person in my life – my best friend and the man I would most emulate in the world – was gone after sharing my life for 23 years. And I’ve counted the milestones in the three decades since, thinking he would have been 70 when I turned 30, 90 when I turned 50, and wondered what we would have talked about. I remember my sadness when I realised at 47 that I had lived more of my life without him than with him.

My melancholy for my father has been a defining part of my life. Not a day goes past when I do not think of him and examine myself in the light of his life and his place in my life. My constant question to myself: what would my father think of what I have done or am thinking about doing? If I have any kindness, it is from him. If I have any devotion, it is from him. If I have any humility (and, yes, it is nowhere near his), it is because I am reminded of him. If I have any wisdom and goodness, it is because I try to be the son and man he would have wanted me to be. I am a more complex man than my simple father, and the life I have led exposed me to a larger world than his, but the inner core of my life is the life he showed me: love for our fellows, respect for our elders, honour for our people, humility in our sense of what we can make of our lives, but ever striving to do things properly and faithfully, thankfulness for our blessings and our duties to God.

I have a constant awareness of how I fall short of my old father’s goodness. To talk of his goodness is not to say he was more than an ordinary man striving to be good. I spent enough time with him to know his limitations and weaknesses. He was eccentric in a low-key way, a quality I came to admire and share since I was a young boy. He was neither bashful nor ashamed about what he believed and what he thought was the right thing to do. His courage was not ostentatious, but it would never be wanting.

I think by the time I came along my father had mellowed and worked out how he could be a good father. His parenting, modelled on his own parents’, the teachings of the mission and the culture of our people, was based on obedience and respect – so physical punishment with a belt or switch was part of the parenting style. Despite this, he was never cruel, and I long assumed that “spare the rod, spoil the child” was still a necessary part of parenting – until my son was born.

I followed my father everywhere. To work. To church. On trips away. To meetings. To Bible study in the evenings. When he worked in the garden, or visited the local farmer to buy cornseed to plant for our pigs – at these times, various of my older brothers would be present, and I would always be.

We developed a gentle friendship. How natural it was for him to rub my back when I sat reading at the kitchen table, and I would go into my mother and father’s room when they lay resting after church, to lie in the crook of his armpit while he and I read. I was 19 and attending university in Sydney, and I still napped next to my old father on a quiet Sunday. He was a jack-of-all-trades. My father instilled in me, as he did in all my siblings, the value of work, and in his own small way, of enterprise. Our beloved pigs represented his striving to supplement the meagre wage he earned as a butcher working for the mission. Given that $45 was the largest weekly wage packet I ever saw him open, he was always saving and had money in the bank to buy a replacement outboard motor, to buy a second-hand tinnie when truckloads of them arrived from Cairns Boat Hire and killed wooden boat building in our home town overnight. My father too built his own clinker boats, until he succumbed to the marvels of aluminium.

He bought two old Land Rovers and later an old trayback Toyota, all of which spent as much time with the hood up as they did on the road. He was the slowest driver in the mission, bar none. Possibly the world. And I would be riding shotgun, his constant companion. When the blue-tailed mullet season was on, like all the men, he had his new spears ready. I would be his skipper and we would drive to the McIvor River or Fullers in the early morning to hunt my most favourite fish, large, stunning silver and blue mullet, perched in groups under the edge of the mangroves in the shade in the incoming tide. My father was a dead shot with a spear.

I was a good tillerman, in the rivers and out at sea in the rough, learning from the old man how to handle the waves threatening to overwhelm our flatty. When quietly stalking the mangrove edge with our 9.5 horsepower Johnson, I would sometimes make a jerky mistake and rev when I should never have and he would lose balance and end up on his back in the boat in pain. And I would wait for him to recover, not moving, not saying a word.

I sometimes dream of meeting my father again, but it is not an untroubled dream. I fear we won’t know each other, because it has been so long, and how I have changed may not be what he had hoped for me.

Edited extract from Mission: Essays, Speeches and Ideas by Noel Pearson (Black Inc, $49.99), out November 30

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout