My life in tights at the Australian Ballet School

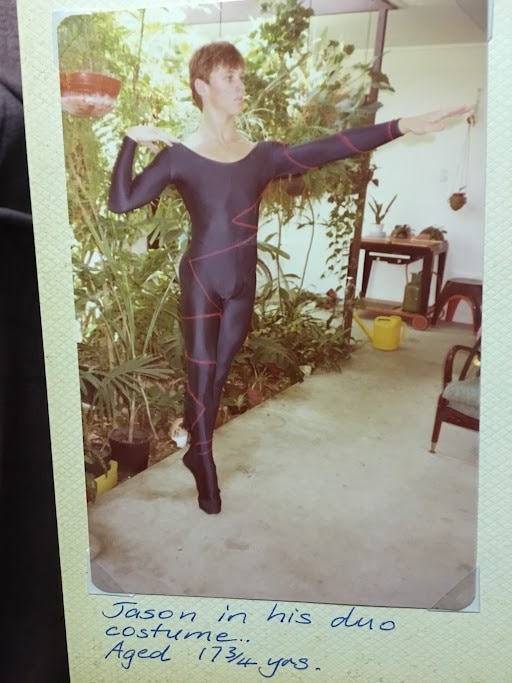

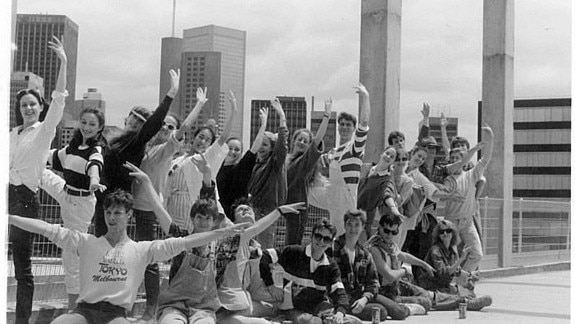

As a teen in the ’80s Jason Gagliardi performed ballet in Outback Queensland before heading, wide-eyed and innocent, to the big city. And he lived to tell the tale...

I knew that eventually I’d have to go shopping for a pair of proper ballet tights. What I hadn’t figured on was the attractive assistant at the dancewear store twirling an elaborate jockstrap around in front of a bunch of suburban ballet mums and their daughters, bellowing at me: “You’ll be needing one of these. What size are you? Medium … or small?”

“These” were supports – elastic contraptions designed to hoist the family jewels out of harm’s way as the male dancer plies, jettes, pirouettes and attempts other potentially nut-cracking manoeuvres. The support accounts for the lumpy bulge you will no doubt have noticed in the nether regions of male dancers. You may also have noticed that some boys are bigger than others … although it was not unknown for some to stuff their support with a sock or two.

Such were the initiation rites awaiting a boy bitten by the ballet bug in the back of beyond. I grew up in Townsville, North Queensland – a town in the grip of a youth crime epidemic these days, but an innocent enough place back then. I’d gotten into ballet on a lark and as a way to impress a girl. Donald, a school mate of mine, was keen on one good sort in Grade 10. I fancied another. As sophisticated men of Grade 11, we figured a sure-fire way to their hearts was to impress them with our graceful terpsichorean prowess. Unfortunately we couldn’t just talk the talk; we had to dance the dance. And so we signed up as extras for Cinderella, the annual gala performance by the North Queensland Ballet, which was now bolstered by a couple of ungainly galahs.

Even as extras, we had to take classes at the leading regional ballet school to gain some semblance of co-ordination and master the basic moves. The first few times we wore shorts. We learned how ballet class unfolded, beginning at the barre and progressing through a sequence of bends, twists, glides and stretches. Then moving to the centre and learning to string steps together.

Naturally, we were terrible. We fudged, fumbled and giggled our way through classes at first. But from those first faltering steps, I also felt the stirrings of something I couldn’t quite put my finger on: that quivering, queasy tingling that marks the start of an infatuation.

After a couple of classes, it was whispered in our ears that proper male dancers – danseurs, in fact – wore tights.

For a relatively normal suburban Australian boy, the idea of wearing tights was naturally confronting. It felt dangerous. Subversive. And likely to earn me some painful schoolyard taunting, if not a beating. At my high school the real men played rugby and cricket. Also-rans like me opted for soccer. The nerds and geeks fiddled about with computers or joined the chess club. Ballet was so far removed from anyone’s imagination that it had no real place on the totem pole. Basically, I was Billy Elliot.

There’s a good reason why dancers wear tights, of course: it’s to highlight the unadorned beauty of the human body and the purity of line that ballet requires. The clinging lycra prevents attempts to hide faulty technique from the hawk-like gaze of the ballet master or mistress.

As I pulled on my first pair in the dance studio’s little-used male changing room, I was trembling with trepidation. But like some lithe Narcissus gazing into his pond, I slowly raised my eyes to the full-length mirror and noticed that my legs looked rather fetching. It turned out that I’d been blessed with the right kind of body for ballet: flexible hips, long legs, tapered torso. I had fairly flat feet but exceptionally loose ankles, which made my toes look freakishly pointed – another highly prized asset by ballet’s strange standards.

Heading to class with my bag full of ballet gear felt dangerously thrilling. This was the mid-’80s in Australia’s far north, where real men perched in pubs in stubbies and long socks, and everyone owned two pairs of thongs (your day-to-day pair and your dress thongs). A hard, parched place where the highest rate of skin cancer in the world aged people before their time. Townsville was a rough army town with a thriving yobbo culture and an undercurrent of violence simmering beneath the surface. A town where the local weekly free-sheet once splashed with the headline: “Poofs in the Park”.

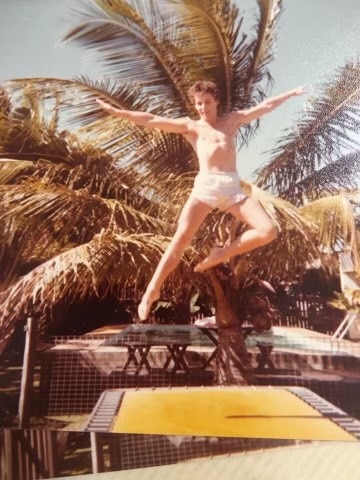

I took to ballet like a swan to water. I became obsessed, prowling in bookstores for ballet books and searching video stores for films of the Royal Ballet, American Ballet Theatre, New York City Ballet and other legendary companies. My technique began to improve as I attended class every day after school. Seeing me practising my leaps in the backyard, our neighbours must have thought I was nuts.

My twin heroes were Rudolf Nureyev, a coruscating genius who would ultimately meet a tragic end with AIDS, and Mikhail Baryshnikov, the other Soviet defector, technically Nureyev’s superior and captured at the height of his powers in The Turning Point, a movie I watched until the video tape wore out. Much to my parents’ displeasure, I turned down the chance to study law at the University of Queensland to take up one of the dozen or so spots handed out to boys each year at the Australian Ballet School.

Donald and I didn’t win rave reviews for our clumsy waltzing and precarious presages in Cinderella. But we did get to enjoy a fumble – or “full crumpet” as it somehow became known – with our ballerina crushes in the back of the bus as the show went on the road on weekends to a succession of country towns. I was also offered a year’s paid traineeship with the North Queensland Ballet, which was in the throes of becoming a proper professional outfit known as Dance North. (These days, it sports the trendier moniker dancenorth and enjoys a reputation as one of Australia’s most innovative contemporary dance troupes).

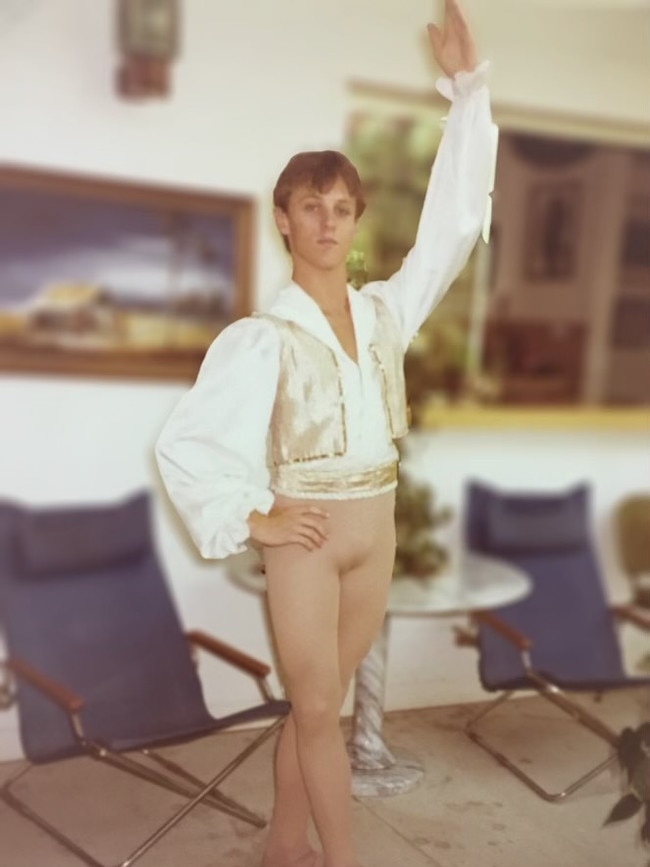

Part of the funding came from the Queensland Arts Council, which meant we had to embark on a succession of tours to some of the most remote outback towns and rugged mining outposts imaginable. I was teamed up with Trevor, fresh from a stint with Sydney Dance Company, floppy-fringed, acid-tongued and enormously doe-eyed, possibly the campest thing ever to flounce out of Oxford Street, and Susie, a small but perfectly formed ballerina who was sex on well-defined legs.

There were bigger performances with the full company but the Arts Council odysseys account for my most vivid memories. We would roll into town, locate its school, set up the stage and get our costumes ready. Then we’d slap on some pancake and ham it up in front of the bemused and wide-eyed students. We would repeat the whole process one or two more times in different towns before going home.

In places like Mt Isa, Richmond, Hughenden, Cloncurry, Longreach, Winton, Blackall, Barcaldine, Charters Towers and Ravenswood, there wasn’t a great deal to do at night. You drank, or you slept. So we would invariably find ourselves in some pub where the locals congregated in sweaty singlets with sailor tattoos. (The men didn’t dress up either!) They would ogle Susie over their pots of XXXX beer as she teased them with her pretzel limbs, treating the bar as a barre, while shooting dirty looks at Trevor and I, arty outsiders in our trendy clobber and doubtless in need of a good thumping.

This was like catnip for Trevor. The filthier the looks became, the louder the mutters, the more outrageously he’d pout and bat his big eyes. On more than one occasion we had to hightail it out of town, sprinting for our battered van as the lynch mob formed. This was pre-Priscilla, but the pointe shoe certainly fit.

The Australian Ballet School was another adventure, though not necessarily from the Boys’ Own oeuvre. In my day, it hadn’t yet taken up residence beside the Yarra River in the posh Performing Arts Centre; rather, it was accommodated in a converted tyre factory on Melbourne’s Mount Alexander Road. I was lodged in a mouldy ground-floor flat in North Melbourne, near the Queen Victoria Market. My flatmates were Brett, a second-year student beset by worries about his acne, thunder thighs and child-bearing hips (his descriptions), and Mal, a talented fellow first-year student from the outskirts of Adelaide.

The School, as we called it, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year, attracted a certain species of ageing homosexual who couldn’t resist the legion of young men in tights. I suppose they fancied themselves as patrons of the arts; patrons of the arse, we joked.

My circumstances were fairly exigent in those days but I eschewed the importuning of these “Uncle Monty” types and managed to make ends meet working in a succession of Melbourne’s grand old hotels at night, roaming the corridors doing turn-downs, pilfering wine, cheese, chocolate and the odd bathrobe, often managing to barge in on people mid-bonk. As I was still a virgin at the ripe old age of 17, this turned out to be a handy crash course in sex education. One of the most active patrons was a gravel-voiced old luvvie named Maximilian, Max for short, maximally interested in the contents of one’s boxer shorts. Maxmoid, we called him, if we called him at all. Why, I have no idea.

He sometimes saw fit to donate his swanky South Yarra pied-à-terre to the school’s students for parties. I remember my first. A callow lad straight off the bus from Townsville (literally – it was a hellish, cramp-inducing three-day trip that nearly ended my ballet career before it had begun), still settling into the big city, I overindulged in spirits and became tired and emotional. In those days I was a pretty young thing, and in between fending off the unsolicited ministrations of Max I managed to capture the attention of a third-year man-eater named Cherry. It was a nailed-on dead-set cert, just a matter of turning up. Instead I burst into tears and demanded to be taken home. Brett was only too happy to oblige and tucked me into bed, listening to my sobbing litany of suburban dislocation and teenage angst. Our briefly flowering friendship was to end when, some hours later, I thickly awoke to find him trying to wrestle my trousers down.

It wasn’t to be my last brush with Brett. He became a bit obsessed with me, and I took to spending as little time in the flat as possible. I’d loiter after class, practising my spins and leaps. I’d dawdle at the hotel, drawing out my shifts as long as I could. Things finally came to a head about eight months into term, when Mal and I heard a faint rustling in our cupboard. Smelling a rat, I put a finger to my lips and crept out of bed. I put my ear against the door and discerned a muffled groan.

I grabbed Mal’s cricket bat and flung the door back. There, with a stricken rictus, crouched Brett. I screamed. He fled. A week later, Mal and I moved out. We moved in with Joanne, a tall, willowy blonde from my year to whom I’d taken a fancy. Later, we’d marry. Later still, divorce.

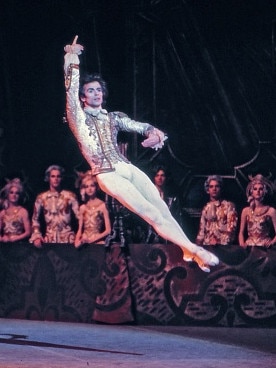

I’d study diligently and make good progress but somehow my ballet infatuation was fading. I’d have the opportunity to see the stars of The Australian Ballet up close and personal, as an extra in performances of Swan Lake, Giselle and Don Quixote. I’d meet Sir Robert Helpmann, impossibly frail and literally on his last legs. I’d witness my favourite teacher and one of the best danseurs of his day, Kelvin Coe, wither away from AIDS as it cut its swathe through the arts. And I’d win the favour of Maina Gielgud (or “Mainly Feelgood”, as we called her), the company’s artistic director and niece of uber-thespian Sir John. After I announced my intention to hang up my tights, passion spent and beset by niggling injuries, she’d pen me a lovely letter urging me to reconsider.

After battling a series of stress fractures then a hip injury which required unpleasant sessions with a Swedish masseur with huge vice-like hands, I came good in time for our Second Year end-of-year performance in Melbourne’s swanky arts centre. On the bill was a modern thing loosely inspired by couch potato Norm of “Life. Be In It”, a series of TV ads of the time exhorting viewers to adopt a healthier lifestyle. I was a circus strongman, upstaged by some dancing vegetables. The main attraction was a selection from The Nutcracker, classic festive season fare. Apart from jumping around in the corps de ballet I was cast in the Arabian pas de deux with Rachel, who I held in a kind of awed regard. A dead ringer for the singer Sade and not one to suffer fools, she was streets ahead of me in technique and maturity.

Terrifyingly, the piece began with me having to walk the full length of the stage balancing her above my head with one hand as she lay back in a split. Even scarier, I was clad in billowing harem pants, shirtless, with a little Arabian hat. First night, it went off without a hitch. Night two, as I lifted Rachel above my head, my hat got knocked down and almost over my face, precipitating a walk of shame and a few muffled giggles from the audience. Unfortunately, a reviewer was present and my predicament did not escape his eagle eye. So my first and only review was a bad one. I guess my fez looked familiar.

Some time during second year, I would finally lose my virginity, fumbling beneath a fluffy doona to the crooned strains of Julio Iglesias (Joanne’s choice, not mine). I’d also have one more run-in with Max, in the toilets of an inner city shopping mall. Pants around my ankles, going about my business, I suddenly felt the hairs on the back of my neck rise and was seized by the conviction that I wasn’t alone. I raised my eyes and leering over the cubicle wall were the beady blue eyes and Father Christmas eyebrows of Max. A grimace of recognition swept over his features and, no doubt, my own. I leaped from my porcelain perch, arse unwiped, and burst from the stall like a racehorse erupting from the Melbourne Cup gates. As I threw open the bathroom door, grabbing at my pants, the last thing I heard was a stupendous crash and an anguished moan from Max.

Two months later, I found myself in Brisbane where my family now resided, ballet bug cured and wondering what the hell to do with my life. b

Footnote: After a short, lycra-clad diversion into competitive aerobics, the writer found himself employed at the Logan City Express, a weekly freesheet on the southern outskirts of Brisbane, covering scoops like the Kingston toxic ooze scandal. A new passion – journalism – beckoned.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout