My ‘absolutely legendary’ lover: John le Carré’s secret mistress comes in from the cold

John le Carré conducted their clandestine affair like a spy operation from one of his novels. Now his ex-mistress is spilling the beans — and she doesn’t give a damn about the consequences.

She is happy to call it an affair, although she prefers “love affair”. Nor does she mind my calling her John le Carré’s “mistress”. This afternoon it is, after all, the relevant job on her CV. Suleika Dawson (not her real name) is sitting in the grand bar of a central London hotel to debrief me on her complicated and paradoxical lover, the distinguished spy writer who came out of the cold and into her bed. She has quite a story to tell – sexy, funny, revealing, but also fractious, punishing, secretive – and it stars quite a hero or, you might conclude, antihero.

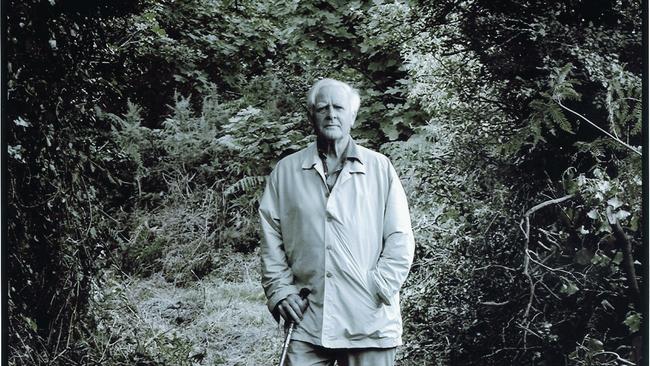

She and David Cornwell (the former MI5 and MI6 officer’s real name) were together for 30 months, split into two missions: two years between the summers of 1983 and 1985, and then, 14 years later, for six months in 1999. “But that was massive for him,” Dawson says. “The only people he had longer relationships with were his two wives.” Towards the end of her candid new memoir, The Secret Heart, she writes competitively: “If you were to calculate the combined time David spent with all his ‘other women’ it still wouldn’t amount to as long as we had together. Not even close.”

Apart from its title, The Secret Heart contains barely a cliché, so I apologise for asking whether he was the love of her life. “I think you’d have to ask me when I’ve had my life to make a fair assessment,” she says. “I don’t think I’m flattering myself to say I was genuinely the love of his. I think it just worked between the two of us. I don’t think he expected anything to work that well in his life. I don’t think he was very hopeful of finding anyone who really ticked all the boxes for him and clicked with him. And then it happened.”

The sex was, apparently, extraordinary and on the page she relates it in extraordinary detail, some of it not for repetition here. She describes their first bedding as the “sex that only the hero and heroine can have; sex for the cameras, sex for the gods”. Later congress may be quasi-spiritual; one session she regards as “a requiem” for a previous Cornwell mistress who died. Other times, it is not so spiritual, like the day he “drove into me like a ploughshare”. We learn that there was a “pleasing amount” to Cornwell and that his testicles could withstand her playful application of ice cubes. They would have sex three or four times in a day. His “powers of recovery” were “prodigious”. Cornwell himself professed himself amazed at the “amount of seminal fluid” she induced. Even second time around, when he is nearly 70, they enjoy “five hours of extraordinarily intense sex”. He was, she tells me with a smile, “absolutely legendary”.

Out of bed, Cornwell appears less effortlessly assured: arrogant but insecure, dismissive of others – other writers, friends and sometimes even her. This, we think, may be the anxiety of a writer who is also a “genre” novelist. Is Dawson arrogant? Aware of her own value, is how I would put it. She is not insecure, least of all about her desirability.

She chose Suleika Dawson as her nom de plume because, like Max Beerbohm’s heroine Zuleika Dobson, she was a femme fatale at Oxford University, she explains. When she met Cornwell she was a tall, willowy blonde who stood in contrast to Cornwell’s two wives and many mistresses, who tended to be dark and petite. Her legs, Cornwell said, went all the way to heaven. A boss warned that if she replaced her glasses with contact lenses he would not be “answerable” for his conduct. Today, in her early 60s, she is still formidably beautiful. Covid interrupted her hair-dyeing and it is now a light brown or, as she corrects me, “dark blonde”. Le Carré’s famous hero George Smiley had his heart broken by his beautiful runaway wife. Lady Ann was a blonde, Dawson observes.

She is certain Cornwell was faithful to her. That’s interesting, I say. The one thing a mistress can surely not assume is that a man who has cheated on one woman will not cheat on another. “Oh, I am. Always. With all of them. It’s never once crossed my mind that anybody would be unfaithful to me.”

She gives no sign of giving a damn about the propriety of publishing this kiss-and-tell less than two years after Cornwell’s death from pneumonia at the age of 89, but it has obvious justification as a profound character study of a great writer. She views herself in the tradition of women who have written about writers they have loved: Sheilah Graham on F. Scott Fitzgerald, Anaïs Nin on Henry Miller or Emma Tennant on Ted Hughes. Another is Susan Kennaway, wife of the writer James Kennaway, on her affair with Cornwell during his first marriage. Are they as frank as she is? “Carole Mallory’s on [Norman] Mailer was quite frank. She caught him trying on her stockings and suspenders one time. She included that.”

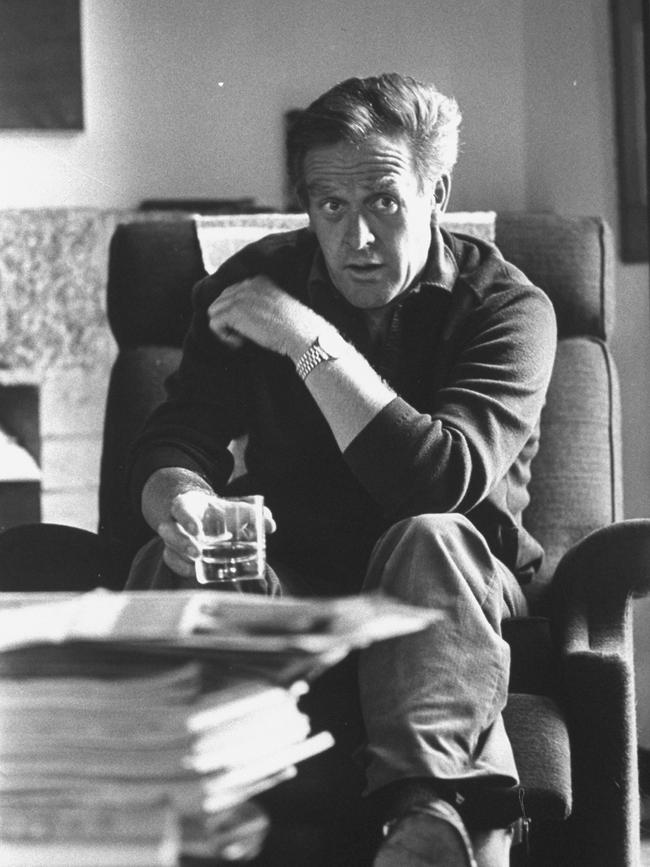

The affair with Cornwell almost started in September 1982. She was not long out of Oxford, living the life in London, abridging novels for the burgeoning audiobook business. Cornwell, commissioned to voice her redux of Smiley’s People, suddenly and silently materialised in the studio doorway having walked up seven flights rather than take the lift. She assumed he was going for a grand entrance. Years later, she learnt he suffered from claustrophobia. On day one he ignored her. The second day he invited her for lunch in a Soho trattoria, where he ordered champagne and everything on the menu. He lunched with intent, but she decided to decline any further approach and by the Eros statue in Piccadilly Circus he took the hint, kissed her “urgently” on the mouth and boarded a taxi.

How old was she then? She is reticent about her age, but he was 50. Since she and I were university contemporaries, she must have been 23 or 24. Today, I say, it would count as sexual harassment. “Oh, he’d be up there with Harvey Weinstein, I’m sure. I mean, no, he wouldn’t be up there with Harvey Weinstein, but he would have been pilloried in the #MeToo movement, let’s put it that way. It must be very boring being young today.”

He was not deterred. The following May his wife, Jane, rang on his behalf with some impossible suggestions about her adaptation of his next book, The Little Drummer Girl. Cornwell, she now sees, was preparing an alibi for his intended future calls to her number. Once the Drummer Girl recording was done, they dined (again ordering everything on the menu) and retired to his Hampstead flat where they had sex (everything on the menu) in his younger son’s bedroom. The affair was on. She gave up two lovers for him, she writes opulently.

She wanted for nothing. The all-you-can-order food was often abridged to carpet picnics of caviar and champagne, but the main course was sex. He love-bombed her with flowers, chocolates, jewellery and letters. Mini-breaks were choreographed by former spook “travel agents” he had worked with in the secret services (he quit MI6 in 1964 aged 33 following the success of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold). Their foreign assignations were paid for from a “reptile fund”, spook for an untraceable account for covert ops.

“A girl” (as he referred to Dawson to her face) could not ask for anything more, and nor did she, although sometimes she wished she had. When he offered to buy her a little cottage in Cornwall, where he had a home, and throw in driving lessons and a Citroën 2CV to get her there, she rejected his “Looney Tunes” offer. “I only wished I could have been enough of a tart to ask for a Chelsea flat and a Golf GTI instead,” she writes.

“He just had this extraordinary magnetism, and the more so when you’re the love of his life and he’s telling you you’re his last love and all the rest of it,” she insists. “It was an extraordinary beam of focus I got from him and he could just magic up wonderful experiences. It’s easy to say he had all the money to spend on the caviar and the champagne and hotels and all the rest of it, but it was nothing to do with that. There could have been much less money to spend. It was his internal magic – he could just present and wrap you up in it.”

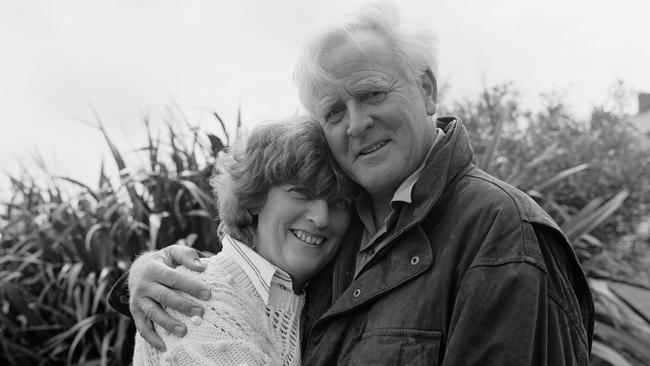

And what of Jane Cornwell, a former toiler at publisher Hodder & Stoughton? Jane was his mistress towards the end of his marriage to Alison Sharp. He and Jane married in 1972 and had a son, Nicholas, to add to his three by Alison (Simon and Stephen run a production company that makes film and TV adaptations of their father’s books; their brother, Timothy, a journalist, sadly died suddenly this year). Dawson writes that his infidelity to her didn’t trouble Cornwell, so it didn’t trouble her. “I know it’s the cultural convention through a million movies and TV series and books that women are the ones who break up a marriage by leading the man astray. And it’s BS because that denies the agency to the man. My father was there for 45 years at my mother’s side, would never look at another woman.”

The irritant in this relationship was not Jane but David. He “ran” Dawson as he might a double agent from his spy days. “There was stuff I only realised when I was writing. Taking me to Odin’s [a fashionable London restaurant in Marylebone] and seeing [Harold] Pinter at his usual table! I was nowhere close to thinking he was taking me there so that Pinter could see the young bird he was dating. Plain as day once I wrote it, but for years I never saw that.”

Worse, when not accidentally on purpose flaunting her, he was behaving as if they were on the run, hunted, spied upon, about to have their – his – cover blown. Leaving a shop in Lesbos, where they had a romantic break, he asked directions to the main beach and then after a few steps walked the other way. He even confused himself: having written deliberately in his contacts book that Dawson lived in London in NW3 rather than SW3, he misaddressed a love letter.

She says he had “been too long out of the field” and it would be easy to attribute his intentional confusions to force of MI6 habit, but she believes the instinct was acquired in childhood from his father, Ronnie, a conman who between frauds was often in jail. But while misdirection was Ronnie’s criminal MO, his son could lose his emotional bearings for real. After one night of “tender and true” lovemaking in Zurich she woke to have him order her to leave. “I can’t be this happy,” he explained. His addiction to paradox, his unhappiness with happiness, likely explains why he never left Jane for her.

“I think on some very fundamental level he had the notion that manhood was in the slammer. Because Ronnie’s first prison sentence was when David was very little, I think something got fused there: the notion that you can’t be free. He wanted to be free of what he himself had imprisoned himself in. I mean, nobody made him get married. Nobody made him have two marriages.” Or stay with Jane? “Or stay with Jane.”

For their meetings, Cornwell bought a flat in St John’s Wood, not far from his Hampstead home. It was their “safe house” but he was restless in it. I think of his claustrophobia. Was he capable of real love? “Oh, I think so. By definition. But he wasn’t capable of trusting it. I think he wondered what he would lose if he lost the discontent in his life and the friction and the paradox. I think he thought, perhaps quite rightly, that was the fons et origo of his talent. If he had allowed himself to be consistently happier, who knows? Maybe he would have written different books altogether. Maybe he would have just thrown his pen out of the window and never written again. I don’t know, but I know that was part of his considerations: being miserable and making people around him miserable from time to time, this was what generated the canon.”

Dawson, as it happens, never wanted to marry him, or anyone else – although she says she does not rule it out someday. She was the only child of devoted parents, but never wanted children. What she would have liked was to have been a proper old-fashioned, long-term mistress. “But that would be too settled for him, I realised afterwards, because it didn’t have enough moving parts. You can’t get rid of the wife, because if the wife knows you’ve left her for the other woman, there’s no tension any more, just a bad feeling all round. The deception and the hiding and the covering, the going for cover and living undercover, were an essential part of it.”

In the end, she told him she could not take their relationship’s “unnecessary Sturm und Drang” and began the process of leaving him. She parcelled up his jewellery and returned it by courier. He cajoled her back and celebrated by buying a cheval mirror for the bedroom, which made her feel like his “looking-glass whore”. She could no longer “hack” the sex. She felt like “one of those unlucky addresses that keep getting burgled”. Finally extricated, Dawson saw a therapist, who diagnosed her as “borderline clinically depressed”.

Yet there is no bitterness in the memoir? “I was responsible for my own life as much as he was for his. So I could have walked away at any time if I’d chosen to. And in fact I did, after two years.” She does write that women, and particularly wives, get a rough ride in Le Carré novels, often culpable for a husband or partner’s downfall. Three die from injuries to their throats, “the female organ of reproach”. Was Cornwell a misogynist? “I can’t say it’s by definition misogynistic to cheat on your wife. It clearly isn’t. That would be too facile. But I think there’s a way of cheating on your wife that’s more misogynistic and I think perhaps the misogyny in the books, there’s no question, came from his not really having women in his life as a child.”

Little boys get their understanding of women from their mothers, she thinks. His mother, Olive, left when he was just five and did not see him for 16 years. Cornwell writes in his 2016 biographical essays The Pigeon Tunnel that “in the absence of a mother or sisters I learnt women late, if ever, and we all paid a price for that”. Dawson concurs.

She went on with her life. The memoirs list her interim lovers: a TV executive, an “Old Etonian” headhunter, but mostly actors. She continued making audiobooks, ghost-wrote for other authors and in 1994 published her own novel, The Forsytes, a sequel to the Galsworthy novels. It was for this she assumed the nom de plume Suleika Dawson.

On a whim, 14 years after their split, she attendeda lecture delivered by Cornwell in London. He spotted her in the audience. The whole shebang resumed: the falling in love; the rampant sex; the flashy gifts; and, predictably, Cornwell’s inability to decide whether he was in or out. He asked whether she would like a child, and when she replied, “Never say never,” declared he would leave Jane for them. Yet when Dawson’s mother died of a heart attack and her broken father was admitted to hospital, Cornwell, the putative family man, barely took any notice, thanking her merely for not troubling him with the news earlier.

Still running the affair as a spy operation, Cornwell continued to book overseas couplings by proxy. By now, however, the “travel agency” guys were dead. For a trip to Elba, he told her to book the flight herself and sent her the fare in cash by post. The more she thought about it, the more it felt like “leaving money on the dresser”. She suggested he might arrange a credit card. There was a “bristling silence” on the line and then, “I think that’s a bit stiff.” Which was the last thing he ever said to her. They separated, this time for good. Why would such a trivial request cause him to break it off? “Good question. I think he just ran out of road.”

She means as a spy. He had lost his nerve. She originates the crisis to the funeral of another girlfriend he had been in love with, Yvette Pierpaoli, a leading French humanitarian killed in Albania. During the service his façade slipped and he blubbed in front of his wife. Having blown his cover once, could he trust himself not to do so again?

In his definitive biography of Cornwell, Adam Sisman quotes Jane saying, “Nobody can have all of David.” In The Pigeon Tunnel, Cornwell wrote that he was “born to lying, bred to it, trained to it by an industry that lies for a living, practised in it as a novelist. As a maker of fictions, I invent versions of myself, never the real thing, if it exists.”

“Well, you can ignore all the rest of it except the ‘if it exists’. That’s the core. I don’t think he ever really knew,” says Dawson.

A sceptic may wonder how much we can trust Dawson either. Sisman, however, has met her and tells me he is as sure as he can be she was indeed Cornwell’s mistress, although he is “less sure of [her] importance in his life”. He did not name her in his biography, partly for contractual reasons with Cornwell and partly because he did not want to cause unnecessary distress to Jane. Dawson seems far less worried about that. She could not publish the book until Cornwell was dead because he had the money to sue her. His widow, who had cancer, died a few months after him, in February last year. Would she have published had she lived? “If it was looking as though she was going to live a lot longer, I think I probably would have because it was still the truth of the story.” Would she have removed some details? “Very likely I would have taken a slightly different tone in some episodes, but I can’t believe that his second wife didn’t understand him very well. I can only imagine that she knew pretty much all of what was going on, at least in outline.”

I assume that, up in the heaven he did not believe in, Cornwell must be apoplectic right now, but Dawson disagrees. She thinks he would like her book and perceive no betrayal. “For your cover to be blown, you have still to be undercover, you have to be operative. I think being dead is as inoperative as you can get.” Besides, she makes him out to be clever, charismatic and, in bed, a stallion. “There’s a lot any guy would be happy to have written about him,” she says. “There were no scores to settle.”

She is not a frosty woman, but the sliver of ice in her brain, if not her heart, must have been among her attractions for him. After all, interviewing her is very like interrogating someone undercover. She will not divulge her real name, her exact age, where she lives, whether currently she has a lover. “We have the same skin,” Cornwell once told her post-coitally. “The same grain. Cut from the same bale.” You would never completely trust a word that man said, but on that I am inclined to believe him.

The Secret Heart: John le Carré, an Intimate Memoir by Suleika Dawson (HarperCollins, $34.99), out Nov 3

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout