Missy Higgins on a roll

After an intimate and devastating loss, startlingly frank singer-songwriter Missy Higgins has regained her perspective.

The highs would make you fly, but the lows make you want to die

And I was once there, hanging from that very ledge where you are standing

Nightminds, Missy Higgins

Pickles, she wants, “those big ol’ ugly gherkins”, and cheese, any cheese, with a cup of cold tea. It’s all she feels like today. Most days, really. Stronger than a whim, it’s almost like a yearning; something she just has to have. A craving? Yes, a craving. “I brought pastries,” I say feebly. The proffered box of buttery extravagance suddenly looks overblown and try-hard. “And fruit…”

The food sits heavy on the table between us. I scold myself inwardly: I should have foreseen this, having been there twice myself. I know what to expect when you’re expecting. Pickles are the go-to food for growing a baby, and the fact that Missy Higgins, 34, is currently performing this feat is hardly a secret. Not much about the life of the Melbourne singer-songwriter is. It’s why people love her.

Just five days previously, I’d watched Higgins charm 83,000 Ed Sheeran fans under a sky full of stars at Sydney’s ANZ Stadium. The record crowd was there to see the biggest-selling male artist in the world, but his personally chosen support act held them captive with little more than a piano and her bell-like voice.

Higgins flitted about the stage as if chasing butterflies, a sprite-like neo-hippie in a gossamer green maternity dress. She strummed her guitar. Sat at the piano, further back than usual, to make way for the bump. And she chatted to the jam-packed stadium like she was gossiping with friends, her unaffected Aussie drawl ranging across subjects romantic, personal, carnal and cosmic.

“We’re actually expecting another baby in a few months’ time,” she said, introducing her new single Futon Couch, a “straight-out, ‘f..k it I love you’” song written about her playwright husband, Dan Lee. A roar swept through the stadium like a tidal wave: 83,000 concert-goers wishing her well. “I just found out that she’s actually at the age where she can hear my voice,” she continued, dropping a casual gender-reveal. “This is going to be the first thing that she hears: an Ed Sheeran concert with all these people cheering. So that’s pretty awesome.” Her glow was visible from the cheap seats; it did battle with the stars.

Marriage and motherhood are the latest life experiences to have a profound impact on the psyche and therefore the art of Missy Higgins. Her upcoming fifth album, Solastalgia, is the first since giving birth to her now three-year-old son Sammy. But don’t expect a warm and fuzzy collection of lullabies. A self-confessed over-thinker, Higgins has taken maternal catastrophising to the extreme and produced an album about the apocalypse. Expect the unexpected when you’re expecting? “I’m just kind of glad I didn’t write a clichéd parenting album,” she laughs.

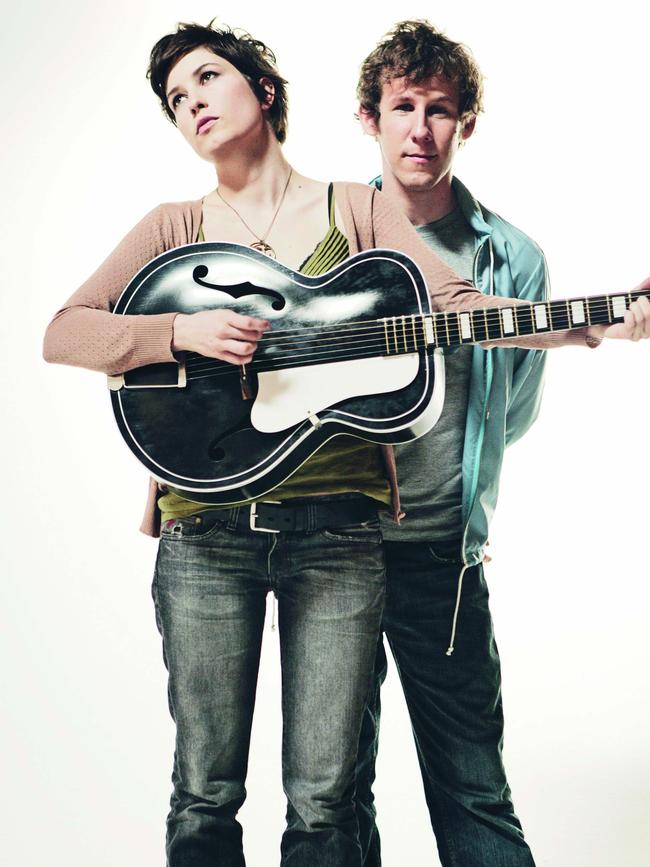

Melissa “Missy” Higgins arrived on the scene in2001 as a 17-year-old schoolgirl after winning Triple J’s Unearthed competition. Her sister had secretly entered the first song Missy ever wrote, All for Believing, a shimmering piano ballad she still includes in her set. Three number one albums and nine ARIA awards later, gently melodious songs such as Scar, Steer and The Special Two have earned residence in the great Australian songbook and Higgins a place in the hearts of millions. Unvarnished, real and often startlingly direct, she offers the perfect accompaniment to Sheeran’s busker-on-steroids authenticity. But she wasn’t always this unguarded.

Having battled depression since high school, Higgins has often felt the urge to hide. She struggled with the instant fame that followed her 2004 debut album The Sound of White; the huge success of her 2007 follow-up, On a Clear Night, sent her into a tailspin. A reluctant celebrity, she was uncomfortable talking about her private life and squirmed through three years of increasingly frenzied media speculation about her sexuality before telling a lesbian magazine in 2007 that she was “not so straight”.

In 2008, she did hide, took four years off to deal with a full-blown existential crisis and a crippling case of writer’s block. “I didn’t really have a choice,” Higgins says. “I tried to write. I rented a place above a flower shop in [Melbourne’s] Northcote for a year and I went in there every day. I tried to do what Nick Cave does – get all dressed up in your work clothes and take your briefcase and try to treat it like a job – but it just didn’t work for me.” She took her manager John Watson out for lunch and announced her decision to quit music. “I told him I didn’t love it any more and I wanted to do something with my life that had more meaning and made a difference in the world.”

She completed a year of indigenous studies at the University of Melbourne, travelled to India for her songwriter friend Ben Lee’s Hindu wedding to American actress Ione Skye and then kept going, on to Brazil, where she journeyed up the Amazon River. On returning to Melbourne she was still feeling lost when she received an invitation from her idol, Canadian alt-pop singer Sarah McLachlan, to join the 2010 incarnation of her all-female touring festival, Lilith Fair. “All of these fans came out in droves, and so many waited after the show to tell me how much my music meant to them,” Higgins says. “I felt so … silly and humbled. It hadn’t clicked before that this was something I should be really grateful for.” The fans were waiting when she emerged from her tormented sabbatical: her 2012 comeback album, the ironically titled The Ol’ Razzle Dazzle, sold more than 15,000 copies to debut at No. 1.

“She went through some dark patches and she put them into her art and the art became part of her life,” says older brother David Higgins, a fellow musician. “It’s made her even more genuine and relatable; at her concerts you see thousands of couples and friends, with their arms around each other, crying, singing along. They really love her.”

Second-trimester Missy is strong, happy, confident. Serene. Gone is the tomboy who, early on, countered the music industry’s fixation with image by chopping off her hair. Higgins’ new shoulder-length waves soften her features: her pixie-cute looks have ripened into beauty. “I’m quite a happy pregnant person in general,” she says. “I’ve actually been quite amazed at how well I’m coping with everything going on at the moment because it’s quite insane.”

Higgins had just finished organising next month’s national tour in support of Solastalgia – adding new dates as shows quickly sold out – when a certain ginger troubadour kicked it up a notch with a surprise invitation to join him on the local leg of his epic global tour. The tickets she’d already bought to Sheeran’s Melbourne show were given away to a fan through a competition on her Facebook page and suddenly she was playing to the biggest crowds of her career.

“The first show in Perth I was really freaked out, but I got used to it surprisingly quickly,” she says. “I remember thinking, ‘How am I going to perform to this many people because my shows are usually very intimate in nature in that I talk to the audience, they talk back to me, and I tell very long-winded stories that often go nowhere. You can’t afford to do that when playing a stadium. It took me one or two shows to get my feet and the rest of the tour I just loved it.”

Ahead of the tour, Sheeran told all and sundry that Higgins had been his “first big crush” when he was a boy. “He was 13 then, he was a baby, so it hasn’t been weird or anything between us,” she says, adding that she was surprised at the singer’s in-depth knowledge of her back catalogue. “He told me that The Cactus that Found the Beat, which I wrote for a Year 12 school project, was one of his favourite songs. He has my early EP and all the obscure B-sides, which is pretty lovely to think about.”

By the time her own tour kicks off, Higgins will be six months pregnant. Sammy was just six weeks away from entering the world when his mum wound up a nationwide tour in support of Oz, her 2014 covers album reimagining songs from Australian artists as diverse as Slim Dusty and The Angels. But she’d never before written songs as a mother. “Before I had a kid I was very good at procrastinating,” Higgins says. “I’d have all day to write songs and I’d leave it to the last minute and then I wouldn’t be in the mood. Now I know exactly what hours I have to do things in because Sammy’s at kinder or someone is looking after him.

“I don’t find it hard going between the head spaces because being with Sammy makes me really happy. I think when I’m spending too much time on my own I can get too in my head. I almost need to be lifted out of myself a little bit, which is what having a kid does.”

When a folk-pop song is working, it feels like alchemy: Joni Mitchell’s albums were once described as the perfect cross between professionalism and séance. Having found the complex balance between discipline and creativity – inviting the muse in while metaphorically punching the clock – Higgins found herself thinking about the end of the world.

It all started after she developed an “obsession” with apocalyptic literature. She read Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven, about a travelling theatre group that performs Shakespeare to the few survivors of a flu pandemic that’s decimated the planet’s population. She moved on to Australian author James Bradley’s Clade, which tracks the devastating effects of climate change over generations. This climate fiction jag led her to Naomi Klein’s non-fiction book This Changes Everything, “which in hindsight probably wasn’t the best thing for my over-active brain”, she says. Higgins became very, very scared. “There is still time to avoid catastrophic warming,” Klein writes in her ambitious 2014 polemic, “but not within the rules of capitalism as they are currently constructed.” This was more terrifying than any zombie apocalypse.

“I’ve come to terms with it now and I know it’s the right decision but I went through a good year of really grappling with the ethics of bringing a child into a world that’s facing climate change,” Higgins says. She felt guilt whenever she looked at Sammy: how could she have thought this was a good idea? What had she done? But there was another factor amplifying these roiling emotions. Something Higgins has kept to herself until now. Something intimate and devastating that she reveals, not casually, but with new-found candour. It’s an indication of just how far she has travelled from the guarded 20-something whose self-belief foundered in the glare of a global spotlight, who built a fortress around herself rather than admit she liked girls as well as boys.

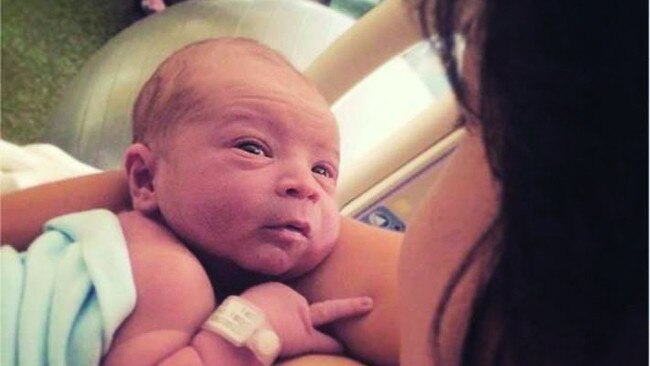

Gathering up crumbs from the table with her forefinger, she says: “I had a miscarriage between Sammy and this baby and the whole thing was kind of set off by that, too. I think it started when I was really hormonal with the pregnancy and then that didn’t work out. I had very mixed emotions about it; I didn’t know whether to feel happy or regretful. I was all over the place.

“Even before the miscarriage, I was in a pretty dark place; maybe reading all this climate fiction, it was all feeding itself. It was a strange time. And it just got me thinking a lot about the end of the world and really morbid things.

“I guess when you put having a child into that, your idea of time becomes so much bigger. It’s not just about my lifespan any more; it’s about an endless future of my son’s children and their children. Suddenly, your responsibility is not just for this tiny fraction of time; it’s for eternity, which is so massive that you really shouldn’t dwell on it for too long.”

It was around this time Higgins stumbled across the word “solastalgia”: a mouthful, she admits, but it seemed to perfectly define the mood of her new album. Australian academic and philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term in 2003 to describe a complex concept that can best be summed up as distress caused by environmental change.

“It’s that sense of sadness and loss that people experience returning to their childhood home or their farm after it’s been affected by environmental change,” Higgins says. “It’s a sense of nostalgia for something that hasn’t actually gone anywhere but it doesn’t look the same as it used to. There’s a sadness about that.”

Higgins mostly avoids sermonising in favour of creating narratives around dystopian scenarios featuring blood-red moons and globe-ravaging floods. Romance still figures heavily. “Love stories are one of those things that will happen regardless of the situation,” she says. There’s even a song about aliens.

“That’s the thing with Missy – once she decides to do something she doesn’t do it half-heartedly,” says friend and collaborator Butterfly Boucher. Boucher, an Australian singer-songwriter based in Nashville, produced The Ol’ Razzle Dazzle and worked with Higgins on much of Solastalgia. “She is absolutely who she puts out there,” she says. “What she sings about is straight from her gut, which is what makes her lyrics so relatable to people. Honestly, it felt like these lyrics were on the tip of her tongue, just waiting to fall out and be in a song.”

Confessional lyrics have charted Higgins’ course through teenage crushes and fully fledged heartbreak, but the new songs are more akin to what she calls “very tiny apocalyptic novels”. She’s also stepped outside her comfort zone sonically, into a more programmed soundscape. The trademark piano and acoustic guitar are folded into drum loops and delicate slivers of electronica that occasionally erupt into spacey synth burbles. Floating above it all, still: that God-given voice, soothing and pure as a Tibetan singing bowl. “She wanted to experiment with sound and techniques without betraying the essence of who she is,” says the album’s co-producer Pip Norman, who has worked with TZU, Troye Sivan and Dan Sultan. “Any production ideas had to speak to her songwriter’s heart first and foremost.”

Higgins has always had a social conscience but hints of Solastalgia’s urgent political themes emerged early in 2016 with Oh Canada, a charity song she recorded with Norman in response to the Syrian refugee crisis after seeing images of a little boy washed up on a beach in Turkey. Son Sammy was just four months old. “I was actually really relieved that I felt inspired to write a song,” she says. “It’s funny, but being female, having kids, you’re afraid your songs will get watered down.” Instead, motherhood sharpened her focus. “I’ve noticed there are so many driven mothers out there because we have to prove we’re not going to become a shell of our former selves just because we’ve become mothers. It’s actually going to make us a better human being, more colourful and stronger.”

Higgins was born into a musical family. Her father Chris, a GP, is a classically trained pianist and she took lessons from the age of six. As a young girl, she would lie under the piano for hours as her big brother David played and, at 14, she “not entirely legally” began to sing with his jazz-funk band at clubs around Melbourne. “She kept getting all these encores, no one would let her get off the stage,” David says. “It was obvious how awesome her talent was at such a young age.”

Following her two older siblings to Geelong Grammar, she soon found her way into its acclaimed, jazz-focused music school. “This little skinny girl came and introduced herself and she sang – I can remember – Cry Me a River and it just blew me away,” says Paul Rettke, the school’s long-time music teacher. “Here was this 15-year-old girl and she sounded like a 40-year-old black woman, like she’d lived. I said, ‘Who is this?’”

Higgins was a boarder and spent every spare moment in one of the music school’s soundproof booths, sequestered with an upright piano and a jumble of churning emotions. “It was just my favourite place in the world,” she says. “I used to lock myself in there and bash at the piano, singing my adolescent, hormonal heart out.”

The love story of the singer and the playwright begins not at the end of the world but in Broome, Western Australia. In 2013, Dan Lee was working at the library in the far-flung pearling paradise, where he shared a house with one of Higgins’ friends. After meeting him at the house one day, she began “popping round for tea” with her friend more and more frequently. “I became a bit creepy I think,” she confided to her 83,000 new friends at ANZ Stadium. “But it worked. I got him.”

She and Lee sang the glam-rock Kiss classic I Was Made for Lovin’ You together at a mutual friend’s wedding and the relationship soon hit warp speed. Six months after they met, Lee proposed in the kitchen. Five months later, Higgins was pregnant with Sammy. The couple reprised the prescient Kiss song for their 2016 wedding, a private affair held at a not-for-profit inner city farm in Melbourne, and instead of exchanging rings, they had matching arrow tattoos etched onto their feet.

Higgins has never been happier, says her brother David, “so rosy-cheeked and in love”. And Lee brings out her goofier side. This is the Missy that leapt excitedly into David Hasselhoff’s arms on stage at the 2005 ARIAs, straddling the startled Hollywood visitor while accepting her Album of the Year award. “I’m just so glad my undies didn’t show!” she said later. The Missy that clowns around on her Instagram, and recently posted a photo of herself sprawled on the ground after a tumble during sound check. “I fell off the bloody stage!” she wrote. It’s the Missy of Futon Couch, a jubilant ear-worm of a song that lightens the mood of her dystopian new album. “That song is an anomaly,” she says. “I got to the end and I thought, ‘I should probably write a song about Dan – it won’t really fit but who cares, I’ll do it anyway’.”

Having travelled to the dark edges of her subconscious to find the unrest and tension that fuels the creation of art, it’s fitting that this final, climactic burst of joy should come from somewhere close to home. Family, the blessed routines of domesticity, and a determined positivity have replaced the confused and angsty questing of her youth. Her husband helps quiet the inner dialogue that foreshadows depression’s dreaded swoop. Son Sammy reminds her what’s worth fighting for. And the new life inside can’t help but make her smile.

“It’s pretty exciting,” she says. “I was really sure I was going to have a boy because there’s just all boys in our family. I burst into tears when the lady told me on the phone that it was going to be a girl. I was so emotional, because I really wanted a girl but I wasn’t allowing myself to get my hopes up.”

I’m still feeling bad about the pickles. Australia’s beloved songbird has been denied what her pregnant body is telling her she needs. She’s flown to Sydney for this interview from Brisbane, where she closed out the final concert of Sheeran’s 12-date Australian tour with a surprise duet on his smash hit Perfect. She’ll fly out as soon as the interview’s finished, home to Melbourne to be reunited with her husband and son. That’s three states in one day. She’s 18 weeks pregnant.

But the “happy hormones” are surging. She peers politely inside the box of pastries and extracts a quarter of a blueberry muffin. “These look nice,” she says, dimples flashing. “Thank you.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout