Catch Me If You Can conwoman’s rebirth as a charity money magnet

A chameleon with a collection of wigs and a penchant for the high life, Jody Harris used stolen credit cards and driver’s licences to impersonate her victims, brazenly walking into banks to drain their accounts. Then she became one of the nation’s most active fundraisers for charitable causes.

Anita Mulligan was at the corner of Lonsdale and Elizabeth Streets in Melbourne’s CBD when a sudden fall and chance encounter with a stranger upended her life. In a mishap that could have happened to anyone, she slipped and momentarily knocked herself unconscious on the busy thoroughfare. People around her rushed to her aid. It was just Anita’s bad luck that among them was someone who wasn’t there to help anybody other than herself. Swooping in and taking charge, Jody Harris feigned both concern and medical expertise.

“She pretended she was a doctor,” Anita recalls. “She actually moved me, when they had me immobilised as per what triple zero told them to do. The hospital said she could have made me a paraplegic for the rest of my life, or actually killed me. And in the meantime, she stole my driver’s licence and that’s how she got all this money out of me.”

That was 18 years ago. At the time, Jody was in the midst of a Hollywood-worthy crime spree that would see her dubbed the “Catch Me If You Can” thief as she taunted police, left a trail of frauds across three states and became the nation’s most wanted conwoman.

A chameleon with a collection of wigs and a penchant for the high life, Jody used stolen credit cards and driver’s licences to impersonate her victims, brazenly walking into banks to drain their accounts. It all went to fund an extravagant lifestyle of luxury hire cars, five-star hotel rooms, business class flights, designer clothing and even a designer poodle. She had serious relationships with not one but two Victorian policemen along the way, with law enforcement something of a strange obsession throughout her life.

In July 2006, within months of scamming Mulligan, Jody was arrested in a blaze of publicity that was only heightened by her mother being the well known prisoner advocate Debbie Kilroy, and her stepfather being former rugby league star Joe Kilroy.

Back then, bank security loopholes, disguises and a good line in chat allowed Jody to get her hands on other people’s cash. Nearly two decades on, it’s no longer an analogue world.

Jody, now 46, has turned over a new leaf, started a new venture and become a prolific fundraiser for charitable causes. She has attracted hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations, some via the online fundraising platform GoFundMe but others directly into her business’s bank accounts, with limited oversight and plenty of questions about how the money is being distributed.

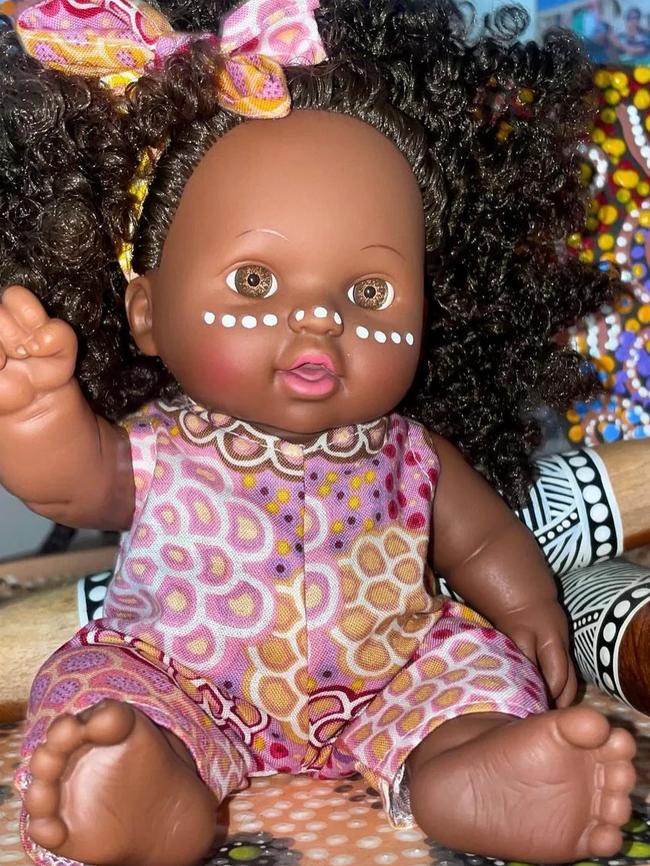

“Hi we are Bee & Jo from DreamtimeAroha,’’ reads the Instagram post from three years ago. “We are proud married Indigenous women with three amazing dogs living in Meanjin (Brisbane). We make beautiful Aboriginal Jarjums for all children.”

By the time Dreamtime Aroha launched online in April 2021, Jody Harris had become Jody Thomson, adopting the surname of her now estranged wife, Rebecca Thomson. While promoted as a joint business, it was registered solely to Jody’s new name and a PO Box in Brisbane. The business set out to sell Indigenous dolls, but it seemed Jody had inherited her mother’s passion and knack for advocacy and Dreamtime Aroha quickly became a high-profile campaigner and fundraising juggernaut for Indigenous issues.

So successful was the business in fundraising that when GoFundMe released its top 10 Queensland campaigns of 2022, Dreamtime Aroha held three of the spots. The list made a news story in the Townsville Bulletin, in which Jody is quoted as saying: “During 2022, we successfully helped more than 400 families with nappies, food, formula, toys, shoes, Christmas hampers and over 50 mutual aid causes paying for flights to get women out of DV (domestic violence) situations, paying back rent, buying fridges and paying for essential medications.”

If Jody was worried the publicity might have led to scrutiny, she needn’t have been. There was no reference to her lengthy criminal record for fraud, and her fundraising continued.

It had all started with a series of comparatively small GoFundMe campaigns in late 2021 and early 2022, social media posts reveal. At first, Dreamtime Aroha asked for donations to send dolls to kids. But it soon branched out with a broader campaign for money to buy Covid tests, in an appeal citing “a horrific situation in Palm Island where they have brought in makeshift morgues to support the anticipated death count”. Tests would be sent “to ANYONE who can’t afford them”, the business added. It was followed by Dreamtime Aroha GoFundMes to “help Aunty Gloria rebuild her home” after flooding in northern NSW, and to buy “sleeping bags, swags and warm gear” for Brisbane’s homeless.

Then Dreamtime Aroha hit the fundraising big time, piggybacking off a news headline that highlighted “disgusting” grocery prices and “mouldy” fruit sold in remote Indigenous communities. Launched in July 2022, this GoFundMe pledged to buy “nappies, baby formula, wipes and non-perishable food items” for the Queensland communities of Cherbourg, Mornington Island and Aurukun. A note at the end added that “items will be purchased and sent at our discretion and to what community we feel can benefit most”. Donations were halted at $150,255.

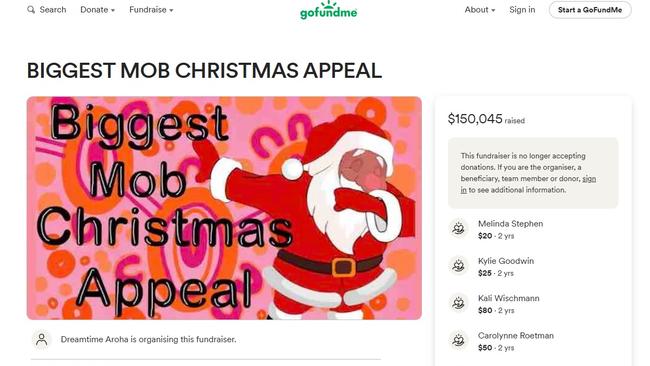

On a roll, Dreamtime Aroha launched its “Biggest Mob Christmas Appeal” GoFundMe in September 2022, raising a further $150,045. Donors were told Dreamtime Aroha was “handing out vouchers and sending funds to Blak community organisations and individuals in need this Christmas at our discretion”. Cherbourg was again cited as benefiting.

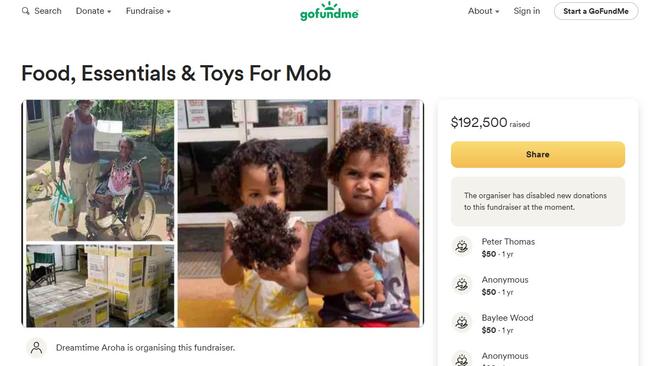

A “Food, Essentials & Toys for Mob” GoFundMe launched in December 2022 became the business’s greatest fundraising hit to date, raising $192,500 for Dreamtime Aroha to distribute at will. A Christmas appeal on GoFundMe in 2023 raised a further $82,873.

In total, at least 12 GoFundMes were organised by Dreamtime Aroha in just over two years, raising more than $700,000 to support Aboriginal people and the marginalised. Dreamtime Aroha’s updates and social media posts suggest GoFundMe released these funds to Jody’s business to distribute aid. And that’s only part of the story. The business has also fervently fundraised on social media for other causes, with donors directed to transfer money directly into Dreamtime Aroha’s bank accounts for distribution.

In March this year, for example, a story about a tradie cable-tying three Aboriginal children found swimming in his pool in Broome made headlines. Dreamtime Aroha stepped in with a social media fundraiser, raising enough to send family an inflatable pool and $11,000. It led to feelgood national media reports – gold for Jody’s brand. Again, her serious history of fraud went unacknowledged.

Jody has said her inbox is regularly full of people pleading for financial assistance, and she champions some of these cases. It’s impossible to know exactly how much has been donated to Dreamtime Aroha bank accounts from these appeals, on top of the GoFundMes, as Jody has declined to be interviewed or to answer any questions. Instead, Dreamtime Aroha holds itself accountable by posting images online of supplies and receipts, along with grateful messages from recipients.

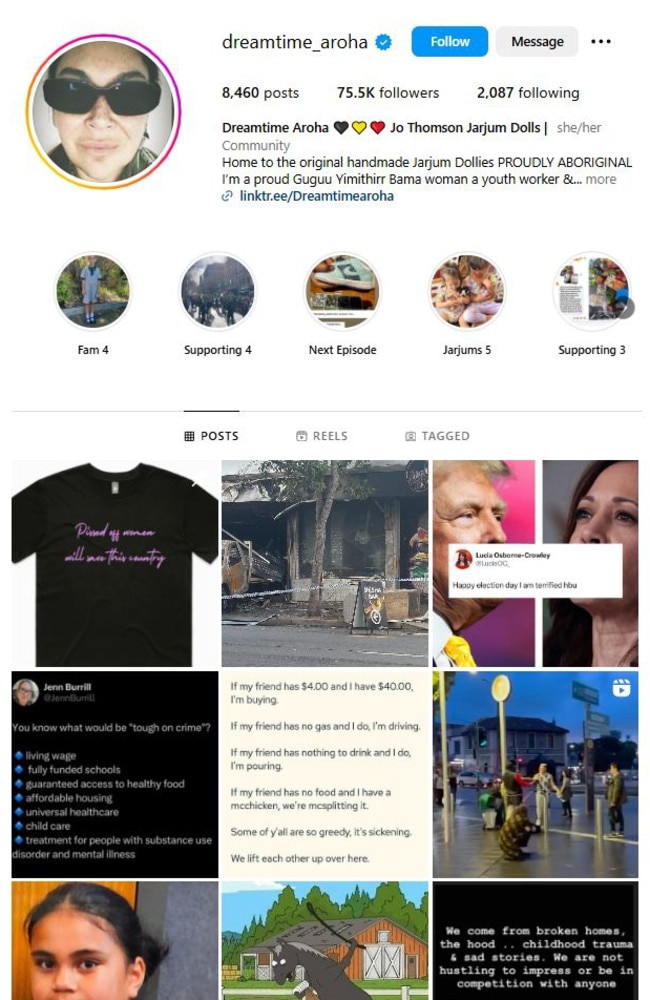

Today, its social media pages would be the envy of any e-commerce site, with more than 75,000 supporters on Instagram alone, where it posts frequently about Indigenous, LGBTQ and Palestinian affairs. Influencers, activists, media personalities and brands have rallied behind Jody, and many posts have logged thousands of likes and shares.

In one instance that demonstrates her influence, her business went viral for publicly shaming upmarket venue Redleaf Wollombi in NSW’s Hunter Valley, and wedding guests, for photos posed in front of an artwork depicting what Dreamtime Aroha described as “Aboriginal people being slaughtered by colonisers”. Reality TV star Abbie Chatfield shared the post to her almost half a million followers, and the story was picked up by the New York Post. (The venue apologised and said the painting, Views of Brazil, 1829, depicted Portuguese colonial violence in Brazil.)

Ordinary Australians have responded by opening their hearts and wallets to support Dreamtime Aroha’s charitable campaigns. On its face, it is an incredible story of redemption: awoman who went from picking pockets to having people reach into their own to support her vision for a fairer world.

Except Jody’s past won’t go away. In Australia’s two-degrees-of-separation Indigenous communities, her rise is discussed frequently and at times sceptically. Apart from concerns that she is not disclosing the nature and extent of her criminal history, critics have raised a range of allegations, including that Jody has harassed Aboriginal small business owners and community members. Behind closed doors, they share stories and demand something be done, but are fearful of a woman they believe wields great power and is practised at shutting down others and claiming victim status.

It could have been any number of people to ring the bell on Jody’s past, but as it happened it was Regina Bonner Moran, a vocal Aboriginal activist who runs independent support service Stop Black Deaths in Custody Australia. (If the name sounds familiar, it’s because she’s the granddaughter of Neville Bonner, the first Indigenous member of Federal Parliament.)

Bonner Moran knew Jody’s backstory and was alarmed and frustrated that a major fundraiser’s serious fraud-related convictions weren’t being mentioned. Dreamtime Aroha was coy on this history as it appealed for donations on Instagram. On her account Jody now describes Dreamtime Aroha as “Home to the original handmade Jarjum Dollies PROUDLY ABORIGINAL I’m a proud Guguu Yimithirr Bama woman, youth worker, gay & formally incarcerated”. The account has featured other references to prison time. However, as recently as August, the bio did not mention incarceration, and any mention of her previous name Jody Harris, and her history of fraud, could not be found.

It didn’t help that when Bonner Moran spoke last year to some of the homeless living in a tent city in Musgrave Park in Brisbane, near a new CBD bridge named after her grandfather, none seemed to know that fundraising was occurring on their behalf. Bonner Moran was also in touch with other Aboriginal women who shared her concerns that Jody was effectively operating an unregistered charity. While Dreamtime Aroha declares it is “not for profit”, there is no record of it on the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission’s public register. So who, if anyone, was watching over it?

In August, annoyed that the public remained in the dark, Bonner Moran posted on Instagramthat Dreamtime Aroha “IS JODY AKA HARRIS”, with screenshots of historical news stories about Jody being the “Queen of con artists”. Jody was “a convicted criminal with a seedy past using fundraising platforms to raise money on behalf of our most vulnerable Aboriginal people”, she posted. She also blasted Jody’s fundraising efforts as “trauma porn” and claimed it was diverting money from others trying to raise funds in the space. Nothing seemed to come of it.

In an apparent contrast to Bonner Moran’s concerns, Dreamtime Aroha’s social media accounts have shared many photos of essential items including tents, sleeping bags, groceries and charging equipment Jody has purchased for the homeless in general, and for those on the streets in Brisbane’s West End, as well as ad hoc testimonies from recipients – including some local organisations and homeless people effusively praising Dreamtime Aroha.

“A big thank you to our friend Dreamtime Aroha who has made this possible and is a huge support to us,” community group Feeding 4101 posted last year, after stocking a West End pantry with donated groceries for the homeless.

But none of this has alleviated the concerns of Bonner Moran and her circle. “THIS IS NOT ABOUT PEOPLE HAVING A PAST!” she posted on Instagram. “It is in the PUBLIC INTEREST that AUSTRALIANS especially MOB have full knowledge and it’s disclosed. Posting screenshots on your INSTAGRAM ACCOUNT is NOT PROOF.”

In an apparent reference to Bonner Moran, Dreamtime Aroha posted on the same platform in mid-August: “Do not send me posts from that desperate for attention drifter RB. I do not care what it has to say … she needs to put the ice pipe down and get herself into rehab.”

Bonner Moran dismisses the drug allegation as a false slur and says Jody’s past offending and the lack of transparency around the money going in and out of Dreamtime Aroha’s bank accounts has touched a nerve in Indigenous communities, where there is acute awareness that fraud has robbed many people of the support they desperately need. “Fraud is a no-go in our community, because we’ve had multiple cases where people have come in and ripped our community off,” Bonner Moran says. “It affects all of us, especially those organisations that do the hard yards and are underfunded.”

Cherbourg, 265km northwest of Brisbane, has been one of the main beneficiaries of Jody’s fundraising but there are some concerns there too. Dreamtime Aroha has shared many pictures online of supplies it sent to the Gundoo daycare centre in Cherbourg for distribution throughout the community. “The community of Cherbourg thank Jodi, Dreamtime Aroha and all the amazing people who donate,” a Gundoo staffer commented on Facebook – later screenshotted and shared by Dreamtime Aroha. “The wonderful Christmas food of fruit cakes for our Elders and cake mix and icing for our little ones to make cakes with their loved ones (making memories) is such a treat. All the nappies and food items are all so gratefully received. THANK YOU !!!”

But Elvie Sandow, the centre’s longtime president and former Cherbourg mayor, says she didn’t know about the business or its fundraising until someone recently called her to check up on Jody. “Haven’t heard of ’em. If it was significant, I would know,” she said, promising to do some digging.

The next day, Sandow says, she checked with the centre’s director, who confirmed Dreamtime Aroha had donated goods through a staffer who no longer works there. Unable to immediately confirm how much was raised or donated, Sandow says she is troubled that Cherbourg and the centre were used in fundraising drives without full visibility and control of donations and spending. “If it was a cash donation, we’d spend it on resources for our kids within our centre,” she says.

On Mornington Island, a remote community of 1000 people in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Kyle Yanner does not have a glowing review for Dreamtime Aroha either. Yanner says that while he was mayor from 2020 to 2024, he had a run-in with it over false stories about the community. Dreamtime Aroha had “put out a bullshit story that our girls are selling themselves” to survive, he says. “I remember seeing this story about my community that was just totally wrong and totally false. I rang her up and asked her what the heck she’s doing, giving misleading stories.”

Several other people say they remember being shocked about the Mornington Island social media post, but it appears to have been taken down. Jody is said to have explained that she heard the story through a local nurse.

“I asked her … ‘If there’s any stories you want to put out, see me for details first’, as I was a representative of the community, obviously, mayor,” Yanner says. “She reckons, ‘Oh, well … you can get stuffed basically’.”

Karina Hogan is a journalist, mother and foster mother who has worked at the ABC and is a board member of registered charities. She had a rough upbringing in Woodridge, south of Brisbane, and as a teenager met Debbie and Joe Kilroy’s son, Joshua. Hogan says that at age 14, when a lot was going down in her large Aboriginal and South Sea Islander family, she was taken in by Debbie.

As an adult, Hogan was on the management committee of Debbie Kilroy’s charity Sisters Inside, before falling out with Debbie. It was a tumultuous time at Sisters Inside, with Hogan and three other board members listed in charity records as resigning in the same month, August 2021. Amid the fallout, someone (Debbie was never suspected) targeted her with abusive, anonymous messages, warning her to watch her back and falsely calling her an ice addict, she says.

Fake Instagram accounts also appeared in Hogan’s name, and started sending messages to people. Hogan had to explain it wasn’t her. In one case, an Aboriginal artist with a large social media following who’d asked Jody about her Indigenous identity received messages from a fake account called karina_hogan_offical. Hogan suspected Jody was somehow involved, even before she spoke to someone who had been close to Jody; this woman told Hogan she’d gone to open Instagram on a laptop she believed was used only by herself and Jody, and it automatically asked for a password to log in to an account named karina_hogan_abc. Had Jody operated it?

Cherylea Walker is an Aboriginal small business owner from Karratha in WA’s Pilbara region. She specialises in handmade bush remedies inspired by her Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi family. Launching a line of Aboriginal dolls, she wrote on Instagram that she was “inspired by the many beautiful ladies before me”. Her “Pilbara Dolls” highlighted the region’s 30 different language groups. Other Aboriginal doll businesses sent her encouraging messages, but Jody’s went on the attack.

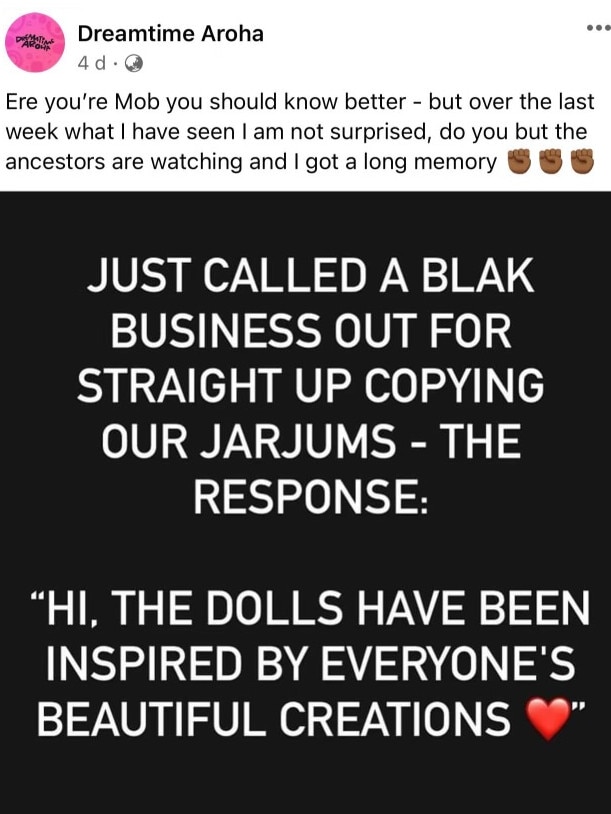

“Looks like an exact replica of ours truly. ‘Inspire’ Yeah not cool,” Dreamtime Aroha posted, accusing Walker of copying another business’s products too. On Dreamtime Aroha’s Instagram, followers were told: “JUST CALLED A BLAK BUSINESS OUT FOR STRAIGHT OUT COPYING OUR JARJUMS – THE RESPONSE: ‘HI, THE DOLLS HAVE BEEN INSPIRED BY EVERYONE’S BEAUTIFUL CREATIONS’.”

Walker believed the differences between Dreamtime Aroha’s dolls and hers were obvious, and posted to her small following that there was a lot of negativity on social media. “There really is no need for it. There is more than enough room for us all to succeed. Strong women should support each other and not bring each other down. When women support each other, incredible things happen,” she wrote.

Contacted by The Weekend Australian Magazine, Walker says she wanted to use the dolls as an Indigenous learning tool in daycare centres and schools. “She pretty much straight out attacked me. I was fairly new in business. I stopped doing the dolls then,” she says.

A separate business run by an Indigenous family had just launched a line of Aboriginal dolls when, among the messages of support, came one from someone called “Mrs Tee” on Instagram: “Do you feel bad stealing and profiting off other Blak mob? Get your own ideas.” The trail appeared to lead back to Jody. (Jody declined to say if she used that account or any involving Karina Hogan’s name.)

Another Indigenous woman says Dreamtime Aroha sent her organisation goods after asking the public for donations. But the organisation’s board members said they hadn’t approved the appeal or Dreamtime Aroha raising money into its bank account for the goods, she says. “She could have spent the exact amount that got donated. But the issue is, no one should ever be collecting with their account. It was a red flag to me.”

Putting aside Jody, some Indigenous community members are concerned that if people can operate as unregistered charities, fundraising in opaque circumstances where only the fundraiser knows how much money is going in and out for specific causes, it opens the door for those with ulterior motives. They fear that when things go wrong, the entire charitable community and those they help will suffer.

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, which registers and regulates Australia’s 60,000 charities, says it “does not have any jurisdiction over fundraising, [which] is regulated by state bodies”, but adds that “a key part of our role is to promote trust and confidence in the charity sector”. Donors are urged “to be careful” when using crowdfunding sites where it could be hard to check a campaign’s legitimacy, a spokeswoman says.

Similarly, Queensland’s justice department warns sites such as GoFundMe come with potential risks. “We always recommend only donating to registered charities or people and organisations you know personally to avoid issues,” a department spokeswoman says.

Anyone fundraising in Queensland is committing an offence if they don’t have required approvals. One-off charitable appeals from non-charities must be sanctioned by the state’s Office of Fair Trading, with audited financial statements required within four weeks of the appeal ending, with limited exceptions. Alternatively, existing charities can authorise others to fundraise in Queensland. But the charity’s name must be used, and that hasn’t publicly been the case in Dreamtime Aroha’s appeals.

The justice department spokeswoman says the easiest way to see if an organiser is properly authorised to fundraise is to check the state’s public online register. Dreamtime Aroha isnot listed on the register, or on similar registers in other states, and Jody won’t say how she is approved to fundraise.

Geraldine Menere, head of not-for-profit law at charity Justice Connect, says organisers raising money nationally need to comply with each state and territory’s laws, not just where they are based. Justice Connect has long described Australia’s fundraising laws as a mess, and hailed a victory when federal, state and territory treasurers agreed on a set of consistent fundraising principles for charities last year. But Menere says states have been slow to implement the principles into their local laws, and most jurisdictions “don’t contemplate online fundraising, and especially not through things like GoFundMe and Facebook”.

Money has always been at the heart of all trouble for Jody, and to understand how far she has come you have to know some of her history. In Kilroy Was Here, a 2005 biography of her mother Debbie, Jody spoke of a fixation that landed her in trouble for crimes of deception many times over. “I loved money, and I didn’t really care how I got it. And money also meant getting away from them,” she said.

The book details Jody’s difficult early life after Debbie, who has never claimed to be Indigenous, gave birth to her in Brisbane at 17. A persistent question about Jody is how she is Indigenous, but Debbie has been consistent about this for many years. In the book, Debbie explains that Jody’s biological father was an Aboriginal man who’d been adopted as a baby by a white couple. Given the pseudonym Matthew Parson in the biography, he is said to have been prone to extreme violence, and Debbie left him before Jody turned one.

When Jody was about five, Debbie started seeing “Smokin’ Joe” Kilroy, a supremely talented rugby league footballer whose nickname came from his speed. Joe, a South Sea Island and Aboriginal man, was also a member of the Black Uhlans outlaw motorcycle club, the book says. As a little girl, Jody literally stumbled upon the couple’s side hustle when she came across large bags of marijuana in a spare room.

Jody was 11 when, in 1989, both of them were jailed. Debbie was sentenced to six years for marijuana trafficking and heroin supply; Joe, who’d thrilled fans in the inaugural Brisbane Broncos squad a year earlier, got a three-year sentence for marijuana trafficking.

After seeing a friend stabbed to death in prison, Debbie vowed to turn her life around. She went on to become a lawyer, founded Sisters Inside, and was awarded an Order of Australia Medal. But after her parents were jailed Jody slipped into a life of crime, developing an early knack for swiping handbags to get to women’s credit cards. As she grew older, she would phone police stations or turn up in person to hang out. She sent one Melbourne constable she spoke to, Brett Bardsley, a picture of herself in heavy makeup wearing a black lace bra. She was 15 but, according to Bardsley, said she was 20 and that her name was Jodie Harding.

Jody became a regular visitor to Bardsley’s Chelsea home. Inevitably, it ended badly, with Jody arriving one day with a woman who explained there had been an accident. Jody, driving Bardsley’s car, had collided with the woman’s car. By then she was 16, not 21 as Bardsley thought, and was not legally allowed to drive. Bardsley sent Jody packing but took the blame for the crash to cover for them both, resulting in him being fired and charged when the truth came out. Jody had fibbed to him about going to a prestigious Brisbane girls’ school, and claimed her father was an advertising executive. When Bardsley asked why she had spun such a tangled web, she responded: “I can’t help myself. It’s just the thrill.”

In 1998, aged 20, Jody made headlines for a bizarre escapade. She’d gone to a police uniform supplier in Brisbane, leaving with a hat, badge and a name tag swiped from a mannequin. Next, she hired a white Commodore sedan, similar to police cars of the day. In full disguise, she was waved into the underground carpark of the Queensland Police Service headquarters in Roma Street, and walked directly into the high-security building. Police only realised later, and she was charged as Jodie Pearson-Harding with offences including fraud and forgery and posing as an officer. Harding was her mother’s maiden name. Jody and those close to her have said Pearson was the surname of her biological father, who has since died.

At the age of 21 she was facing eight years’ jail for dishonesty offences, principally theft and misuse of credit cards, and was appealing the severity of her sentences. She succeeded in getting a small reduction, though the legal fraternity had little confidenceshe could go on the straight and narrow, with the 1999 Court of Appeal judgment saying she showed signs of being an “incorrigible thief”, incapable of reform. They were right to be concerned. Jody’s obsession with money, and with police, was only growing. A Victorian police constable, Andrew Twining, met Jody through dating service RSVP in 2006, fell in love and proposed to the woman he thought was a flight attendant. Jody accepted, just as her criminal career was reaching a crescendo.

Horror stories were piling up of Jody impersonating women and leaving them with tattered credit ratings and driving records. A Melbourne charity worker complained: “She was even able to change all my personal details on the cards to hers to the point where, when I tried to change them back to mine, I could hardly prove who I was anymore.”

Victorian police realised they had a serial conwoman on their hands and turned to the Herald Sun, which ran a front-page story breaking the news that an “elusive swindler” was “preying on women in three states”. Jody phoned and taunted detectives, and deliberately left behind photos at an address raided by police.

Twining hesitantly agreed to help his colleagues and arranged to meet Jody in the early hours outside a Sydney Irish club in July 2006. Finally conned herself, she was arrested and ordered to serve at least three and a half years in NSW and an extra year in Victoria.

The scars from Jody’s crimes run deep. Anita Mulligan worked at ANZ bank and was buying her first property after a separation when she fell in Melbourne’s CBD and Jody purported to help. Anita says Jody phoned her in hospital daily to check on her welfare, but in fact was just keeping tabs on her while stealing tens of thousands of dollars of her savings. “I had to have my name cleared in case I was actually involved in this fraud. For about a year, all my accounts had to be locked down,” she says.

Anita had made a public appeal in the Herald Sun story for help in catching Jody – and Jody called her a “stupid bitch” from the back of a police wagon after a journalist asked if she would ever say sorry, she says.

Another of Jody’s victims, former flight attendant Leah Jury, still has strong feelings about the woman who scammed her on a Qantas flight from Brisbane to Melbourne in March 2006. Jury was off duty and sat next to Jody in business class. Jody wore gold and diamond jewellery, carried a Louis Vuitton bag and told Jury her parents had just bought into Melbourne’s Toorak. Flight attendants ran out of Crown Lager, so a manager offered Jody something from economy. “I don’t know what they have in economy, I’ve only been in economy once in my life,” Jody replied.

While Jury got up to use the bathroom, Jody swiped her driver’s licence from her unattended bag, later using it to drain her bank account of $22,000. “I do have a lot of empathy for people,” says Jury, now a nurse. “But people like her just make my blood boil.”

GoFundMe says its “standard due diligence process has been followed” for Dreamtime Aroha’s fundraising. “The fundraiser in question was verified in line with these checks.”

Rebecca Thomson declined to comment for this article but has told friends she wasn’t involved in Dreamtime Aroha’s social media posts, and that all of the business’s bank accounts were in Jody’s name.

Jody could have a powerful story of reform and making amends for past wrongs, with her doubters explained away. But a law firm representing her and Debbie communicated Jody’s refusal to respond to the allegations raised by her critics. It also sought to stop publication of any report about “utterly false” allegations against Jody. There had been “unfounded, relentless and malicious attacks” online alleging she was not of First Nations descent, had acted dishonestly or fraudulently and was in some way misleading or deceiving donors and beneficiaries of her charitable work, the firm said.

On Dreamtime Aroha’s Instagram on Saturday, November 9, Jody posted a picture of herself in an Aboriginal arts program as a prisoner 27 years ago. An accompanying message said she started offending when she was 12 or 13, at first for survival to escape a relative who repeatedly raped her. She has now been “home for well over 12 years and crime free for much longer”, is in therapy and works closely with young Aboriginal girls in the prison system.

Do you know more about this story? Contact David Murray at murrayd@theaustralian.com.au