Maverick barrister Andrew Boe: why the justice system is broken

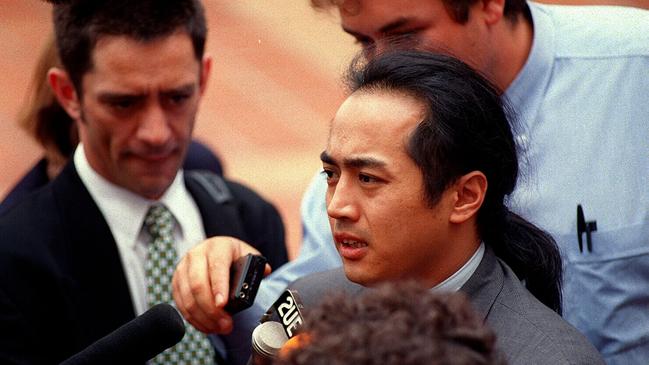

Controversial barrister admits he’s been a willing, sometimes overpaid player in the “pantomime” of Australian criminal law.

He asks if his book is lacking somehow and it lacks nothing but a kill switch. It lacks nothing but a red wire for a bomb disposal engineer to cut and shield the Australian criminal justice system from the flying debris of Andrew Boe’s words. He punches in combinations, hitting systems and individuals, lawyers and judges. Good title for his book: The Truth Hurts says a lot about a criminal defence lawyer and barrister reflecting on more than 30 years working inside a justice system he believes was broken from the start; a man confessing to the painful truth that he, too, has been a willing, well-paid and sometimes overpaid player in the “pantomime” of Australian criminal law. “My hands are hardly clean.”

He’s represented kid killers and serial killers, rapists and child sex offenders, public figures and politicians; helped to overturn convictions for the likes of Pauline Hanson. He’s seen what happens to indigenous Australians before the courts and he tells the story of the young man who haunts his quiet hours; the boy whose case he screwed up royally, the boy who taught Boe to be a better lawyer at the cost of that boy’s freedom. The story of Robyn Kina, an Aboriginal woman sentenced to life for fatally stabbing her partner with a kitchen knife, and Boe’s role in the groundbreaking 1993 appeal that won Kina’s freedom by highlighting woeful inadequacies in her initial defence and how it failed to convey – largely through a lack of cultural nuance and understanding – the horrors she endured at the hands of her partner who, amid years of gross abuse, tied her to a bed for three days, raping and beating her.

He tells of his scarring legal losses on Queensland’s Palm Island and the 2004 death in custody of Cameron Doomadgee. The unfolding story of a more recent case: the death of Kumanjayi Walker, a 19-year-old indigenous man fatally shot at his home in Yuendumu, 300km from Alice Springs, on the night of November 9, 2019. A Northern Territory police officer has been charged with murder over the shooting. “It’ll change the course of history for black people,” Otto Jungarrayi Sims, an elder from Walker’s Warlpiri community, told The New York Times. “There is hope,” he said. No small portion of which rests upon the shoulders of Andrew Boe.

By invitation of Walker’s family and friends he has again landed himself, reluctantly and cautiously, smack-bang in the blood-red centre of a moral, political and legal firestorm with far less to gain than he fears he could lose, starting with faith in his profession and ending with faith in his country. But into the brief he dives because he can’t help himself. Such is the ongoing story of Boe’s extraordinary, contradictory, revelatory life.

No, nothing lacking in the book. But there might be one thing missing from the narrative. “You left out the cave story?” I say.

The story of an old woman he met in a cave at the top of a mountain. The old woman who saw his future and gave the troubled lawyer the answers he needed. Boe smiles across an office desk filled with legal papers and briefs. He calls that cave story “esoteric”. Relevant only to a select few. “I don’t want this conversation to be distracted by the esoteric feelings that we have about stuff,” he says. “When you spend too much time introspectively looking at things that have happened to you, you start convincing and deluding yourself that it was somehow remarkable.”

His book is painstakingly built on matters of fact that are deeply relevant to every Australian alive in 2020. The cave story is built on possibility and relevant only to him. But the cave story is most assuredly remarkable.

It was 1994, the same harrowing year in which hisbeloved father was slowly dying and an exhausted Andrew Boe would wake up in a prison cell resting his head on the shoulder of a client named Ivan Milat. Boe was on a pilgrimage of sorts to Burma (Myanmar), the homeland from which his family had fled to Brisbane when he was only four years old. He was running away. He’d left his then wife, Jacqui Payne – now a Queensland magistrate and one of the two women in the world who know and love him best. His life was reaching overload. The naive law clerk in his 20s had risen to rock-star lawyer in his 30s. A colourful new-guard, brown-skinned, gum-chewing, ponytailed tearaway upsetting the scales of justice inside the stoic and grey Queensland legal establishment. Defender of robbers and rogues and rapists, but a champion of the underclass, too, and a relentless protector of process and the presumption of innocence. Designer suit. Porsche 911. Truth before consequence. Swag before silk. Smells like Burmese spirit.

“He wanted to stand out and, of course, he did,” says Margaret McMurdo, retired judge and former president of the Queensland Court of Appeal. “He wasn’t white. He had a swagger and confidence about him and he drove some flash car that he probably couldn’t afford. But what also stood out was his courage. He was prepared to take on cases for the underdog, for the indigenous. And his courage was what some judges wouldn’t have liked about him. It was a kind of crazy courage that wasn’t always measured.”

On that Burma pilgrimage Boe woke at dawn one morning and, with several of his cousins, hiked to the summit of Mount Kyaiktiyo, one of the three most sacred spiritual sites in the country. Atop this mountain is a huge golden rock – wrapped in gold leaf contributions from pilgrims who come from across the world – that balances in apparent defiance of the laws of gravity on the edge of a 1100m-high precipice. At the summit, Boe followed a young cousin nicknamed Duck Egg through a narrow and claustrophobic tunnel until they spilt into the candlelit cave of a small and mystical woman surrounded by pilgrims kneeling and praying at her feet. The woman looked directly at Boe – through him – and summoned the hotshot lawyer to her side.

The cave woman held his palms and began to speak and with her words the pilgrims inside the cave began to weep and wail in great pain and sorrow. Boe knew some Burmese but not enough to understand her. He asked his young cousin to translate and he did so reluctantly. “Your father is dying and will die very soon,” Duck Egg said, softly. The cave woman spoke some more and Duck Egg translated: “There are reasons why he took you from here. You will be an advocate for the little people. There are some cases in which only you will be able to prevail over injustices.”

Then the cave mystic said something else that made her kneeling pilgrims wail louder, cry harder. Boe turned to his cousin and Duck Egg spoke slowly and nervously, burdened by the weight of bad news. “You too will die young,” he said.

He seems to wear each case he has fought on his face and in his eyes. Each bloody and sickening case seems to have gouged something from his insides, stolen something from his soul. Parents bury their murdered children in the backyard then settle in for a backyard Christmas piss-up; a man violently sodomises his wife then locks her in a room because she has the temerity to bleed. The big cases have wearied him, wilted him.

He thought the Doomadgee case could have changed things for indigenous legal representation in Australia but it only dragged him deeper into the swamp, so deep he nearly drowned there. Cameron Doomadgee died in a police cell on Palm Island, north Queensland, in November 2004. His autopsy found his liver had been almost cleaved in two by force applied to his abdomen, prompting violent riots across the island. The post-mortem pathologist compared Doomadgee’s injuries to those of a plane-crash victim. His arresting officer, Senior Sergeant Chris Hurley, was later acquitted of manslaughter and the wounds of that case have not healed for the residents of Palm Island and for their most high-profile legal representative. “I felt that I had fought the good fight,” Boe says. “But not to put too fine a point on it, I was f..ked.”

He turns in a swivel chair at a desk in the high tower office of his chambers in George Street, Brisbane, and looks through a wall-sized window across a blue-sky cityscape that stretches beyond his great beginning. The working-class, multicultural suburb of Buranda on Brisbane’s bustling inner southside, where his migrant family landed in 1969. His father, U Shan Boe, was a successful newspaper publisher in Burma before he fled with his wife, Daw Khin Khin Nu, and their five sons. In Brisbane, U Shan was forced to take menial jobs to feed and educate his boys. Restaurant kitchen jobs. A job in a cement-bag factory. In a small kitchen in a cheap house he cooked his family Burmese dishes like minced mackerel in pungent curry soup and he spoke of potential and hope and how every last nugget of pride that he’d had to swallow in fleeing to Australia would be coughed up as diamonds if it meant seeing his sons swivel in their expensive chairs one fine day in the kind of plush office space that Boe swivels in now.

“He was a first-generation migrant who understood our community better than a lot of multi-generational Aussies,” former Supreme Court judge James Thomas says of Andrew Boe.

Margaret McMurdo paints a picture of a young lawyer always punching above his weight, a rogue salmon always swimming upstream with arguments that challenged a century of legal thinking; a maddening intensity and length to his footnotes on legal submissions that infuriated judges. “On one hand it’s unethical to put forward unarguable arguments, but on the other hand the law has to develop and common law is a growing, developing thing,” McMurdo says. “If he would make submissions saying that the courts should go one way when all of law is going the other way, that would get judges pretty angry. But I was sorry to see him gradually move out of Queensland. Even though you wouldn’t want a whole legal profession full of Andrew Boes, gee, it’s good to have a few of them because they do help challenge and develop the law.”

Boe takes a deep breath and looks at the ticking time bomb resting on his desk, his soon-to-be-released 300-page “exposé of imperfect justice”. He wears a black flat cap. Black scarf. Black shoes. Black shirt. Black ink on the bicep hidden beneath that shirt. Tattooed words in Burmese: “Freedom from fear”. Black ink through his book, wired with over 30 years of microscopic observations from the legal coal face. “I’m glad it’s off my chest,” he says.

The truth hurts and here’s the central truth to his book: Australia’s criminal justice system was not designed to seek the truth. It is a system designed by long-dead men for a long-gone world. Adversarial. Exploitable. Filled with criminal cases that fail the fairness test before they even start. Judges and juries forced to dig for truths only inside the mounds of permitted evidence presented to them when mountains of evidence remain unseen. Livelihoods not hanging in the balance of justice but in the ability of a lawyer to spot a hole in a brief; the ability to afford a lawyer who can spot that hole. The pendulum of human fate swinging between the hidden prejudices of judges, witnesses, jurors and lawyers. Little room and less money to accommodate language barriers, traditional practices and practical realities. Increasingly politicised and underfunded legal aid and Aboriginal legal services that are so inadequate that for most indigenous and indigent accused, Boe says, “the choice will increasingly be between being unrepresented or being represented badly”. The left and the right and the woke and the lip-service catchcries – “It’s a national shame” – over indigenous prison rates and deaths in custody but the glacier of real change moving too slowly, if at all. Slick young lawyers too rarely willing to admit their mistakes, much less learn from them. Non-English-speaking indigenous defendants represented by ambitious but shallow young lawyers ticking the box on their “indigenous experience” with a season or two in community court but never returning to communities in their 40s and 50s when they’re finally useful. Entrenched and guarded judges whose histories of one-on-one communication with indigenous Australians could be summed up in a single sentence: “I sentence you to 10 years in prison.”

But don’t get him started on judges. Most barristers would save their public judging of the judges for retirement. In the book Boe paints some judges as calculating and “driven by self-importance”. Some, he writes wryly, “find that the cold Australian winters are best spent educating themselves in the Northern Hemisphere”. He calls them “try-ons” today. Is he not concerned about courtroom retribution? “The judges that get it will not be distressed but the judges that don’t will be extremely harassed by some of the things I’ve said in the book,” he says. “Seriously, to say, ‘OK, we’re now judges, we have tenure, we can get everything we do wrong but our system corrects it on appeal and nobody can ever remove me’?

“If you were given that privilege, wouldn’t you check your face every morning and say, ‘How the f..k did I get this? How lucky did I get?’ And how much equanimity would you then possess when going out to judge people? Wouldn’t you just be a little bit more reasonable about the things that you disagree with and allow the litigants to bring their differences to you in an appropriate fashion and then resolve them as best you can? You would exercise your judgment and discretion. But some judges aren’t like that. Some judges are conceited know-it-alls who will sit there and castigate one side because it doesn’t conform to their view of things and then spend all their time bathing in their sense of power in these little rooms.”

A message lands in Boe’s phone. From Sydney, where he lives with his partner, filmmaker Samantha Lang, and her two daughters. There’s a family chat group he shares with Samantha and his ex-wife Jacqui Payne, the youngest daughter of an Irishman and a Butchulla woman from what is now called Fraser Island, and the six children they raised together. If there are defining moments in the shaping of Boe’s career, meeting Payne was a big and early one. When she reflects on Boe’s life for the past 40 years – every self-doubt, every perceived failing, every success – Payne begins to cry. “Sorry, that’s part of my personality,” she says on the phone from Kowanyama on Cape York Peninsula, where she’s presiding over a series of difficult cases. “What it is with Andrew – and yes, we were married and have six children, including four birth children – [is that] mostly I’m proud of him.

“How do we as a society treat our most disadvantaged, our most unpopular and our most despised? Each of the stories in that book represents long and hard work. Herculean effort. Many of those cases he acted pro-bono or was lowly paid. He’s a lawyer, remember, and what he sells is time.

“I remember when Andrew was asked to look at the Robyn Kina case. We were married at the time. We had small children. The work Andrew did in that time kept him away for long hours. I was a lawyer myself with my own law firm but family life was left to me and Andrew would work those long hours and I may have said something about me being left with the family responsibilities… I remember Andrew wanting to comfort me in some way and he said, ‘Robyn’s matter will end’, and I remember saying, ‘There will always be another Robyn Kina’. And that’s exactly what his life has been. Human stories that needed the kind of attention that Andrew was willing to give.”

Too willing sometimes, says Samantha Lang. If there’s a chink she’s spotted in Boe’s legal armour it’s the fact that he keeps forgetting there’s a whole nation of people who also want to solve the problems within Australian criminal justice. “He’s not alone,” Lang says. “It’s up to all of us. We all have a responsibility in this. But when you’re inside these situations, it’s easy to feel that it is all on you.”

She’s been with Boe for 11 years. The first six were spent living in separate cities, before bringing their children together to form what Lang describes as a complex, sometimes tough and always enriching “Brady Bunch”. She met Boe at an exhibition of photographic portraits by a mutual friend. Over dinner that night, Lang thought he seemed too serious for conversation, too intense; still recovering from the losses of Palm Island. Angry. At the dinner guests. At their conversations. At their world. The first words he uttered to Lang were delivered without a hint of humour across the dinner table: “So, what do you do with your privilege?”

“But the very beginning of my love for him was really because he was very kind to me at a time when I was at my lowest ebb,” she says. “And that kindness was very surprising. At the time we met, we were probably quite broken… but that is what he’s very good at. In a bizarre and perverse way, that is when he is in his safe space and when he is most potent. He has this capacity for people in crisis. He has a capacity to be empathetic to their situation and, in some ways, normal life is harder for him. That’s sometimes tricky to live with.

“I encouraged him to write the book because he was one of the few lawyers of colour in Brisbane in the 1990s and he got an outsider’s view on the inside of justice and I think it was really important that he gave voice to that. But, also, I would hear these cases and I would feel the emotion of them and I thought, ‘How on Earth is he even able to cope with all this?’ I could see what he was going through and I thought, ‘Man, this is going to be impossible to live with, he’s got to get this stuff out’.”

When Boe was six years old his father went to prison for 18 months. He remembers visiting his father in Brisbane’s Boggo Road jail and he remembers how scarred his father was by the experience. His father never spoke about why he was put away. And then he died. The old woman at the top of the mountain was right. He died of lung cancer at the age of 69. Old enough, some might say, but far too young for the many who loved him.

Boe later pieced together something of the story of his father’s imprisonment. A white-collar crime that Boe seems reluctant to bring his renowned investigative eye to. “I do know that he denied his guilt until the day he died,” he says. “I now know enough about what the system must have been like for a Burmese defendant in front of the jury, and I wasn’t willing to make an assessment of whether he did or did not do what he did.

“When I became a lawyer it may have been the right time for him to come and talk to me about it if he wanted to, knowing that I would probably understand what the process might’ve been like. But I guess we just ran out of time.”

Some weep for months over lost parents. Some drown their sorrows in drink. Andrew Boe drowned himself in the criminal defence of Ivan Milat, the infamous “Backpacker Murderer” who brutally killed seven young people in NSW between 1989 and 1993. “I was obviously devastated and I didn’t function for a long time when my father died … but it’s a lot easier sometimes to say, ‘Well, this is important, so the rest of it can wait’. If I was looking after my mental and emotional self, the last thing I should’ve been doing is ignoring the death of my father.” Boe worked 20-hour days, seven days a week on that case; exhausting himself to the point where he fell asleep inside Milat’s cell during a pre-court meeting, his head resting on the shoulder of a surprisingly accommodating killer. “He was holding me like a baby,” Boe says. “Falling asleep on his shoulder was falling asleep on a human being.”

It was Boe’s job to ensure that that human being, no matter how heinous his crimes, got a fair trial. “It then came to me that how I could justify my involvement to myself was that I was going to make sure that, no matter what he had done, the system was going to be as fair as it could be on my watch… he would get the best legal team I could assemble, the best framework, and we would have the best capacity to give him his chance of putting his case to the jury. And, because he was so much already found to be guilty by the media, then it was the best example of a case that defence lawyers should do to profoundly believe in the system.”

He sees the other side: “The paradox of striving for systemic fairness while representing people involved in the most obscene acts of human misbehaviour does not escape me, and those cases have had an effect on me.” He admits to disliking a great many of the people he has represented, and observes this of Milat: “I don’t think anybody has been more respectful, professional and polite to me than Milat. He would call me ‘Mr Boe’ for the first six months that I knew him, and even then he felt uncomfortable calling me by my first name.”

Noble philosophies of criminal law aside, Boe knows it was partly his ego that drew him to the Milat case. “I mistook attention for respect,” he says. “For an assessment of my abilities.” He shakes his head, thinking of his younger self. “Man, I went to my first interview to be a law clerk wearing a white cotton suit. I peacocked my way right through my early career. I had to pull it up. I was becoming a personality before I was even a person.”

“You too will die young,” said the old woman in the cave at the top of the mountain. He’s 55 now and maybe a version of her prophecy has indeed come to pass. A version of himself did die young. The brash version of Andrew Boe. The ego monster version. Born in his place was a man who appears not the least bit free from fear, from failure, and he’s better, wiser because of it. Ego is a clever monster. It could trick a lawyer into believing the impossible. It could even make a lawyer believe that the future for indigenous Australians in the criminal justice system rested upon his shoulders alone.

“There are some cases in which only you will be able to prevail over injustices,” the cave woman said. Only you, Mr Boe, and you alone.

“As a 20-something lawyer I thought I could disrupt the system on my own,” he says. “As a 30-year-old I failed dismally to strike the right balance between family and work. As a 40-year-old I felt so let down by systemic imperfections as to almost throw in the towel.” As a 55-year-old he’s asking for help from his children. When he was asked to work on the Kumanjayi Walker case the first people he turned to were his youngest kids, the ones who will suffer most from his absence through a case that’ll take years to unfold. “Should I do this?” he asked. “Dad, you have to do this,” they replied.

He flew into the Northern Territory to work the matter – a preliminary court mention is scheduled for August 14 – with his eldest daughter, Greer, by his side. She’s a gifted young lawyer with a passion for restorative justice and indigenous rights. She lights her father up. She lights his old legal fires on the days when he’s sure they’ll blow out for good. She gives him hope. In 2020, the world wants Greer Boe working in court. “Young, Asian, indigenous, female, educated,” Boe smiles. “Her voice is being heard now. She can decide what to do with it.”

The Walker matter is already proving taxing. Indigenous cultural issues. Media pressures. Political issues. Police union pressures. “We haven’t even gotten into f..king day one,” he sighs. But into the swamp he dives, clinging to the life raft of his hope and his children and three beautiful words that Samantha keeps repeating in the quiet hours. You’re not alone. You’re not alone. You’re not alone.

The Truth Hurts (Hachette, $32.99) is out Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout