Malcolm Gladwell on Covid, cancel culture and The Bomber Mafia

Malcolm Gladwell on Covid, cancel culture and The Bomber Mafia.

There aren’t many things likely to distract you during a conversation with Malcolm Gladwell: the author is a veritable blizzard of curious facts, surprising anecdotes and flailing arms. But I find myself distracted nonetheless, because on the wall of his office in New York is a giant picture of Chairman Mao. Dressed in his signature grey suit and gently smirking, the murderous dictator hovers menacingly over the 57-year-old’s right shoulder.

Gladwell finds the poster hilarious, explaining that he bought it at a garage sale 15 years ago and rediscovered it in a cupboard recently. “I thought how fun it would be, while transacting business at my desk, to have Mao visible over my shoulder,” he explains. “The idea of having this truly despicable tyrant reminding me of the importance of being human while I work – I thought that was good.” There’s Gladwell for you: quirky, offbeat and a master of surprise.

We meet via Zoom, me in a gloomy Manhattan hotel room, him in his sunlit office. Gladwell’s face looms alarmingly close to the screen each time he is feeling emphatic. He has the air of an overzealous children’s party entertainer but it’s all strangely infectious. Even if you don’t love his “smart thinking” schtick, which has spawned an entire industry of offshoots and imitators, it’s impossible to be bored in this man’s company.

These are the qualities that have powered his extraordinary career, spanning 25 years at The New Yorker, six best-selling books and now a podcast empire anchored by his show Revisionist History, which takes alternative glimpses at all manner of issues such as why the desegregation of American education had unexpected downsides and the difference between Israeli and American chutzpah (you might have to listen to that one). It’s no exaggeration to call Gladwell the most famous intellectual in America: that rarest of eggheads who is able penetrate the Christmas stocking market. Many prominent wonks criticise him for his tendency to simplify science into airport wisdom, yet the books that made him famous – The Tipping Point, Outliers and Blink – thrive not because of their stunning originality, but because he takes dry academic research and weaves it into compelling narratives.

Gladwell’s most famous theory, the “10,000 hours rule”, which argued that it takes roughly 10,000 hours to master a given field, has been regularly debunked. “Malcolm Gladwell is America’s best-paid fairytale writer” was how The New Republic headlined a review of David and Goliath, his 2013 book about how underdogs triumph against the odds. One reviewer in Esquire even invented a name for Gladwell’s technique: the “Gladwell feint”, which is when an author questions an obvious assumption about the world, tells the reader they have it all wrong and then flatters their vanity by suggesting they subconsciously knew the real answer all along.

“It doesn’t really bother me,” Gladwell says of the criticism. “It’s all about your goal. If you’re a professor of English literature at Oxford, writing an academic book that culminates a lifetime of research, you had better not cherrypick and simplify.” His audience, however, is very different. He’s aiming to reach “13-year-olds”, “rich Republicans in Texas” or the person who reads only two books a year. They choose his work, he believes, because it is fun and accessible, exposing them to ideas they might not otherwise encounter. “That same academic who is critical of me: I’m not critical of them. I worship them.” After all, he points out modestly, Jesus also taught largely in parables. “Jesus has one famous sermon, the Sermon on the Mount. The rest is elliptical stories that he wants you to think through on your own.”

Ever the optimist, Gladwell is eager to see the potential upside amid the woes of the pandemic. He’s hoping that if the exodus from cities such as London and New York continues, property prices will fall, allowing more “interesting” people to move back in. He also believes our recent experiences might have given us the tools we need to survive climate change. “It’s restored our faith in science,” he says. “It’s restored our faith in collective action. It’s reminded us that good government really matters and lousy government screws you up. We’re going to need all these three.”

He also thinks society has proven more resilient than many of us expected. “Tremendous loss of life, that was the expected part,” he says. “The unexpected part is we didn’t fold.” Gladwell segues on to the subject matter of his latest book, The Bomber Mafia – a history of bombing strategy in World War II – to illustrate his point. “Take the Blitz. Everyone thought it was going to lead to widespread panic, but it doesn’t. The opposite happens. It teaches people in the UK that they are much stronger than they realised. People dust themselves down and get on with their lives. They realise that war, as horrible as it is, is not a reason to run screaming into the woods. I think the pandemic has had a very similar effect on many people. Those who have survived have learnt that they’re more resilient than they imagined, that society is more resilient than they imagined.”

The Bomber Mafia tells the story of a group of cerebral US air force officers based at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, who developed a theory of precision bombing before and during World War II. According to this theory, bombers would hit selected targets – factories, command posts, supply lines – in order to prevent soldiers dying by the million over contested scraps of mud. Yet as the 19th-century Prussian general Helmuth von Moltke liked to say, no plan survives contact with the enemy. Even with new bombsights, even though they tried flying in daytime to improve accuracy (at dreadful cost), in the heat of battle the bombing simply wasn’t precise enough to hit specific targets. Eventually the Americans moved towards the British approach of “area bombing”, which carpeted target areas of key industrial cities, often heavily populated, to sap opposition morale and wreak general havoc. It was brutal and, some historians have argued, a war crime, but by 1944 such objections were for the birds.

The American switch in strategy took real force when General Haywood Hansell was replaced by General Curtis LeMay as head of 21st Bomber Command in Guam, the US launch pad for the aerial assault on Japan. Under pressure to bring Japan to its knees, LeMay led the firebombing campaign that used napalm to incinerate crowded wooden cities and claimed more lives than the atomic bomb attacks at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “Probably more persons lost their lives by fire at Tokyo in a six-hour period than at any time in the history of man,” Gladwell writes, estimating that the initial firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945 killed up to 100,000. Upon returning to Guam, pilots had to fumigate their planes to rid them of the smell of burning flesh.

Yet for all the horror, Gladwell doesn’t condemn the generals. “I’m sympathetic to the plight of decision-makers in that moment. By 1944 these air force guys are exhausted to their bones, they’ve lost dozens of colleagues and been through hell not for a week or a month, but for years. It’s difficult for me to pass judgment from my nicely appointed office in New York.”

The “Bomber Mafia” failed in their mission. Instead of saving millions of soldiers, aerial bombing during World War II multiplied the carnage, devastating civilian populations from London to Dresden to Tokyo. But while they lost the argument in the 1940s, their approach has finally won out – Hansell and his gang would be thrilled with today’s precision drone technology. “Drones represent an advance but not a victory,” Gladwell says. “The Bomber Mafia was correct that precision in bombing is a moral improvement, but it doesn’t solve any of your problems. If it makes it more likely for you to use bombs to solve a conflict, then it’s tricky.”

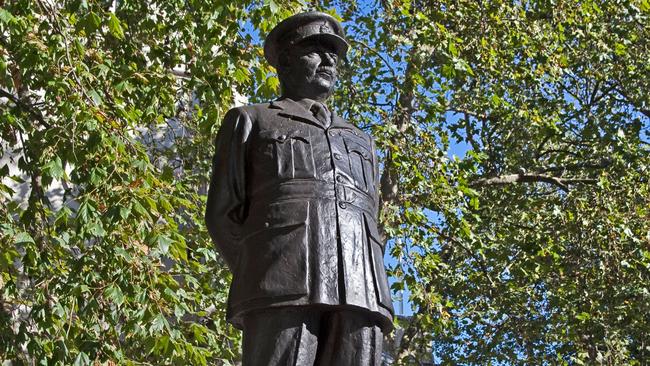

One person who receives a less sympathetic treatment from Gladwell is Arthur “Bomber” Harris, the British air chief who oversaw the RAF’s bombardment of Germany. “I think he was a psychopath,” says Gladwell bluntly. Harris was responsible for the flattening of Dresden in February 1945, which claimed 25,000 lives to achieve a military advantage that has been debated and questioned ever since. So perhaps Gladwell agrees with the campaign to take down his statue on the Strand in London? Absolutely not. “I get driven to distraction by the people who want to tear down statues,” he says. “We need more statues, not fewer. Let’s go crazy on the statues; they’re great opportunities to teach people history.” He proposes putting a statue of Harris’s most vehement critic, the nurse and pacifist Vera Brittain, next to the original. “You could have Brittain looking at Bomber Harris with as much venom and contempt as possible, because she thought he was a monster.”

This answer sums up what I find most interestingabout Gladwell. In the culture wars consuming American media and beyond right now, he doesn’t have a clear side. He is dual heritage, the son of a Jamaican woman who faced considerable prejudice when she married his white father in 1950s England. He writes thoughtfully on issues of race, segregation, policing and identity. He favours some form of reparations for slavery and he’s “incredibly encouraged” by the racial justice movement that has been turbocharged by the death of George Floyd. “The world has been run by white men for a long time,” he says. “We’re finally standing up and saying they should share.”

Yet Gladwell’s conservative Christian upbringing, his restless mind and his complex identity cause him to chafe against some of today’s ideologies. He’s sceptical about the legalisation of cannabis, for example, believing we don’t yet have all the facts. He’s also opposed to cancel culture, and adamantly pro free speech. “I feel like we’ve forgotten what it means to forgive people and be accepting of difference,” he says. His concern is about structural inequalities such as incarceration rates and educational disparities, not “matters of etiquette” such as the New York Times reporter Donald McNeil losing his job for using the N-word in a conversation about racism. “Let’s not get sidetracked with questions of individual conduct,” he argues. “We’re all imperfect, I think we knew that. Let’s just move on to more important issues.”

When I ask what still motivates him after all his success, he references a podcast episode he is making about the science of laundry detergent. “There are 1000 people in Cincinnati, PhDs, who spend their days trying to work out how to make Tide clean your clothes better, and I can go and hang out with them,” he enthuses. “Who doesn’t want to do that? I just find it all fun.” Sounds like a washout to me if I’m honest, but you just know millions will tune in.

The Bomber Mafia: A Story Set in War by Malcolm Gladwell (Allen Lane) is out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout