Louis Theroux on his audience with Tiger King Joe Exotic

Netflix’s real-life tale of big cats, oddball personalities and murder plots has the world gripped. Louis Theroux witnessed the madness first-hand.

For the past few weeks, the strange saga of a group of American big cat owners, told in a seven-part documentary called Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness, has been whatever the equivalent of a water-cooler talking point is in this Covid- racked world. The series has captivated viewers in the millions with its colourful cast of characters, vast menageries of animals, details of cult-like polyamorous domestic arrangements and, at its heart, not one but two possible murder-for-hire storylines.

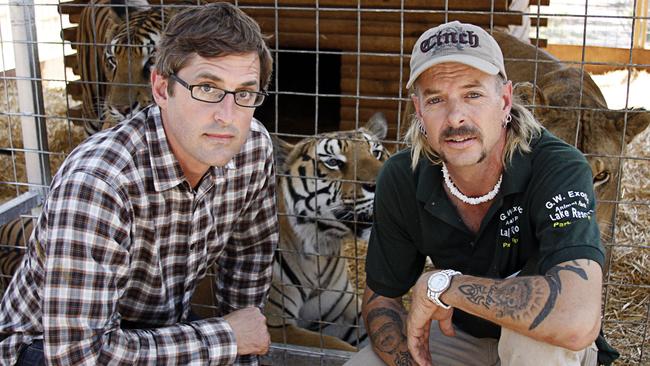

I too binge-watched the series over successive nights, marvelling at the weird twists, unexpected deaths and superabundance of exotic fauna. But Tiger King had an added interest for me. In 2011, I made a documentary about exotic pet owners in America. I know several of the key players in the series. In fact, over three separate trips, I spent the best part of a week with the Tiger King himself.

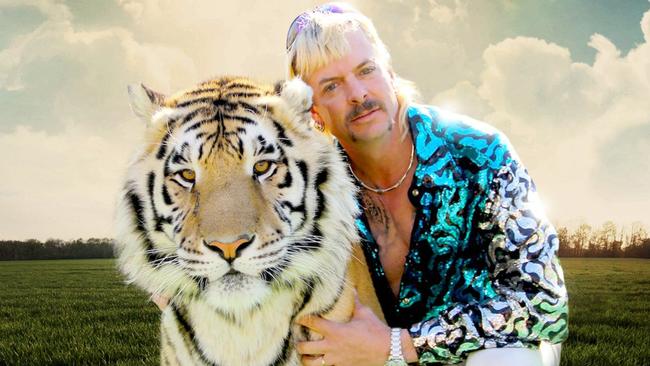

Joe Maldonado-Passage, born Schreibvogel, and known to most as Joe Exotic, is a skinny, high-voiced good oil’ boy with a dyed blond mullet, a row of rings in his ear, a couple more in his nipples and (so we are told) a “Prince Albert” in the end of his penis. Joe is one of those larger-than-life characters who screams “made for TV” and, indeed, seems to have dedicated much of his life to a continuous audition to play the lead in a reality series. Not content with running his zoo, he has a side-hustle as a country-and-western singer, complete with moody music videos. He has also been at various times a stage magician, a pet shop owner and a police officer, and is – through most of the series – the mainstay of a domestic arrangement with two much younger men, neither of whom, apparently, is gay.

When I met him, on a blustery May day in 2011, what stood out, apart from the blond mullet and the nervous energy, was the blue eyeliner tattooed on the rims under his eyes. He was a strange mix of butch and femme signifiers. He carried a gun, which never left his side, and handcuffs, but there were also the aforementioned piercings and an air of heightened emotion. He wore what appeared to be a police uniform, including sergeant’s stripes and a badge, which was very official-looking, except it read “animal rescue”. Evidently he still had some nostalgia for his time as an officer of the law – though what kind of cop he made was hard to imagine, other than a pretty odd one. Altogether, though, Joe struck me as likeable and friendly. I warmed to him, and his ridiculousness was endearing rather than annoying.

Joe’s zoo, the GW Exotic Animal Park, was just off Interstate 35 in south central Oklahoma, not far from the Texas border. It has been characterised over the years as a “roadside zoo” – the phrase suggests overcrowding and slack management – but the facility was more salubrious than I’d expected: large, basically clean and solidly built. That first encounter was memorable because we’d had word that a tornado was bearing down on the area – we were in the tornado belt in tornado season. The day before, a twister had ravaged the nearby town of Joplin, killing 158 people. Our first four or five hours of filming were taken up documenting the spectacle of Joe locking down his cages and us all contemplating the possibility that freak weather might be about to set loose 200 semi-tame tigers – and 1200-odd other animals – on the townsfolk of nearby Wynnewood.

In the event, the tornado passed us by, but an atmosphere of incipient catastrophe never quite let up the whole time I was with Joe. He seemed to lurch from crisis to crisis, constantly on the verge of financial ruin, handling low-level bites and maulings, and being hounded by “animal rights people”, as he put it. Joe was a figure of notoriety even back in 2011. He had been the subject of undercover filming by animal rights group Peta in 2006. He was in these people’s crosshairs for many reasons: his alleged mistreatment of the animals in his care; just the fact of having all those animals; but above all for his practice of breeding tigers.

Breeding is the defining hypocrisy of a certain kind of animal sanctuary. Sanctuaries notionally exist to provide homes for creatures that need them, not to breed new ones. But it was also the case that one of the few dependable ways for outfits such as Joe’s to make money was to charge large sums for people, usually children, to take photos with tiger cubs. He did this at his park and also in a roadshow that travelled around malls in the ever-decreasing number of states in which the practice was not yet banned.

Though his facility was a non-profit, Joe had high overheads: a lot of tiger and lion-sized mouths to feed, not to mention water and electricity bills and staff costs. The flaw in this strategy – leaving aside the ethical issues involved in taking tiger cubs from their mothers on their first day of life and trucking them around suburban parking lots to be cuddled by children for photos – was not hard to spot. Those tiger cubs were money-makers for a matter of months. There then followed another 20 years of life, during which they would become aggressive to the point of potentially killing any human within pouncing distance. At Joe’s facility, they joined the vast number of surplus beasts in cages at the back of the property, consuming cast-off cuts of meat donated by Walmart.

Joe had about 150 tigers back then, though I have no idea how many of them were grown-up “photo babies”. Still, as awful as the practice is, and despite the many compromises and cruelties entailed in Joe’s running of the GW zoo, it was hard to dislike the man himself, maybe because he seemed neither to be hiding many of his misdeeds nor to take himself too seriously, not to mention that his emotional volatility – laughter, tears, kindness, paranoia, all in quick succession – inclined me to be a little protective of him.

Joe’s emotional frailties, combined with his flamboyance, may also help explain his apparent romantic success. In Tiger King we see him married to two much younger men, both quite good-looking, though one of them, John Finlay, is somewhat lacking in teeth. When I knew Joe he was also in a three-way domestic arrangement with John and a third person, Paul, who was in his 20s. In the film we made only a brief mention of Joe’s love life, in a scene in Joe’s kitchen in which he explained, regarding jealousy, that love-making only happened with all three involved. “It works awesome,” he said, then laughed and added: “Because we’re all too tired to have sex.”

Soon after, we were bottle-feeding Joe’s latest white tiger cub. “I fed him from the minute he was still wet,” Joe said, pulling the tiny tiger from a fold-up cot. “Would it make more sense to prioritise preserving habitats in the wild?” I asked. “There’s people working on that,” Joe said airily, “but unfortunately we have more powers higher than us destroying the habitat.” Joe’s house seemed always to be full of mewling cubs. One of the most affecting scenes in the Netflix series shows him dragging a newborn cub out of a cage, then complaining that he can’t sleep for the noise it makes.

And yet for all his questionable qualities, Joe was far from the only – or even the strangest – oddity I met in the exotic animal world in 2011. On a second filming trip, while at Joe’s zoo for a “wild animal expo” and “monkey banquet”, a fundraising dinner at a local convention room, I ran into another future cast member, Tim Stark. Though they were friends, Tim was cut from different cloth to Joe. Where Joe’s style could be called hillbilly razzmatazz, Tim affected a kind of Vietnam vet chic, decked out in camo, head shaved, with a handlebar moustache. His exotic animals seemed an extension of a certain attitude of unapologetic masculinity. When I visited him, within a few short hours in front of the cameras he’d got into a punch-up with a bobcat, tussled with a white tiger on a leash in a rainstorm and garlanded me with a pungent 22kg baboon with an alarmingly protuberant butthole called Tatiana (the animal, not the butthole), who seemed to take a shine to me, picking hairs from my neck and, at Tim’s prompting, soliciting a kiss.

Tim had a weird theory that encapsulates the attitude of many exotic animal owners. He had just climbed into an enclosure with a pair of grizzly bears called Obadiah and Eli. I’d noticed the bears had been pacing neurotically, showing signs of the stereotypical caged behaviour sometimes termed “zoochosis”. “What about people who say, ‘These are wild animals, you are going against their intrinsic nature by penning them up’?” I asked. “The reason they have that natural territory out in the wild is not because that animal chooses to travel that distance,” Tim replied. “That animal has to travel that distance.” He cited the example of bears in national parks hanging around humans for free food – “beggar bears”. “Their natural instinct is to survive, but they’d much rather survive by having food handed to them,” Tim said. “They’re not stupid.” The strangeness of imagining that a bear’s needs might be met simply by providing food – not stimulation, not space, not freedom – left me momentarily speechless.

Much of Tiger King deals with the feud between Joe and Carole Baskin, another self-styled big cat protector and proprietor, along with her goofy-looking husband, Howard. Carole’s facility, near Tampa, Florida, is called Big Cat Rescue. It does not breed and, in fact, Carole had campaigned for years against Joe’s cub photo roadshow, persuading some states to outlaw the practice. In the series, Joe accuses Carole of hypocrisy – evidently, she had been a breeder – though the real issue for Joe, one suspects, is the effect the bans are having on his bottom line.

Joe’s grudge against Carole preoccupied him when we filmed. He would rant about her, mentioning his belief that she’d had one of her husbands killed. Tiger King spends the best part of an episode digging into the allegation that Carole murdered – or arranged the murder of – the husband, before (allegedly) putting him through a meat grinder and feeding him to her animals; or possibly (in Joe’s view) just throwing the body into the enclosure to be chomped up, bones and all.

In the series, the allegation of her misdeeds is thrown together with Carole’s various fashion crimes involving leopard print. She moons around her refuge in slow motion and one draws the conclusion, perhaps unfairly, that whether or not she killed her husband there is something not quite right about someone who makes a living out of providing room and board for a relatively small number of rescued animals while wearing flowerchild accoutrements in late middle age.

I should confess here that I greatly enjoyed Tiger King, my pleasure only slightly attenuated by a sense of envy and missed opportunity that I wasn’t involved in what has turned out to be a global smash. I do recall that, having made our documentary, which came out as America’s Most Dangerous Pets, I felt there was probably some kind of longer-form series to be made about that world, though I had no idea Joe would end up caught up in a murder-for-hire case. I really can’t claim any kind of prescience other than noticing that it is pretty weird for Americans to be keeping multitudes of large exotic animals in small cages.

Among other things, the pathologies on display in Tiger King are symptoms of a condition known as “living in Oklahoma” – a state that ranks 46th in America for healthcare. The backdrop to the Joe Exotic sections of Tiger King is a community brought low by reduced opportunity, rampant meth and opioid use, and high incarceration rates. Many of Joe’s volunteers had a whiff of desperation about them: waifs and strays getting by on tiny wages and the free room and board. With facial piercings and expressions of bewilderment, they would wander about the zoo like kids on their gap year, waiting for someone to tell them what to do. One of the more touching scenes shows a desperate woman at a bus station weeping because Joe has offered her a place to stay.

If I have a quibble with the series, or maybe a cautionary note, it’s that the carnival of human folly it depicts should not blind us to the pressing, and less amusing, animal issues at its heart: playthings of a more powerful predator, kept in captivity because of human acquisitiveness, ostentation and control. In the name of preservation of species, many of the owners I met paid scant regard to actual safeguarding of habitats. “The wild?” they would say. “There’s no ‘wild’ left.” Meanwhile, the animals they ostensibly protected and fed and kept penned up were pale simulacra of the real thing. Hand-raised tigers are something closer to living taxidermy: deprived of their tiger nature, incapable of surviving outside captivity, living out their days in a state of enforced dependency.

I have written so far mainly about tigers. Though not touched on in Tiger King, the issues around primate captivity – melancholy apes, demented chimpanzees – are if anything even more troubling, involving as they do creatures of higher intelligence and longer lifespan that are more prone to frustration, lack of stimulation and mental illness.

Now – spoiler alert – Joe is behind bars, in a cell that is probably smaller than those he provided for his tigers. At trial he was given 22 years, having been convicted on two counts of murder-for-hire and some animal abuse offences. As I write, he is said to be in isolation with Covid-19, brought low, ironically, by a creature many times smaller and much less physically impressive than a tiger, but altogether more deadly.

Apparently he hasn’t yet seen the Netflix series, but is said to be pleased by all the attention. At the same time, word comes that the missing person case of Carole Baskin’s husband is being reopened. She is not named as a suspect, but it is not out of the question that Baskin too may one day be confined to a cage, though, to be honest, the prospect seems remote. I can’t speak for the 200-plus tigers that were at Joe’s zoo, but it is a safe bet that if they aren’t dead they are in a small cage somewhere, utterly oblivious to their new-found fame.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout