Live export trade fights back

Footage of dead and dying sheep en route to the Middle East sparked calls for a ban. But live animal exporters are fighting back.

In searing summer heat on an Australian sheep ship bound for the Middle East, horrific scenes were unfolding that would scandalise viewers who watched them on their TV screens. Video footage showed deckloads of sheep panting from heat stress, decomposing carcasses caked in a slurry of faeces and urine, and lambs lying dead, their heads turned upward for air. About 2400 sheep died on a single livestock ship, the Awassi Express, during an August 2017 voyage. Footage from four other voyages had also been captured by a whistleblower — in one scene, a sheep was thrown overboard while clearly alive.

The footage was like a guillotine blade descending on the neck of West Australian firm Emanuel Exports, the nation’s largest and oldest livestock exporter, which was responsible for the welfare of the sheep on the Awassi Express and the four other voyages. Within days of the scenes airing on 60 Minutes last April, animal activists holding placards and calling for a ban on live animal exports had assembled outside Emanuel’s office in Perth’s CBD. The protesters’ fury soon echoed around the nation, prompting federal Agriculture Minister David Littleproud to fly to Perth to front the media outside a cafe about a kilometre from Emanuel’s headquarters where his departmental staff were seeking answers from its beleaguered directors.

Visibly annoyed, Littleproud said it was important to “eyeball” WA farmers. Their futures were at risk if the trade, which sources 85 per cent of all Australia’s exported live sheep from the state, was not cleaned up. He announced a “short, sharp” review of livestock exports and signalled tougher penalties for exporters found doing the wrong thing. “You’re a cancer and we’re going to cut you out and remove you out of the industry,” he said. “Company directors need to be on the hook for this, not just in a financial sense but in a jail sense.”

Emanuel Exports and its head, Graham Daws, were nowhere in sight. Calls from the media went unanswered. It was left to the Australian Livestock Exporters’ Council to convey the message that the company was sorry, and to offer excuses. The sheep had been victims of “unique summer conditions” and “geopolitical tension” that had forced the ship’s captain to deviate from the cooler port of Kuwait City at the top of the Gulf to the hotter, more humid port of Doha in Qatar, where the sheep began dying within hours.

When I visited Emanuel Exports’ corporate offices for comment on that day, the lift to the fourth floor was locked. The family company, founded in 1955 by patriarch Tom Daws and spanning three generations, was under siege.

Almost one year later, the lift door opens freely onto the fourth floor and I’m invited into the managing director’s office. Behind the desk vacated by Tom’s son Graham Daws in the wake of the Awassi scandal is Graham’s 40-year-old son, Nick, who admits his family had no clue how to handle the crisis at the time. “Obviously seeing that footage was very distressing and completely unacceptable,” he says, adding that the deadly mix of heat and humidity that cooked the sheep “happened quickly over about three to six hours”.

“It was very hard on me and dad,” he says. “I’d never seen anything like that before.” How is that possible, I ask, when there are records of previous mass deaths — 3000 on one ship alone — in similar circumstances on livestock ships hired and stocked by Emanuel? “It had happened before,” Daws concedes, “but I’d never seen footage like that before.” So he was naive, ignorant? “Yep, yep, and what was being reported back to us obviously wasn’t reflective of what was happening.”

Four months after the Awassi footage was aired, Emanuel’s licence to export sheep was cancelled by Littleproud’s industry regulator. It was a devastating blow to a company that, in 2017 alone, had purchased and exported 1,384,860 sheep, representing 71 per cent of all sheep exported that year from Australia. Daws says he has spent part of every parliamentary sitting week in Canberra since then, pleading Emanuel’s case for a return of its licence. He won’t discuss the threat to Emanuel of criminal investigations into its treatment of animals that “are ongoing”, according to Department of Agriculture deputy secretary Malcolm Thompson. One of Thompson’s staffers told a Senate estimates committee in February that a “brief of evidence” relating to the Awassi voyage has been submitted to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions.

“We have not been charged with anything,” says Daws, who won’t discuss Emanuel’s appeal against its licence cancellation, currently before the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

Given all of this, most would expect Emanuel’s reputation to be rock-bottom among farmers and the wider livestock export industry, whose futures the company imperilled. Public aversion to the Awassi footage may be used by Labor, if it wins office, to justify acting on a promise to phase out live exports within five years. A ban has already come perilously close. A private member’s bill to stop the trade passed the Senate in September but failed by two votes in the lower house when Liberals Sussan Ley and Sarah Henderson, who strongly favour phasing out live exports, decided to give the industry another chance.

And that’s precisely what Emanuel Exports has been given. It should be a pariah, yet its star has risen even higher in WA; at agricultural shows and in saleyard huddles of farmers, it is even being hailed as the trade’s unlikely saviour.

In February, Emanuel Exports launched The Sheep Collective, a PR campaign with an upbeat website that describes it as “selling animal welfare to the world”. “We are only successful if we deliver healthy sheep,” the site states. “Good welfare is at the core of The Sheep Collective because it’s the right thing to do and it’s also good business.”

If it all seems rather hypocritical coming from the company that lost its export licence and brought the industry to its knees, Nick Daws doesn’t see it that way. Nor does Holly Ludeman, the forthright, smiling young woman he reached out to in the midst of the crisis. Daws first met Ludeman, a qualified vet with livestock industry experience, at a sheep feedlot a few years ago when they were both on an industry tour to Kuwait, the main Middle East customer for Emanuel’s live sheep. He explains that, as he stepped into his father’s shoes, he invited Ludeman to join him in restoring the company’s fortunes as its compliance officer. “I wanted her to launch a campaign of transparency, to restore faith in the industry.”

Ludeman says she wasn’t initially convinced. “I told Nick, ‘You may think you’re trialling me for three months, but I’m trialling you. If I don’t think you’re genuine, I’ll walk.’” Yet she is quick to defend the industry, pointing out that the death rate on the Awassi Express was “less than three per cent, and most of the sheep were discharged live”. “Livestock export is not glamorous,” she says. “It can be dirty, dusty and smelly, but it’s not cruel.”

Her first act was to sign up as an observer on two sheep voyages run by another exporter to see all aspects of the supply chain. “We needed to change the hearts and minds of Australians,” she explains. “We were never going to be able to talk to the activists against the industry, but there was a huge gap in knowledge even within our industry.”

With an amount of funding from Meat & Livestock Australia that they won’t specify, Daws and Ludeman launched The Sheep Collective. Members with a stake in the trade were invited to join; the website was soon filled with favourable video testimonials by farmers, buyers and exporters. “It was storytelling, and the response has been far beyond what I’d expect,” says Ludeman. “Text messages, phone calls and farmers coming up to talk to me at agricultural shows. They want a reason to support us.”

The next phase was to run behind-the-scenes tours for sympathetic politicians on sheep ships in Fremantle port — ships filled with Emanuel’s animals but exported under another licence holder’s permit. Then a couple of months ago, the charm offensive ramped up. A dozen media outlets were invited by Ludeman to join The Sheep Collective’s first media tour of a sheep ship, the Al Messilah.

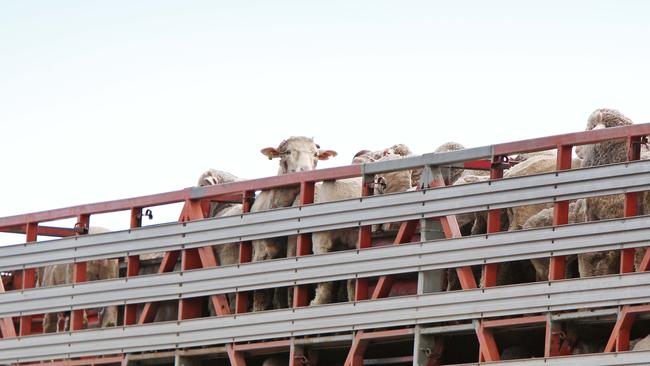

On the day, the optics are carefully managed; cameras and mics are set up near a consignment of healthy-looking sheep being moved off trucks along narrow races. Under the watchful eye of veterinarians, 63,000 animals stream up the gangway until pens on all 11 decks are filled. On board, the media’s attention is drawn to the clean decks, new airflow equipment and the way animals are poking their heads placidly through bars to reach clean water and feed troughs. There is ample space for sheep to stand, thanks to a 17 per cent reduction in stocking rates. It’s one of dozens of recommendations accepted by Littleproud’s department since the “short, sharp” review that followed the Awassi deaths.

There is no mention of the murky history of sheep deaths on the Kuwaiti-flagged Al Messilah, though. A year before the Awassi Express incident, 3000 sheep died en route to the Middle East. Nor is it mentioned that the ship had previously been barred from leaving port by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority until repairs had been made.

The media are not the only invitees on this tour. Standing nearby are Akubra-wearing farmers, stock agents, truck owners and feedlot operators, all part of the chain that delivers 1.7 million sheep annually to ports in Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Their message is clear: animal activists on the eastern seaboard must understand that this industry matters in the west, where one-third of all sheep and lambs leaving farms end up in livestock export ships.

Livestock agent Ty Miller, from the rural WA town of Wickepin, says: “I inspect and market the sheep for my clients. I have a look at them on farm and then get the best markets for them. Often that’s live export.” He explains that the merino sheep being loaded onto the Al Messilah — mainly castrated rams — have been bred for wool, and their meat is a secondary product. As adult sheep, they were never going to find their way onto the dining tables of Australian consumers. “Lamb is what Australian consumers want. You put mutton or hogget out there and nobody will buy it. Whereas other countries prefer older sheep because of the flavour.” Why not slaughter sheep in Australia and export them as chilled carcasses? Miller says live exports are preferred due to air freight costs and religious preference for live sheep in the Middle East.

Livestock truck owner Andy Jacob points down from the ship’s upper deck to his fleet of long-haul vehicles; they transport more than 30,000 sheep and 10,000 cattle from across southwest WA to Fremantle each year. “It’s extremely important — 80 per cent of my business relies on the trade, so without it my business would collapse.” He admits the Awassi Express footage was “disappointing, but it’s not the norm, not the standard we stand by”.

Several Sheep Collective members milling about on the wharf say they doubt the authenticity of the horrific Awassi footage — “but don’t use my name”. They say they felt vindicated when, in January, newspaper headlines claimed a “cash for cruelty” deal had been struck between the whistleblower on board the Awassi Express and pro-animal lobby group Animals Australia. “You saw the emails,” says one man. “The guy was offering to cut off ventilation on the decks to fake bad conditions.” He didn’t accept that the same emails showed Animals Australia discouraging the whistleblower from doing so. The department is still investigating.

Support for The Sheep Collective comes from the highest levels of agribusiness. National Farmers’ Federation president Fiona Simson addresses the media before they clamber on board. “We absolutely accept that we need to have transparency for people to have trust in this industry,” she tells the gathering. “But I can see the sheep being loaded are in good condition, they look well-fed and are being loaded with care with independent vets.”

This scene could change drastically five or six days out at sea, or as ships enter the sweltering heat of a Middle Eastern summer. “That’s exactly right,” Simson responds, not missing a beat. “And that’s why we have independent vets on board — ships like this are taking pains to record video footage and have live feeds when they are on the ocean.”

When the media assembles in Al Messilah’s operations room, Ludeman informs them the tour is about telling “the whole supply chain story, which is what The Sheep Collective is all about”. She presses a button and a video shows sheep arriving in Kuwait after a 14-day voyage. “I was present there in January and February,” she says. “You can see livestock coming off into the feedlot and being inspected again by the veterinarian.”

The vet in question is Dr Majid, a Kuwaiti citizen who, Ludeman says, “we have helped train”. Dr Majid works for Kuwaiti Livestock Transport and Trading, the Kuwaiti government’s part-owned importer that partners with Emanuel Exports. It also owns the ships it uses, the Al Messilah and the Al Shuwaikh. The video shows the interior of a gleaming abattoir in Kuwait City; it opened in January with several WA farmers in attendance. Ludeman says KLTT has spent about $500 million on the abattoir, new feedlots and a $100 million vessel being built in Croatia. “It’s all been facilitated and designed by Australian consultants through Meat & Livestock Australia and LiveCorp and other funding initiatives that have helped the trade continue.”

Again the message is clear: everyone with a stake is determined to keep live exports very much alive. What Ludeman doesn’t spell out is that Emanuel is continuing to send hundreds of thousands of sheep overseas, despite losing its export licence, because of its close relationship with KLTT and KLTT’s Australian subsidiary, Rural Export Trading WA. Graham Daws co-founded RETWA in 1973 and was, for a time, one of its directors.

Emanuel was the exporter, and KLTT/RETWA the importer, for all five livestock export ships to the Middle East between May and November 2017, the voyages during which the damning video footage was taken. When the federal industry regulator cancelled Emanuel’s export licence in August, RETWA applied for a licence. Despite a written objection by Animals Australia, the licence was granted to RETWA in October.

The swapping of licence holders has happened before, says RSPCA policy adviser Jed Goodfellow. “RETWA and Emanuel are closely affiliated trading partners — they’ve shared the same directors and the same live export ships.” He says RETWA had its export licence cancelled in 2004 following 25 voyages resulting in high sheep mortality within a two-year period. “And when this happened, Emanuel Exports filled the gap to provide export services for RETWA. Now that Emanuel’s has had its licence cancelled, RETWA is stepping back in.”

The business links are all confirmed in a diagram that Nick Daws has earlier passed across his desk. It shows that until mid-last year, Emanuel managed all export processes, licences and compliances, while RETWA and KLTT managed the sheep feedlots and livestock vessels. A second graph shows the current situation: Emanuel procures and prepares the livestock, after which RETWA and KLTT swing into action to provide the export licence, feedlot and vessels.

Daws agrees that the relationship between the three companies is “close, but Emanuel Exports has no direct financial interest in KLTT or RETWA”. He insists Emanuel has “been penalised significantly” by losing its licence. “It’s cost us millions.”

The Awassi Express has disappeared from history; renamed Anna Marra, it now ships cattle to Asia. If Emanuel Exports gets its export licence back, it too is likely to change its name. Its link to the Awassi footage will fade, at least in the public’s mind. Perversely, that same disaster may have resulted in prolonging the live sheep trade, the opposite of what animal activists hoped for. The exposure of its ugliest side has forced the trade — and the government agencies that regulate it — into reforming its operations. As if to acknowledge the fact, The Sheep Collective issued a statement last month saying: “The sector has significantly transformed, and will continue to innovate, to provide open transparency across the entire supply chain.”

That simply isn’t true, say Animals Australia and the RSPCA. The worst offenders, their ageing ships and the same scorching destinations are still in play. “As long as live sheep exports continue, it’s a disaster waiting to happen,” says the RSPCA’s Goodfellow.

Exporters have agreed to halt live exports to the Gulf in the height of summer from June to August, but the Australian Veterinary Association believes they should cease over all warmer months between May and October. The federal government has also promised a $2.3 million trial to test whether dehumidifier equipment can reduce heat stress on ships. If it works, exporters might argue that year-round shipments should resume.

As for the success of The Sheep Collective, Daws is pleased but claims he didn’t do it for Emanuel alone. “I did it for the farmers, the truckies, everyone. I did it for the industry as a whole.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout