Li Cunxin’s final act: Ballet legend retirement and health struggles

Ballet supremo Li Cunxin faced down his mortality after he fainted suddenly and was airlifted off Hayman Island last year. What happens when the mind is willing but the body – once limber and powerful – is not?

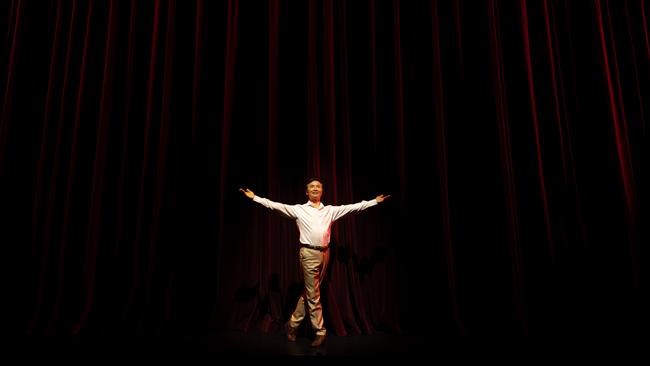

The final time Li Cunxin danced his beloved The Nutcracker, during the 2017 festive season, he was harbouring a secret. His wife Mary knew. But the crowd filling Brisbane’s QPAC Lyric Theatre, eager to see the ballet superstar come out of retirement at 56 for a one-off performance, had no idea he was adjusting his routine as the faintly sinister magician Drosselmeyer around a torn calf muscle.

“We didn’t want him collapsing in the middle of the stage,” says Mary, the former elite ballerina who’s been married to the man known as Mao’s Last Dancer for nearly four decades. “I said, ‘It’s not particularly classical, but can you hop through the turns instead of going up on your toes?’” Yes. Yes, he could. Queensland Ballet’s artistic director soldiered through on a painfully compromised leg and the sold-out audience remained none the wiser. It took three months for the damaged calf to heal.

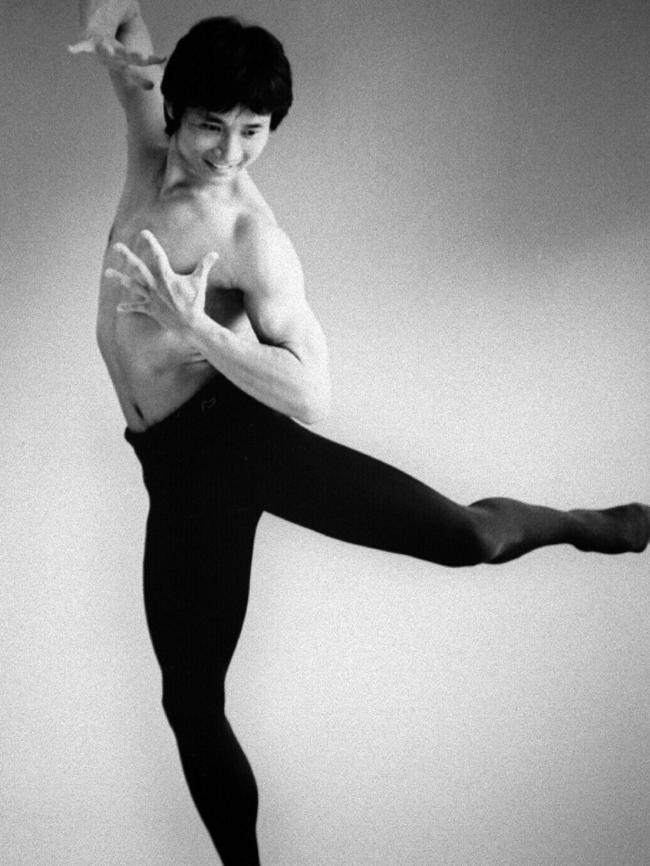

Dancers are used to the physically punishing demands of their art; it’s the price paid for conjuring such beauty and grace with their bodies. Li learned this lesson early. Plucked from a life of grinding poverty at age 11 to attend the Beijing Dance Academy in Chairman Mao’s China, he tore his untutored hamstrings during the audition. Li danced through the pain, later defected during a cultural exchange in Houston, Texas, and went on to become an international star, all of it documented in his best-selling memoir and subsequent film.

In November last year, however, Li encountered opposition he couldn’t push through. The 62-year-old fainted during a rare family holiday and had to be airlifted from Hayman Island to a Townsville hospital. “They discovered over a litre of fluid around my heart, which then triggered atrial fibrillation episodes,” he says. “Mine are very severe; it feels like a heart attack is about to come on. It’s agonising and it can go on for hours.” He’s taking pills and has had a defibrillator installed. “Am I out of the woods now? I don’t think I am.”

Mary, too, has health issues. QB’s ballet mistress and principal répétiteur, 65, was diagnosed with cancer last year and has been undergoing radiation treatment. “It was a total shock, because both my wife and I were so healthy before,” Li says. Also a shock: the June announcement that, at the end of this season, they both will be retiring from the company they’ve steered to greatness. Tributes have come pouring in: Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk says Li is “an inspiration to generations of dancers”; Queensland Ballet chair Brett Clark calls him “a kind of superman”. Filmmaker Baz Luhrmann and his costume designer wife, Catherine Martin, became fans when they moved to Queensland while filming Elvis during the pandemic. “Li’s impact on the creative landscape of Australia will be felt for years to come,” Luhrmann says.

Having just flown in from overseas, Mao’s Last Dancer director Bruce Beresford was taken aback when The Weekend Australian Magazine informed him of Li’s retirement. “I just had lunch with him in Brisbane earlier this year and we reminisced a lot about the film and the fun we had making it,” he said. “I didn’t know he was unwell.” The veteran filmmaker paid tribute to his friend: “He’s not only a wonderful dancer but a skilful communicator, with a keen business brain.”

As Li settles into a chair at QB headquarters in Brisbane’s Thomas Dixon Centre, an historic former shoe factory, he admits to having mixed feelings about retirement. “On one hand, this is my baby,” he says. “This is our love and passion and we are so proud of what we have created collectively, not just Mary and I but the team of dedicated, passionate, talented people. On the other hand, I feel that with both our physical health challenges, we can’t put in the same commitment and energy any more. Our issues are going to require ongoing attention and care.”

The Lis have three children: Sophie (who was born deaf and features in Rockhampton-born Mary’s own memoir, Mary’s Last Dance), Thomas and Bridie. “It will be good to be able to spend some quality time with each other and with our family and our closest friends, who have all been really neglected because the ballet has been all-consuming,” he says.

Li’s office overlooks a shiny new dance studio bearing his name, part of a $100 million refurbishment completed last year. It’s one of a list of accomplishments attached to his legacy: since he took on the role of artistic director in 2012, the number of dancers has doubled, staff has quadrupled and the company’s annual budget has grown from $5 million to $28 million. “Plus we have infrastructure investments worth $144 million,” he says. “I don’t really know of any performing arts company that has experienced this kind of quantum leap of growth in such a short time.”

Did he have that kind of expansion in mind when he took on the job? He laughs. “No, I would have scared everybody away!”

Queensland Ballet executive director Dilshani Weerasinghe remembers Li coming in like a whirlwind, “effervescent with possibility”. “He doesn’t see any boundaries,” she says. “That first year was a white-knuckle ride, because we had been fairly local and then suddenly we were bringing in stages from London and Texas, and the costumes and designers were coming from Birmingham. It became international and lifted the bar on talent that came in.”

Mary had encouraged Li to relinquish the stockbroker’s job he’d taken in Melbourne after finishing up as principal artist with The Australian Ballet, and move the family to her home state. “I just knew he would be amazing, because he’s just a born leader, a visionary,” she says. “His motto is, ‘If you don’t try, how do you know you’re going to fail?’ And I don’t doubt him, because I’ve seen so much magic happen with him in my life.”

Li looks trim and fit in a tailored jacket and jeans, his fabled charisma on high-beam as he talks about the company’s “world-class” stand-alone ballet academy, the new production centre being built, and the “thriving cultural hub” the revamped headquarters has become. It’s hard to imagine him in retirement, though he does speak longingly of the beach at Coolangatta, on the Gold Coast, where the Lis have a weekender. “Initially, there were lots of different offers coming in, but I’m not saying yes to any of them,” he says. “Mary and I definitely want to take some time out; the past 11 years have been absolutely unrelenting.”

His good cheer falters momentarily when talk turns to Queensland Ballet’s final performance of the year on December 20. “I don’t know how I’m going to feel on my last day,” he says. “I think it’s going to be very emotional.” Fittingly, the company is performing a work that has marked many milestones in Li’s storied career: Tchaikovsky’s own swan song ballet, The Nutcracker.

Dom dom dom-ba-dom dom. Li is swinging his arms, marching his feet and laughing at the memory of the stern revolutionary ballets he was made to dance as a youngster. There were only two permitted in Maoist China: The Red Detachment of Women and The White Haired Girl, both commissioned by Madame Mao’s Gang of Four as part of the party-approved Eight Model Works. “They were all about revolution and marching,” he says. “The colours were all red and the props were things like guns, grenades and swords. The costumes were just cut-up holed pants and patchwork, and it’s all danced with the fists, you know?”

Li’s enduring love for The Nutcracker makes sense when you see its Yuletide celebration of pomp and excess as the polar opposite of the severe and unyielding strictures of communism. “When I went to the West, there was this ballet with beautiful walls of flowers and a sugar plum fairy and a magical sugar land full of sweets.” He laughs with delight. “It was just unreal. I might as well just have been chucked onto the Moon, it was so foreign.” Better? “Better,” he says in an emphatic whisper. “More happiness for your soul. You can’t help but love the Tchaikovsky music; it sends beauty and magic through you and naturally makes you want to move in a beautiful, romantic way.”

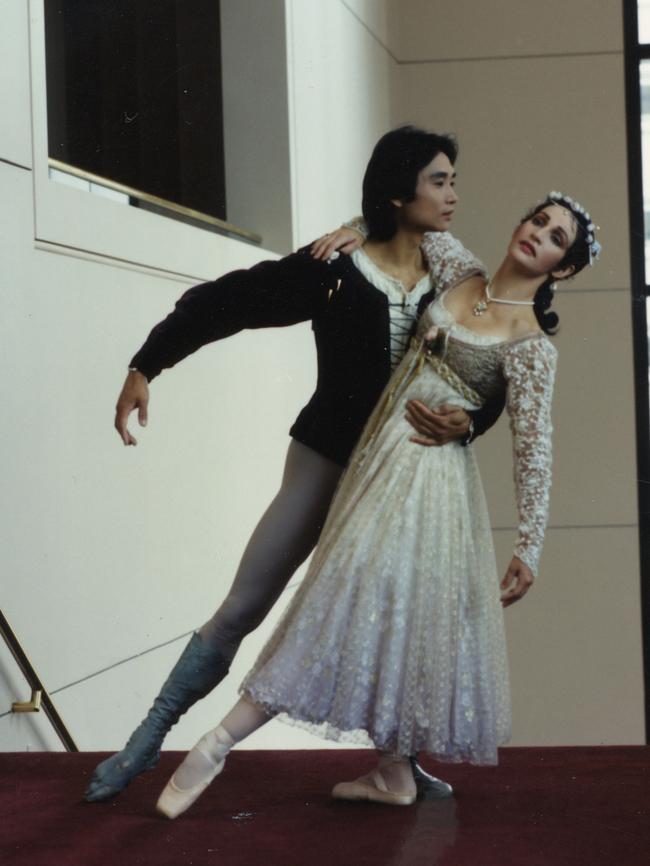

The Nutcracker was the first ballet Li performed outside China, for the Houston Ballet, where he rose to become principal dancer following his defection in 1981. He danced it again in 1991, as the Prince, performing a romantic pas de deux with Mary as the Sugar Plum Fairy. And again, when his parents travelled from China to Houston after Li had endured many years of forced separation from his family. “Probably the most memorable, most emotional moment of my entire career was when my parents came to see me dance The Nutcracker,” he says. “There were a lot of teary eyes in the audience, because a lot of them knew my life story; they had been there in Houston when I defected and was held against my will in the Chinese Consulate. When my parents walked into the theatre, the whole audience burst into applause.”

Li reckons he’s danced just about every Nutcracker role, from an anonymous parent right up to the handsome Prince. “I really felt, as an artist, that I matured through that ballet; it just gives you so many opportunities,” he says. After December 20, Li will fill a different role: that of audience member. He’ll feel emotional, sure, but also full of pride. And always looking to the future. “I’m proud that Queensland Ballet has established this beautiful production as an annual Christmas tradition, a ballet so full of joy and holiday spirit,” he says. “And I hope The Nutcracker will do for our dancers what it did for me, that they’ll be able to grow with the roles. The roles will grow more demanding year after year after year, and be something they can really look forward to.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout