‘Lawless people don’t run our society’: former judge Betty King holds court

She shattered glass ceilings and confronted celebrity crook culture, but in 40 years refused to talk about it. Now ‘Bad’ Betty King is ready to open up.

Betty King had put away a lot of crooks, but the Victorian Supreme Court Justice had never seen a circus like this. It was judgment day for Carl Williams, the baby-faced kingpin of the gangland war, and a seat in the packed courtroom was the hottest ticket in town. The gangland murders had morphed from a tit-for-tat drug war into a ghoulish soap opera where the killers, their wives and survivors had become celebrities, wannabe Sopranos.

The 36-year-old Williams was affecting a look of boredom as he sat behind the Perspex screen waiting for King to hand out the sentence that would determine the rest of his life. Across the courtroom rival crime matriarch Judy Moran was staring daggers at the man who had pleaded guilty to murdering her son Jason and her husband Lewis. Journalists, detectives and gangland types rubbed shoulders. The court heaved with expectation.

In the basement of her home in the inner suburbs, King had spent days writing up her sentencing notes. She detested celebrity crooks. She was already Victoria’s best-known and most-feared judge, a trailblazer who had shattered almost every glass ceiling in the boys’ club of Victorian law over three decades. Yet she was an enigma. Outside the court she drank, smoked, swore and partied hard. She wore blazing colours, leopard print boots and bright cat-eye glasses. She never gave interviews. Yet inside the courtroom King ruled with an iron fist, delivering such withering broadsides to killers and crooks that the public would flock to her courtroom just to hear her words.

“I thought it was absolutely insane what these people were doing,” she recalls of the gangland days. “At one stage Carl Williams said he was more important than the premier because he ran Victoria. And that was reported on the news, on television. I thought you can’t have this. Lawless people don’t run our society.”

On this day in May 2007, the packed court fell silent as King adjusted her distinctive red glasses and began to speak. “You do not get to be judge, jury and executioner,” she said to Williams. “These were not vigilante killings, they were matters of expediency to you… I have a concern that some younger members of the community who are involved in petty crime may be looking to you as some sort of hero. You are not, you are a killer, and a cowardly one who employed others to do the actual killing,” she said during an hour-long dismantling of the drug lord. She sentenced him to life in jail with a 35-year minimum. A furious Williams tried to read a prepared statement but King shut him down. “Remove the prisoner,” she barked. “Ahh get f..ked,” Williams yelled as he was led away. His mother Barbara stood up and screamed at King. “You are a puppet for corruption, you are a puppet of [anti-gangland taskforce] Purana, you don’t deserve your wig and your gown.”

Watching on from the gallery was King’s close friend Jeanine Hickey. After the sentencing she raced to King’s chambers to find her friend sitting alone calmly removing her wig. “It astounded me that she was there on her own. There was no collegiality after something that was so dramatic and of such public interest,” says Hickey.

The two women slipped out a side door and watched from across the road as media scrums formed around rival crime matriarchs Judy Moran and Williams’ wife Roberta. “It was surreal,” says King. “Just walking out in my civvies to watch the madness outside the court with these two camps of women surrounded by the media. I ran into [veteran crime reporter] John Silvester and he looked at me and said, ‘They’ve got no idea you’re here, do they?’ I said, ‘Not a clue’ and just kept walking.”

King and Hickey caught a taxi to an annual charity lunch at a tennis club in South Yarra. “I was late,” recalls King. “And when I walked into the room the MC spoke into the microphone. ‘What did you give him?’ I said, ‘Life’ and the whole place erupted and cheered.” The “lunch” did not finish until 1am. “I just needed to let it all out,” King recalls. “It had been a long road.”

It’s been more like a miraculous journey for Betty King, the girl from the wrong side of town with a public school education who rose to become Victoria’s first female prosecutor, Australia’s first Commonwealth prosecutor, a County Court judge and then a Supreme Court judge who presided over the country’s biggest crime story. Surprisingly, King has never shared her own extraordinary story until now. Throughout her 40-year legal career she doggedly refused to give an interview to the mainstream media. “It’s not about me,” she would say. “I am a judge, not a celebrity.”

Now, aged 71, and seven years after her retirement from the Supreme Court, King has agreed to talk, an agreement that took several long lunches to secure and which was given only reluctantly because she wanted to reinforce the recent campaign against violence towards women. “I do look back on my career with amazement that it was me, this little girl that ended up on the Supreme Court,” she says from the couch at her home. “I don’t know how it happened because I am different from the average judge, I speak very plainly and my background is different to theirs. It was certainly an unusual path at the time.”

In an era when Victorian criminal law was the domain of well-networked, mostly private school- educated white men, King was an oddity. Her father was an accountant but her parents at times ran a milk bar and grocery store in Thornbury, in Melbourne’s north, and then a sandwich shop in the city. The third of four children, she went to a government high school, University High, where she repeated Year 10, a fact that embarrassed her so much that she intended to leave and become a secretary. Her teachers convinced her to finish school and she scraped into law at the University of Melbourne. “I loved the course but I didn’t like university,” she says. “The world of private schools was a world I had never encountered. They all knew each other, they all had shared backgrounds, shared wealth and I probably developed a bit of a chip on my shoulder.”

In any case, she needed to work to survive as a student so was variously a waitress, a typist and a cashier. She lived for a while with her parents above their family’s sandwich shop on King Street in the city, just up from the courts, and she would wander up to the legal precinct to observe the theatrics. “I saw people in their wigs and gowns and I thought, ‘That’s me, I’m going to do that’.”

In 1975, at the age of 24, King became the 24th female barrister to join the Victorian bar in its then 90-year history. When she discusses those early years, King doesn’t complain but she doesn’t mince words. The 12 months she spent as an articled clerk in a law firm after her graduation – then a requirement for all law graduates – was “a living hell” because she was a woman. “I was expected to go and pick up the groceries, wash the car and man the switchboard… on top of my legal work. After I finished the year they said, ‘Would you like to join us?’ I said, ‘I will see you in hell. I am going to the bar, I’m going to be a barrister and I am going to oppose you and I am going to beat you mercilessly.’” She adds with a grin: “And I did”.

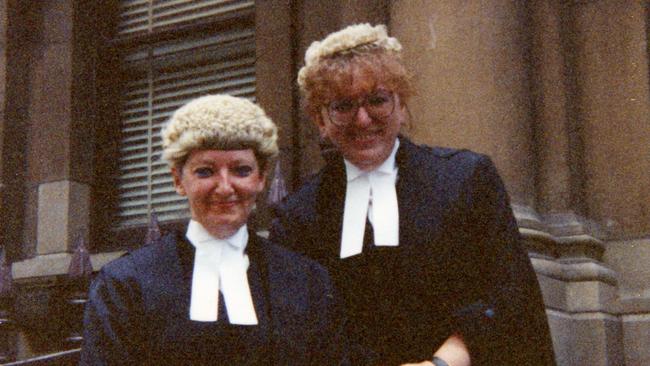

When King joined the bar, she and a colleague, Lillian Lieder, were the only women doing criminal law. King didn’t have contacts or networks and struggled early to get work. “I got my first trial after five months and I was the only female in the room,” she recalls. “That included all the witnesses and police officers, the jury and the judge. The foreman of the jury blew me kisses during my final address. It was all unprecedented in so many ways.”

King stood out in other ways. She loved fashion and ignored the dowdy conservatism of the legal world, turning up to court in bright, bold dresses or suits that rattled old-school judges. Even when she was a judge herself, she would wear her beloved leopard print, including the boots she bought in Harlem. Her distinctive glasses became an Elton John-style trademark.

As a young barrister she once turned up to court wearing a green suit, matching green jacket, green stockings and green shoes. “I thought I looked fabulous, but in hindsight, ugh,” she says. “So I put my gown on and I stand up in the court to announce my presence and the judge says, ‘I can’t hear you.’ So I repeated myself a bit more loudly and he said again, ‘I can’t hear you.’ And I thought, ‘You must be the most deaf old bugger’ so I did it a third time and he just looked at me. So his associate comes over and says, ‘He can’t “hear you” because you are wearing coloured stockings. You need to get some flesh-coloured stockings for his honour or he won’t be able to “hear you” at all.’” So King went to Myer, bought some flesh-coloured stockings and the trial resumed.

Gavin Silbert, Victoria’s chief prosecutor from 2008 to 2018, says King thrived as a barrister because she gave as good as she got. “She is very feisty, and quite outrageous,” he says. “It was very, very hard for her, it was a very misogynistic, male-dominated profession. She mixed it with the best of them and didn’t complain but it would have been pretty bloody tough.”

Elizabeth Gaynor, now a County Court judge, says that when she first joined the Bar in 1985, King and her Lieder were heroes to the new generation of female barristers. “Those two were the real pioneering women in crime, they were the only female icons that we had,” she says. “They had determination, they took people on, head on. They said what they thought and they didn’t wear any bullshit, they didn’t wear any sexism. They were quite intimidating in a professional sense. It was an eye-opener to me and it was admirable.”

King married fellow lawyer James Ruddle and was heavily pregnant with their daughter Elizabeth (now a QC herself) when one day she started getting labour pains in the courtroom. “So I’m pregnant and I’m running an armed robbery trial in the country and we have a jury of 12 farmers. I’m doing my final address and I thought, Oh God… I had to stop and take some breaths. The farmers knew, they were basically breathing with me.” That night she gave birth to Elizabeth and the local paper ran the story under the headline: “Trial end just beat the stork.”

While King is best remembered as a judge, she says her days as a barrister were the most fulfilling. “To me the bar is the most wondrous place, it was like I’d died and gone to heaven. I loved every bit, even the bad bits were OK.” Adds Silbert: “She was a good party animal and she had a lot of fun, but in court, both as a barrister and certainly as a judge, she behaved impeccably.”

King rose quickly to be Victoria’s first female prosecutor in 1986, then the first Commonwealth prosecutor, male or female, including a stint with the National Crime Authority, before a phone call in 2000 changed her life. “She had become a bit of a trailblazer in the law and I was keen to modernise the profession and I wanted to move away from the male, pale and generally stale judicial appointments that seemed to be the norm,” recalls Rob Hulls, then Victoria’s attorney-general. Hulls asked King to become a County Court judge, a role King reluctantly accepted, initially regretted but then came to love. “I missed being a barrister,” she says. “As a judge you have to shut up and it doesn’t suit me. You don’t get to run the case, that’s done by counsel, and you are watching it thinking, ‘Oh no, don’t do that,’ or ‘Oops – too late’.”

Even now, after a 40-year legal career, King detests pomposity and pretence. Outside the court she was always “Betty” rather than “Your Honour” and she is caustic about judges who adopt a haughty attitude. “She hates people who are smartarses or snobs and who think they know everything,” says good friend Hickey, who King met playing tennis more than 30 years ago. “She is very down-to-earth. She is great company, enjoys people and a glass of bubbles and is always the life of the party.” King admits she likes a drink and, until she was 60, a smoke. “I smoked for Australia,” she laughs. “I was always naughty or bad Betty.”

Over a long liquid lunch, wearing cocktail glass-shaped earrings, King takes me on an irreverent and spellbinding journey through almost half a century of Victorian crime – the crooks, the judges, the barristers, the war stories, the outrages, the triumphs and the failures. She is strong-willed, sharp-tongued and often hilarious, but she can also be bitchy, deadly earnest and then hugely generous to those she likes. You can see how she could be both feared and loved, especially when she had the gavel in her hand.

Hulls learnt of King’s growing reputation in the County Court and in 2005 he asked her to join the Supreme Court. “Rob Hulls rang me in New York, where I was holidaying, and sang New York, New York to me to thank me for taking the job,” she laughs. “I didn’t realise at the time but they needed a particular judge to do the ganglands. On my first sitting day the Chief Justice said, ‘Betty, we would like you to take on the Carl Williams matter.’ I thought, well, this is going to be interesting, it was all over the newspapers and it was insane what was going on with the publicity. I thought, how on earth are we going to get a jury that was impartial?”

At that stage the gangland war was easily the biggest story in Victoria, swallowing up pages of newsprint. The death toll was ticking up towards 30. Williams, who headed the gang opposed to the so-called Carlton Crew, was already in custody for a series of murders. “At that stage he was giving interviews from prison,” recalls King. “His wife Roberta was holding interviews almost daily and I thought, ‘This has just got to stop’. I thought, [these gangsters] are treating it like theatre. It was as if they were all acting the part. The Carlton Crew, like wannabe gangsters straight out of television. ‘Hey man, look at me, I’m playing the part of an Italian mafioso’, or ‘I’m playing the part of a hitman’, like Benji [Veniamin]. It was all very odd. I couldn’t believe the media gave them as much attention as they did. So the first thing I did was make a suppression order that was so broad I included almost everything except the family dog. It was against Carl Williams, his wife, the child, the parents. It was too wide and the Court of Appeal altered it, but it worked. Neither Carl, his wife or father could talk or say anything.”

King’s 2005 decision dealt a major blow to the media’s coverage of the gangland war, which had been a ratings and circulation blockbuster. It also meant the media could not report the key fact that Williams was being tried at that time for the 2003 murder of rival drug dealer Michael Marshall.

Then, in March 2007, King received word that Williams was finally willing to plead guilty to three murders and a conspiracy to murder as part of a plea deal. “I thought that would be good as the cost to the community of running these trials was horrendous,” she says. “For example, we had to close all the courts on one side of the Supreme Court every time he moved from the cells to the court and back, because of fear of payback. There were police snipers around the courts for protection.”

The plea meant King could now lift the suppression order, a move she knew would trigger a media frenzy. “There was an avalanche of Carl. There was almost nothing else in the newspapers. Now they could talk about his old trial and the fact he was already convicted.”

The sweeping nature of her suppression order and her blistering remarks during the sentencing of Williams placed King squarely in the spotlight, but the most dramatic moment was yet to come. In February 2008, about six weeks before the trial of hitman Evangelos Goussis for the 2004 murder of Lewis Moran, King was asked to consider whether a new TV series on the gangland war, Underbelly, could affect the Goussis trial. “So I watched all 13 episodes [in one night] and by episode five I was pretty sure I had to ban it. I turned to [my colleague] and I said, ‘I didn’t know that happened’ and he said, ‘Neither did I’ and I said, ‘We’re done, it has to be banned’. If I was treating it like reality, how would a jury see it?’”

King knew that banning the TV series in Victoria was a big call. She wasn’t even sure if she had the power to do it. “It had never been done before as far as I could tell, and I thought to myself, ‘I’m a Supreme Court judge, I have a lot of inherent jurisdiction, so here goes’. Her decision was examined all the way to the High Court and stood up to the scrutiny. “There was lots of criticism of [the ban] of both the Williams’ trials and the series Underbelly,” she says. “But I didn’t care much because a fair trial was the most important thing to me. The ratings of Channel Nine were not my concern.”

Media lawyer Justin Quill, who battled with King on behalf of media outlets over suppression orders more than a dozen times in the Williams case, says each appearance before her was “difficult, lively and entertaining”. “Her Honour was particularly strong in her opinions,” Quill says. “She would listen, but you knew you would have to produce some good arguments to sway her. And technical legal arguments would never work – her Honour was very practical in the way she approached things.” Quill concedes the unique nature of the overlapping cases in the gangland war made suppression orders more necessary than usual but he still believes King “did not place enough trust in juries. No doubt her Honour would disagree with me – and feel comfortable making that disagreement clear to me.”

King was actually a big fan of the first Underbelly series. “I loved the show [but] it made their lives seem far more glamorous than they were,” she says. “The sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, that’s what they wished they had. But they [the real gangsters] weren’t as attractive, they weren’t sexy and they didn’t get the gorgeous girls. The girls I saw weren’t particularly pretty, a lot of them were what you might call very ordinary.”

Despite the high profile of the gangland trials, King’s daughter Elizabeth says she didn’t think her mother was overly stressed by being in the public spotlight. “Obviously [these were] complicated cases with a big workload but she wasn’t really that fussed with the press attention. She just wanted to do a good job of managing the trials and making sure they were fair.”

While King is best known publicly for her role in the gangland trials, in legal circles she has another claim to fame. She was the first judge in the country to impose tough sentences for domestic violence offenders at a time when maiming or killing a partner was widely viewed as a lesser crime than regular murder. A 2017 study by the UNSW Law Journal concluded King was a “feminist” pathbreaker in Australian law for her sentencing on domestic violence, for “rejecting victim-blaming accounts and other efforts to minimise defendant’s culpability and instead naming men’s anger, rage and violence for what they were and insisting defendants took responsibility for their behaviour”.

Says King: “I believed from the time I started doing crime that violent crimes against women were under-sentenced. It was always, ‘Look what you made me do to you’. I thought, ‘This is your home, this is your safe place, yet he’s allowed to come in and go, ‘You didn’t cook my dinner properly’, or ‘You said I’ve got a small dick so you deserve to die’, or ‘You were wearing tight clothes [so] you made me rape you, it’s your fault.’ It is victim-blaming and I always thought [those excuses] were an aggravating factor rather than a mitigating factor. You know: ‘She pushed his buttons.’ So what?”

King is full of praise for the courage of Grace Tame and Brittany Higgins for speaking out about sexual violence. “It is finally taking us away from the ‘look what you made me do’ and I applaud every single move they make,” she says. “They have shown that women are not prepared to put up with the lack of action in holding men accountable for their treatment of women in the home or the workplace. About bloody time.”

When asked more broadly about her views on rehabilitation of criminals, King says she would like to see more alternatives to prison, especially for young offenders. “Imprisonment won’t rehabilitate anyone,” she says. “I have a strong belief that if you can keep a male out of prison until they are 30 there is a real chance they will avoid it forever. I would prefer to see the money we spend on imprisoning people being spent on providing housing, education and a liveable income.”

But some people, she says, can’t be rehabilitated. “I don’t think Carl Williams would have reformed,” she says of the crime boss who was killed in prison in 2010. “He was brought up in that criminal milieu and enjoyed mixing with other criminals. I think it probably made him think his life was exciting where in fact it was all rather sad and pathetic.”

In 2015, after 40 years in criminal law, including five years as a judge in the County Court and 10 years in the Supreme Court, King decided she had clocked up enough murder trials. “About seven months before my 65th birthday I was given a trial involving the murder of a 13-year-old autistic boy,” she recalls. “He’s been killed with an axe, he was helping defend his stepfather and they just chopped his head open and bits of his fingers flew everywhere. I was reading these details and I just closed [the brief] and said, ‘I’m done, I don’t want to do this anymore. I don’t have any murders left in me’.”

So King retired at age 65 rather than the statutory retirement age of 70. At her farewell she said simply: “I no longer wish to view the relentless parade of dead bodies and destroyed lives.” But she didn’t retire completely. From 2018 to 2021 she was the inaugural chair of Victoria’s independent Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board, which was set up to ensure the smooth implementation of the state’s voluntary assisted dying laws, which she supports passionately.

Looking back, King says she never thought much about those “glass ceiling” moments or whether she might be paving the way for future generations of women in criminal law. “I think about them much more now, but at the time you just sort of took what happened and dealt with it,” she says. “I never put myself in the category of being brilliant, but I was a hard-working judge. I worked hard and played hard. I got on with things. I was a workhorse.”

She doesn’t miss the law or crime and tries to focus on the good memories now rather than the bloodstained ones. “I don’t watch anything with violence in it anymore. I don’t read about violence, I don’t watch it, I’m done with violence.” She pauses, then corrects herself. “Actually, I love an Agatha Christie murder mystery where it’s all about clues,” she says with a grin. “But no body parts, please.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout