Late risers: school dropouts who made it anyway

They may have failed their final year or dropped out of school. But these high achievers found another way.

School rules. So says almost every public and private employer and mostly, so say all of us. There are infinite pathways through life but one of the few universally recognised requirements for almost any form of success is education, a human right so valuable, according to a 2017 UNESCO report, that the global poverty rate could be more than halved if all adults completed secondary school.

Not everyone, however, will succeed in their final exams, soon to begin around the nation. By age 19, about a quarter of Australians will not have completed Year 12. Then what? There are many ways to live a life and failing to complete high school is not necessarily the end of opportunity.

Federal Minister for Defence Industry Melissa Price, a lawyer at 31, left school at 15. So did Helen Lynch, the country’s first female bank manager and later a director of Westpac, as did her friend Susan Kiefel. After Year 10, Kiefel started working in a typing pool at a building society and then as a receptionist at a barristers’ chambers. In 2017, at 63, she was appointed Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia.

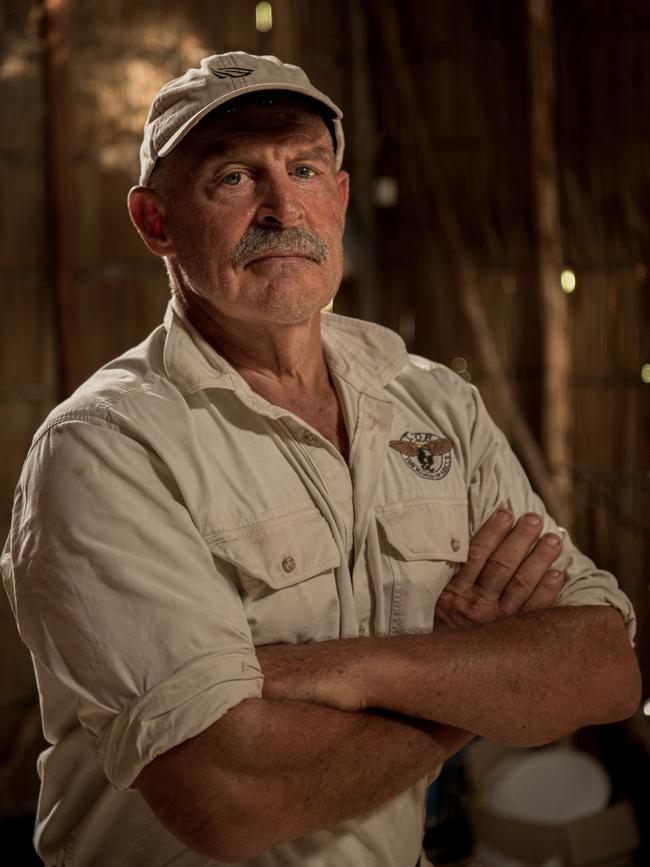

Shane Drumgold

Left school in Year 9. Now ACT Director of Public Prosecutions

It was unwise to mess with Shane Drumgold as an adolescent. “At school I think it would be fair to classify me as the kid who most people tried to stay away from,” Drumgold, 55, says of the confrontational tendencies of his youth and his assumption that fighting was the best way to assert himself. “There was a culture that when you start at a school you would get this pecking order and someone fights.”

Drumgold grew up in Sydney’s outer west in the then new suburb of Mt Druitt. He attended local primary and high schools “without putting in an assessable piece of work” and even early on, it seems, he was a marked young man. “I distinctly remember being in the disadvantaged class,” he says now, eloquent and considered. “That was the class where it was expected nobody in the class did anything assessable.”

Although he was never overly enthusiastic about school, “I remember enjoying not being at home. I remember enjoying the respite from there”. His father, an alcoholic, was chronically mentally ill for most of his life, and Drumgold and his two older siblings grew up in a chaotic household amid violence and drugs. The family lived on their father’s disability pension, which he sometimes supplemented by pumping petrol. Occasionally their mother worked in a factory clearing up scraps of fabric.

Drumgold was 12 when his twin brothers were born. A year later the family moved to NSW’s mid-north and he was enrolled at the local high school. “I didn’t know how to interact with people. I don’t think I had any really close friends at Taree High School because I was this unusual, disruptive kid. I walked into this country town and into this school and thought, who do I fight? And I remember people saying, ‘That’s not the way we operate here.’” His transition out of school began not long after. “Some work came up,” he says. “There was no day when I left school. It wasn’t that ordered. It was more that I would turn up when I didn’t have something on. And then I had something on more than showing up. I think I just stopped showing up.” He had not yet completed Year 9 and his home life had become so unruly he doubts either of his parents were even aware he had left school, although it would have mattered little anyway. No relative or teacher had ever encouraged him to stay.

“I don’t know of anybody in my family anywhere that had been to university or had even finished Year 10 or 12. That’s part of your mindset: that’s what other people do, it’s not what I do, it’s not what our family does.”

The one thing he retained from his curtailed schooling was a love of reading and he delved into Socrates, which touched on his love of reasoning. “I found logic a sport,” he says. “I was a pain in the arse where I would take a proposition from somebody and try and pull apart the logic with it.” He re-enrolled at high school several times but never lasted long. “I always felt that people judged who I was and where I was from.”

After one of his twin brothers died of encephalitis, the family moved again but even in Newcastle, where he again tried to return to school, his social issues persisted. “I felt ostracised. I don’t think I was, but in my head I had this thing where I felt very judged.” And then he became a father. He had met a girl before leaving school the first time. They married and in 1984, when Drumgold was 18, their son arrived. “When Chris was born I just felt this overwhelming desire to have some direction and to start to build. Prior to that I was just drifting and I just had me. Now I was responsible for someone. I remember looking at him and it was just magic. And I found this motivation to go and do something.”

Through a series of odd jobs – labouring, delivering spare parts, collecting insurance premiums door-to-door – he stumbled on the appeal of a directed, more solid life. Within a few months he experienced another momentous event. “Probably one of the happiest days of my life is when I got an interview with Australia Post and they said, ‘You start at Penrith post office on Monday as a telegram boy.’” Handed his new uniform, he changed into it in a city toilet block and rode the train back home with a newfound sense of belonging. “And I remember thinking: this is the start of the rest of my life. And frankly, it was.”

In 1993, aged 28, having been rejected repeatedly because he had not completed Year 10, he began studying for a management certificate and eventually an economics degree. In 2001 he completed a law degree, and later a masters in international law.

In December 2018, 40 years after he left school for the first time, Drumgold was appointed Director of Public Prosecutions for the ACT. Ultimately, he says, it made no difference that he did not finish school with his cohort. “Not in the slightest. That’s a really important message. You think your feet are set in concrete at 17 or 18,” he says. “It takes two things to do well. It takes a bit of ability. But it also takes a whole lot of grit.”

Bronwyn Carlson

Left school at 15. Now professor of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University

No one had any great expectations for Bronwyn Carlson. Not her mother or her estranged father, and apparently not even her final high school headmaster, who suggested she consider a future as a cleaner.

“I got told once I was really good at drawing. That’s the only praise I remember at school,” Carlson, 56, recalls from her Sydney office, less than 100km from where she started on a fractured schooling path that would span multiple states and countries and more than a dozen institutions. “There was no future for us at school; my younger sister was told she could do cooking,” she says. “Nobody cared that you didn’t go [to school]. Your family didn’t care that you didn’t go, because they just left and went to work in factories.”

The second eldest of four children, Carlson was born into chaos in 1964. “My father was an alcoholic and we moved from town to town growing up around Australia where he would look for work.” From Wollongong to Geelong and Oodnadatta, poverty and disruption became the pillars of her childhood. “We identified as not white [her mum is indigenous] so there was all that exclusion at school, plus we were poor. And then when you’re put in and out of school at different times in your life… it causes all sorts of troubles.”

By the time Carlson was seven her father decided to take the family to New Zealand, “supposedly for a better life”. Between drunken parties and living in a house slated for demolition, the disorder continued. A few years later her father left and returned to Australia. Carlson’s education continued in a limited and haphazard way until she was 14. “Even though I have always been an avid reader and pretty cluey as to how the world works, you get left behind if you don’t follow a certain path.” Eventually, her interest in learning waned; she attended school less frequently. “Me and my younger sister got into some strife. We were considered uncontrollable by the court and put into a children’s home. And from there it was decided by the court that our mum had no control over us. So we were deported.”

In her mid-teens she was sent back to Australia to live with her estranged father and his new partner in Katherine, a precarious arrangement that soon saw her leave the NT, and school, move back to Wollongong to be with her maternal grandmother, and eventually back to New Zealand. At 15 she started work at a factory making doonas and later clothing. “I could whip up 400 collars and cuffs for shirts every day.” Eventually she married, found stability, had four children. After decades away, she returned to Australia with them and in 1998, researching her maternal family history, headed to the Aboriginal Education Centre at the University of Wollongong to examine some documents. At 35 she was stepping into a university for the first time.

Was she daunted? “It literally didn’t mean anything. I had no concept of it because I had never known anybody in my life who had been to university. Everyone worked in manual jobs,” she says. “I just got on with earning some money and trying to stay alive.”

From her own halted schooling Carlson had retained a love of reading, a pursuit that had been encouraged by her maternal grandmother, who would pull out a dictionary whenever she visited. “She said, ‘You never know when you need those flash words Bron.’” And she had retained her natural inquisitiveness. “I wanted to know why some people were poor. How come the world works like that?” Still, when a student support office asked if she had considered enrolling in university, Carlson was initially amused. The closest thing she knew to aspiration was her older sister, who had finished school and worked in a bank. “She was rocking it.”

Within months, Carlson was accepted to study sociology and Aboriginal studies. Using the $270 her late paternal grandmother had left her, she bought her first sociology books. She finished her PhD in 2011 and three years ago she was appointed professor of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University.

“If I’d believed that I would amount to nothing then I would amount to nothing,” Carlson says. “You will always be what you imagine yourself to be. So if you imagine yourself to be a doctor, you will be a doctor. Why the hell not?”

Barry Kirby

Failed Year 12 exams. Now remote rural GP with obstetric skills saving women in PNG

As a young scholar, Barry Kirby was an outstanding sportsman. From leadership to athletics, he excelled at most things. In his final year at Brisbane’s St Laurence’s College he was vice-captain and held the school record for shot put. Then he sat his Year 12 exams.

“I think my parents were a bit disappointed with me when I failed high school. I didn’t pass anything, even English,” says Kirby, 70. “Can you imagine the vice-captain of the college, head cadet, captain of the athletic team, and I failed high school? I think everyone was disappointed.”

Except Kirby. “I knew it was going to happen. I’d paid attention but I just couldn’t grasp anything. My focus was to go on the land. I was going to be a farmer.” While his parents – his mother was a nurse and his father, a trained carpenter and a farmer – sought a good education for him, their son saw himself living on the land, without focusing on the steps it would take to get there. “I was interested in classes and I would do my study at home but it just wouldn’t stick. It didn’t have any significance for me. I loved the outdoors and sport and I just thought I would put study off.”

By the time his dismal results came in, cattle prices were low and his parents could not afford for him to repeat his final year, so he began the first in an eclectic line of jobs. He shovelled coal into hessian bags. He became a boilermaker’s labourer at a steel mill. In Sydney he filled out invoices for BP, completing a month’s work in a fortnight and spending the remaining weeks idling at his desk, drawing pictures of the countryside, until 12 months later “all of a sudden there was this bolt of lightning that said, ‘what the hell are you doing here?’”

At 20 he became a carpenter like his father and found joy working with his hands, a job that took him to rural PNG to build a school and student boarding house. But while his days were occupied, his mind would increasingly turn to the low standard of local medical care and in particular the plight of expectant women who faced an alarming maternal mortality rate. After two or three years there he “started to think maybe I could be doing medicine” but would push aside those ideas. “The person who had failed high school was never an academic. It’s a crazy stupid thought.”

Then, one night in 1990, he found a woman on the road near his village. She had chronic diarrhoea, probably HIV-AIDS, and she had been cast out as a witch. Kirby drove her to a health centre but no doctor was there so he put her to bed and found someone who promised to watch her. When he went back in the morning, she was dead. At 40, Kirby decided he would become a doctor.

“The thought had been nagging me for a long while,” he says. “The lady dying did it. I walked out of that hospital saying I am going to give this 10 years, if it doesn’t work out I will go back to carpentry.” He enrolled first to study biomedical science. “I didn’t now how to apply to uni so I got my sister to help me. I needed a CV but I didn’t know what a CV was so I hired a guy in Sydney to write why I wanted to do medicine in two pages… And lo and behold I was accepted.”

He finished his degree with honours at Queensland’s Griffith University and then, repeatedly rejected from medical courses because of his age, he completed a PhD. In 1997 he was accepted to study medicine at the University of PNG, the country’s only medical school. He graduated at the end of 2000 aged 50 – just within the decade he had allowed himself to achieve his goal.

Twenty years on, Kirby runs a rural obstetrics practice in remote PNG conducting maternal health checks, training midwives and encouraging mothers to have their babies delivered at health centres. The vice-captain who failed high school was last year named Griffith University’s outstanding alumnus.

“It’s important to do as well as you can,” says the late learner, “not only for the sake of yourself and all the hard work you put in, but also recognise all the sacrifices your parents have made for you. But don’t be disappointed if your expectations aren’t met. Because you’ll find in life that that’s meant to be. And what you are going to be in life is yet to be revealed.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout