King Charles III coronation banquet: inside the history of the royal feast

Charles III’s coronation banquet is unlikely to resemble the extravagant spectacle and culinary fashion of his forebears at court.

“Cut the heads off neatly,” said a palace staffer when preparing for the king and queen’s coronation in 1937. Normally such comments would elicit gasps of “heresy!”, swooning at the thought of regicide; and shouts of “arrest that man!”. But have no fear. This was not an attempted messy revolution with a sharp-looking Madame La Guillotine joyfully waiting in the courtyard. Instead, it was the harmless royal chef giving precise instructions on how to recreate the roast quails – or, to be more precise, the Cailles rôties sur Canapés à la Royale – that were a highlight of the coronation banquet for Charles III’s grandparents, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

All the fiddly bones would be removed from the tiny birds before they were stuffed with pâté de foie-gras; roasted; cooled; dipped in a sherry and venison sauce; sealed in a thin layer of game jelly; and presented on a bed of crushed pineapple ice looking lifelike, their “neatly” cut heads reattached on hidden toothpicks. They even had eyes made from a “minute round of truffle in the centre of a little circle of white of egg”, recalled the royal chef, who cautioned that the dish should not be “attempted by any but fully qualified and experienced cooks”.

In the 86 years that have elapsed since, culinary fashions have changed substantially. It’s hard to imagine any heads will be reattached to any animals at next month’s coronation festivities for the former Prince of Wales. Although we don’t know much about plans for a post-coronation feast on May 6 we do know for a fact that nothing will be stuffed with foie-gras. His Majesty has decreed there is no place at the royal table during his reign for these delectably rich and smooth livers extracted from bloated force-fed geese. “Torture in a tin,” he has royally decreed. We can also assume King Charles will dodge the clear turtle soup (Tortue Claire Sandringham) served at the coronation of his beloved mother, the late Elizabeth II. And we can be certain His Majesty won’t be revisiting the coronation menus of his medieval forebears.

For more than 600 years, from Richard the Lionheart to George IV in 1821, the coronation banquet was a sight to behold at the Palace of Westminster. With much pomp the now anointed and be crowned monarch proceeded from the abbey to the hall and took their seat at a marble table beneath a richly embroidered canopy, flanked by an assortment of impressively uniformed royal hangers-on. Dining tables for the most noble of guests – laden with every jewel-encrusted gold, silver or pewter contraption imaginable – stretched the length of the hall. Behind the tables were towering makeshift stands to allow the slightly less noble guests to ogle from on high at the gastronomic oddities about to be served. A scene of colossal ostentation was about to play out. Knights and lords of every title, including a Chief Cupbearer, ceremonially brought forth the dishes. The first was ushered to the King’s table by a procession that included the Earl Marshall, Lord High Steward and the High Constable, each on horseback.

For Henry V’s coronation there were 31 roast swans, along with a smattering of roast porpoises, peacocks and antelopes. Most of the birds were served in full plumage with the raw feathers poked back into the roasted carcasses, enough to make any modern-day health-inspector cringe. Heads were reattached too. For Henry VI there were whole stuffed boar’s heads “enarmed in a castell royall” and a “red leche with a whyght lyon crowned therinne” which, roughly translated from medieval-speak, was a form of red milk with a white lion crowned therein. The mind boggles.

At first glance, the three-course coronation banquet for James II seemed restrained enough, until it was realised the first course alone consisted of 32 dishes as part of a banquet that included “neats udders roasted”.

For centuries a mainstay of every coronation was a truly vomit-inducing dish served at the end of the first course. Known as maupygernon, this frightful concoction was created by the cook to William the Conqueror in 1068, and is thought to have been a fatty and highly spiced greyish-white gruel made from almond milk, par-boiled chicken, lard, sugar, dill, cloves and the “brawn from capons” – that’s the meat from the heads of castrated young roosters.

The “mess of maupygernon”, as it was officially recorded, made its swansong at the coronation of Charles II, who is said to have “graciously accepted the dish but, after examining it, decided not to partake thereof”.

By tradition, as the King started to slurp on this mess, it signalled the start of a commotion at the gates of Westminster. The fanfare of trumpets followed by threatening shouting, echoed across the banqueting tables: the King’s Champion had arrived with an ultimatum for the gathered masses. He recited a high-stakes dare akin to the wedding pledge: speak now or forever hold your peace.

If any person “of what degree soever, high or low” doubted the monarch was the rightful claimant, then it was the duty of the King’s Champion to denounce them as a traitor and a liar – “saith that he lieth” – and challenge them to a life and death combat. In an attempt to provoke and flush out any brave doubting thomases, the defender of the crown then spectacularly threw down his gauntlet with an almighty clang. Suddenly everyone stopped eating.

With the entire hall in a hush, the doors opened and the King’s Champion rode horseback through the rows of tables to the middle of the hall. Preceded by two trumpeters and decked in full armour – with red, white and blue feathers sprouting from his knight’s helmet – the King’s defender repeated the challenge. Then, at the steps of the platform that led to the King’s table, the challenge was delivered a third and final time.

Without so much as a peep of defiance from the room, the King’s Cupbearer swung into action and brought forward a lidded gold bowl filled with wine. The monarch could now breathe easy and drink a toast to his champion. It was now time for the second course.

The spectacular coronation banquets at Westminster last played out in 1821 when George IV seemed more interested in things other than food. “He was continually nodding and winking at Lady Conyngham”, his not-so-secret mistress, “and sighing and making eyes at her”, recounted a cabinet minister’s wife from her vantage in the stands.

By the time of Queen Victoria’s coronation, the banquet had morphed into nothing more than a large private dinner party at Buckingham Palace. It was so underwhelming that the 19-year-old queen devoted a mere four words to it in her diary: “At eight we dined.”

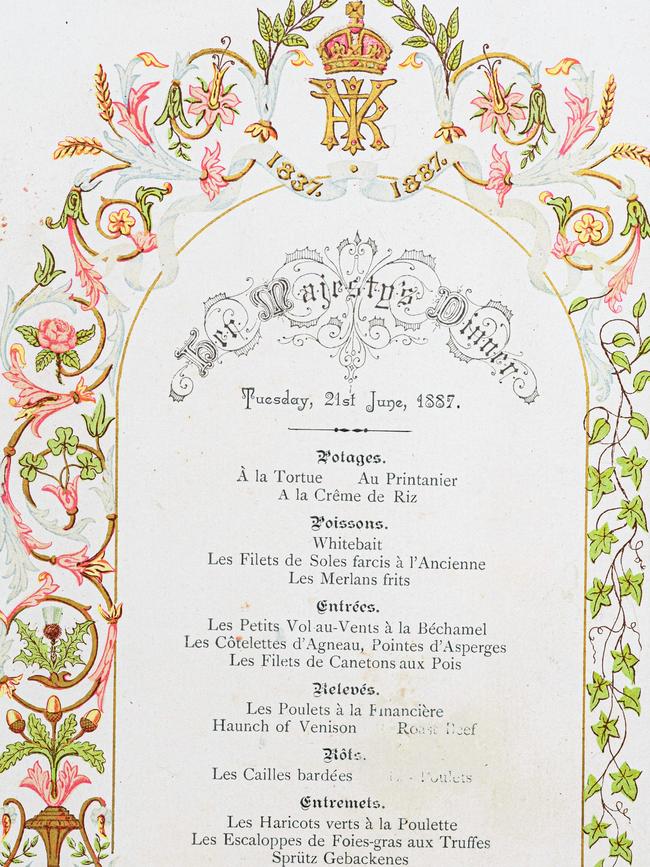

In the decades ahead, however, perhaps making up for lost opportunity, Victoria presided over some stunning banquets to mark her various coronation jubilees. With the kings of Belgium, Denmark, Greece and Saxony in attendance, along with a hotchpotch of various soon-to-rule crown princes and a future kaiser, her 1887 golden jubilee dinner offered guests 15 courses, in addition to a side-table of cold roasts and pressed ox tongue. She loved truffles. Alongside an entire spit-roasted haunch of venison was a delectable serving of Poulets à la Financière. Here the royal chefs had deglazed sautéed suprêmes of chicken in madeira wine before garnishing them with quenelles, cockscombs from the heads of roosters and slivers of truffle; all dressed in a sauce made from more madeira, mushrooms and yet more truffles.

But as the British were scaling back their coronation feasts and the French were moving with speed to get rid of coronations altogether, the tsars of Russia were setting new global standards for imperial splendour. In the mid 1700s, with a wink and nudge to a band of her ambitious loyalists, Catherine the Great quite naughtily had her emperor husband knocked off so that she could reign alone. In her rush for legitimacy, Catherine wanted new symbols of authority and arguably became the Empress of Bling when she placed upon her head a spanking new crown comprising a gobsmacking 4936 diamonds. The usurping empress wore “this heavy thing”, as she called it, to her mid-afternoon coronation banquet at the Kremlin. Matching the glitter of her crown and ermine-trimmed golden robe, the grandly spread banquet tables sparkled with the hoofs of venison and the scrolled horns of the spit-roasted rams magnificently dipped in pure gold.

Just 20 years earlier, Catherine’s mother-in-law predecessor, Empress Elizabeth, had offered her coronation guests a menu of poached bear paws; moose lips in herbed sour-cream; and a stew of sautéed nightingale tongues.

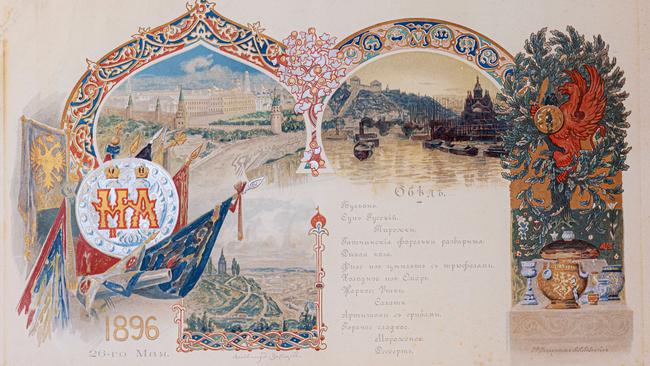

By the late 1800s, as the curtain was preparing to fall on three centuries of Romanov rule, the last tsars had turned their coronations into a week’s worth of glutinous banqueting that included saddles of wild goat, lobsters in aspic, roast hazel-grouse with truffles, jellied partridges and pheasants, giant stuffed sturgeons, and mountains of a Russian favourite, Zalivnoe: elaborate moulds of jellied meats.

At the grandest of these feasts, each dish was presented with magnificent ceremony. “I certainly shall never see again a soup tureen guarded by soldiers with drawn swords”, recalled the French ambassador’s wife of the coronation of Tsar Alexander III. And then a voice boomed, “His Majesty deigns to drink!” To the herald of trumpets, the Tsar raised his gold goblet and took an imperial swig to signal his readiness for the roasts.

Of course, not every dish had to be so decadent. Bowls of Gureyev porridge, a staple of the Russian imperial court, concluded the feast: a humble and delicious dessert made from the skins of baked cream blended into a porridge with honey, vanilla, semolina and poppyseeds then layered with blackcurrant jam, caramelised nuts and topped with a burnt-sugar crust.

In Britain, too, when our new king was just four years old, the famously simple Coronation Chicken entered the royal lexicon when it was served to guests attending the crowning of his mother. Appearing on the menu as Poulet Reine Elizabeth, the recipe was the winning entry when the common-sounding Ministry of Works went in search of a coronation dish that could easily and affordably be replicated in hard-up postwar households and street parties. It’s not certain, however, whether the Queen devoured as much as a morsel of the cold dish of shredded chicken in curried mayonnaise with apricots, given the royal family dined alone at Buckingham Palace following the exhausting ceremony.

The following day our future king featured on the official banquet menu when his mother served “Délices de Soles Prince Charles” (crumbed bite-sized filets of sole with a shellfish mousse) paired with an 1890 Sherry Solera Tarifa, in honour of her son and heir.

Charles’ reputation as a foodie has been cemented over the decades. He was mocked for being an organic farmer long before it was fashionable; he was a founder of the Mutton Renaissance Campaign, an effort to bring back to life classic British cooking; and he ditched the French language on his princely menus so he could better showcase the best of British produce and creativity. His menus, which sound much more digestible than some of the royal servings of a bygone era, include “smoked salmon and scrambled-egg timbale”; “baked halibut with lemon and dill mayonnaise”; “roast fillet of red poll beef with Yorkshire pudding and roast potatoes”; “cold pea and mint soup with an oeuf mollet” (soft-boiled egg; OK, so a sprinkling of French remains), and the delightfully simple dessert to finish – “strawberries and clotted cream”.

If not the food, there is perhaps one tactic from previous coronations that could provide inspiration for our new king. At the crowning banquet of George IV in 1821, the king’s guests included a pack of professional boxing champions. They were there to stop the queen and her supporters from gatecrashing the feast, as the king had banned her attendance following a spectacular royal spat. A tactic worth pondering, perhaps, if Harry and Meghan continue with their carry-on.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout