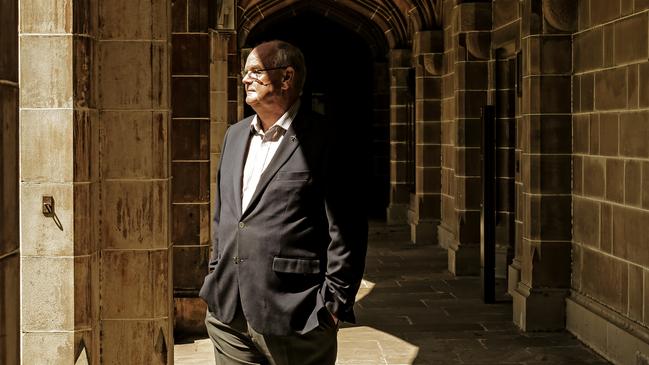

Keith Houghton on the devastating cost of keeping his dyslexia secret

Keith Houghton rose to the top of academia to become the dean of business and economics at ANU. For 40 years he battled dyslexia in complete secret - this is what he’d do differently.

As far as careers in Australian academia go, Keith Houghton’s (BCom Melb MSc (Econ) Lond PhD UWA FCA FCPA) has been what you might describe as sparkling – capped with an eight-year stint as dean of business and economics at the Australian National University, during which time he was also Chair of the University Academic Board. When he retired in 2012 after four decades of university service, he was granted emeritus professor status, cementing this career of distinction.

But during a crucial step while ascending the academic ladder – after he was appointed to the prestigious post of Fitzgerald Professor at the University of Melbourne in 1990 – he told an untruth. His contract asked him to specify whether he knew of anything that would limit him in performing the duties of the role. “I ticked no, which was a lie,” says Houghton. He had failed to tell the university that he had the reading ability of a typical primary school child. He is dyslexic and he feared that if this was known it would cost him the job he aspired to.

What for most of us is second nature – turning a string of characters on a page into words and meaning – is a huge task for Houghton. When he looks at a written word, he sees and registers all the letters but he perceives them as a random arrangement. His brain can’t assemble them in the right order to form a word. So for him, reading every word requires solving a puzzle – it’s like playing a round of Scrabble in which random letters have to be correctly arranged. And he has to do this with every word of every sentence, in every paragraph of every page. He can manage to read a paragraph “pretty well”, he says. But a whole page is a challenge and reading a book is unimaginable.

To meet Houghton you have no idea of his reading difficulty. He’s engaging and a big personality – extremely knowledgeable, a lively storyteller and easy company. His secret weapon is his excellent memory. Not for things he’s read, obviously, but for things he’s heard. And he’s an expert at organising information in his head, rather than on paper. As an academic it was essential for him to give lectures to students and talks to conferences and seminars. He’s delivered thousands of them, largely from memory, using a minimum of notes. Amazingly, he has also written and published widely in international and domestic scholarly journals and served on a number of editorial boards.

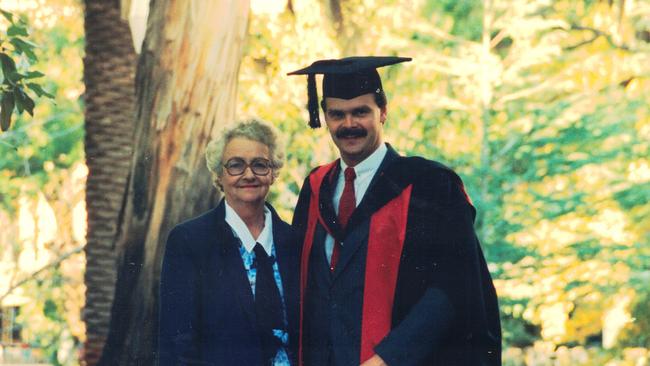

As a young man Houghton ticked all the boxes needed to embark on a prestigious academic career. He did his bachelor’s degree in commerce at the University of Melbourne – in his home town. He went on to a master’s degree at the London School of Economics, and his first job on returning to Australia was as a junior lecturer at the University of Western Australia, where he also completed his PhD.

In Western Australia he moved rapidly up the ladder to a full professorship while still in his early thirties and, at 36, he returned to the University of Melbourne where he was soon appointed as the Fitzgerald Professor – then one of Australia’s top posts in his field – only 16 years after he’d graduated there with his bachelor’s degree.

In all this time he had told nobody at the universities where he worked about his dyslexia – his inability to read anything longer than a few paragraphs. It was a secret which caused immense strain. He never knew when he might be missing something critical. “I had to explain away mistakes, but I wasn’t going to own up to why. I invented multiple excuses,” he says. The stress was constant. He not only had to keep up with the academic literature in his fields of accounting and economics, but he also taught courses, supervised PhD students and took an increasing role in university administration. All while disguising his lack of literacy. He put in “humungous hours” to compensate. “I became an archetypal workaholic,” he says.

Today the plight of those with dyslexia is somewhat easier. Although society still expects adults to be fully literate, there are also apps that translate voice-to-text and text-to-voice, and the advent of AI has made a huge difference. For example, AI can rapidly summarise a long document, giving a spoken word precis. Houghton now uses AI many times a day, and software that translates between text and voice is an essential tool for him. But he was born in the 1950s, and when he was growing up help came in a different way – through the selfless and dedicated efforts of his mother Betty.

Education was a big deal in the Houghton family. Both his parents came from less privileged backgrounds and were determined that their two sons would succeed educationally. Neither his mother nor father were dyslexic (though the condition can be inherited) and had no reason to think their children would be.

Houghton’s father, Allen, had the academic talent to attend Melbourne’s famous University High School but was denied, by family circumstances, the chance to go to university. He joined major retailer Foy & Gibson as an office boy. After volunteering for the army in World War II – where he fought in the Pacific and rose to become an officer – he returned to Foy & Gibson where he ultimately reached the top as managing director.

Houghton’s brother John, four years older, was smart and poised to succeed. He thrived at private boy’s school Camberwell Grammar, went to the University of Melbourne and graduated with an honours degree in history. Things were different for Keith, who followed in John’s footsteps at Camberwell. “It was like, ‘Oh, you’re the brother’,” he says.

Camberwell was a traditional school where boys were referred to by their surname. Seared in Houghton’s memory is one particular teacher who taught him when he was about 14. His habit was to pepper students with questions, such as “Jones, what do you think?”, “Fraser, what do you say?” Except for Houghton, for whom this teacher had a nickname. “I was referred to as ‘Dumb-Dumb’. You try and laugh it off and pretend it does not dig deep into you but I still remember it vividly. It was extraordinarily impactful.”

Years earlier, when Houghton had been finishing primary school, it was obvious to his parents that he was having major learning difficulties. In year six he overheard a conversation where his parents discussed sending him to the local technical school instead of to Camberwell. Today he sees it as an idea that had some merit. He’s always been good with his hands, and enjoys carpentry and cabinet making; it’s a hobby he’s kept up in adulthood, making a few pieces of furniture for the family home in the same way his father did decades earlier. But back then, influenced by his family outlook, he viewed the prospect of going to tech school as equivalent to utter failure. He says his tenacity kicked in. “I thought, ‘I’m not doing that’.” Thereafter his education was like riding a rollercoaster. He would lift himself with a huge effort, get past a key milestone, and crash utterly exhausted. “Then things would start to fall apart and I would lift myself again.”

His education was only possible because of his mother Betty’s dedication, and his own good memory. “She would essentially read me everything. She would only have to read things once, or at most twice.” She continued doing it through high school and through his bachelor’s degree. “She probably should have a degree from the University of Melbourne,” Houghton says. Betty was his champion. She pushed his cause at Camberwell where she met a lot of resistance. “Back then it seemed like they really didn’t think dyslexia and stupidity were different from each other,” he says.

Another problem was that, because he couldn’t easily read, he was a bad speller and his written work was poor. “My handwriting is completely indecipherable,” Houghton says. “It was deliberate. If you’ve got indecipherable handwriting, they can’t pick up the fact that you can’t spell anything.” But this did help him in written exams when the teacher would sometimes call him in to interpret his handwriting, giving him the chance to explain orally what he knew about the subject. “It was my ‘get out of jail’ card.”

Houghton never had a problem reading numbers. “I can see patterns in numbers which other people can’t,” he says. He is very good at quantitative thinking – which is why he later succeeded at economics and accounting – and was fine at answering questions that were expressed mathematically. But maths questions are often written in words, rather than just in mathematical notation, and these tripped him up. His most anxious time in school was year 12 when he sat the public exams, and there was no opportunity to interpret his handwriting to the markers. “I really didn’t know whether I’d bombed out completely. But, for whatever reason, I passed.” Well enough to get over the next hurdle – entry to the University of Melbourne’s commerce degree.

Houghton always found ways to cope. During his degree, as well as the help from his mother, he had a group of close friends he studied with. When he went to London for his master’s degree and lost direct support from Betty, a close friend read him material and proofed his written work.

For his PhD he deliberately chose a data-rich topic that played to his strengths. He did most of the research using something then very new in academic research – a mainframe computer which was available in the wee hours of the morning. It meant that the reading requirement for his PhD was minimised. “I got away without a big literature review because it was new and different and quantitative,” he says. His draft thesis was proofed by his wife, who corrected his spelling.

Yet his dyslexia continued to be a problem as his career developed. “I was not as prolific [at publishing research] as others,” he says. “Pretty much everything had to be co-authored. For reasons that are obvious, I wasn’t good at reading the literature.” When he was asked to examine a PhD thesis – usually hundreds of pages long – he would “lock himself away for a couple of weeks”.

Even worse, there were times at the University of Melbourne when, as deputy dean, he had to read the names of hundreds of graduates as they were presented with their degrees at the graduation ceremony. “It was hell,” he says. His work-around solution was to memorise the names. “I had to learn them as best I could. It took me four days typically, which was four days that were completely unproductive.” Even then he got some wrong.

Houghton was by now in his forties, holding an esteemed academic position. He was listed in Who’s Who and he had nothing really left to prove. But he was still not ready to publicly acknowledge his dyslexia. Then something happened that changed his life. In 2000 he was the faculty representative on a university-wide committee which met periodically to determine the fate of students whose academic progress was not satisfactory. Before them was the case of a student who, after multiple failures in second year, was facing the termination of his enrolment. It wasn’t clear what had happened, because he had done well in his first year. The student was there in the hearing and at the end the chair asked if he had anything he wanted to add. Houghton remembers the student saying: “Look, my mother got seriously ill, and she was my eyes and ears, and I haven’t been able to have that support that I’d had.”

The story instantly resonated with Houghton. He told the committee chair it was “significant new information” that must be considered. The student then explained everything. He was dyslexic and his mother had read him his course material until her illness left her unable to continue. The student was allowed to continue his studies and the university offered him support for his dyslexia.

Houghton then asked himself: “If this 19-year-old kid has the courage to do this, what’s wrong with me?” So he decided to out himself. He spoke to journalists. Stories appeared in the media about his dyslexia. And he discovered that many families with a dyslexic child wanted to know more. “I spent Thursdays for much of the next year talking with mothers and sons and the occasional father, the occasional daughter. Essentially I was saying that universities are not insurmountable even if you’ve got dyslexia. You can achieve. So give it a go.”

In 2002 Houghton climbed another rung on the academic ladder, becoming dean of business and economics at ANU. This time he fully disclosed his dyslexia in his application for the job. It turned out it wasn’t a problem. The university also offered to provide someone to read out the names for him at graduation ceremonies. “I could relax, and it was enjoyable. I got to celebrate with the graduating students for the first time,” he says. He was appointed chair of the ANU’s equity and access committee, a satisfying role that enabled him to do more for students and staff with learning difficulties.

Houghton also became patron of the Victorian chapter of SPELD, an assistance and advocacy body for those with specific learning difficulties. He served for many years alongside the late Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, who was also a patron. SPELD Victoria president Deirdre Hardy says 5-10 per cent of people have a specific learning difficulty, with dyslexia being the main one, and the organisation’s work includes making assessments of children with learning problems and advising on their needs.

Dyslexia presents in different ways. Houghton’s inability to order letters is one of them. For example, he can’t distinguish between “saw” and “was”. Other people with dyslexia may, or may not, have Houghton’s inability to put the letters of a word in order. A different problem that some dyslexics have is in distinguishing similar looking letters such as “p”, “q”, “d” and “b”. The word “press” becomes “dress”, or “pack” becomes “back”.

Australia doesn’t have many schools where learning is specifically designed for dyslexic kids. There’s a prevalent view that dyslexic children are better off being “mainstreamed”, unlike in the US where there are dozens of specialist schools. Houghton particularly admires the New Community School in Virginia. “They offer a tailored curriculum for students with dyslexia and produce remarkable results – all without relying on mothers for full-time support,” he says.

Betty, who passed away in 2002, saw the beginning of this new phase of Houghton’s life – his transformation from a secret sufferer to a public advocate for his learning difficulty. Houghton is extremely grateful to her. Without her love and her dedication to his education, he wouldn’t have come close to completing high school, let alone have had a long and distinguished academic career. He way outperformed everybody’s expectations.

His brother John’s experience was very different. He was an academic star at school and university, but when he graduated, Australia was drafting its young men to fight in Vietnam. To delay the draft John added a diploma of education to his honour’s degree, and became a high school teacher. “He came to hate it,” Houghton says. But neither did he move to a job that offered more satisfaction. He finished his career in a middle management role in TAFE. It was clear that he was unfulfilled but neither Keith, nor his parents, realised the depth of John’s suffering.

In 2020, after months of Covid lockdown, without warning John took his own life. His diary revealed that he blamed his mother, and Keith, for much of his turmoil. He was jealous of the time and attention that Betty had given Keith to overcome his dyslexia. In one diary entry John said that his first four years, before Keith was born, were the only years of his life worth living. The knowledge that Keith, with his learning difficulties, became a professor while he, despite his academic talent, did not, clearly hurt John. After his death, one of his friends recalled him saying, “Oh, you know I’m smarter than my brother.”

“Reading his diary was overwhelming,” says Houghton. It became clear that his mother’s love, which seeded his success, was perceived by John as a major cause of his life’s difficulties.

After John’s death Houghton went through a period in which he wondered, “Maybe I didn’t show my love to my brother enough.” There were other unanswered questions. Did the diary reflect his brother’s true state of mind at the time? Perhaps it exaggerated things, serving as a release for his frustrations.

Regardless, it’s a bitter irony that his mother’s dedication to him, to which he owes so much, was seen by his brother as parental betrayal. It’s become clear to Houghton that a condition like dyslexia has wider consequences that radiate outwards, like ripples in a pond, affecting far more people than the one who is diagnosed with it.

Apart from the effect on his brother, there was also the impact on his immediate family of the years of hard work and the long hours he spent to achieve academic success.

The economist in him also counts up the cost of dyslexia to society as a whole. For example, data on US prison populations show a disproportionate number of dyslexics. “The cost of not supporting students, and indeed adults, with dyslexia is huge and pervasive,” he says.

Although he continues to do research work during his formal retirement, he’s given up being a workaholic. He now consciously puts his loved ones first. “If I get a work-related call when I’m in conversation with any of my grandchildren, I let it go to voicemail,” he says.

He also sees that he was driven for most of his life by the need to make up for the lack of self-confidence, which sprang from his dyslexia. Today he shares these insights in the hope that it helps other people with learning difficulties to avoid what he went through.

“For parents, I offer two observations. Don’t ever give up on your son or daughter. They are different, not ‘dumb’. And don’t ignore the pressures which are placed on siblings,” he says.

“And for those individuals with dyslexia, the most important advice is don’t give up on yourself. The way you navigate the world of words may be different to others, and you may find that you have strengths in other aspects of your life that others don’t. There is hope and there are people who care about you even if, right at this moment, you don’t care about yourself.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout