Karin Keays on husband Jim Keays, Masters Apprentices and the loss of her son

My life with Masters Apprentices frontman Jim Keays was exciting and glamorous – but we endured unimaginable tragedy too. One from which our marriage never truly recovered.

There are places on this Earth where I have felt so close to heaven that I could almost touch it, hear it, see it. The Lake District in England, one early autumn day in 2013, was among them. I was high on a fell (the Lakeland word for hill), near the summit. There were many trees, mainly rowan or “mountain ash”, laden with red berries and blackbirds. It was beneath one of those trees that I lay; before me was a breathtaking panorama of lake, forests, fells and sky. Clouds formed and reformed. Sometimes patches of blue allowed golden sunrays to spotlight distant hillsides and fields for a few moments before turning the steely water of the lake to a glittering ribbon, then moving on again. This is the land that inspired the great Romantic poet William Wordsworth. It is the place where Beatrix Potter lived, wrote and illustrated her much-loved stories of Peter Rabbit, Samuel Whiskers and Mrs Tiggy-Winkle. To this day, it is a honeypot for artists, tourists and outdoors types.

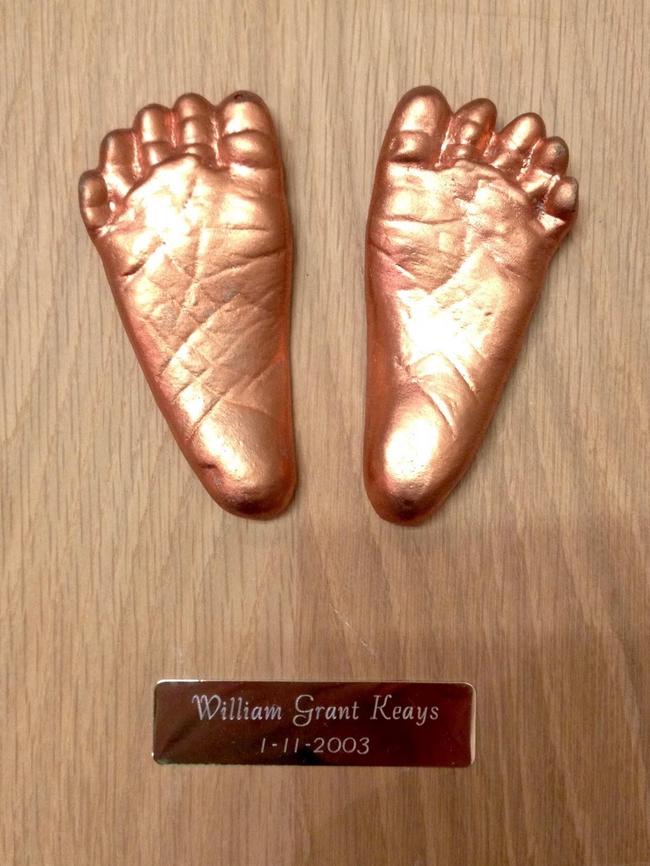

An unfamiliar peace settled deep in my heart. Just inches from the crown of my head lay a small posy of flowers and holly leaves, handpicked from the garden of my adored late father-in-law Sam. Two years ago, I carried Sam’s ashes to this same place and sprinkled them beneath the tree where the ground would not be walked on. It was the last thing I could do for a good man who loved me and whom I loved in return. Now I lay back on the soft grass having just sprinkled the ashes of my baby son, William, beneath the same tree. As I looked up at the sky through the leaves, my thoughts touched lightly on the myriad changes in my life; then, as thoughts do, slipped back in time to one September day many years earlier.

It was 1988 and I was manager of a Gold Coast store for a national fashion retail chain. I was 23 years old and nursing a broken heart. My best friend Snezana suggested I move to Melbourne so we could be together, work hard for three months, and save enough money to live our dream and travel the world.

I asked the question at work and was told there would be a position waiting for me in a city store in Melbourne. Now all I needed was a short-term rental. My only prerequisite was a garage for my car, a brand-new Ford Laser in Monza Red. Snezana is a can-do powerhouse sort of girl, always has been, and she had been on the lookout for me. A couple of weeks before I was due to leave the Gold Coast she called to say she had the perfect place for me – a huge house owned by a ’60s rock star. His name was Jim Keays, from a band called Masters Apprentices. “I’ve never heard of them,” I said.

Privately, I was thinking she must have been exaggerating about the rock star part. I love music and was pretty certain I knew all of the big Australian bands. “Masters Apprentices?”

Snezana could not believe it. “How come you’ve never heard of them? They were huge.”

“Maybe… tell me one of their songs. How does it go?”

“Their biggest one is Because I Love You and it’s on the new Lee Jeans commercial,” she said. She started singing down the line, “Do what you wanna do, be what you wanna be, yeah…”

I could tell she expected me to realise I knew it, but I hadn’t seen the commercial or heard the song. “I don’t know it, sorry. Just tell me, does this place have a garage?”

Snezana’s sound of frustration was hilarious. “Yes! It has a double garage for your precious car so you can pick your spot.” Sounding mystified and incredulous, she mused, “I can’t believe you don’t know that song.”

“Oh well,” I said, “I’m going to be there for three months so I’m sure I’ll get to know it.”

A few days later, Snezana called to say she had arranged for me to meet Jim and see the house on the day I arrived in Melbourne. “Can you get here any earlier? They’re filming the clip for their new single and looking for a girl with long dark hair, just like you,” she said. “You would be perfect.” It sounded exciting and tempting but I couldn’t let my employers down, especially as they had been so good about finding a job for me in their Melbourne store.

Ironically, it was on the night before I met Jim that I first heard Because I Love You. It was the second night of the long solo drive from Queensland. I had booked into a motel in Jerilderie, near the NSW/Victoria border. In the room, I turned on the TV and the Lee Jeans commercial caught my eye. That was the first time I heard the song that would be the soundtrack to the next 26 years of my life with Jim.

Within 24 whirlwind hours, Snezana and I were walking in darkness up the path to Jim’s front door. We passed an older couple on their way out. Snezana said hi to them and told me they were Jim’s mum and stepfather, Nancy and Sam. I couldn’t really see them in the darkness and didn’t think too much of the event as it unfolded. Yet here I was, at the front door of my future home, about to meet my future husband, bumping into my future parents-in-law and standing beside my soul-sister Snezana. And my main concern was still my beloved car. I fancy the universe looking upon that scene and taking a cosmic snapshot – click – of a moment in time when soul paths converge at the one pivotal point to change the course of history.

The house looked nice, from what I could see in the darkness, with a double garage to the left. Perfect! Suddenly, I felt nervous standing there on the porch as the doorbell rang. What if he didn’t like me? The door opened and there stood a man in green pixie boots. Pixie boots! I suppose I had been expecting a ’60s singer to look like an old hippie, but this guy looked more like my all-time favourite music idol, Rod Stewart, crossed with a member of Status Quo. More ’70s rocker than ’60s hippie. Snezana introduced us. To my dismay, Jim was almost offhand and after we all went into the lounge room and sat down, I realised he was virtually ignoring me. The conversation bounced around but Jim never looked at me or spoke to me, almost to the point of rudeness. After a while, he left the room to go upstairs and dress to go out. Snezana went with him. I heard her call my name, so I went in search of her and found her in the foyer. The house was sprawling, with four bedrooms, a study, four reception rooms and three bathrooms. The colour scheme was a very ’80s palette of palest pink and honey brown, which I liked. Snezana asked me what I thought of the house, and I replied, “It’s great but I don’t think I’ll be living here. I get the feeling Jim doesn’t like me.”

Snezana looked at me in utter disbelief. “Are you kidding?” she half-whispered, “We were just talking about you, and he thinks you’re absolutely gorgeous.”

Part of me wondered how I could have got it so wrong. Another part of me wondered how he could even know what I looked like when he had barely glanced at me. Later, Jim would tell me that he was pole-axed when he opened the door because, for him, it was love at first sight; he waggled his fingers at me like a magician casting a spell and said, “You were so stunning, I didn’t know where to look. Couldn’t you feel the electricity in the air? It was all around.”

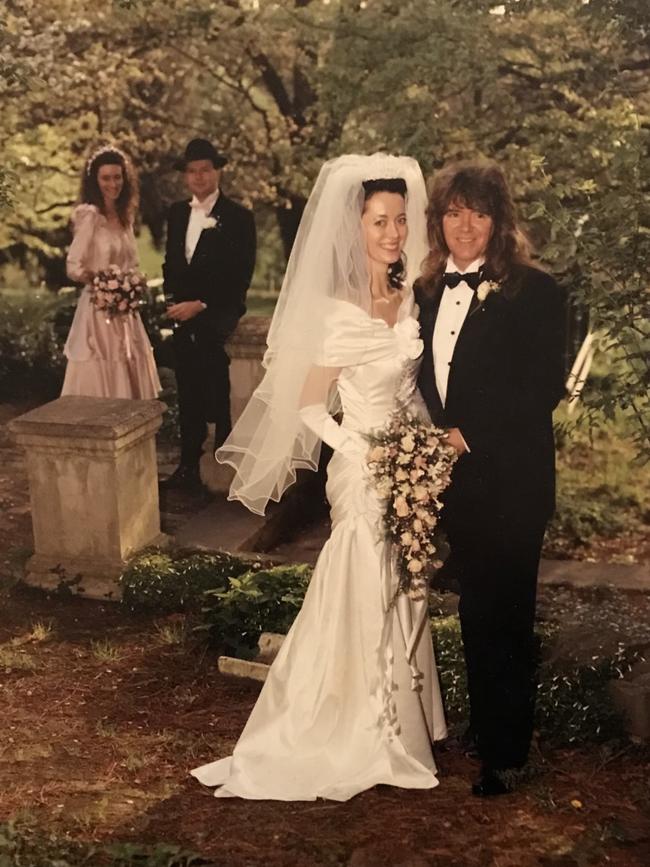

We were married in the spring of 1989 at Montsalvat, an artist colony set in idyllic grounds outside of Melbourne. Built in the 1930s from local stone, Montsalvat could be a medieval village in the French countryside. Our wedding was held in the chapel and the reception was a medieval-style banquet in the Great Hall. Some aspects were traditional, and others were very definitely rock and roll. We’d hired a jukebox for dance music and it was set up in the Great Hall. For our bridal waltz, we’d chosen the Mink DeVille song So In Love Are We. Jim had brought along his vinyl album with the song on it and he’d arranged for it to be played on the record player at the venue, which we tested in the days prior and was working perfectly. When the time came for us to take to the dance floor, we stood waiting a few moments only to be told, “It doesn’t work. The needle’s stuffed.” Quick as a flash, our friend and guitarist, the inimitable Wayne “Morry” Matthews, jumped up and crossed to the jukebox, calling out, “Don’t worry. I’ll pick something.” Jim and I, who were already nervous enough about dancing in front of our friends, looked at each other in trepidation and then laughed as the first notes of Because I Love You filled the Great Hall. It wasn’t what we’d planned but, in retrospect, it couldn’t have been more perfect.

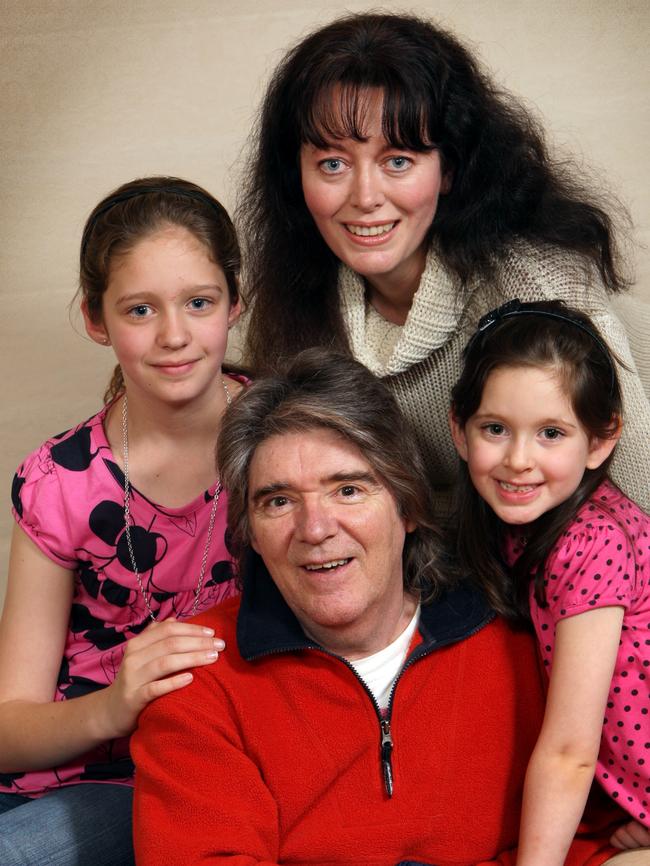

We lived our marriage mindful of each other’s happiness, being all for one and one for all. Two people with shared goals, working towards them as one, while supporting each other in our personal goals and trying to make the other happy. We were blessed with our beautiful daughter, Holly, in 1995. We welcomed another beautiful baby girl, Bonnie, in 2001. We had a thriving family business, a close circle of friends, and the means to travel regularly to visit extended family. Jim had recorded a solo album, Caledonia, but was so busy performing with Darryl Cotton and Russell Morris in the supergroup Cotton Keays & Morris, and the stadium tour of Long Way To The Top, that there was no opportunity to release it. In 13 years of marriage, we had faced our share of life’s hardships and challenges together. We had worked hard to be in the position we now found ourselves and we did not take it for granted. Jim and I had much to be thankful for, and we knew it.

Christmas drinks at our place in mid-December 2002 saw the house filled with more than 100 friends, neighbours and musician-types spilling out into the garden or kicking back on the verandah. The Christmas decorations were up, lights twinkling. By 7pm, the lounge room looked like Santa had already been with masses of brightly wrapped gifts piled beneath the Christmas tree. It seemed as though everyone who walked in the front door left something under the tree on their way through to the kitchen. When I look back on that time, I think of it as the end of the age of innocence for our family.

Early in 2003, Jim left on the regionalLong Way To The Top tour – only to arrive home again unexpectedly a few days later for a short interlude. The first time we made love, I looked across at Jim afterwards and smiled, teasing him about not using contraception. Jim grinned back and said, “We might have a baby.”

Holly had been born 11 days overdue. Bonnie was two weeks overdue. It was some weeks prior to my due date with William that the obstetrician first raised the potential of induction. His actual words were, “I won’t let you go two weeks over this time, Karin.” I questioned him about why and he said because William was a big baby, and a boy, and he was worried about shoulder dystocia. He also mentioned my age (I was 38) and the potential for problems with the placenta. Jim and I were concerned enough to make another appointment with the obstetrician to question him further. With induction a very real possibility, I researched Syntocinon, a synthetic oxytocin used to induce labour. Had this been happening today I would have found numerous references online to foetal distress during artificial induction but, in 2003, I didn’t find much information.

William was four days overdue when I was booked into hospital on November 1, 2003. I arrived at 8:30am and induction of labour commenced with an amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes). William’s heart rate was normal when, at 2pm, I was given intravenous Syntocinon. William’s heart rate plummeted and an emergency caesarean was performed just before 6pm. But it was too late. I waited to hear a gurgle or a cry. No one spoke and I whispered to Jim: “Can you see him?” Jim just shook his head; he put his head on our clasped hands and I felt his tears. William had been born with no heartbeat, pulse or vital signs, but was revived in the operating theatre. He lived for six and a half hours.

In the weeks after William’s birth, death and funeral, we started asking questions about his care and treatment and the monitoring of my labour. There were no answers that were satisfactory to us from the obstetrician or the private hospital. I requested a police investigation into what we believed was 45 minutes of missing CTG trace (a continuous record of the baby’s heart rate and the mother’s contractions during labour) and disputed medical records. Had it been a workplace death or a road death, there would have been a specialist police investigation.

We requested and were eventually granted an inquest, but the coroner’s finding in August 2008 made it clear there would be no criminal investigation.

If I had my time over again, knowing what I know now, I would trust my body and my history of giving birth to Holly and Bonnie. I would find a registered independent midwife, maybe along with a doula, and give birth at home. I hear you ask, “What if something went wrong?” Well, it couldn’t go more wrong than it went at the private hospital with a private obstetrician, could it? After listening to all the testimony presented at William’s inquest, I have come full circle to the same conclusion that I began with. Without the use of Syntocinon, I can see no indisputable reason why William’s birth would not have been as straightforward as Bonnie’s and Holly’s.

Had homebirth been unavailable to me, or too expensive, I would go only to a Level 3 public hospital with resident paediatric and anaesthetic staff, on-call access to a senior obstetrician and a dedicated obstetric theatre. (Level 1 is private hospitals, like the one where I gave birth to Bonnie and William, with no resident staff, where care in labour was given by midwives working shifts and visiting medical staff.) I would not, under any circumstances, agree to artificial induction. From what I heard at the inquest, if a mother or baby has a diagnosed obstetric or medical condition, then artificial induction of labour by Syntocinon would not be indicated. Logically it follows that if there is no diagnosed medical condition, then any suggestion or recommendation to the mother to undertake artificial induction of labour, along with all the associated risks involved, would be a matter of personal choice rather than medical necessity.

One night in mid-2013, I woke with a jolt in the middle of the night. Turning on the bedside lamp, I looked at the wardrobe opposite. On the top shelf, hidden at the back, was the tiny box that contained William’s ashes. For 10 years it had been with me, always close to me, because what do you do with a baby’s ashes? He’d never been anywhere, never known anything but the safety of my body until his horrific death. I wouldn’t put him alone in the cold ground of a strange cemetery.

It was the only thing I ever worried about when I left the house. I worried that if there was a burglary, thieves might prise open the box and scatter the ashes. The girls knew that William’s ashes were to be scattered with mine in a place of their choosing when I died, but until then, the tiny box of his mortal remains stayed close to my bed.

That night I had an epiphany. William’s ashes needed to be with those of Sam, his grandad who loved him, until my time came to join them. Not only did it feel right, it felt urgent. The next day, I could hardly wait to tell Jim. I wanted to be sure that he was OK with our son being laid to rest on the other side of the world. I told him about the feeling that had woken me in the night and how important it felt to me. Jim looked at me quietly, then he said hesitantly, “Do you think it would be a good place for me, too?” Jim had been diagnosed in 2007 with multiple myeloma, which we were told was an incurable blood cancer. Back then we didn’t even know if he would still be alive in a year. He was put on dialysis and chemotherapy, then had stem-cell transplants, and continued to perform with Cotton Keays & Morris. For the next seven years, he’d had short periods of remission.

By late 2012, Jim and I had separated. Even now writing those words, I struggle to believe it, and the story of how our marriage had come to that point is a book of its own. The five years since his diagnosis had seen personality and behavioural changes in Jim that were the result of the high doses of steroids he took as part of his medical treatment. Prior to beginning the steroids, Jim and I had been as one in our quest for justice for William and change for the wellbeing of future babies. Most distressing of all, he would say things like, “I don’t want some other guy getting all my money.” When, I wondered, had our family home and business – all that we’d sacrificed and worked for together as a team, all for one and one for all – become Jim’s and not ours? It was as though there was an evil entity whispering words of poison in his ear.

Despite the machinations of self-serving others our true love did not die, and in our hearts, neither did our marriage. From the day we separated and eventually divorced, until Jim died on June 13, 2014, we never lived more than 10 minutes away from each other and I was still his primary carer. Jim would always be the love of my life and the father of our children, and I cared for him because I wanted to. I cared for him because I love him.

Jim’s cancer diagnosis and long illness overlapped with William’s story, and I kept wishing I had known beforehand what I learned the hard way. What began as a story written to help grieving parents changed shape almost of its own accord and became something greater. This book began as William’s story – what happened, and what I learned along the way – but life did not stop unfolding. Our children, Holly, Bonnie and William, were born out of great love and William’s story could not be told without first telling the story of that love.

Edited extract from It’s Because I Love You by Karin Keays, paperback/ebook @karinkeays.com