Jane Harper: Murder, she wrote

Three bestsellers in three years, a film in the works — Jane Harper quit journalism to write Australian thrillers and struck gold.

It’s a tiny room, so bare it’s almost ascetic. Four blank walls, a desk and computer. A solitary chair, discouraging visitors. It sits above an empty shopfront in a squat, taupe building on a back street in St Kilda. A single window frames an uninspiring view of a brick wall. This is Jane Harper’s office and it is from this workaday post that the English-born, Melbourne-based author sets her imagination free. Off the leash, it roams the far horizons of her adopted homeland, mustering atmosphere, lassoing detail, capturing the soul of the Outback in all its heat-struck, bleached-sky glory. She uses the landscape to ratchet up suspense; vast, harsh and menacing, it’s a thrumming constant, stretching intricate plots taut. Then she spins the whole into murder-mystery gold.

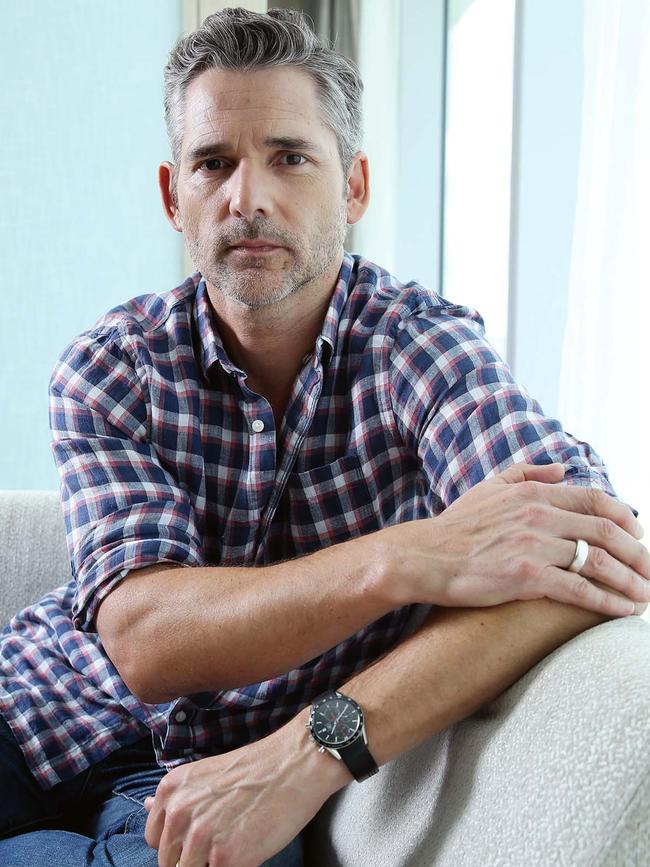

Harper’s debut novel The Dry, a tightly wound page-turner set in a parched Victorian farming community, became the literary phenomenon of 2016, sparking an international bidding war before landing Harper six-figure, three-book publishing deals in Australia, Britain and the US. Right now, hundreds of kilometres north-west of Harper’s austere garret, in Victoria’s Wimmera region, actor Eric Bana is creating his version of loner cop Aaron Falk, The Dry’s protagonist, for a movie adapted and directed by Robert Connolly (Balibo, Paper Planes). Reese Witherspoon’s production company snapped up the film rights even before the book was published, because that’s the kind of dream run the 39-year-old former Herald Sun journalist is having.

The Dry has sold more than a million copies worldwide and Harper’s next two books, Force of Nature and The Lost Man, have also become bestsellers, shifting an additional 600,000 copies. Hollywood is circling those too. “Book by book, she’s creating her own vivid and complex account of the Outback,” critic Charles Finch wrote in The New York Times upon the US release of The Lost Man in February.

The books have been translated into 36 languages; rows of shelves crammed end to end with foreign editions ease the severity of her office décor. “Contractually, they send me boxes of translation copies and I haven’t quite worked out what to do with them all,” Harper says, with a bemused shrug. The stacks are set to keep growing — Bulgaria has just come on board — and there’s a fourth book underway, another Australian mystery to meet the clamour of her swelling fan base, which ranges across demographics and borders, from Norway to France, Russia to Korea.

Harper writes with monastic dedication. The bayside apartment she shares with her husband, journalist Peter Strachan, is small and has a toddler in it: daughter Charlotte, born in 2016 between mum’s first and second bestsellers. Hence the nearby work space, where Harper keeps office hours. Clock in. Clock out. She sits by the window but looks only at the screen. No visitors. No checking email. Just epic bouts of planning, mapping each thriller’s terrain so she knows exactly where the chapters will begin and end, and then one word after another until she reaches 90,000. No indulging writer’s block. No self-doubt. Three bestsellers in three years. It’s as mundane and miraculous as that.

“In the time I’ve known her, she’s always been brilliant at carving out amounts of time and doing something useful with them,” says Strachan, who married Harper in 2015, on the very day her debut novel went to auction. “She’s of the view that you can learn to do most things, if you apply consistent effort.”

It’s now part of Australian literary lore that Harper “learnt how to write a novel” by completing a 12-week creative writing course online while working full-time as a business reporter. She’s much too polite to say so, but there’s a sense that she resents the way this is viewed as somehow cheating by all those wannabe authors waiting for the muse to make a house-call. As if she wrote a bestseller in the same join-the-dots way she’s also learnt dressmaking, piano and ballroom dancing. As if being practical, efficient, technically proficient and disciplined counted for nothing. Of course, writing is easy. As the old saw goes: “All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

If Jane Harper were to skive off writing for the day, hop on the vintage rollercoaster on the St Kilda foreshore and ascend rapidly to its first joyous peak, hovering high above the choppy waters of Port Phillip Bay in a bubble of exhilaration, the expression on her face might approach the one it wears now. Her shining-eyed excitement is a relief, frankly. If she was blasé or cavalier about her considerable success, it simply would be too much to bear. Harper’s also refreshingly free of ego; her genuine humility is spoken of in publishing circles with something approaching awe.

We’re sitting in a quiet restaurant in the shadow of that rollercoaster while she talks about the movie and the “perfection” of Eric Bana’s casting. She visited The Dry set recently but has been sworn to secrecy on details, including its location. (Local reports have Minyip, in the Wimmera, standing in for the novel’s fictional town of Kiewarra.)

Harper was working at her desk at the Herald Sun in October 2015 when her agent, Clare Forster of Curtis Brown Australia, called to tell her she’d hit the literary equivalent of the jackpot. It was early morning and the newsroom was quiet; the building’s dodgy phone reception meant Forster’s voice came through in fits and starts.

“Reese Witherspoon wants to option your book.”

“What?”

“Reese Witherspoon.” Forster was standing on a busy Melbourne street corner screaming the name of the Hollywood star into her phone as passers-by stared.

“Who?”

“I had to get her to repeat it a couple of times,” Harper laughs. “It did come completely out of the blue; I didn’t know it had been put to them or they were considering it or anything.”

Los Angeles-based agent Jerry Kalajian had put the manuscript in front of Witherspoon and Australian producer Bruna Papandrea following their success with screen adaptations of Gone

Girl, Wild and Australian author Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies.

“[Bruna] emailed me that night saying, ‘I’ve got sandbags in my eyes but I can’t put this down’,” Kalajian says on the phone from LA. Witherspoon also sped through the gripping tale of a city cop returning to his drought-stricken rural home town to investigate a murder-suicide involving a childhood friend.

She recommended the book to her millions of Instagram followers and instantly bought the rights.

Kalajian works for the Intellectual Property Group, a major Hollywood player behind page-to-screen smashes such as Million Dollar Baby, Life of Pi and True Blood. He’s a big booster of Australian content — his slate includes Moriarty, Tim Winton and Markus Zusak — and he knows he’s onto a winner with Harper. The Dry “just blew me away”, he says, adding that the way such a distinctively Australian story has translated across borders is “phenomenal”.

“The beautiful thing about the way she wrote that book is that you actually broke out in a sweat as you were reading it,” Kalajian says. “You can feel the heat of the Australian interior.” The same is true for her evocative third book, The Lost Man, which is set on a cattle station in outback Queensland and focuses on three brothers, one of whom is found lying dead in the middle of nowhere, near an old gravestone. Kalajian is currently fielding offers for the film rights from interested parties in the US, UK and Australia. Because Force of Nature also features detective Aaron Falk — he searches for a female hiker missing during a corporate team-building course in remote bushland — Witherspoon owns character rights to that one, too. And so Harper is, as Kalajian says, “off to the races”.

When Harper decided, at the age of 34, to finally chase her childhood dream of writing a book, she had no expectations beyond finishing it. “I’d always thought, ‘One day I’ll do it’ but it became apparent to me that this one day was never really appearing,” she says. “I never seemed to find the time and I found it very hard to find the motivation to make such a big commitment and effort for such uncertain rewards.” She put aside all the paralysing thoughts — Will it get published? Will people read it? Will they like it? — and set about creating the kind of strongly plotted, character-driven thriller she’d always enjoyed reading. “That was the mental switch I needed to make,” she says, “to thinking, ‘I’m just going to write a book that I enjoy working on and it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t get published’.”

She signed on to do a novel-writing course through an offshoot of the London branch of literary agency Curtis Brown, more to set herself the external pressure of a deadline than anything else. As a journalist, she says, she “quite likes deadlines”. Three months later, writing for an hour before and after work every day, she had a rough draft of The Dry. Harper is keen to play down the impact of this course, discussion of which crops up in every interview she’s done since. “I learnt a lot; it did focus my attention,” she says, her forehead creasing slightly. “But it was 12 weeks and when I finished it I wrote two more complete drafts, then I went through the whole editing process, then I wrote two more books. And I’d been a print journalist for 13 years, writing every single day, so I had a lot of the writing technique and discipline that came into play later.”

Harper entered the final draft in the 2015 Victorian Premier’s Unpublished Manuscript Award and won. Even sweeter than the $15,000 prize was the stream of emails suddenly pinging into her inbox from publishers and agents keen to read her debut.

The quintessentially Australian flavour of her prose suggests Harper has been absorbing the heat and emptiness of the Outback through her pores since birth. She was, in fact, born in the industrial city of Manchester, England. At age eight, she migrated to Melbourne with her parents and two younger siblings; six years later they returned to England, eventually settling in North Yorkshire. Her parents were prodigious readers of blockbuster crime novels and the house was filled with books. “I read the standard childhood titles, nothing too highbrow or out of the ordinary: Roald Dahl, Sweet Valley High, The Baby-Sitters Club,” Harper says. “Sometimes I think people can be a bit snobby about it but you read what you enjoy reading.” Later, she moved on to thrillers by Lee Child and Val McDermid; Child’s debut, the Jack Reacher novel Killing Floor, remains a favourite.

Harper wanted to be an author but her practical side urged her into journalism, and after university, she started work on the weekly Hull Daily Mail in East Yorkshire. Australia called to her, however, and she started applying for jobs, eventually landing at the Geelong Advertiser, where she worked for three years. In 2011, she moved to Melbourne to begin work as a finance reporter on the Herald Sun where, her colleague Karina Barrymore says, she excelled at “cutting through the jargon and putting things into plain words for our readers”. She was always a good planner, “very organised”, Barrymore says. “She and her husband learnt ballroom dancing and it just started out as a thing they would do together but soon they were really high-achieving ballroom dancers. And then she decided she wanted to be a dressmaker, so she took herself to a course, learnt how to do it. She’s a really practical person. Nothing’s too difficult: ‘Of course everyone can learn this. Just do it’. ”

Her pragmatism was inspiring. Soon Barrymore had written her own crime novel, entered it in the Victorian Premier’s Unpublished Manuscript Award, where it was one of three finalists, and landed a book deal. Truth Untold, published under the name Karina Kilmore, will be published by Simon & Schuster next year.

Harper is generous with advice and encouragement. At book events and panel discussions audiences hang on her every word, thrilling to the notion that they too could become a globally recognised creative force with a little application. In a TEDx talk last October, she attempted to demystify the process: “The expectation is that you should wake up one morning with this amazing idea, fully formed, and you execute it in a passionate frenzy and anything less than that is seen as a less than authentic experience,” she told a rapt audience in her clipped English accent. Like anything, she insisted, creativity can be improved through training and practice.

“It’s not like I have this huge treasure trove of ideas in my mind,” she says now. “It’s more that I sit down and try to think what could I write about and then I think of one kind of hook.” Often, she’ll start with the resolution and work back from there, taking up to four months to painstakingly assemble the scaffolding of the plot before getting down to “the fun part” of writing. “It doesn’t feel like a formula to me,” she says. “It’s more about being honest with yourself about what you need to do. Writing a book is a huge task and to get from word one to 90,000 you’ve got to have some stepping stones along the way. Just hoping you get there with no kind of action plan is kind of unrealistic.”

Harper quit her day job in March 2016 when she realised she wasn’t going to be able to fulfil her book commitments while working full-time. She was also three months pregnant with Charlotte. It was hard to step away as she’d loved being a journalist, but she took some valuable lessons with her. Years of interviewing had given her an ear for authentic dialogue, and her early work on small-town newspapers honed her understanding of how tight-knit communities work. “All those years of speaking to people about an issue that can often on the surface seem quite minor, but then in talking to them you can see how deep that can run, and then trying to translate that in a way that people who aren’t affected by it can empathise with, it’s such a valuable skill,” she says. “I hadn’t appreciated at the time just how well it would lend itself to fiction.”

She’s also held firm to this timeless directive: grab the reader’s attention early and hang on to it for as long as you can.

The Lost Man opens with the stark image of a corpse curled next to a grave beneath a cruel desert sun. A circular pattern in the dust indicates the dead man spent his last desperate hours following the shade cast by the headstone as the sun crossed the sky. How’s that for attention-grabbing? Once gripped, readers find it near impossible to extricate themselves from Harper’s propulsive plotting, often winding up, like Witherspoon, with “sandbags in their eyes” at 2am. It’s the bibliophile’s version of a Netflix binge.

In an increasingly homogenised world, singularity of place becomes a drawcard and few settings lend themselves to great crime writing like the unforgiving emptiness of the Australian Outback. “I pick settings that are isolated because it forces the characters to react and interact with each other,” Harper says. “And I always try to make sure the setting is woven throughout the book so it’s not just the backdrop — it actually drives the characters’ behaviour and influences who they become. Australia is great for these kinds of novels; it’s beautiful but brutal. Things can go wrong quite quickly.”

Harper’s first two books were set within a day’s drive of Melbourne, but the third required some old-fashioned shoe-leather research. She flew to Charleville, 745km west of Brisbane, and then drove another 900km to the tiny outpost of Birdsville, on the edge of the Simpson Desert. Retired Birdsville police officer Neale McShane, who once patrolled an outback area the size of Britain, accompanied her on the drive: 11 hours on a dead-straight road, during which they encountered only 15 cars. McShane was peppered with questions the entire way and subsequent interviews with residents of this hardscrabble corner of the country helped Harper with the spare but vivid descriptions that characterise her novels. “Through observation and economy of style she leaves room for the reader to imagine it for themselves,” says Forster. “And it’s really struck a chord around the world.”

Crime writing has evolved in recent years, breaking the bounds of genre fiction and knocking at the door of literature. Harper is part of a new breed of mystery writer who trades in psychological insight and strong character development, along with intelligent, subtle prose that elevates it beyond the churn of the police procedural. Barrymore, Harper’s colleague on the Herald Sun business desk, is also that paper’s books editor. “I’ve really noticed a difference in the last five years and I think that’s because there are more women writers now,” she says. “Crime is not that hard-boiled, horrible male-centric story that is almost like victim voyeurism. It’s cleverer writing and Jane fits into that very well.”

Some authors, JK Rowling most famously, insiston being deeply involved in the film adaptations of their books, from casting decisions to final approval on script, location and director. Harper is not like JK Rowling. Beyond a stickybeak set visit — “I thought, ‘That doesn’t happen every day, why not?’” — she is leaving The Dry’s creatives to get on with it.

Not that she couldn’t hit the heights in Tinseltown if she chose to. “She’s learnt this process so quickly,” marvels Kalajian, her Hollywood agent. “Not only has a seasoned journalist morphed into an international bestselling author but now she’s got a real handle on the development process of her properties. She could also evolve, easily I think, into a talented screenwriter.”

But as we stroll along the St Kilda foreshore, Harper’s wild auburn curls tossing about in the wind, her mind is not on movie-making. She’s three months into the planning of her fourth novel and I can sense her focus already swinging back to that hermetic writer’s room. “For me, the books have always been enough,” she says. “This is the most incredible job and I just want to produce the best books I can. If you write good books that you’re proud of, everything else takes care of itself.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout