James Reyne’s ‘terrifying’ career crisis

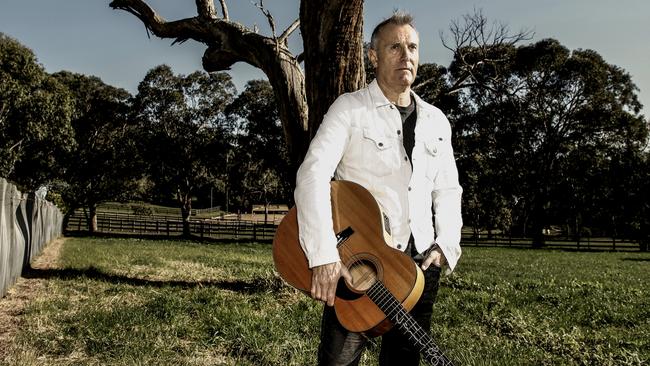

Former Australian Crawl frontman James Reyne reveals the terrifying health scare that left him unable to sing.

The alarm bells began ringing faintly at first, but their volume increased as it became apparent that the problem lay not with the muscles in his throat but with the instrument between James Reyne’s ears. Shakespeare had it right all those years ago: there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so. As Reyne found during a hellish few months, thinking he had lost his voice for good led the singer to convince himself he had.

His confidence plummeted and his performance anxiety peaked as the former Australian Crawl frontman found himself, at the age of 59, experiencing something new and unpleasant. He calls it “the yips”, a psychological issue usually associated with sports stars who suddenly find themselves unable to perform a skill that should be second nature: a golfer unable to putt, say, or a bowler who can’t release the ball. “There was a period of time, about three months, where I couldn’t sing, and it really freaked me out,” Reyne says. “When my voice came back, I just didn’t have the confidence. I was going out there thinking, ‘Oh my god, oh my god, is it going to work?’ I had this whole other psychological thing I had to get over.”

This all came about after a stroboscopy showed that something didn’t look right with Reyne’s vocal cords. For a guy who has made a living using his voice for four decades, this was no small matter. The idea was to zap the offending mass during surgery lest it turn into something more sinister. The operation in December 2017 was routine, but the outcome was not, thanks in part to Reyne’s unusually large jaw. “Apparently I’ve got a lot of bone mass in my jaw, and when I was under, they had to stretch my neck to get down to where it was – and my neck muscle spasmed,” says the singer-songwriter, now 63. “It was supposed to be a really simple operation... they zapped [the mass] and got it, no problem. But because my muscle had contracted it was pressing on my neck, so I couldn’t produce a sound.”

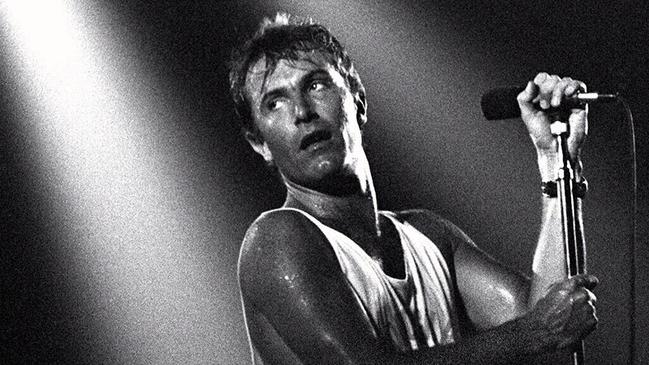

Worse still, this all took place in summer, when many performers make hay while the sun shines by playing as many festivals and headline shows as they can. Behind the scenes, the singer was in bad shape. “It’s terrifying, because performing comes to define you, especially after you’ve done it for so long,” Reyne says. “It’s your job, it’s how you earn your living – it’s everything. It played havoc with me for a little while. I thought, ‘What am I going to do? Who am I?’ Psychologically, you can’t express – and when you’re so used to expressing yourself in that way, it really toys with your psyche. I was really worried, and I lost a lot of work. I did a lot of talking myself down; I wasn’t going to do anything crazy to myself, but you get pretty depressed about it.”

During those fraught few months, Reyne ramped up visits to speech pathologist Dr Debbie Phyland, who he first saw in 2004 on the recommendation of fellow singer Vika Bull. “It’s a really, really scary thing for a performer to be so vulnerable and worried about their voice, and James is no exception,” says Phyland, who works at the Melbourne Voice Analysis Centre. Once it became apparent that the problem wasn’t going to resolve itself through vocal rest and exercises, she and her team scheduled surgery for Reyne, which would put him out of action for at least a month.

The nature of Reyne’s large jaw didn’t help matters while under the knife, and the difficult access to his larynx led to significant nerve pain afterwards. “It was probably one of the most difficult post-ops we’ve had for a while,” Phyland says. “James was already extremely worried about his voice, so the head stuff became the main issue to try to sort out and the voice stuff became secondary.”

Reyne’s return to performance was carefully managed. Phyland attended a show at Crown Melbourne, as she wanted to be there for him as a professional pair of ears through his vocal warm-up, as well as a gentle pair of hands to massage his neck muscles backstage before the show. “You’re literally riding their voice with them, every peak and trough. I was stressed, and I was crying with him, because I was totally involved.”

As far as just about anyone else in the audience that night could tell, there was nothing wrong with Reyne at all. He sang as he always had: with power, authority and confidence. He was so ready, in fact, that after the show he and Phyland soon parted ways. That’s the nature of her work with many performers: once she’s helped them overcome their particular challenge, whether physiological or psychological, they need to go away and do their thing without feeling the need to consult a professional at every turn. Who feels the need to see a doctor when they’re feeling well?

“I’m really glad he’s telling his story,” Phyland says of the man whose face graced posters in her bedroom as a teenager. “Because I think it’ll be incredibly valuable for other people who may not be as confident, because they can then see that someone like him can have that problem, and it doesn’t mean their vulnerability is a sign that they are not a great performer.”

Very few great performers are born that way; most require plenty of middling nights playing to small audiences before they figure out what works on stage. Reyne’s path to stardom began in his bedroom fiddling with ideas as they struck him, pairing them with some guitar chords then adding flesh to those bones with help from his friends.

Born in Lagos, Nigeria, where his British-born father worked for BP, James was two when the family moved to Australia. They settled in Mount Eliza on the Mornington Peninsula, where his mother was a high school teacher with a penchant for using her soprano vocals in local stage productions. “Our father was a relatively dark presence in our lives, but he lightened up a bit at night-time after a few… well, many drinks,” says younger brother David, 61. “And if you got him waxing lyrical, he was an interesting man. I guess he instilled in us the joy of books and the written word, and certainly music. We used to sit around the dinner table listening to jazz records, or [British comedy duo] Flanders and Swann, or those great British radio shows like My Word! and My Music. I think that definitely coloured James’s musical career.”

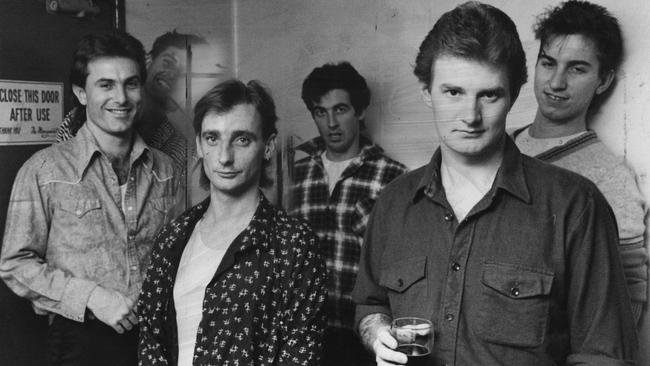

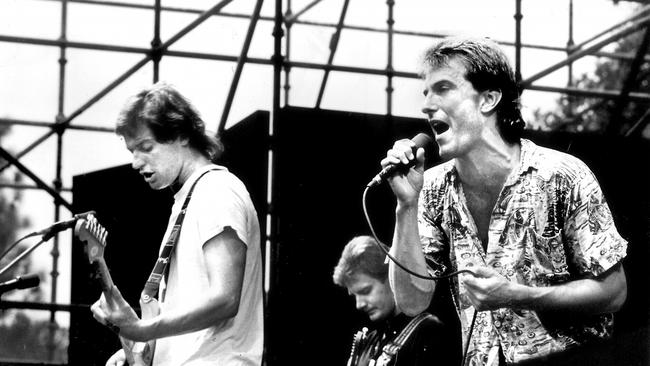

With four mates – including David, who initially occupied the drummer’s seat – James formed Australian Crawl, named after a swimming style. Some of his early songs were sketched directly from his observations of the landscape and the people around him. In time, as the band’s popularity exploded, it led to some social awkwardness for the frontman’s mother. “Occasionally he’d write songs that were very close to home, and particularly about the area in which we lived,” laughs David. “There were references to some people that my mother would try to avoid in the street.”

On the Mornington Peninsula, there was no shortage of attention from fans and fellow surfers as word began to spread ahead of the release of their debut album, The Boys Light Up, in 1980. “He was a giant, really, as the frontman of the hottest band going around in my circles, certainly in Victoria and on the Peninsula,” recalls broadcaster and journalist Tracee Hutchison. “They were considered godlike, but there was a sense, too, that they were ours. They were part of our tribe, and it was a bonus that everyone had caught on to the fact that they were great.”

As the band’s star ascended, Reyne’s head stayed the same size. “He always had a real ease around people; he always seemed to be central to the gang that he was with,” says David. “I’ve never considered him arrogant or egotistical, which is interesting because most people outside of his circle probably think that he is. He had a reputation for being a bit difficult and arrogant, but people who knew him never saw him like that.”

Reyne’s chiselled looks – including that jawline – featured on the cover of the band’s second album, Sirocco, which spent six weeks at No. 1 in 1981. Although he’d studied acting half-heartedly at the Victorian College of the Arts, he had no acting experience – yet he was cast in the hit 1983 TV miniseries Return to Eden, in which he played Greg Marsden, a scheming tennis professional who feeds his rich wife to a crocodile so he can inherit her wealth and marry her best friend. Return to Eden took three months to film, and his bandmates grew impatient. Asked to pick one or the other, he stuck with his original love of music, yet the band was not long for this world: following the release of a poorly received fifth album in 1985, they called it quits after a final tour in 1986.

The second act of Reyne’s musical career began in 1987 with a successful self-titled solo debut album, and since then he has never really left the stage or public life: for decades now, he has given as much of himself to his fans as fellow frequent flyers from that era of Australian music such as Daryl Braithwaite, Jimmy Barnes and Mark Seymour. But he keeps it on the stage. After a performance, it has long been Reyne’s strong preference to leave the venue immediately; some of those who know him well like to joke that he makes sure the car’s engine is running during the encore so that he can make a clean getaway. “He’s always been like that; not a loner, but he’s somebody who would really prefer to be in his close circle, or within the confines of his bedroom with a good book,” says David. “He reads several books on the go: ask him what heaven would look like to him, it would probably be a comfortable bed and a shitload of good books.”

As he has moved through his life, Reyne has regularly returned to a particular thought that has become a motif; a catchy chorus refrain that worms its way into his mind during moments both grand and mundane. Like that time when he was living in London, post-Crawl, and he wandered down to a large protest taking place outside the French Embassy. A crowd had gathered to demonstrate against France’s testing of nuclear bombs in the South Pacific, and for a while, Reyne was just another face in the crowd, taking it all in – until an Australian spotted him and announced his presence on the microphone.

Suddenly, a bunch of fellow expats were urging him to get up and sing his most famous song, supposing that it might be construed as an anti-war song because of that line in the chorus: Throw down your guns / Don’t be so reckless. It’s not, but a busker handed him a guitar and Reyne belted it out all the same; the crowd gave a big cheer then returned to chanting peaceful slogans. The momentary headliner, meanwhile, handed the guitar back and headed home, buzzed, but thinking: What the f..k was that? If I hadn’t written these funny little songs in my bedroom, shit like that wouldn’t have happened.

It’s a cross between gratitude and incredulity, that little motif, and it has hit him while visiting pretty much every corner of Australia as a touring musician, including riding through the vast interior on the back of a truck to play pop-up festivals in the middle of the desert. Same deal when visiting China as a guest fundraiser for the Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness & Research Centre alongside Cliff Richard and Joan Rivers in 2008 and being shown parts of the Great Wall that tourists couldn’t ordinarily access. And when striding through New York City for some recording commitments, he again heard the refrain whispered in his ear: If I hadn’t written a couple of silly little songs in my bedroom when I was 18, I wouldn’t be walking down Fifth Avenue right now.

Although the dimensions and surroundings of his various bedrooms might have changed considerably across those 45 years, that’s where Reyne still prefers to write. In the 21 years since he returned to living on the Mornington Peninsula, his favourite creative space has always been a desk in the corner that looks out onto a paddock, with a piano and a couple of guitars close at hand. It’s where he composed the 10 songs for his upcoming 12th album, Toon Town Lullaby. After some morning exercise, he’d follow the discipline of planting his arse in a chair and devoting himself to following ideas to their endpoint, and if his thought process was interrupted mid-flow by an intruder in his bedroom, he might react sharply before making a joke about the nature of how he earns his livelihood. See this ceiling? he’d say, pointing skyward. See that paddock? Sweating over songwriting earned me this view.

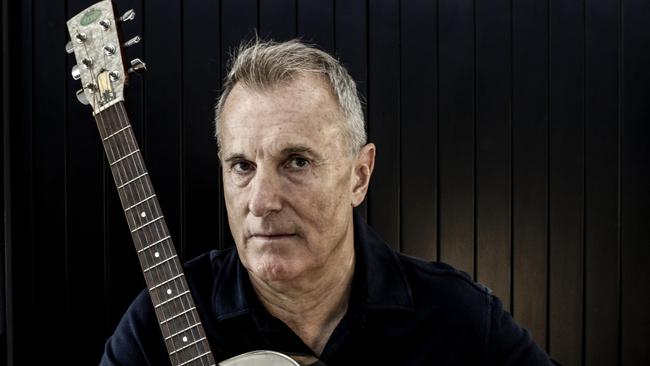

His favourite acoustic guitar belonged to Brad Robinson, his late friend and bandmate in Australian Crawl. He feels that guitars should be played rather than gather dust, which is why he bought it from Robinson’s family. The Martin instrument was his friend’s pride and joy, and now it is his. For years, he never changed the strings and they never broke; now, he changes them a few times each year, but that guitar never leaves his house. It rarely leaves this room, and it’s one of very few objects to which Reyne attaches sentimental value.

With that guitar, he wrote a song about Robinson that appears near the end of Toon Town Lullaby. Named The Tallest Man I Ever Knew, it’s a mid-tempo rocker shot through with a trebley lead guitar riff that comes across as a touching tribute without veering into mawkishness. Within four and a half minutes, Reyne manages to fit in a bunch of in-jokes he shared with Robinson, including an obtuse literary reference to a Nabokov poem the pair used to puzzle over. In its third verse, he captures his friend thus: There were twenty thousand flutterin’ hearts broken night and day / He didn’t care where he was going, but he was on his way.

It was a tough year, 1996: Reyne’s father died of cancer, aged 69, then three months later, lymphoma claimed Robinson’s life at 38. He and Reyne had been friends since they met at school at the age of eight, then all the way through Australian Crawl, from nobodies to local somebodies to national rock stars and out the other side. Robinson accepted the finality of his disease and retained his sense of humour despite his situation; near the end, Reyne recalls visiting his mate and being offered a cheeky swig of liquid morphine from the bottle by his bedside table.

Plenty has changed in Reyne’s life since the pair parted ways 24 years ago: his first child, Jaime Robbie, is now 35 and pursuing a career as a singer-songwriter, while his second child, Molly, is 21 and at uni. In 2017 Reyne tied the knot for the first time, marrying his long-time friend Leanne Woolrich; David Reyne summarises that relationship as only a younger brother could: “They’d always got on like a house on fire, and she was Kylie Minogue’s personal assistant for 20 years or something, which pleased me no end, because I thought, ‘Oh, well, she’s used to divas – so that’s a good starting point!’” he says with a laugh. “But she’s just fabulous: she understands him, and she gets the business. That can be really, really challenging for the partner of somebody in the public eye.”

None of it would have happened, though, if a teenage Reyne hadn’t backed himself to start writing songs all those years ago. Like many artists with decades of skin in the game, he feels his best work is in the present and future rather than the past, but he has learnt from experience not to get his hopes up too high on the eve of a new release.

“I still write songs just because I like doing it, and I’m quite realistic about the fact that the general public are not going to be bombarded with this record,” he says of Toon Town Lullaby. “They’re not going to be fully aware of everything like they would’ve been with the first few Australian Crawl records, and my first few solo records. I figure this is going to have a relatively low profile. It might not; stranger things have happened. But I’ve always written songs pretty much just for my own satisfaction.”

That’s what he did yesterday, and it’s what he’ll do tomorrow, in the full knowledge that some of these songs might never be performed live, while only a fraction of the millions of Australians alive today who know his name and his hits will be paying close enough attention to know – or care – that he continues to publish new work.

But that doesn’t bother Reyne, because the act of writing, recording and releasing music has long since become akin to an artistic tip of the hat to the craft that gave him his life and his place in this world. With a guitar in his hands that once belonged to his dead friend, he’ll work the fretboard and use his voice in search of new combinations of words, melody and harmony. Some days, the search itself is its own reward.

Toon Town Lullaby is released on July 10.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout