It’s the holy grail of productions – can Cats bounce back from film failure?

As it opens on its 40th anniversary tour, we learn the secret to reviving the beloved stage musical.

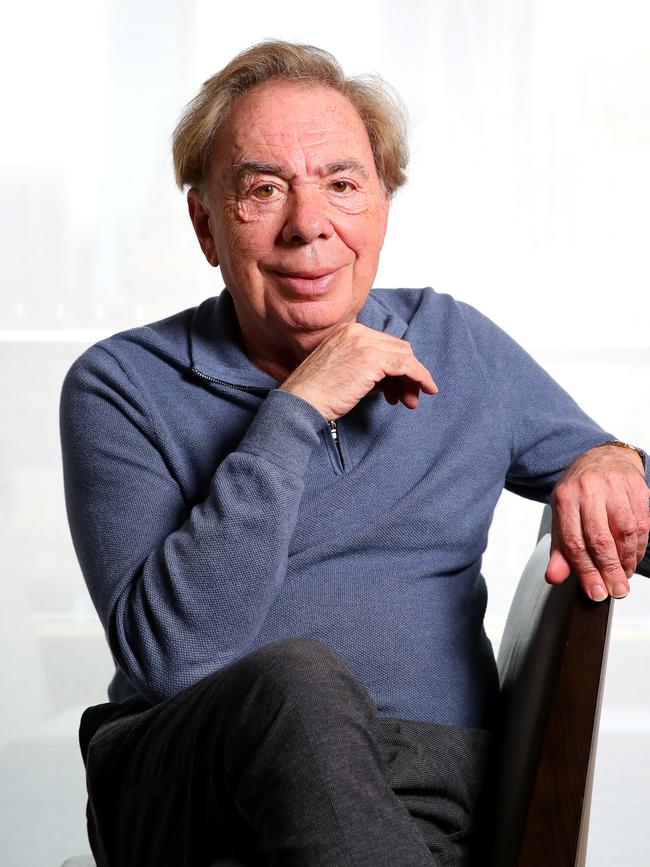

“There are several ways in which this might be a failure,” T.S. Eliot wrote of his strange little book of cat poems, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. If Andrew Lloyd Webber didn’t necessarily utter those same words 40 years later when he came up with the idea to turn Eliot’s whimsical poems into a musical, plenty of other people would.

Writing in his memoir, Unmasked, Lloyd Webber says his idea for Cats – which has to date earned approximately $3.57 billion worldwide, making it one of the highest-grossing musicals of all time – was “spurned by theatrical investors as madness” and “scoffed at by critics”. It’s not hard to see why: the show had no plot, all the characters were cats, and the score was a hallucinogenic ride of Moog-synthesised pop via opera, jazz, music hall and rock. It proved well-nigh impossible to find backers and Lloyd Webber would end up taking out a second mortgage to finance what he had come to describe as his “suicidally stupid musical”.

But when Cats premiered at the New London Theatre on May 11, 1981, it defied every expectation of what a successful musical could be. The Sunday Times declared it to be “among the most exhilarating and innovative musicals ever staged”. The Guardian described it as “an exhilarating piece of total theatre,” with “dazzling staging” by director Trevor Nunn and “brilliant choreography” by Gillian Lynne. By opening weekend the theatre was filled with patrons leaping to their feet to deliver three-minute standing ovations. The show would run at the theatre for almost 9,000 performances, and win the Olivier Award for Best Musical.

It stayed in the West End for a record-breaking 21 years and was a raging success across the pond, running for 18 years on Broadway. A Japanese production at the Shiki Theatre has been running for 41 years, making it one of the longest-running theatre shows in history. The show has been translated into 23 languages and seen by over 81 million people worldwide. Despite the initial doubts and financial risks, Lloyd Webber’s spectacle about one night in the life of a clowder of cat-people singing poetry, gyrating in unitards, crazy wigs and painted faces tapped into the zeitgeist and quickly became a theatrical juggernaut. How?

“It’s a complete piece of theatre,” says Chrissie Cartwright, who has worked as associate director and choreographer on productions of Cats since 1986. Cartwright is on video call from her home in the UK and getting ready to travel to Sydney to oversee rehearsals of the 40th Anniversary Australian tour of the show, which begins its run at Sydney’s Theatre Royal in June. “It has beauty. It has compassion. And that central story of someone who’s fallen on hard times is something we can all identify with. As long as we tell that story in a compassionate way it has something for everyone. We make sure it’s child-friendly. Even people who might be dragged along to see it reluctantly can’t fail to clap along to Mr Mistoffelees. I think it draws everyone in.”

As for the plot (which unfolds in defiance of musical convention, with no love story), it’s one night in the lives of a quorum of cats who gather for the annual moment when their guru, Old Deuteronomy, announces which cat will transcend to the “Heaviside Layer” afterlife. Will it be Rum Tum Tugger with his eroticised Jagger-esque swagger? Or the bedazzled Mr Mistoffelees? Could it be Grizabella, the former Glamour Cat whose life of excess has left her ravaged and vulnerable, stalking the stage wide-eyed in a tattered coat? Old Deuteronomy listens patiently to each cat’s story, before one of them, after belting out the show’s musical altarpiece Memory, ascends to heaven.

“It’s all of the forces coming together,” Cartwright says. “It’s visually beautiful. The set and costumes and makeup are brilliant. And all of those original creatives, who were absolutely at the top of their game, being together… It just works to bring all those incongruous elements into one piece.”

Except when it doesn’t.

It’s a Tuesday morning in Sydney’s Waterloo as a bunch of young performers in leotards and leg warmers end a gruelling round of rehearsals and take a break. Before they can get to their water bottles, two actors spill out of the back room with full faces of makeup. They’re the first cast members to have been transformed into their characters, and are set upon by their co-stars who paw them and coo with delight.

“You can never have too much powder,” says Kellie Ritchie, head of wigs and makeup for the production. “It’s a very sweaty show.”

Ritchie has spent the morning teaching two of the performers how to apply their own makeup – first applying flat layers of colour and blending, then the individual markings that bring out each cat’s distinct character. The marks need to line up with the details in the character’s wigs, which are designed to blend into the makeup and are hand-knotted into each performer’s hair before every show.

Leigh Archer, who has been cast as Jennyanydots, is about to have her first crack at copying Ritchie’s work. The makeup artist has finished one half of Archer’s face and is encouraging her to finish the rest. “Press the brush flat at the hairline and then turn it as you get closer into your face,” she says. It’s harder than it looks.

Jarrod Draper, who plays Munkustrap, the show’s narrator, has had one side of his face done and is now standing up close to the mirror trying to get his brushstrokes right on the other side. “It’s going to be like a top-tier designer on one side and then the Temu version on the other,” he says, laughing.

“When you first put the makeup on you actually have to look really hard to see the person’s face,” Archer adds. “But then after a while, you see the person’s face straight away.”

Draper describes the process of being made up as “like putting on a suit of armour ... it’s a fully transformative experience”, he says.

The 22 cast members will all learn to apply their own makeup, and will do so eight times a week. “They call them triple threats,” Ritchie tells me. “But they have to be makeup artists too, so we call them quadruple threats.” She says that, among makeup artists, Cats is seen as the “holy grail” of productions.

Theatre designer John Napier’s creative vision is often described as key to the show’s success. The original set (inspired by Eliot’s poem The Waste Land) was a surreal landscape, an oversized junkyard filled with tires, pipes and old boots. He dressed the performers in body-hugging unitards that allowed them to move with balletic fluidity (Lynne’s choreography – fusing classical ballet, modern dance, jazz and animal movements – is considered to be among the most challenging in musical theatre) and designed wigs and makeup to shapeshift them into cat-human hybrids.

“John’s design was to identify both the cat and the human in each character,” says Cartwright, who worked alongside Napier, Lynne and many of the original creators. “He didn’t want it to look like face masks that would hide the person playing it. And it’s the same with the whole costume. It’s so important that the cats keep their humanity.”

And yet it was the cats’ complicated relationship to humanity that led to the catastrophic flop of Tom Hooper’s 2019 film adaptation starring Judi Dench, Rebel Wilson, Jennifer Hudson, Ian McKellen and Idris Elba. The film was a total failure, not just critically but financially too – its budget was reported to be $95 million and it made $75.6 million worldwide.

Arguably, it all went wrong when the film decided to eschew Napier’s original designs and digitally graft feline features, tails, and fur onto the actors’ bodies. The moment the words “CGI digital fur technology” reached the internet, the film seemed predetermined to become the biggest Hollywood bomb since Waterworld. When the trailer dropped in the months leading up to its Christmas release, the world watched aghast as a strangely catified version of Judi Dench lifted a leg and licked her nether regions. (Nobody wants to see Dame Judi like that, I recall someone writing beneath the trailer on YouTube).

Writing in The New Yorker, critic Anthony Lane posed a series of questions: “Few of us go to work in suits made of human skin, so why would a cat, even a cold cat, wear a fur coat that appears to have been fashioned from more cat?

“How to respond to such a spectacle? Will you be amazed, bemused, allergic, or agog? Many people, I suspect, will lean forward in their seats, peer at the peculiar creatures that romp around onscreen, and ask, ‘What in God’s creation are they? If they’re talking cats, why do they have normal hands? If they’re men and women, how come they fit through a cat flap?’”

Speaking to Variety, Lloyd Webber remarked: “I saw it and I just thought, ‘Oh God, no.’ It was the first time in my 70-odd years on this planet that I went out and bought a dog.”

So does a show as weird as Cats only work when you don’t mess with the original formula – wigs, makeup, unitards and all? Perhaps. Rehearsals in Sydney will continue under the seasoned eye of Cartwright, who understands exactly what makes Cats work and what does not. “I saw the film in a little cinema in my village, on my own,” she tells me. “I was going to resist it but there are some wonderful people – friends of mine – in the film, and, of course, they were all brilliant. I think, with Cats… it’s a fine line. I’ve seen productions where I’ve thought, ‘They’ve missed it tonight’. And it’s to do with the belief in the animal, that you are that animal. If you stray from that, then you’re just playing at something. I remember Andrew Lloyd Webber talking to a company and saying, ‘We have to believe that you really are cats.’ There are lots of people who can sing and dance it, but there aren’t lots of people who can really believe in it ... that’s the joy of Gilly’s choreography, it never strays from the shape of a cat, if we get it right.”

Cartwright speaks reverently about the choreography of Lynne, who died in 2018. “If you look at a cat, it is very elegant, very neat, but then it will suddenly turn into something feral. And, that’s what Gilly managed to capture. There are very sensual moments and then there are rather savage moments. It flicks from sensuality to savagery constantly.”

John Napier’s show “bible”, created during the pandemic, will ensure future productions don’t go off the rails – a template of sorts, Cartwright says. “While ‘template’ might sound inartistic, the choreography is the choreography and it stands the test of time. And the story is the story.” It’s a story, she notes, that includes characters like Gus the theatre cat (His name as I ought to have told you before / Is really Asparagus, but that’s such a fuss), based on a 1939 poem infused with longing. “That’s a story about life.” says Cartwright. “It’s a story about the elderly and how, if we bother to listen to them and listen to the stories of many generations, we learn, and we become better people.

“There’s nothing out of date about this topic. It’s a very current subject matter. It’s about redemption, and in this world that’s vital. It’s about learning to forgive, learning to accept, learning to tolerate differences and finding out how to redeem.” b

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout