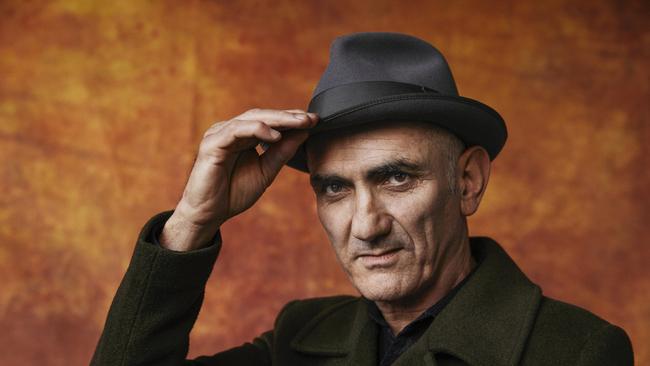

‘It’s like a friend’: Paul Kelly on his favourite poems

For songwriter Paul Kelly, it all started with Shakespeare. Now he wants to share his lifelong love of poetry.

Many people I know say they feel poetry is difficult. That it seems “worthwhile” but that “worthiness” puts them off. Fair enough. But poetry is friendlier than they think. It hovers close by us. It’s in pop songs everywhere we shop, work and play. We often reach for it on ritual occasions. Poems are read or quoted at funerals, at weddings, at ceremonies. And good speechmakers – Barack Obama, Noel Pearson, the mother of the bride at my friend’s wedding earlier this year – all consciously and subconsciously adopt poetry’s techniques of rhythm, repetition, rhetoric, assonance and cadence.

It lives in our everyday speech, though we may be unaware of it. The common phrases “without rhyme or reason”, “vanished into thin air”, “played fast and loose”, “tongue-tied”, “short shrift”, “cold comfort”, “good riddance”, “high time”, “foul play”, “the long and short of it”, “it’s neither here nor there”, and a host of others, all sprang from the plays of Shakespeare which, for the most part, were written in 10-syllable lines of verse.

Shakespeare was where it started for me. We did Macbeth at high school and I was hooked. When Lady Macbeth said, “Come, you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here,” the hairs rose all over my skin. His language always gives me a jolt. I still have a physical reaction to Shakespeare even when it’s done badly.

At school we also studied Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale and it gave me the same kind of thrill. It’s the first poem I ever consciously memorised and it has stayed with me ever since.

The language of Keats and Shakespeare, highly charged and deeply playful, can sound over-rich to modern ears. Many contemporary poets work in an elevated register, too. But not all. Ko Un’s Morning Birdsong has only one line:

I didn’t die – waking up I hear that.

As plain as can be. And poetry to me.

So where to start with poetry if you want to read it but are overwhelmed by the myriad paths before you? If you were put off by the way you were taught at school? My own experience may be encouraging. I discovered W. H. Auden and E. E. Cummings (he of the lower case) through movies. John Hannah reciting Auden’s Stop all the Clocks (Funeral Blues) in Four Weddings and a Funeral; Cameron Diaz reading Cummings’ I Carry Your Heart With Me in In Her Shoes. But when I went and followed these poets up I found that most of their poems were opaque. I didn’t get them. Only a small fraction knocked my socks off. That small fraction, though, can add up to quite a lot. This happens with most of the poets and poems I read. The strike rate per poet is low. Yet, when I’m asked now who my favourite poets are, Auden – most of whose work is unintelligible to me – is one of the first names on my list.

So let yourself off the hook when you’re reading a poet someone’s recommended, or following a lead gleaned from an article, book, movie, song or any other source. Many poems are obscure, full of insider information and private symbolism. Finding a poem you love requires patience, luck and a willingness to cover a wide range.

Anthologies can be helpful. I looked at many of them while hunting poems for my collection of favourites, which I hope, in turn, will send you hunting. Three in particular led me down rich byways: The Rattle Bag, edited by Seamus Heaney and Ted Hughes; 60 Classic Australian Poems, with commentaries by Geoff Page; and A Book of Luminous Things, compiled by Czeslaw Milosz.

Like Ted and Seamus did in The Rattle Bag, for my anthology I have arranged the poems in alphabetical order by title or first line. Undeniably, I have a thing for the alphabet. Within its unshiftable structure, randomness is given full rein. Grouping the poems alphabetically by author would make the book too blocky. By theme, too textbooky. The best poems straddle multiple themes, anyway. And ordering the poems chronologically would seem too much like an incomplete history lesson. Listing the poems alphabetically by title allows them to jostle one another in a democratic manner – the transcendent with the earthy, the loquacious with the sparse, the hymnic with the polemic. In one sequence under H, for example, Sylvia Plath, Sappho, Thomas Hardy, Warsan Shire, Emily Dickinson and Tusiata Avia all get to hang out together and have sparky conversations.

As that short list shows, I have felt free, fortified by the sturdy alphabet, to roam far and wide across centuries and countries to gather my poems. Homer and the Greek tragedians speak to us from thousands of years ago. The 3000-year-old or more Song of Solomon, first written in Hebrew, translated into Greek, then Latin, then into English via the King James Bible, rubs shoulders with Walt Whitman and Yehuda Amichai, giants of the 19th and 20th centuries, both of whom, as it happens, drew heavily on the Bible for their own work.

There are many very well-known poems in my book. Some are so popular that their inclusion may seem banal. But my simple rule was if I love a poem, it goes in, no matter how worn out others may think it to be. You can’t wear out a good poem, anyway. Sometimes at our big family Christmases or get-togethers we have a kind of talent night where everyone chooses to perform an item – a song, a poem, a trick, a joke or a dance. Rudyard Kipling’s If, one of the most popular English poems ever, was memorably recited by my English nephew one Christmas and Banjo Paterson’s The Man From Ironbark is my brother John’s go-to performance each year, complete with acted dialogue and throat-cutting gestures.

I did have another rule. Not to include song lyrics. I know many could be claimed as a form of poetry. The Kinks’ Waterloo Sunset, The Triffids’ Wide Open Road, Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come and Joni Mitchell’s River jump straight to mind. A lot of rap and hip-hop, too. For most of human history poetry has been sung. Homer was. And much of the Greek tragedies. Many songs were poems before they were songs; Danny Boy is a famous example. But including songs would have opened up a huge other well, one I wasn’t prepared to dive down.

However, when you make the rules you’re allowed a few exceptions, so I included Took the Children Away by Archie Roach, one of the most important Australian songs of the 20th century. And Kev Carmody’s I’ve Been Moved, a song which, like many of his, was written as a poem first. Danny Boy gets a pass, too. And I’ve thrown in the old folk song Katie Cruel, for these lines which describe more succinctly than any other words I know the hunger of being human, the longing for love, earthly or divine:

If I was where I would be

Then I’d be where I am not

Here I am where I must be

Where I would be, I can not

Another notable exception is a piece of prose – the Uluru Statement from the Heart. It has the heart, hurt and urgency of great poetry.

I’ve been fortunate, over the years, to have had friends and family send me poems in letters and emails or books in the mail. Fifteen years ago my cousin Fiona gave me for my birthday a book of poems by a Polish poet with a name I couldn’t pronounce. Wislawa Szymborska. It languished in my pile of books by the bed for almost a year. Then one day I opened it again and fell in love.

The stunning The Statue of the Virgin at Granard Speaks by Paula Meehan landed in my inbox like a bomb from my friend Martin and soon led me down dark and beautiful paths of Irish women’s poetry. My friend Grant, now hid in death’s dateless night, once sent me a postcard from America with a few scribbled lines from John Berryman’s The Ball Poem. Those lines gave me a song. And 40 years ago in a Paddington bookshop the poet Robert Gray, a friend of my cousin (another cousin), gave me a book of Thomas Hardy poems. Until then I’d only known him as a novelist. When I opened it I saw Robert’s favourites lightly marked with pencil. I started with those poems, and so began my long march with Tom. I still have the book. Thank you, Robert.

Poems are to be passed on. They’re pocketable, transferable. Little mind bombs. Wherever you are, on the tram or stuck in a queue or waiting on a friend, they’re fun to commit to memory. That’s what poetry has been ever since Homer. Something to memorise. The great poets have the knack of writing unforgettable lines:

I put your body

between me

and the history of horrors

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways

When you do nice things to me

all heavy industry shuts down

Poetry is deep play. It’s comfort. It’s challenge. Just like a friend. To be approached any time, any way. Day or night. In a light mood or dark.

I’ve never formally studied poetry. I’m an amateur following my nose, with huge gaps in my knowledge and a wide streak of bias in my choices. By the time my book is published I’ll be kicking myself for the poems I’ve left out. The poems I’ve missed. Please pick them up for me. Pick them up and pass them on.

And let poetry be your friend. It can take you to the end.

Extract from Love Is Strong as Death: Poems chosen by Paul Kelly (Hamish Hamilton, $39.99), out Tuesday

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout