‘Is your father your abuser?’ Breaking free of the shame of decades of sexual abuse

Beck Rogers’ case, according to experienced police officers, is the worst case of incest they have encountered. While sharing it with us, her health suffered. And yet she is resolute in the hope that her story will reach someone who is suffering in silence.

The first step across the threshold of a police station is the hardest one to take for sexual assault victims. In April 2023, Beck Rogers trembled as she entered the Sexual Offences and Child Abuse Investigation Team (SOCIT) office at Frankston in Melbourne’s southeast. Her husband, Will, had done the research. Don’t go to a police station, he told her. A Google search urged victims of sexual abuse to go directly to one of the 28 SOCIT offices in Victoria.

Beck felt a wave of nausea and her head pounded, but she pushed on. She was ushered into an interview room. Her mind raced. Where to start? How to unravel 36 years of sustained torture? Beck had suffered a lifetime of protracted sexual abuse, emotional control and financial coercion committed wilfully and frequently by her father.

In telling this story to The Australian Weekend Magazine, Beck Rogers has decided not to hide behind an alias. She is now 41, a wife and a mother. Not long ago, it would have been almost impossible to share her experience publicly in this way. She would have been tied up in suppression orders that ancient lawmakers had deemed were put in place for her own protection.

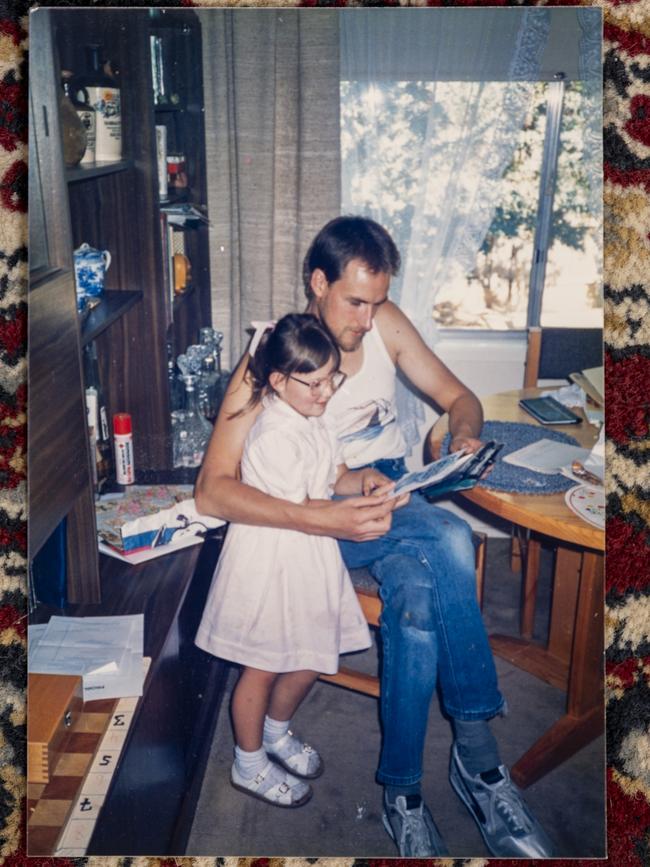

Beck’s first memory of life was sitting in the bath at her Frankston home. She was three years of age and her father had touched her indecently. The last episode of sexual abuse would take place over three decades later.

A male detective sitting across the table took notes as she spoke. Beck found him impassive and intimidating, if not downright scary as he initially played devil’s advocate, warning her that if her story was contrived or fabricated she could face criminal charges. A female social worker sat in, too, her kind eyes and gentle smile a merciful contrast to the detective’s stony face. Beck pressed on and the detective’s tone would begin to soften. Beck could tell she was believed. She left the SOCIT office 45 minutes later, with a police business card and a promise that she would receive a call within days. A week later, she was summoned to the SOCIT office again. Detective Senior Constable Kathy Squire had been assigned to her case. Squire had read the notes taken at the preliminary interview and was aghast. She had been investigating sexual assaults for 30 years but had never seen anything quite like this.

As a professional, Squire kept her emotions in check. Her job delves into humanity at its worst. Maintaining distance between herself and victims was necessary. Yet she has a heart.

“I was immediately drawn to Beck,” Squire tells this Magazine. “Her smile was infectious but I knew it concealed horrific abuse.”

The two women bonded as Beck’s life was stripped bare. Beck’s statement was prepared during four separate sittings over two weeks. The first would take seven hours, the second the same, then six hours and finally two.

Outwardly Beck’s demeanour was determined and resolved, but she would find the process exhausting, triggering and re-traumatising. She had night terrors, shrieking herself to consciousness from intermittent sleep. Beck has suffered from seizures for much of her adult life. At first she was treated for epilepsy. Later, she was diagnosed with Functional Neurological Disorder, a trauma-related condition. The seizures became more frequent after she decided to confront her past, but she was determined to push on.

It had been a warm February evening in 2023 when Beck decided the abuse had to end. She and Will had arrived at her father’s home for dinner. Over pasta her father, Stephen Colwill, asked the couple if they would take out a mortgage on his home. He was struggling with the payments, he said, seemingly untroubled by the fact that Beck and Will were renting and saving for their own home. Beck suddenly saw what her father’s begging meant. The coercion would never end.

“It was like a gut punch. I felt sick in the pit of my stomach,” she says. She dashed to the toilet and was violently ill. It was the last straw on a long list of her father’s sins.

In the weeks that followed, Beck’s determination to end her father’s control over her amounted to prolonged suicidal ideation. She decided she would travel to her father’s home and slash her wrists in front of him. For days on end, she contemplated a terrible death and prepared her last words, a final corrosive spray, staring into her father’s eyes. “I would say, ‘Because of you, I don’t want to live anymore’.”

It may have ended that way had it not been for the intervention of another family member who was observing Beck’s distress. As the two women talked, Beck was tearful and reticent until she heard a question she could not shy away from: “Is your father your abuser?”

While the path was not yet obvious, Beck saw that there could be another way to end her pain. First, she had to tell her husband.

Will is a big man – 190cm tall on a frame tipping the scales at 110kg – and a former rifleman with the ADF. The couple met in 2001 and quickly grew close. They’ve been together now for 24 years. They married in 2015, 10 years after their son was born.

There is no good time to speak of the unspeakable, but Beck chose her moment after dinner and when her son had gone to bed. Visibly shaking, she started her speech mindful of the threats her father had so frequently impressed upon her.

For the first time her husband was enjoined in the darkest of secrets – and unsurprisingly, his first reaction was shock and anger. “I wish you had told me this 20 years ago,” Will told his wife, and stormed out into the backyard to smoke one cigarette after the other until he reached a state of calm. He went back into the house, kissed his wife and told her, “I’ll be there for you.” And he has. Every day.

The rate and frequency of incest or interfamilial child sexual abuse in Australia is not properly understood. There are obvious issues around reporting or the lack of it. Victims are more likely to be cajoled or threatened into silence.

Clare Leaney, co-founder of the National Survivors’ Day and CEO of In Good Faith Foundation, an independent recovery service for victims of child sexual abuse, says the act of coming forward requires extraordinary determination amid deep fears that the family unit will not survive the victim’s revelations. “Let’s not understate the courage it takes for victims to report the crimes committed upon them, knowing there will be ramifications that can lead to family breakdown. This can never be spoken of highly enough,” says Leaney. “It is too easy to sermonise and neatly fit child sex offenders into a stereotype. [But] it is far more likely that the abuser is a family member or a close associate.”

The Australian Bureau of Statistics published statistics on child sex offending in 2023 that showed 10 per cent of Australians have suffered sexual abuse at the hands of a family member, while just two per cent experienced abuse within an institutional setting.

As Beck’s story became known to police, many wondered how the abuse could have continued for so long into her adult life. Even Kathy Squire’s police colleagues, hardened by years of investigating sexual assault cases, were among them.

“The level of control a person asserts on their victim can in some cases become normalised to the victim, as it is all they have ever known,” Leaney explains.

Squire offers her own thoughts: “You have to remember the time period and how young Beck was when it began. The abuse and threats went hand in hand. Her father had frequently told Beck that if she decided to tell all, she would be responsible for the ensuing family breakdown. She came to believe she would wear the blame.

“When I first met Beck. I could tell how well he had groomed her. Beck knew her father’s depravity was wrong. But it was far easier to give into his demands. It was easier to give in than deal with his anger. Beck loved her father and craved a father’s love. She had hoped that the abuse would end and that a normal father-daughter relationship might somehow emerge.”

While acknowledging that she feared her father, Beck tells this Magazine: “I was more frightened of losing my family.”

Beck’s mother once walked into her daughter’s bedroom to find her husband in bed with her. Beck was 11 years old. Her youngest sister, Jess, was not quite six. Their mother immediately evicted Colwill from the family home. Colwill took up lodgings at his parents’ place in nearby Seaford, and remained there for 30 years.

Colwill insisted on access visits every fortnight – and on almost every occasion, Beck was sexually abused. The abuse became more brazen with Colwill enjoying the freedom of living with only his two elderly parents to watch over him. The penetrative sex had begun when Beck was just eight.

Despite earning a decent wage, Colwill was always broke. He’d splurge his pay cheque on clothes for himself, CDs, hi-fi equipment and his substantial pornography collection. There was little money at home for Beck and her sister, who often went without food.

At 14 Beck began working at a local ice cream shop, only to see her meagre wages taken from her to pay for the family’s food bill. Financial control was enjoined with sexual abuse. When Beck and her father met for a meal at restaurants years later, she would always pay. She bought him groceries when he complained of having no food. She paid his electricity bills after he moaned about being penniless.

Later, when Beck became pregnant with her son, her father suggested Will would leave her. Colwill often fantasised about a life with his daughter and the child they would raise as their own. Pack up and go live in the country somewhere, he thought.

The abuse and control continued, hidden in plain sight, until Beck knew that it could only end when she ended it.

With Beck’s 32-page statement, Detective Squire obtained a warrant to search Colwill’s home. Beck thinks her father had become complacent, certain that his daughter would never find the courage to go to the police. He had always told her, “If anything happens to me, get the hard drive out of my computer and run it over in your car. Destroy it.”

When police came calling on July 30, 2023, what they found was a smoking gun of corroboration, including sexualised images of Beck from a glamour shoot Colwill had arranged for his daughter. He was arrested immediately and charged with 60 offences.

Colwill denied everything. Remarkably, he was bailed the following day. Beck was left fearful of her father’s reprisals. Squire had filed orders with the courts restraining Colwill from making any contact with Beck or Will. Colwill, trying to paint himself as a victim, argued that he was the one at risk, inferring Will might turn to some rough justice. Not long after being bailed, police ordered Colwill to hand in his knife collection.

Beck fretted over giving evidence and the inevitable cross-examination, but on the eve of a committal hearing at the Melbourne Magistrates’ Court in May 2024, she received a call from a solicitor at the Office of Public Prosecutions. Her father had agreed to plead guilty to 30 charges. Beck felt no relief. “I was quite gutted,” she says. “I wanted to take him down. I felt I had been denied my chance to speak.”

By the time the plea hearing took place in the County Court in November, the plea deal had been rolled into just nine charges with a single count of rape removed. This infuriated Beck but she knew it was beyond her control. Colwill remained on bail.

As her father formally pleaded guilty, Beck took comfort in knowing he would be present in the courtroom when she delivered her victim impact statement. She had laboured for hours over it. Judge Patricia Riddell permitted Beck to make her statement seated with Will holding her hand. Her father sat in the dock, and she looked him in the eye.

“I have carried the weight of my situation and carried emotional baggage that I refuse to carry around any longer,” Beck said. “I am handing it over to you now, father. You get to feel the weight and have the burden of shame. You can be humiliated now. You can finally pay for what you have done. You have ruined the last 41 years of my life, inflicting unimaginable pain and suffering. I have no father. Exposing you is the beginning of my new life. I am going to not only survive, but I am going to live life and be truly happy surrounded by all the people that you tried to convince me would run away. I am not alone, but you will be. I will take my past and draw strength, resilience and make every moment count.

“I am finally free of shame, of embarrassment and of manipulation. But mostly, I am free of you and that is the greatest thing that I have ever achieved. So now, although I am seen as a victim in the court, in my heart, and in the eyes of all whom I care about, I am a survivor.”

Shortly afterwards, Colwill was taken into custody. He would face the court for sentencing in the new year.

On February 19, 2025, Beck entered the courthouse free of anxiety for the first time. Judge Riddell referred to Beck’s statement throughout her sentencing remarks. Beck looked at her father, who appeared by video link from prison looking gaunt and diminished, his power over her now gone. When the sentence came, Beck misheard or perhaps misunderstood it. She rose from her seat and left the courtroom thinking her father had been sentenced to 11 years. Outside there was applause and hugs. That’s when Beck heard it for the first time. Her father had been sentenced to 21 years and five months in prison, with a non-parole period of 14 years and eight months.

“I was in shock at first,” Beck says. “Then the penny dropped. ‘Wow, I have done it. I’ve got justice. I’ve got my freedom’.” But she wasn’t finished yet.

Victoria’s suppression laws – which silenced victims of sexual abuse – were amended in November 2020, with victims still able to choose if they wish to remain anonymous. Others who refuse to be silenced, like Beck, can have their say. And yet, public accounts of severe sexual abuse remain rare.

Says Squire: “These crimes often go unreported because normally the victim is told they will cause the breakdown of the family unit ... Shame, fear and guilt often prevent them from coming forward.”

Beck’s story, according to experienced police officers, is the worst case of incest they have encountered. While sharing it with The Australian Weekend Magazine, the frequency of her seizures increased. Beck cannot drive a car and is unable to work. And yet she is resolute in the hope her story will reach someone who is suffering in silence.

“I just want to help other people,” she says. “I often think if I had known about the stories of other people in similar situations, I would have come forward much earlier.”

Having the courage to go to the police put an end to her father’s abuse forever. Her story is one of survival – and telling it is an extraordinary act of generosity and a signal to victims that sharing their truth can set them free.

If you or someone you know is experiencing sexual abuse or family violence contact: National Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence Counselling Service 24-hour helpline 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732

Kids Helpline is for young people aged 5 to 25 on 1800 551 800

Don’t go it alone. Please reach out for help by contacting Lifeline on 13 11 14

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout