Inland Rail delivers boom times for regional towns

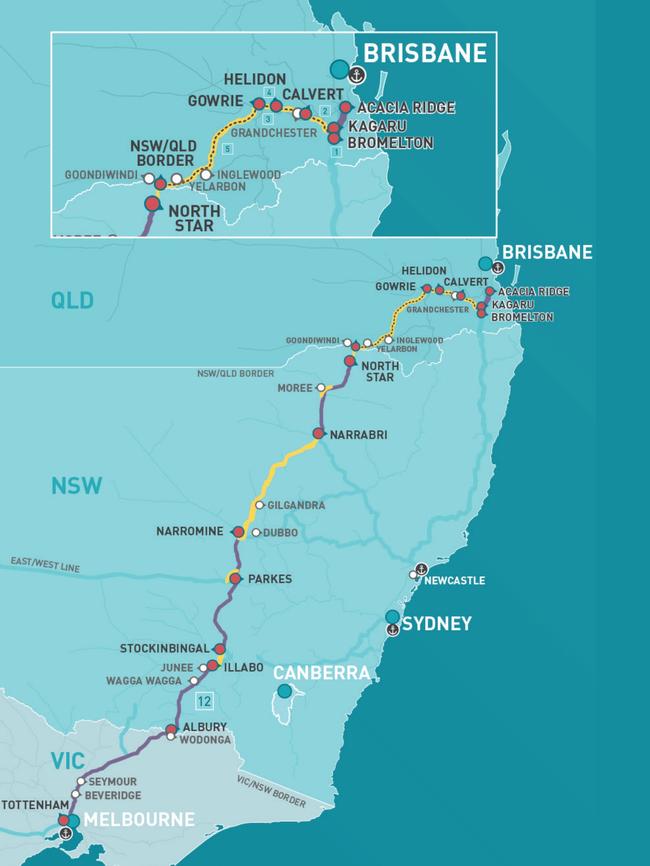

The $15 billion, 1700km Inland Rail project will revitalise dozens of communities in its path. But not everyone is on board.

For the past 99 years the Keith family has tended sheep and planted crops on the rolling hills of their property, Stanleigh, on the outskirts of Parkes in NSW’s Central West. Back in 1926 Kenneth Keith, the grandfather of Stanleigh’s current occupier, also Ken, felled cypress trees from the scrub and milled the timber to build a new home after the original homestead burnt to the ground. In the years since, the house has been tarted up and extended, but that timber still forms the bones of the home. “My wife and I have lived in the house for 37 years, the house that my grandfather built, ever since we were married,” says Ken Keith junior, now the mayor of Parkes. “It’s where we raised our three boys.”

Ken Keith is one of those people who have dedicated their lives to making their patch a better place to live. His pastime, his passion, his obsession is Parkes. He’s been mayor for the past 13 years. He’s been on the show committee for decades. He first stood for council in 1983, to be part of Parkes’ centenary celebrations. It’s more than likely he’ll be on a committee planning for the town’s 150th.

What Keith and the town’s civic leaders have long known is that the great hope for Parkes, population 12,000, is its location. It is on the train line that runs from Perth, past Adelaide and on to Sydney and Newcastle. The town is also on the train line that heads north from Melbourne. But this line does not cross the border into Queensland – it comes to a dead end at Boggabilla, a tantalising 9.7km from the border town of Goondiwindi and the entire Queensland rail network. It’s been like this since the line was first built back in the Great Depression. This missing link is the result of a deliberate, parochial decision to prevent wool produced in north-west NSW being exported out of Brisbane.

For years Keith has been travelling to conferences around the nation, pushing the case for the Inland Rail – the construction of a 1700km freight line that would link Melbourne and Brisbane via regional Victoria, NSW and Queensland. Parkes would become the great inland port – goods loaded on an afternoon in Parkes could arrive fresh on the doorstep of more than 80 per cent of Australia’s population by the next morning. It would become an obvious place for manufacturers, producers and distributors of all sorts to set up shop.

And then that grand dream started to become a reality. In 2017, after decades of promises and a host of studies, the Turnbull government allocated $8.4 billion to build the Inland Rail. Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce says it was a key part of the agreement he hammered out between the Liberals and Nationals after the 2016 election. “The Libs wanted Badgerys Creek [the second Sydney airport],” Joyce says. “And I insisted on the Inland Rail.”

Keith has been instrumental, too. About six years ago he and the shire’s general manager were showing a prospective abattoir developer around Parkes. In preparation for the coming of the Inland Rail, council had set aside 600ha on the edge of town to be used as a logistics hub and industrial park. The mayor soon realised that a development such as a large, modern abattoir, with an adjoining feedlot, would require a lot of space and a big buffer zone. The land they’d set aside was not big enough. It was then that the penny dropped – Stanleigh was next door. The reality was that if Parkes was to boom in the way Keith had envisaged, it would gobble up the farm that had been in his family for a century.

At that point he sought legal advice from a former ICAC commissioner and removed himself from all decision-making processes regarding the Inland Rail. He’s now allowed to talk about it because negotiations were recently finalised. Keith has just come through what he describes as a “pretty painful process” that resulted in his family farm being compulsorily acquired by the NSW Government under Just Terms legislation. “I am not entirely sure that ‘just’ is the correct term to use,” he says wryly. The government accountants had no regard for those hand-hewn cypress logs that had held up the family home for the past century. The “just terms” were just a cold, hard calculation on land value. “I can appreciate that selling my farm was a small sacrifice relative to the bigger picture,” he says.

On the day I visited, Keith was in the process of packing up 99 years of family history and moving to a house in town. “If the mayor wasn’t prepared to make a sacrifice for the benefit of the community, it would have been very hard for me to talk to others who will have to make similar sacrifices for the betterment of the town,” he says. Those conversations with his neighbours, including his brother, whose farm was also acquired, have been “fairly tough”.

Along with Stanleigh, four other farms have been bought by the state government to form the Parkes Special Activation Precinct (SAP), which will become a 4800ha industrial park. It’s enormous, the size of several large suburbs, and will dwarf the designated area for the proposed new Western Sydney international airport and business park, which is a mere 1780ha. Some estimates reckon Parkes’ population will grow by 1000 people a year for the next 20 years to reach 30,000 by 2040. Track work to upgrade the train line to the north, from Parkes to Narromine, was recently completed and 1800 people employed. “The Railway Hotel served something like 14,000 meals in three months,” the mayor says. It provided a huge cash injection to the town with more than $110 million paid out by Inland Rail to local businesses for their work on the project.

Similarly, it’s expected the Inland Rail will be a boon for other towns and cities along the route. While the Federal Government is spending billions building the rail line, the NSW Government is hoping to cash in with the industries it will create, building huge industrial parks in Wagga Wagga, Parkes, Narrabri and Moree, and incentivising businesses to relocate by offering building approvals in less than a month. As one wag quipped: “Almost as quick as Crown Casino.” The land will cost about a fifth of similar industrial land in Brisbane, Melbourne or Sydney.

The Federal Government’s investment of up to $14.5 billion will upgrade 1100km of track along the existing rail route and it will construct 600km of brand new track through fresh fields – filling in the missing links in the existing networks between Brisbane and Melbourne. When finished, the new line will have the capacity to handle double-stacked 1800m-long container trains that will travel at 115km/h. Each train will carry the equivalent of 110 B-double trucks, greatly relieving truck congestion on the inland road system, along with the impact on the environment. Some 21,500 workers will be employed on the project at peak periods before its planned completion in 2027.

The great dream of decentralisation – often talked about, rarely achieved – may finally happen. “This term ‘tree-change’, you can throw that out the window,” says NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro. He says the Inland Rail will transform many regional centres into prosperous and cosmopolitan inland cities. Joyce calls it a “corridor of commerce”. Barilaro agrees. “When I leave politics, the Special Activation Precincts will be at the absolute top of the pile for things that have been achieved for the bush,” he says.

Former Virgin Australia boss Paul Scurrah, now head of the rail freight giant Pacific National, says Parkes and other towns along the line will boom. “It will be a major growth story for the country,” Scurrah says. It’s enormous, up there with the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme and the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Welcome to one of Australia’s largest-ever infrastructure projects that nobody in the city has ever heard of.

And yet, after years of planning and studies – and as the tracks are being laid, land is being resumed and businesses are relocating – a spanner has been thrown into the works. Joyce, newly reinstated as the federal transport minister, says he has decided the Inland Rail should extend to the port of Gladstone – with a spur, probably from Toowoomba, but possibly from Goondiwindi – adding at least an extra 500km of track, and many billions of dollars, to the project. Joyce says this will solve some of the problems in the original plan – particularly that the Inland Rail ends at Acacia Ridge, a southern Brisbane suburb. It means that to reach the port, 30km away, containers would have to be transferred onto the existing commuter line, or loaded onto trucks. “There were a range of difficulties that I became aware of when I returned to the ministry,” Joyce says. “And I am working as hard as I can to iron them out.”

The Gladstone option will open up new coal precincts, he continues. “There, I’ve said it, the dirty word – coal.” There are substantial coal deposits in the Banana Shire, inland from Gladstone, and in northern NSW around Ashford, and Joyce says these projects could become viable if billions are spent on a rail spur to Gladstone. This latest push comes despite a 2020 federal government report finding that the extension to Gladstone was “not economically viable” given the projected $5 billion cost.

Labor Senator Glenn Sterle is deputy chair of the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee, which recently handed down another report called Inland Rail Derailed from the Start. It claims that political decisions have hindered the project and that there has never been proper consultation with the transport industry. Sterle says this led to the decision to end the line at Acacia Ridge, which would lead to thousands more trucks moving through Brisbane’s southern suburbs. “Unless they go back to the drawing board and consult, this is in danger of becoming the longest line of rust in the world,” says Sterle. Joyce, he says, has been “caught with his daks around his ankles – Barnaby buggered this up to start with… it’s a $14.6 billion project, and counting, and we don’t even know where it is going to finish.”

Keith has issued a plea to the current mob in Canberra, including Joyce. “Just get the line built to Brisbane so we can get on with things,” he says. “This is too important a project for Australia for it to get bogged down in petty politics.” Barilaro agrees. “I’d welcome the extension to Gladstone, but let’s get the bloody Brisbane bit finished first.”

So we head to the NSW regions where building is underway or soon to begin to see if the great promise of the Inland Rail is delivering. In an old sheep paddock a few kilometres out of Parkes, along a brand new road called Ken Keith OAM Drive, Paul Hopwood sits in the demountable offices of Pacific National’s intermodal hub, a fancy name for a place where trucks can pick up and drop off containers to go on trains. Each day massive cranes are used to stack and unstack containers and, in years to come, this will become one of the busiest freight hubs in Australia. Trains that come from Sydney over the Blue Mountains can only be single-stacked with shipping containers because of all the bridges. Here at the Pacific National hub they are double-stacked for the journey to Perth and Adelaide. When the southern line is fully upgraded, they’ll be double-stacked for the trip to Melbourne, and then, later, Brisbane – making the trains taller and longer. And, in reverse, trains from those destinations will be single-stacked here for the Sydney leg.

“We haul for everyone,” Hopwood, the local manager, explains. “We cart for Toll, Linfox, Australia Post… we’ve got everything from toilet paper to washing powder, fridges, ovens, packs of timber, plaster, tiles, car tyres, truck tyres… There’s a lot of refrigerated ham and meat and all kinds of groceries. Everything.” Pacific National has purchased a 300ha block within the precinct, and big supermarkets and drink manufacturers are looking to put their distribution centres in Parkes.

Hopwood has lived and breathed this project for the past few years. He has difficulty explaining to his mates just how transformational it will be. “Even with some of the blokes who work here – they’ve been born and bred here – it’s hard for them to comprehend what’s coming for Parkes,” he says. Already businesses are coming. A few kilometres away a new pet food processing plant is nearing completion. It will employ around 130 people, mixing local grains with meat products to make cat and dog food, which will be sent around Australia by the container-load. And it’s understood an announcement is soon to be made about a new recycling plant. Trainloads of sorted waste – some of the stuff we used to ship to China – will be brought here in shipping containers to be transformed into new and valuable products at a state-of-the-art recycling plant powered by cheap energy from nearby solar farms.

Hopwood’s boss, Pacific National’s Paul Scurrah, describes Parkes as Australia’s Memphis – and not just because it hosts an annual Elvis Festival. Memphis, he says, is the rail, road and airfreight logistics hub of the US. “Because of its unique location, we refer to Parkes as Memphis Down Under,” he says. “Parkes is where North South meets East West.” But equally he is excited about the prospects for other towns with industrial hubs along the corridor. “You can take the raw product in by rail and ship out the finished product by rail and go anywhere in the country – it’s super exciting.” The other big winner will be Toowoomba, which will become the main distribution centre for southern Queensland. With its new airport, goods will arrive by train and be exported by plane.

Not everyone is super-excited about the prospect of giant double-stacked freight trains hurtling through their paddocks, or their suburbs, at 115km/h. In Brisbane, the Residents Against Inland Rail Line group is protesting about the increased number of freight trains. Meanwhile, Queensland dairy farmer Wes Judd is leading the Millmerran Rail Group, which is vehemently opposed to the Inland Rail’s proposed route across the Condamine floodplain, west of Toowoomba. His is one of a number of groups in NSW, Victoria and Queensland that oppose the rail project. “Don’t Route Our Farms!” say signs strung up on fences across the Condamine flats. The area is some of the most productive and expensive farmland in the state.

“We’ve got no opposition to the project,” Judd says. “If the business case stacks up and it’s good for the nation, we fully support it. The issue here is where they want to put it, which is pure stupidity.” Judd claims “NIMBYs have taken over” and stopped the line from taking what he claims is a more sensible route, somewhere else. “This is a 19km-wide floodplain,” he says. “It’s like crossing a ditch.”

The proposed route follows the existing rail corridor, but Judd claims that when the level of this line is raised, to accommodate the double-stacked trains, it will greatly exacerbate flooding. The Australian Rail Track Corporation (ARTC), which is responsible for delivering the Inland Rail project, says the levels on the existing rail corridor may be raised but that flooding will not increase because there will be vastly more culverts built to allow flood waters to flow.

Judd’s group has been lobbying Joyce to see if he will change the route. That seems unlikely. “Everywhere I go people want the same thing,” Joyce tells me. “Everyone wants it to stop in their local town and no one wants it to run across their country. It doesn’t matter where you take it, someone wants it somewhere else.” He says the most likely outcome is that it “will go from point A to point B in the most efficient way”.

It’s an issue that will be resolved one way or the other very shortly as work on the 216km section from the Queensland border to Gowrie, on the outskirts of Toowoomba, is set to begin next year. At Toowoomba, a 6.2km-long tunnel will be cut through the Great Dividing Range, big enough to take double-storey trains, for the run down into Brisbane. The Queensland and Federal governments have signed a bilateral agreement to get the line to Acacia Ridge in the city’s south.

As for that inherent flaw – the 30km of missing link to the Port of Brisbane – former deputy prime minister John Anderson, who in 2015 chaired the Inland Rail Implementation Group, says the existing rail link and trucks should be sufficient for the next few years, but that as the population increases an underground rail link will need to be built to the port. He says that when he examined the plan six years ago, there was “no viable business case” to go to Gladstone.

But while some farmers and residents are angry, the mood in the towns and regional centres is more optimistic. Ron Campbell, the mayor of Narrabri – 380km north of Parkes – says the population of the town is expected to double to about 16,000 people in 10 to 15 years. Like Parkes, Narrabri will get a huge Special Activation Precinct. The emphasis here will be on attracting energy-hungry industries to take advantage of its nearby gas fields. “A lot of businesses want to open up on the wellhead because it costs a lot of money to ship the gas elsewhere,” Campbell says. “We’ve got over $7 billion of state significant projects happening here in the next six years. It’s all on the back of having reasonably priced energy attached to the Inland Rail.”

The big challenge, Campbell says, will be enticing thousands of people to move west to fill the jobs that will be created. “We’ve got to work on our community. For country towns, retaining youth is one of the biggest challenges, and we’ve been able to do that with good, high-paying jobs in the mining sector.” But they are going to need many, many more people. “The best way we can attract young people is to build a community that people want to live in,” he says. “We are looking at all sorts of things to make Narrabri a more attractive town. That’s the key to it. You can advertise all you like, but people have to arrive here and go, ‘Wow, look at this joint.’” It’s an exciting time to be mayor, he says, because there is so much happening. “The funny thing is, no one knows about it. When you go to Sydney people say, ‘What’s the Inland Rail?’ It blows me away.”

Each day Narrabri woman Mel Elms drives to Moree where she works on stakeholder engagement for the Inland Rail. Her husband works as a logistics manager for a large cropping operation and they live on one of its farms outside Narrabri. They have three kids, one in primary school and two at boarding school in Toowoomba. Elms tells me about 250 people are currently employed out of Moree, racing to finish the upgrade of 50km of track that runs to the south, halfway to Narrabri, before the harvest. “They have to get it done before the first of November,” she says. “There are three grain trains booked in to run on November 1, so it’s kind of non-negotiable.”

Next year – after the harvest has been hauled to port – hundreds of people will be employed out of Narrabri, upgrading its side of the link with Moree. Hundreds more will be employed, building the line north from Moree to the Queensland border. “I love this job,” says Elms. “I can see that it is going to be transformational for Moree and Narrabri. Firstly, it gets all those trucks off the road – at the moment it is just B-triple after B-triple – and secondly, I think our little towns are going to boom with all this industry and that will bring new hospitals and schools.”

The hope, right along the line, is that the Inland Rail will bring good, permanent jobs. Steve Warburton runs a team of fencing contractors out of the Aboriginal settlement of Toomelah, up on the banks of the Macintyre River which marks the border with Queensland. His business, Drillchan, is in the running to win some of the contracts to fence the new sections of rail north of Moree and into Queensland. If he does, he’ll be able to increase his team from four to 12. “If these fellas can get steady work it makes a huge difference not only to them, but to the whole community,” says Warburton. “It’s put a bit of spark in the Toomelah community. I ask these fellas how much they earn – $500 a fortnight they tell me. I tell ’em if they have a bit of a go they can earn $1200 a week.” He says fencing leaves them with good skills that they can transfer into other work places. “You don’t just learn how to put a fence up. You learn how to concrete, how to weld, how to drive machinery…” Warburton’s grand plan is that when the line is completed some of his crew will get permanent work as fettlers on the rail maintenance crews that will be stationed all along the line. “The Inland Rail has given these fellas up here a lot of hope,” he says.

The tiny NSW village of North Star, south of Goondiwindi, has been doing it tough for many years. Over the past few decades the smaller farms in the district have been gobbled up by larger operators and dryland grain farming is now highly mechanised, meaning there are fewer workers required on each farm. As a result the businesses and services in the village have shrivelled and the population has shrunk to 50.

Fourth-generation grain farmer Simon Doolin says it was breaking his heart to see his once vibrant community fade away. “We just never saw our neighbours,” Doolin says. “Me and my mate, James Hardcastle, just got the shits that there were no services in town. There was nowhere for mothers to catch up during the day. There was nowhere farmers would run into each other for a yarn. There was nowhere central for kids to meet up. There was nowhere to get fuel, even.”

The two cockies bought what had been the village’s old vicarage and have spent almost $400,000 renovating it into a cafe, shop, hairdresser, playground, restaurant, beauty salon, servo and pub. “I just got an email this morning confirming our grog licence… Look at our bar,” he says, like a proud father pointing out his newborn. The Vicarage’s bar, a simple tin shed, sits in the garden. “I’ve got a cement truck arriving next week to pour a slab – isn’t it beautiful?”

The idea with the entire venture, Doolin says, is not to lose too much money. “We hope we can break even and if we do make a profit we’ll plough it back it into improvements. All of the tables have been donated by locals, everyone wanted to put money into it. The goal is to revitalise our community.” It’s given the village a new lease of life. Doolin says they’d like a well-known artist to create art works on the village’s giant grain silos.

Next year, work will begin on the 125km-long track between Moree and the Queensland border. It’s likely that a workers’ camp will be established in the North Star showground, the base for hundreds of workers over the next couple of years. The Vicarage will be their watering hole and for a time North Star will be a party town. The influx of patrons will go a long way in paying back the debt to the owners and likely make their little community hub an ongoing proposition. At the time of my visit, it had been open for only two weeks and was already making a difference.

“We had a couple of people in here the other day who hadn’t seen each other for years,” Doolin says. They’ve now arranged to meet up for a regular coffee date. “We’re rebuilding a community,” he says. “It’s pretty special.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout