Ian Smith, the lobbyist who found a cause: refugees

He’s from the shadowlands of the conservative establishment, but it was in a refugee camp in Africa that Ian Smith saw Australia’s arrogance.

Heavy rain has fallen on Kakuma refugee camp and the alleys are paved with mud and cholera. Every year for the past five, Ian Smith has wandered past the mud-brick huts in the camp’s “Hong Kong” precinct, past the United Nations toilets and rock-hard yards, children poking and touching his middle-aged skin. White faces are rare in the hundreds of vein-like alleys and main streets where the mainly South Sudanese community trades in camp commodities and gathers at the corrugated iron “Hilton Hotel”. Kakuma spreads for kilometres in each direction in north-east Kenya and from here it’s a short drive to the war in South Sudan.

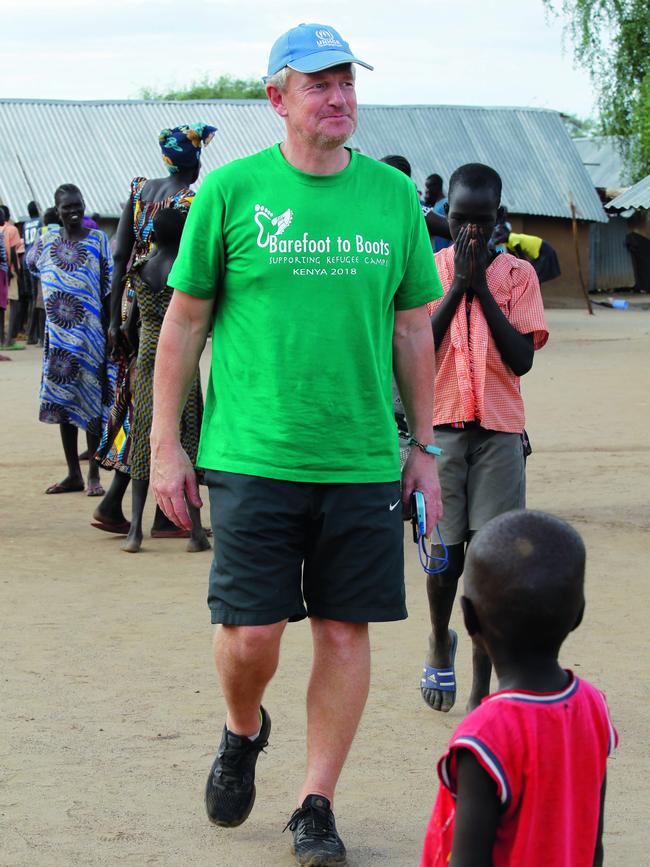

Smith, the 52-year-old adopted son of Australia’s conservative political and business establishment, and husband of former Australian Democrats leader Natasha Stott Despoja, is walking with the man he calls his son, Awer Mabil, and the man he calls his brother, Awer Bul. “It’s changed my life, it will never be the same,” Smith says of the start-up charity he has formed with the two men, Barefoot to Boots.

Smith is one of the nation’s most influential back-room lobbyists, helping steer multiple governments, Telstra, BHP, ANZ, James Packer’s Crown Resorts, Qantas, Foster’s and the Pratt family through crises. A relentless networker who cut his teeth working as a spin doctor for Jeff Kennett, he’s been a friend and adviser to prime ministers and premiers, confidante to billionaires. But after a shift in direction he’s spending more time outside the boardroom and the ministerial wing at Parliament House, focusing his attention on the world’s largest underclass, the 69 million-strong refugee family.

For many years before making their way to Australia, Mabil and Bul had lived the life of Kakuma. Dirt floor huts, no power, a drop dunny in the yard. Mabil, 22, is now an emerging international soccer star who arrived in Adelaide in 2006 with his family via Australia’s humanitarian immigration program. Today he is treated like a rock star in the camp. His brother Bul, 35, is one of the 40,000 Lost Boys of Sudan, who walked for several years across the African desert dodging bombs, soldiers and crocodiles to Kakuma in 1994, eventually landing in Australia via the US as a humanitarian refugee.

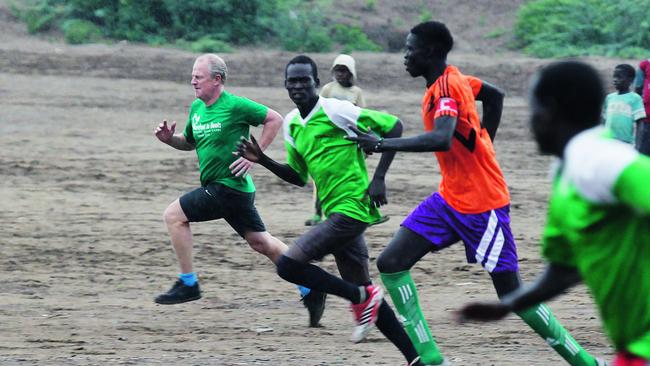

Smith met Mabil while the then teenager was playing for Adelaide United FC and Smith was on the board. Then a precocious young talent, Mabil approached Smith in August 2014 to ask if he could help him and his brother give back to their homeland. It was a meeting that gave birth to their charity, which has overseen the donation of more than two tonnes of soccer equipment to the hundreds of teams of children and adults who compete on dirt pitches at Kakuma.

For Smith, the path to this refugee camp and others around the world has been transformative, and he has been increasingly recognised for his efforts. He was awarded an Order of Australia this year for his good deeds. “I find a conversation with a young refugee who is wanting to have a good life far more invigorating than talking to most politicians,” he says. “They are much more interesting people in many respects, and that’s not to denigrate politics or business leaders. Here the conversation is so rich and different and life and death.”

Unlike his wife, Smith is not a household name. His work as a lobbyist, in its own way, demands a level of anonymity. Of his greatest strength, he says: “I don’t know a lot but I know a lot of people.” His politics are right-wing Liberal but his friends — and wife — have often crossed the political divide and he has never been a card-carrying member in Australia.

For all the financial benefits that have flowed from the shadowlands of lobbying — million-dollar seafront views, Range Rovers and Gatsby-esque birthday celebrations — his conversion has been in Kakuma. His views often clash directly with the hard-nosed messaging of the Australian political classes, which he accuses of exploiting misery and failing to take a common-sense, economics-based approach. His lobbying on these issues is generally discreet. No megaphones. Direct discussions. Of hard line politicking on race and immigration, Smith says: “I loathe it, hate it. I hate the extremes.”

Awer Mabil and Awer Bul weren’t to know that the vision to provide soccer boots and shirts to the thousands who play the world game in the 180,000-strong camp would evolve into something bigger. They delivered the idea, Smith the contacts and political and bureaucratic acumen; beneath them is a board including former Qantas chair Margaret Jackson and Melbourne philanthropist and businesswoman Louise Steinfort. It helps the charity greatly that Awer is one of Kakuma’s success stories; he plays in Europe, and last season was with Paços de Ferreira in Portugal’s first division. “I call him the connector,” Bul says of Smith. “He knows many people.”

Former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright, who has a business relationship with Smith through her advisory firm, is among those who acknowledge the role he plays in the debate around refugees. “He [Smith] is passionate about engaging business more strategically and over the long term to invest in camps as well as influencing governments so they can develop more sustainable refugee policies,” she says. “The movement of refugees is not a crisis any more but a permanent state of affairs. We must think differently about it.”

Smith, who’s based in Adelaide, wants governments to embrace a more productive approach to humanitarian work that engages the private sector more fully and creates economic opportunities to enable residents to work and build financial futures inside and outside the camps. Kakuma is emerging as a test case for an economic solution to displacement, with corporates including Microsoft and Vodafone circling the region for opportunities to provide digital infrastructure. It seems every refugee has a mobile phone.

Smith loathes the political language around refugees, an issue that has been exploited by both sides of politics, rendering toxic a debate that, he says, misunderstands the motivation of the dispossessed. “You give a refugee the chance to succeed and they will take it,” he says. “When we look at our own policies we tend to look at a sense of fear and some sort of trepidation rather than embracing the proven contributions of refugees. I think it’s because we’ve got views that are terribly ill-informed. It’s not as if everybody’s wanting to jump on a boat to come to Australia. I have met hundreds, if not thousands of refugees in camps and settlements and perhaps four or five have said: ‘Can you get me to Australia?’ They want to be close to their place of origin when safety returns. In fact, it’s terribly arrogant of Australia to think we want to be the end point for every refugee in the world. They don’t. They want to return home to safety. This is where investing in camps and host communities or host countries is so important and I don’t think we do enough of that.”

He says the Manus and Nauru models were doomed to fail because they offered no serious economic opportunity for the residents; he’s calling for those on the right of politics to mobilise. “I think there is an enormous opportunity for people who sit slightly to the right of politics. The principles are very simple. Entrepreneurship — encouraging individuals to succeed.”

He’s also concerned about the African crime debate in Melbourne and the potential for long-term harm in the Sudanese community if attempts aren’t made to understand the context of the offending and the achievements of the broader community. “Having seen the resolve and the work ethic of thousands of refugees in camps I am strongly of the view that what they give Australia is profound,” he says. “To marginalise them through simplistic commentary will seriously overshadow the overwhelming positives they bring.”

For many in Kakuma, life is lived on the edge. Inthe late afternoon, a young woman is belted repeatedly with a cat o’ nine tails whip in full public view on a camp road as the charity’s borrowed United Nations four-wheel-drive returns to its home compound. The attacker is a man; the victim falls to the ground and he lays into her, leaving her cowering on the road. The attacker has a big machete slung across his back. At risk of being attacked himself, our driver slowly passes, guessing the victim is Ugandan and the dispute is about moonshine being brewed in the camp.

A shanty city with the same population as Albury-Wodonga and Ballarat combined, the school and health facilities here are depressingly underfunded. The sick are likely to remain sick. The power of even a start-up charity to make a difference is exemplified by the two incubators donated to Kakuma General Hospital for premature babies; worth about $12,000 in total, they have already helped save 25 lives in six months. Before they arrived, the hospital was wrapping the dying children in blankets and hoping for the best.

As well as medical supplies, the charity has a private sector partnership with Australian company GenesisCare to supply sanitary kits to women and girls; it also opens up a dialogue with girls attending schools in which the student-to-teacher ratio can be up to 200-to-one. A growing focus of the charity is improving conditions for women and girls. Sex assaults, backyard abortions, domestic violence and genital mutation are some of the challenges they face.

Smith is talking to Indian-born billionaire Sanjeev Gupta about building an oxygen plant in or near Kakuma to supply the hospital and camp. (At the moment the hospital must import oxygen from hundreds of kilometres away.) It could be staffed by refugees, giving them an income and the opportunity for economic advancement. The camp is heaving with hundreds of small businesses, ranging from hairdressing salons, clothes stores and mobile phone outlets. All based in shanties. His charity is helping educate the young with reading, writing and maths skills to capitalise on the global push to provide economic opportunities for the dispossessed. “We need these people to be able to access the broader economy, so they can grow and build their futures,” Smith says.

Smith was raised in England’s stockbroker belt by Tory-voting parents and educated at the private City of London Freemens School. He studied journalism in England before emigrating to Australia aged 22 to play rugby in Wagga Wagga, where he worked on The Daily Advertiser.

Soon after, he moved to The Advertiser in Adelaide, where he rose through the ranks to become national editor, which involved managing Canberra and other interstate copy under the guidance of editor Piers Akerman, a bulldozing News Corp editor and conservative columnist. Akerman and Smith saw politics through the same prism. Smith’s first job after journalism in the late 1980s was hosing down crises sparked by his boss, the late South Australian Liberal leader Dale Baker, whose (often Grange Hermitage-fuelled) misadventures included making pig noises over a loudspeaker at police while on a charity car run.

Smith distinguished himself as a press secretary by unintentionally leaking a cabinet reshuffle while at lunch with the late editor of The Adelaide Review, Christopher Pearson, who proceeded to break the news to a soon-to-be-ex-frontbencher at the Liberal Party’s Christmas drinks.

Andrew Male, a former Adelaide journalist and Liberal adviser, remembers a young Smith roaring around town in his Savile Row suits, braces and brogues with single-minded determination. His energy was devoted to the cause of the minute, the white noise of life blocked out. “He wouldn’t bother to return a non-client call if he assessed that you/we were not dying or being held to some magnificent ransom by a gang of mercenaries in the uplands of killing country,” Male says. “Smithy’s oldest friends won’t hear from him for many seasons. Still, I think all of his friends believe on good grounds that if Smith thought a mate really needed him, then we would all trust that he was already quietly organising three aircraft carriers.”

Kakuma’s Hong Kong is a long way from Jeff Kennett’s Victoria in the early 1990s when Smith bounced into Spring St and into the ministerial media unit, later declaring he’d helped rid Victoria of its rust-belt status. The Kennett government was a corporate nursery; many young staffers went on to senior business roles across the globe. Relentlessly ambitious, it was not long before Smith had all but secured a job with Crown casino in government relations, as gamblers poured billions through the front doors on the Yarra River.

John Wylie, Rhodes scholar, investment banker and philanthropist, was running Credit Suisse First Boston in Melbourne after a stint in New York. The Smith he knew had by then graduated to open-top sports cars, a bachelor pad in South Melbourne and an eye on much bigger prizes. “Because of his personality, he’s had a capacity to reach across both sides of politics,” Wylie says. “And he doesn’t make any secret of the fact he is a loud and proud Tory. But he’s got a capacity to talk and be on the same level as anybody.”

When Smith started dating Stott Despoja in late 2001 it rocked his inner sanctum. Few could imagine how a child of the British Conservative Party could find himself with the leader of a centre left party, whose politics were focused on opposing the Howard government. Their relationship was fireproofed as Stott Despoja fought in 2002 to save her leadership and the party that made her; now, 16 years later, they have two children and are a national power couple. Stott Despoja, 48, is a board member, advocate and former ambassador for women and girls.

They share a passion for politics, close media connections (her mother Shirley is a veteran journalist with a high profile in Adelaide), high energy and a wary fascination with TV and print journalism, but beneath it all is an interest in humanitarian matters. “Ian and I were often asked what policies united us. Always one answer was refugees,” Stott Despoja says. “Ian witnessed early the appalling treatment of refugees and asylum seekers by a government when I was involved in the Tampa issue. He knew this was a deal-breaker issue for me in a relationship.”

Stott Despoja credits the Kakuma brothers with providing a channel for Smith to pursue the agenda, adding: “Ian is one of the most gregarious and generous souls I’ve met. It was just a matter of determining how to focus that spirit and coming to grips with the politics of the issue.”

Kakuma is dripping in 33ºC equatorial heat as afleet of UN vehicles pulls up outside the refugee camp’s reception centre. Smith has helped drag a cross-party political delegation, with Australian High Commissioner to Kenya Alison Chartres as guide, all the way from Canberra to the local refugee centre and hospital, where Barefoot to Boots gets a glowing rap from the administrator.

Victorian Labor MP Tim Watts hands over a bag full of soccer gear to the charity; MPs Andrew Broad, Luke Hartsuyker and Graham Perrett look on as Smith takes charge of allocating breakfast to dozens of refugees lined up to have their names ticked off. Watts has shown an interest in a Canadian policy of individual communities directly sponsoring refugees. “Smithy reached out to me after that; it gels with his way of thinking on the issues,” he says. “It’s kind of anti-politics.”

At the hospital, a young mother is queuing with a three-month-old malaria patient. Smith picks up the child and talks quietly to the women around her. This is Smith’s second meeting on the trip with Our Woman in Nairobi; the first was an informal lunch at the home of the UN Resident Coordinator to Kenya, Siddharth Chatterjee, the son-in-law of former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon. Everywhere there is a connection.

Another is with rapper Octopizzo, a child of Nairobi’s slums. Smith met him in Kakuma in 2015 and they’ve become the unlikeliest of friends, trading phone calls, tweets and ideas about helping these communities. One Saturday night Octopizzo leads Smith, dressed head to toe in Ralph Lauren, through one of Africa’s worst slums. Five white people, the rap star, Bul and Mabil and two bodyguards. Past the bars, the congregation of the Blessed Prophetic Miracle Ministries, the Hotel Gracious and our Lady of Guadalupe, past the thump-thump of the engines grinding maize, over rubbish heaps as sewage pours down the alleys.

Octopizzo suddenly turns a hard left, into a shanty that acts as a hotel. The corrugated iron and mud hotel’s second room is big enough only for a bed. The front room measures four metres by two and a half metres; there are a few iron pots cooking on charcoal, a tub for water and bench space to wash some dishes. “This is my home,” he says. “This is where I grew up.”

With everyone crammed inside, Octopizzo talks about life in the slums before the dirt floor is filled with the wretched contents of the drain outside. “The community is so nice, there are no thieves. There is just mob justice,” Octopizzo says. “For this place there is always a war but it’s a different kind of war.” It is a war that Smith is convinced will ultimately be won or lost by business.

John Ferguson travelled to Kenya courtesy of Helloworld Travel, a supporter of Barefoot to Boots.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout