‘I care deeply about the future of the planet’: how gallery chief balances climate with culture

She’s the first woman to be appointed director of London’s venerable National Portrait Gallery. How will Victoria Siddall – a climate crusader – navigate the tricky world of art, influence and politics?

Well, Oscar Wilde did moot that life imitates art, rather than the other way round. So it seems only fitting that two years after Tracey Emin designed 45 female faces to go on the new bronze doors of London’s National Portrait Gallery (a foil to the 14 stone heads of white all-male painters sitting just above), the gallery should appoint its first ever woman director after a run of 12 men.

Victoria Siddall, 47, the former global director of Frieze art fairs, is sitting in her office looking out to the historic building in London’s Covent Garden and those portals. It’s a gloomy day but the bronze glows, and so does Siddall, even if she is fighting off a cold.

I tell her that I was reminding myself of her 12 predecessors, from Sir George Scharf to Dr Nicholas Cullinan, now director of the British Museum, and was genuinely moved to see her name at the bottom of the list. There are plenty of female gallery directors in the UK, the most prominent being Maria Balshaw at Tate, but the appointment still feels momentous.

Siddall nods: “It does. After the announcement of my role I had so many women coming up to me, especially young women who I didn’t know, saying, ‘This really means a lot to us.’ It was very humbling, actually. It was a reminder that these things are meaningful.”

Siddall, small and neat, is the definition of understated elegance in a cream cashmere rollneck, dark tailored trousers and pale jacket. Her hair is held back from her face with matching clips and she wears her trademark slash of red lipstick. She had been involved on and off with the NPG for a few years; in the year before her new gig as a trustee, and before that in voluntary roles, including on the reopening committee in the 12 months running up to the gallery’s triumphant return in 2023 after its £41.3 million ($82 million) remodel. So it hasn’t been a standing start – she already knew the gallery, the collection, the team.

She and Cullinan have been friends for years. They had a joint 40th birthday party and he was her route into the gallery, initially as an adviser. Cullinan’s NPG reign was deemed a triumph. Yet following my meeting with Siddall, he has become the focus of a nepotism row. It has emerged that, while NPG director, he agreed to a display at the gallery by the photographer Zoë Law, who was a trustee of the Law Family Charitable Foundation, an NPG donor, until June 2024 (her portrait of Oasis frontman Noel Gallagher has also been donated to the gallery for its collection). The gallery confirms that the opening party for Law’s display happened in Siddall’s first month in the job and that she attended, but insists the deal was done well before she worked there and went through their ethics committee. Meanwhile, Siddall is keeping schtum. At the very least it sounds a little cosy.

Talking of cosy, did Cullinan give her an early tip-off that he was leaving? “Nick is extremely discreet but when that job [at the British Museum] came up I immediately thought of him,” she says. “So, without a word from Nick, I thought it might be him and hoped it might be him because he’s really deserving of the role and he will do really exciting things there.”

While at Frieze – which started as an art magazine and became one of the coolest and most influential contemporary art fairs in the world – Siddall set up fairs in LA and Seoul and started Frieze Masters, a historical art fair with a modern sensibility. Since leaving in 2022, she has not exactly bunked off. She has been a consultant at Tate, set up two art world climate change initiatives (of which more later), and been a trustee of Studio Voltaire, a studio complex and non-profit gallery in Clapham, southwest London. But, as she puts it, “It wasn’t one big job. And I thought, ‘What could that be after Frieze and the various things I’d been working on?’ And the more involved I became [with the NPG], the more I realised it was what I wanted to do with my life.”

More change is afoot. Dr Alison Smith, the highly regarded chief curator at the NPG, responsible for the upcoming Edvard Munch show, has just left for the quiet treasure that is the Wallace Collection. Siddall will be interviewing for her replacement soon.

The collection does require a serious marshall. At its core there are around 12,700 works, and, alongside that, a photography collection of 250,000 works. A relatively small portion of the collection is on display at any one time. The Tudor rooms, with its eternally popular selection of regal portraits from 1485 to 1603, will stay as they are. Elsewhere, expect more shuffling and future-proofing. “It is a real advantage to rotate, move things around, take advantage of the collection, so the chief curator role will be very involved in that,” says Siddall.

There will be other rotations too. David Ross, the business titan and chair of trustees who helped make the makeover of the gallery happen, also departs in October at the end of his eight-year term. It’s arguably as significant a loss as that of Cullinan. His replacement will be a government appointment.

“He has been very supportive of the NPG and the team, and,” she adds, smiling and gesturing out of the window, “of himself – we are looking out to Ross Place! The new chair will go through the DCMS [Department for Culture, Media and Sport] public appointments process, so it won’t be my appointment necessarily, but I am very mindful of how important the relationship is between the director and the chair and how it’s essential for the institution to flourish.”

I hate to be the voice of doom, but I say I hope she is prepared for the worst and has a cap ready to shake. Does she remember how, when Lisa Nandy became Britain’s Culture Secretary and declared her joy at being in charge of the “ministry for fun”, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves gave a chilling riposte, however tongue-in-cheek: “Fun is cancelled.” Siddall laughs. “It is [tough], but there are also really compelling arguments for supporting culture, partly economic benefits,” she says, with the sort of Pollyannaish determination that she is going to need.

She talks about the benefits of the arts to physical and mental health, and later points out that the refit has resulted in far more visitors with disabilities coming through the doors – a 133 per cent increase since the reopening. Few would disagree that this is all terrific, but the NPG got almost £11 million from the Government in 2023/4 (and £8.8 million in donations and legacies), about a third of what its neighbour the National Gallery receives. Cullinan didn’t achieve a grant hike. Will she manage it?

“That would be wonderful,” she says, “but also there are responsibilities as a director to think of other ways that we can generate revenue.” She certainly has a reputation for that. One art world figure tells me how impressive she is at fundraising at parties, talking to everyone from philanthropists to artists to punters. It makes absolute sense that the person in charge of a gallery about people and for the people is good with people. Not all have been. Yet some are concerned that her lack of what they see as academic rigour (she did not study history or art history and the NPG is, officially, a museum of history) might make some would-be donors nervous. Siddall is primed for them. “It’s one of the reasons that I’m here because my background, unusually for a museum director, is in the commercial sector and it’s one of the reasons I’m excited.

“I am not an academic – the academic expertise of the team here is extraordinary. I am in awe of the incredible knowledge and curatorial expertise, but that is here already. What I am bringing is different and it is an interesting moment, as I am, as you say, a different mould for a museum director, but I think that it is one very suited to the times we live in, and I am excited about partnerships and collaboration and how we think about how a museum can be in the future.”

Will she be able to ensure that entry remains free? [A pertinent question here after one of our major galleries, The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia last month introduced a general admission entrance free of $20]. “Yes. It is such a unique benefit and if we believe as a country that it should be for all then welcoming visitors through the doors of a museum regardless of their means is a real testament to that commitment.”

Of course, in 2025 it’s not just about attracting money but about attracting “the right kind of money” and money without awkward controversies attached (see the Zoë Law display). Last year nine book festivals in the UK, all previously sponsored by Baillie Gifford, ended their relationships with the investment company following calls by the campaigners Fossil Free Books for the company to divest from fossil fuels and companies linked to Israel.

The NPG ended its sponsorship ties with BP in 2022, by mutual agreement. The gallery’s Portrait Award, once sponsored by BP, is now funded by the law firm Herbert Smith Freehills.

Since leaving Frieze, Siddall has set up Murmur, an organisation aiming to unite the art and music sectors to raise funds and advocate for solutions to climate change. She is also a co-founder and trustee of Gallery Climate Coalition, an international community of arts organisations working to reduce the arts sector’s environmental impacts.

Would you accept BP’s dosh now? “It’s a hypothetical question,” she says, shutting down the conversation like an old pro, but never saying never. In 2023, the British Museum accepted £50 million from the company towards its £1 billion 10-year master plan for renovation. “The arts and museums have got a really important role to play in addressing the major issues in the world and as you can see from my previous work, I care deeply about the future of the planet,” she offers.

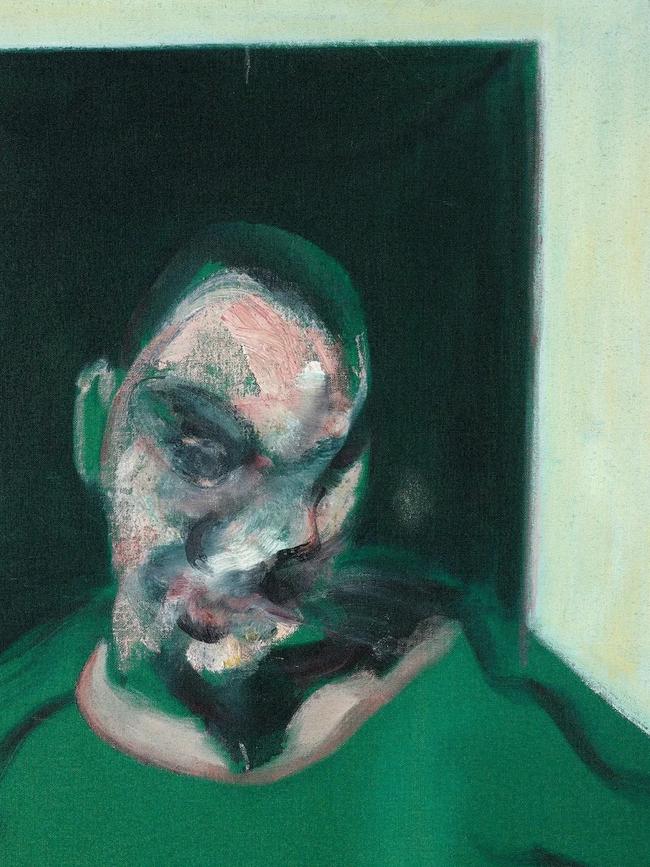

She is rightly full of admiration for the recent Francis Bacon exhibition, which attracted visitors from around the world and which The Telegraph’s critic declared to be “as powerful and perverse as the man himself”. Yet it was made up entirely of loans, many works arriving on gas-guzzling planes. And she also speaks of taking whole exhibitions abroad, to push the NPG overseas. How does this shake down? Will she restrict herself to one carbon-heavy show a year and pack the other shows with works from the basement? “It’s a really good question and all museums are thinking about this at the moment. In isolation it is difficult for one organisation to make those changes, it needs to be industry wide – and across the commercial sector too. Museums in New York are having the same conversations and collaboratively we will come through.”

One of the greatest examples of collaboration is the deal brokered by Nicholas Cullinan to keep the magnificent 1776 Portrait of Mai (Omai) by Joshua Reynolds in the country. In the end, it was bought by the NPG and the Getty museum in Los Angeles under a sharing agreement. “He kept [it] in his studio his whole life, he didn’t sell it, and it is also, to my knowledge, the first regal, courtly painting made in this country of a person of colour overseas who was embraced,” she says. She calls the Omai agreement a great example of “soft power”.

So which work would Siddall bring in if she had a fantasy budget? She pauses. “We don’t have a Francis Bacon painting in our collection.” And in a sign of her powers of persuasion, she reveals that, within three months of her arrival, she is in discussions to secure for the gallery the long-term loan of a Francis Bacon.

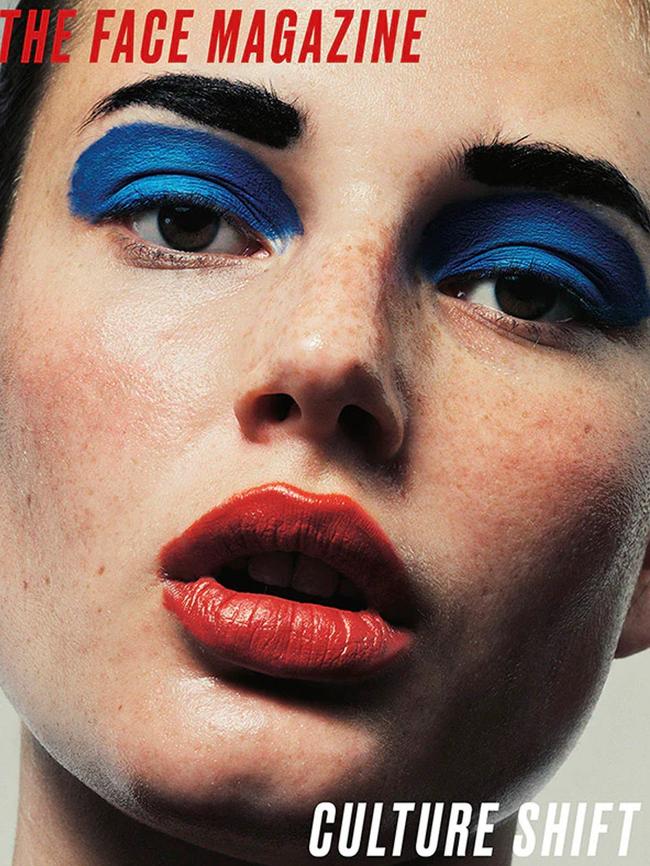

Although Siddall’s own ideas for shows won’t filter through for a couple of years at least, there’s plenty on the slate for the NPG. This month a show about the pop-culture magazine The Face opens: “The exhibition is focused on the 1990s and for those people who were here at that moment they will be very excited to see it,” she says. After that, there’ll be an exhibition of portraits by Edvard Munch. Then, in June, the first major UK show of the painter of bodies Jenny Saville. Come autumn we will be invited into the social whirl of Cecil Beaton with a show dedicated to his career.

Presumably, Siddall will join the 12 former directors in having her own portrait painted or shot. She confirms that it is an NPG convention. The two portraits of Cullinan held in the collection were acquired as gifts from the artists. In Siddall’s case, as with any commission, they would work with the sitter to discuss the choice of artist. But what story would accompany it? Siddall was born in 1977 in Belfast into an Army family – her father Stephen was stationed there; her mother Jill served too, stopping when Siddall came along. She has a sister and a brother. Her childhood, a subject she seems a little reluctant to get into, was peripatetic. Each time the family was relocated – she also lived in Germany and Washington DC – she moved schools, until the age of eight when her father was stationed in Zimbabwe, and she was sent to a boarding school in the UK. She says she wasn’t particularly artistic but was a bookish child who went on to study English literature and philosophy at Bristol University.

“It was only after moving to London in 2000 that I really got to understand art and museums,” she admits, refreshingly. She mentions being blown away by Wolfgang Tillmans’ show in 2003 at Tate Britain and the 2005 Frida Kahlo show at Tate Modern.

As a box-fresh graduate let loose in the capital she started working at Christie’s, writing business proposals. It was the start of her informal art history training, working with the auction house’s departments – one day Impressionism, another day Furniture. “It was an interesting insight into art history but also the art market.” She stayed for just under four years and then went to work for founder Matthew Slotover at Frieze in early 2004. “Just around the time of the first fair in October 2003; it changed the city and galvanised it and it felt like a celebration of London and I thought: ‘I want to do this.’”

She lives in southeast London with her long-term partner François Chantala, a founding director at Thomas Dane gallery. They have an eight-year-old daughter. Has she brought her here? “Oh yes, many times. She has test-run some of the family workshops.”

We discuss another mother of young children, the NPG’s patron, the Princess of Wales. Siddall considers her “very expert in art history and passionate about art. We are lucky to have her.” The feeling is mutual, I am sure. The Princess’s first solo public engagement was to the Lucian Freud Portraits exhibition at the NPG and she worked with the gallery on the Victorian Giants show in 2018. During the Covid-19 lockdown she set up a project, Hold Still, to encourage people to send in photographs of their loved ones. When I ask Siddall whether they will get together to hatch plans, she says they are “just beginning that process. We are really looking forward to welcoming her back.”

We are running out of time. I look around at the walls of her office, whose previous incumbents include former directors Cullinan, Sandy Nairne and Charles Saumarez Smith. She catches me and looks mildly panicked. None of the works on the walls are her doing, she says. “Don’t read anything into them!” OK! But Prime Minister Keir Starmer has chucked out a Margaret Thatcher portrait at No 10. What would she bring in? She says she would never take a work that’s on display, but if she could, she might nab the painting of Ada Lovelace by Margaret Sarah Carpenter in Room 16, part of the Government’s art collection. “The portrait looks like a society beauty but she was essentially the first computer programmer. It’s a wonderful juxtaposition of image and narrative which takes you by surprise,” she says.

A society darling with an excellent brain? Reminds me of someone.