‘Huge confusion’: The great masses swap parties in the USA

Democrats and Republicans have switched sides - and nearly half of voters now call themselves independent. Meet the politically homeless.

In 2016, Shelle Lichti voted for Donald Trump. She got tons of blowback from other gay people who thought she’d betrayed them.

She was 45 at the time, and she’d been doing things her own way since she was 11, since she was adopted by the big Mennonite family in Missouri, and ran away, and came out, and became a trucker, hauling beef and pork across the American hinterland in a rainbow-painted 18-wheeler. It was tough being a woman. And a lesbian. But she’d forged a new life for herself.

She had built a portable home in the back of her truck – with a kitchenette, curtains, warm little lights, a generator and her bed on the lower bunk, and all her clothes, first-aid gear and dry goods in the top bunk – and she’d traversed an array of politics and religions. (She was into Buddhism – the calm, the focus. “I choose to say I have faith, but I’m not religious,” Lichti says.) She liked to listen to audiobooks – she was into Nora Roberts, the romance novelist – and she loved to turn up Sia when she was “laying down some miles”, which meant going for hours and hours, not stopping, pushing on to wherever she was going. What she had learned from riding around the country in her little home in her big rig was you never knew as much as you thought you did about other people. “Everybody is on their own ride,” she says. “We have to respect that.”

Over the years, she noticed the homophobia had waned, but it had gotten harder to make a living, mostly because of the influx of truckers, most of whom were from Somalia and the Middle East.

“I don’t have a problem with them – they’re out here making a living for their families,” Lichti says. But with the new truckers, it was harder to get a raise. “When I started” – in 1993 – “I made 19 cents a mile. Now, I barely make double that.”

It wasn’t just Lichti who was struggling. It seemed to her like the country was falling apart. “A lot of roadside motels and hotels look like crack houses,” she says. “Not enough people coming through.” On top of that, she says, Main Streets everywhere had been devoured by Walmart, Costco, Amazon. “The billboards on Route 66” – the 4025km highway connecting Chicago and Los Angeles – “are mostly gone.”

Then, in June 2015, Trump announced his presidential bid, and the bluster, the fireworks, the who-gives-a-f..k about sticking to your talking points – that was refreshing in the face of all the decline. A lot of her gay and lesbian friends thought she’d gone crazy. “I was like, ‘If you want to unfriend me because of my beliefs, then you’re no better than the people that hate on us,’” Lichti says.

But after Trump got into office, Lichti started to see the world differently yet again. Trump seemed too nasty in his rhetoric, like a “toddler”, she says. Then, she learned her son was transgender, and it seemed like a dangerous time to be trans or Muslim or Mexican.

“My son’s own twin brother has blown him off,” she says. Then came Covid, George Floyd, the riots. And Trump didn’t seem to make life any better for truckers, Lichti says. “It got even worse.” By Election Day 2020, she says, “I wanted anybody but Trump.”

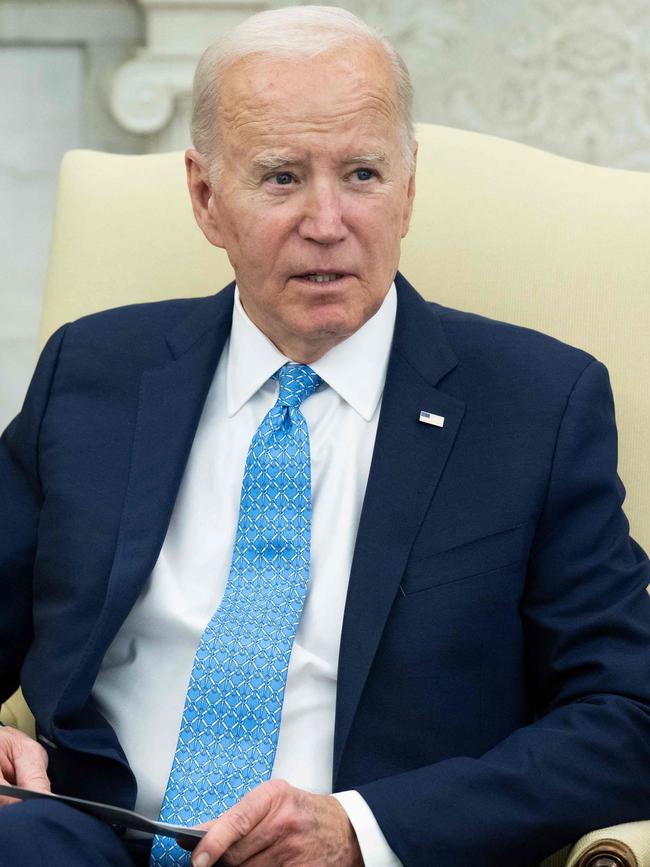

Lichti voted for Joe Biden.

More than three years later, she doesn’t know what to believe. She says she feels unmoored. She considers Biden a “seat-filler”. She doesn’t care for Democrats. She kind of cares about climate change, and she’s pro-choice, and she’s heartbroken about the people dying in Ukraine and Gaza, but she doesn’t think it’s America’s problem, and she can’t stand the kids in the LGBTQ+ movement with their “20 zillion acronyms”. She says she isn’t a “conservative” or “progressive”, and definitely not a Democrat or Republican.

“Our society has made it to where we’re supposed to fit in a certain mould,” she says. “A lot of us, you know, well, it’s like taking a plus-size girl and trying to squeeze me into a size 2. Just not gonna work.”

Shelle Lichti is hardly alone. Nearly half of Americans now identify as independent – not necessarily because they’re centrists, or moderates, but because neither party reflects their views. That’s because, over the past several decades, the parties have switched places, leaving tens of millions of voters unsure about what they stand for or where they belong, says Yuval Levin, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and author of A Time to Build, about reviving the American Dream.

Levin describes two axes in American political life – one right-left, the other insider-outsider. Traditionally, the party of the right has been the party of the inside – the establishment – and the left has fought for those on the outside – the poor, the disenfranchised. “But in the 21st century, they’ve switched sides,” he says. “Democrats are the elites, and Republicans feel like they’re fighting the establishment.”

One way to think about it, says Michael Lind, author of The New Class War: Saving Democracy from the Managerial Elite, is geographic: “From Lincoln to Reagan, New England, the Upper Midwest and the Great Lakes, and the western states were the Republicans, and now they’re the Democrats – while the interior was all the Democrats, and now they’re the Republicans.” This switch has “created a huge amount of confusion, because it’s happened without either party recognising it,” Levin adds. “Republicans have gotten pretty comfortable with it, while Democrats are very uncomfortable being the insider party.”

That’s because it’s “political suicide” to acknowledge you’re the party of the elite, says Thomas Edsall, a New York Times columnist who has reported on national politics for half a century. “Democrats are elite, but they can’t say it,” Edsall says. Consider that, in 2016, the median home price of a Hillary Clinton voter was $US640,000, while that of a Trump voter was $US474,000. In 2018, Democrats took control of the 10 wealthiest congressional districts in the country – all of them on the coast, mostly in New York and California. Of the top 50, they held 41. And, increasingly, Democrats recruit their future leaders – their ideas – from a handful of universities that cater to the American elite. From 2004 to 2016, 20 per cent of all Democratic campaign staffers came from seven universities: Harvard, Stanford, New York University, Berkeley, Georgetown, Columbia and Yale. By contrast, the University of Texas, Ohio State University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison provided the most Republican staffers.

The reasons for the “Great Scramble”, as I call this large-scale political reversal, are legion and stretch back decades, if not longer: the breakup of the Democrats’ New Deal coalition, the end of the Cold War, globalisation, the internet, the decline of organised religion and the two-parent family, the forever wars, the opioid and fentanyl crises. “Things are definitely in flux,” Lind says.

What I know for sure is that I first glimpsed it on Election Night 2022, at a “victory party” in Phoenix for Republican gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake. Lake’s supporters seemed to fall outside the old left-right construct. Racially, economically, ideologically – they didn’t fit the preconceived categories.

My surprise was obvious when I interviewed a Latina in her fifties in an Iron Maiden T-shirt. How was it, I asked, that she supported a candidate who had run against more Latinos coming to America? Had she not seen Lake’s campaign manager’s “racist tweet” a few weeks before?

That’s when she started lecturing me about “gangbangers coming here” and then “Big Tech” and “Big Pharma”, but also her friend’s bi-racial daughter and Martin Luther King Jr, and why Washington should “pump trillions” into the rural parts of the country decimated by fentanyl and cheap overseas labour.

Our conversation wasn’t that dissimilar to a conversation I had several months later with a Democratic bundler in Brentwood – he’s worth, I’m told, about $US400 million – who was going on about how “the climate and AI are everything” (he thought the former was the end of us, and the latter was our salvation), and how he was “scared shitless about the gender stuff”. When I asked him whether he’d be supporting Biden in 2024, he said, “Of course,” but then he added, “As for the other f..ktards” – he meant younger, more progressive, down-ballot Democrats – “no way, no can do.”

There were other weird signs: the Democratic poll in November showing that the base of the party – including blacks, Latinos, college women and millennials – prefer Trump to Biden; one-time GOP presidential hopeful Nikki Haley saying government shouldn’t bar minors from transitioning; Senator John Fetterman, once lionised by progressives, insisting “I’m not a progressive”, while touting his support for Israel and calling for tougher border controls – prompting Helen Qiu, a Republican who ran unsuccessfully for New York City Council, to call Fetterman a “Christmas miracle”. Compounding confusion about the Great Scramble is the language Americans use to talk about politics – to describe the country they want to live in. “Our language is impoverished, left over from the French Revolution, with us just saying ‘right’ and ‘left’ and what we think we mean by that,” Oklahoma City attorney Jason Reese, who has spent 25 years in GOP politics, tells me. In the 1980s, when he was a kid, Reese was a Reagan Republican. He believed in capitalism, and thought the Soviet Union was evil; he thought the unions, like liberals and high taxes, were a relic. His mum called him “Alex P. Keaton” after the Family Ties character.

But in 1992, just as conservatives were triumphing over everyone – with the USSR now dead, and China and India embracing market economics, and the Democrats, under Bill Clinton, morphing into moderate Republicans – the movement suffered its first shock. So did Reese.

“Ross Perot was the catalyst for this,” he says, referring to the third-party candidate blamed by many Republicans for President George H.W. Bush’s loss to Clinton. “He broke up that old Republican coalition.”

It was Perot who suggested there was a contradiction baked into Reagan’s GOP: while the party embraced free trade and free markets, he argued those policies threatened working-class voters who had recently flocked to it. Perot was especially upset about the North American Free Trade Agreement, which, he said, would lead to a “giant sucking sound going south” – as blue-collar jobs moved from the United States to Mexico. That proved prophetic.

Reese saw the political shift happen in his own extended family, in Kentucky and Texas. In the early 1990s, he says, they cared a lot about abortion. By the 2010s, they were talking non-stop about jobs and immigration. That coloured his own thinking. Today, Reese says, he’s an “economic nationalist” who backs tariffs and a higher minimum wage, and a “foreign policy realist” (meaning, no more wars unless they must be fought), and he’s sceptical of capital punishment.

This confusion also extends to the left, which includes “liberals” and “progressives”, people who believe in minimising economic disparity and people who think talking about economic disparity is racist. Former US president Barack Obama was the “perfect distillation of liberalism,” says Tyler Harper, a comparative literature professor at Bates College who has written on politics and identity, and supported Bernie Sanders’ presidential bid. Progressives, Harper says, are people who think racial identity reigns supreme and have no serious objection to capitalism. “I don’t think they’re left-wing in any substantive sense at all,” he adds. He sees progressivism and “corporatism” as “natural allies”. Exhibit A: the $8 billion that US companies spend yearly on DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) training. “We desperately need a new vocabulary,” he says.

That is how Priyanka Wolan feels – unsure of how to describe herself or what she believes. She moved to the US from India with her family when she was eight, and she has always leaned Democratic. It’s not that she doesn’t know what she believes. She is definitely pro-choice, but she also wants to curb “unauthorised immigration”. She thinks the new gender politics is insane, but she believes strongly in defending civil liberties. And she’s giving her four daughters a home-school education that includes Latin and classical music. The trouble is that all of these things do not fit together into one party, camp or label.

We were having dinner at the house in the hills of Los Angeles that she and her husband, Alan, share with their daughters. My nine-year-old and hers had become friends in an after-school math program. “The present-day conservative movement doesn’t align with my life experience in the way I used to think the Democratic platform did, but the Democratic Party no longer aligns with that either,” Wolan says. “The first time I realised I wasn’t on the left was when I started home-schooling, and people were like, ‘This isn’t supporting public education, what’s wrong with public education?’” she says. “That’s when I started to see, ‘Oh, I’m not falling into line.’”

But then, in 2019, Wolan started to feel the tug of identity politics, and it was like a whirlpool. She and Alan, who is Jewish and 18 years older, had always been “sparring partners”. Now it felt more personal, as if she, a “brown woman”, was facing off against whiteness and the patriarchy.

During the summer of 2020, “it became really difficult for us to have a conversation,” she says. He thought defunding the police was idiotic, and worried about illegal immigration and crime. “I remember saying at one point,” she continues, “‘You know what, let’s not talk politics. You’re never going to understand me, because you’re white, a man, privileged’ – all the jargon.”

She adds: “At one point, I remember my dad saying:

‘You’re not doing a service to yourself or your kids when you’re constantly thinking in terms of your identity. We didn’t come to America for you to think this way.’”

It was other mums who made her rethink things, albeit unwittingly. They didn’t approve of what she was teaching her girls: Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, the poetry of Robert Frost, Mozart sonatas. “At the height of the decolonisation narrative, people would say, ‘Why are you teaching them this? This is the Western canon,’” Wolan, 42, says. She was surprised. She wanted her daughters, as she says, to “have it all” – the most rigorous liberal-arts education that would not only get them into a top college but enable them to think critically.

It wasn’t that her views had changed. She mostly believed in the same things she always had. “I’m liberal in the old sense of the word – the not believing whatever you’re told to believe,” Wolan says. When I ask her whether it is hard being politically homeless, whether it would be easier to join one of the available tribes, she half-smiles and says it isn’t so tough fending off criticisms of home-schooling or deciding who to vote for. The hard thing is getting comfortable with people knowing her husband supported a candidate who everyone she knew thought was evil.

“I didn’t want people knowing he was for Trump,” Wolan says of Alan. “It took me a while to get to the point where I thought, ‘You know what, he’s allowed to have whatever opinions he wants.’”

Brian Lasher, a retired navy commander and high-school history teacher in Erie, Pennsylvania, could not care less whether people know he plans to vote for Trump. Not that he’s excited about it. He thinks Trump’s “an asshole”. But he has to vote – he hasn’t missed an election since he first voted, in 1980 – and he doesn’t believe in voting for protest candidates. He wants his vote to count. (In 1992, he voted for Ross Perot. “That’s a vote I regret,” Lasher says. “Clinton is the best Democratic president of my lifetime.”)

His father came from a family of Calvin Coolidge Republicans – “He refused to have an FDR dime in his pocket” – and his mother was religious and liberal. He was raised Lutheran, and is pro-life, but thinks there needs to be exceptions. He is worried about inflation, and thinks we have to stop illegal immigration (“human trafficking is grotesque”) but he supports legal immigration (“some of the best students I’ve had were immigrants”). He thinks it’s obvious that the poles are warming, but equally obvious that we shouldn’t do away with oil and gas. “That’s just suicidal,” Lasher, 62, says.

During the lockdowns, he watched his students disappear into their screens. The school couldn’t make them turn on their laptop cameras, so almost all turned them off. Usually, he had no idea whether they were even there. Anyway, the “institutional rot” was everywhere, he says, and everything that came out of D.C. reflected as much – not only Covid protocols and deficit spending, but Russiagate, which he calls “bullshit”, and corruption. He means the Clinton emails, the Hunter Biden pay-to-play thing, all of it. If it looks like Robert F. Kennedy Jr, now running for the White House as an independent, might win Pennsylvania, he’ll vote for him. But generally he’s pessimistic about things.

“We’re seeing extremes in both parties drive America toward an abyss,” he says.

He recalls Christmas 2007. He was in Baghdad with the navy, and was at dinner in the mess hall at Saddam Hussein’s old Republican Guard Palace, and General David Petraeus’s chief chaplain was talking about the new “religious reconciliation initiative”. Lasher was asked to be the chaplain’s note-taker, and the pair spent the next six months hopscotching around Baghdad meeting Shiite and Sunni leaders talking about why they hated each other, and what could be done to stem the violence.

“We were at the house of a sheik, a Shiite, he was explaining the differences between Iranian Shiites and Iraqi Shiites.” The sheik said he was going to Iran in three weeks, and asked, “Is there some message you want me to deliver to the Iranians?” Recalls Lasher: “I told him to tell the Iranians that our symbol is the American eagle. In its talon are either arrows or the olive branch. The choice is theirs. ‘Those who live by the sword, die by the sword.’ He responded, ‘Yes! Yes! This is what I have been preaching all my life. I will tell them this.’” Later, after Iraq, after he came home, after the polarisation and anger in America seemed to billow out of control, he would often remember that night in Baghdad, the competing forces.

“We have far more that brings us together than separates us,” he says.

He wants to be hopeful. But those stories, those pieces of the sacred American past, feel far away. People no longer listen to each other, he says. “We’ve tuned each other out.” It’s like everyone is shouting into a Tower of Babel, unaware of who they’re shouting at, or what they’re angry about. “A lot of that, I fault the media for,” he says. “They’re not being honest about the people they report on.”

Rory Fleming, a 23-year-old senior at Yale, agrees that no one really knows who they’re screaming at. “Ever since 2016, it’s been like whiplash,” he tells me. In 2016, he was in high school, he knew a lot of kids from Guatemala, Venezuela and Paraguay, and understood why they felt targeted. He found Trump noxious. But then he got to Yale, which “has been the opposite experience,” Fleming says. “It’s pushed me to the right.” The big thing was Covid, the lockdowns, how the university went all in with masking and shutting down campus life. For Fleming, just like Shelle Lichti, everything came into focus in the summer of 2020. That was when the upside-downness revealed itself.

“I really felt that for the first time in July 2020, when my friend and I took this 45-day, cross-country road trip,” he says. “New York was shut down, and I remember getting to North Dakota, where there were ‘no mask’ signs everywhere. They were reacting against what they felt was authoritarianism, and they weren’t wrong. There was something about the Democratic reaction that was authoritarian.”

Post-whiplash, it was hard to know where he belonged. Fleming believes the government should be spearheading the “green revolution”, starting with renewable projects in places like West Virginia; he is pro-choice, pro-civil liberties, and thinks the US needs to be strong. “That was something I did respect about Trump’s presidency,” Fleming says. “He carried a big stick. We shouldn’t have Houthi rebels with drones firing missiles in the Red Sea. Terrorists should fear the United States, and I don’t think they do right now.”

He recalls his semester abroad, in Dublin, being at a pub with friends, all foreigners, and someone making fun of the US. “I remember saying, ‘You don’t know how lucky you are that it’s us, not China or Russia running the world,” he says. No one argued with that. What’s confusing, Fleming says, is that so many Americans don’t get this.

Lichti agrees. “Politics is so confusing right now,” she says.

This article first appeared in The Free Press

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout