How Snapchat augmented reality at the Louvre

Frustrated by 'people walking by and just giving a quick look over their shoulder as they pass' the museum's top brass has found a revolutionary way to bring its invaluable collection to life.

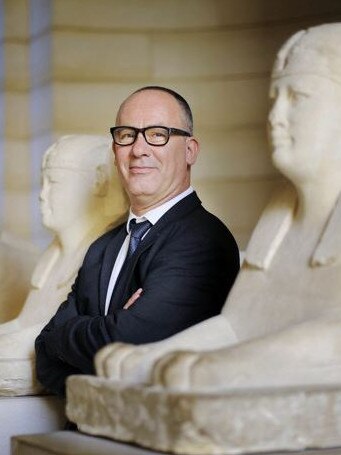

On a mild mid-autumn day, Vincent Rondot, director of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris, is standing in the Cour Carrée, a vast courtyard in the oldest part of the world’s most visited museum. Rondot is besuited, bespectacled and serious-minded, the very picture of an ancient historian. He is holding aloft a smartphone.

On the phone’s camera screen, emerging from the heart of a decommissioned fountain in the Cour Carrée, is a 3D image of the famed Luxor Obelisk. Conjured digitally out of thin air, it reaches for the sky, gold cap flaring in the sun, its towering pillar embellished with hieroglyphs.

This is augmented reality (AR), courtesy of the multimedia messaging app Snapchat. In the most conspicuous example yet of the way AR is shaking up the art world, the cool-kid tech giant has partnered with the centuries-old Louvre to provide an interactive deep dive into its Egyptian treasures. It’s a collision of old and new: visitors to the celebrated art museum scan a QR code, open Snapchat’s camera, and watch ancient stories emerge from the stone, 21st-century tech reanimating the ghosts of early human civilisation.

To the rapt Rondot, it is modern-day sorcery. “I didn’t know the expression before, but this ‘digital overlaid on reality’ is a striking new way to mediate works of art,” he tells The Weekend Australian Magazine during a preview in Paris for the world’s media. “I have no doubt Champollion would have loved to see what he’d dreamed of for the Obelisk, realised in this way through human progress.”

Rondot is referring to the French savant Jean-Pierre Champollion, dubbed the founding father of Egyptology after he solved one of history’s greatest mysteries. In 1822, using the Rosetta Stone, Champollion became the first to decipher Egypt’s hieroglyphics; as a colossal token of thanks, Egyptian ruler Mehemet Ali bestowed upon Paris the (real) Luxor Obelisk. The 250-tonne monolith, sculpted from pink Aswan granite during the reign of Ramses II, was borne up the River Seine on a custom-made barge. Champollion wanted the Obelisk installed outside the Louvre, where he was the inaugural curator of its Egyptian collection. But, after much public debate, King Louis Philippe decreed it be installed in the Place de la Concorde, where today it presides over one of the city’s most emblematic panoramas.

It’s taken 200 years and a few quantum leaps in technology, but Champollion’s original vision is now, in a manner of speaking, a reality.

At 65, Rondot falls outside Snapchat’s target demographic. The 12-year-old platform first made headlines as a sexting app and then was largely used by teens to augment selfies with face filters such as puppy-dog ears and puking rainbows, and to share their location with friends via Snap Maps. In Australia, the app just crossed the eight million monthly users mark and, although it’s commonly associated with Gen Z, Snapchat says 45 per cent of its Australian users are older than 25.

At first, the esteemed Egyptologist admits with a laugh, “we didn’t know at all what we were talking about”. But he’s a realist. No longer do art enthusiasts spend hours contemplating the masterpieces in an attempt to divine profound meaning from the arrangement of brushstrokes. Surveys reveal the average time spent in front of an artwork is 15-30 seconds.

The Mona Lisa, the most famous painting in the world, hangs nearby in the Louvre’s Grand Gallery, where most visitors pause just long enough for a selfie. Heartbreaking for the true art aficionado, but it’s a digitally mediated world and a frenzy of diversions compete for attention. “We have to enter the dance,” Rondot says.

Beyond being au courant, the AR experience gives visitors young and old a reason to linger a moment longer with Rondot’s beloved, millennia-old artefacts. “The key thing with this technology is that it’s not something virtual, it’s not going to the metaverse,” says Helene Guichard, the Egyptian department’s chief curator. “On the contrary, being in the presence of the work, the encounter can be transformative; it can add to your perceptions and understanding.”

Beyond the Great Sphinx of Tanis that guards the entrance to the crypt-like interior of the Louvre’s Department of Egyptian Antiquities, lies a vast display of 6,000 works across two levels. Snapchat’s Paris-based AR Studio chose three of these to “bring to life”, and techs worked closely with the curators over many months, reconstructing missing elements and restoring original pigments using a corpus of archives and references. “Everything you see is scientifically accurate,” says Donatien Bozon, director of the Snapchat studio.

In the first of the key augmented works, original, brilliant colours are digitally restored to the faded bas relief of the Chamber of Ancestors, a carved tomb interior from 1450BC. The famed Dendera Zodiac, a ceiling relief featuring a Ptolemaic sky map from 50BC, is animated and spins in 3D with detailed explanations of its symbols and purpose. At the Naos of Amasis, used by the ancients to harness their gods’ mystical energy, a statue of the god Osiris is virtually reinstated behind the shrine’s digitally restored “gates of heaven”.

“Egypt is understood to be at the origin of everything,” Rondot says. “At the origin of the gods, at the origin of medicine, architecture, you name it.” It’s no accident, he says, that the Louvre’s Egyptian department was chosen to debut the tech: “The civilisation is widely considered at the origin of technology itself.”

In the year since the launch of ChatGPT, advances in generative AI have hogged the headlines and attracted big tech money. But much hype and billions of dollars have already been poured into the future of the so-called “metaverse”, a nebulous, immersive iteration of the internet which mixes virtual reality and augmented reality. With tech giants such as Microsoft and Meta (parent company of Facebook and Instagram) investing heavily in developing ways to interact with the metaverse, and Apple beginning to offer its own take on mixed reality, excitement around the tech has been reinvigorated after a number of false starts.

Augmented reality is, simply, the use of technology to superimpose virtual images, text or audio onto the real world. Unlike virtual reality, which completely replaces reality with a simulated environment, AR merely alters the user’s perception of it. Remember Pokemon Go? The free smartphone game, in which players traversed the physical world trying to catch cartoon creatures, became a worldwide craze in 2016 and introduced AR to the mainstream. The app has been downloaded a billion times. Teens who’ve grown up online shrug at it, but for those born before the advent of the smartphone, the technology can appear – as it did to Rondot – as if conjured from the future.

“The curators of the ancient Egypt department were very moved when they tried the AR for the first time,” Bozon says. “For them, it was just like they had entered an Egyptian temple for the first time, thousands of years ago.”

Bozon is a jeans-and-sneakers guy, a punk music aficionado who is evangelical about the potential for augmented reality to “improve the way people learn and interact with the world, especially in the field of culture and the arts”. We are standing before the Chamber of Ancestors, his favourite of the four location-specific AR experiences. Those lucky enough to visit the Louvre before Egypt Augmented winds up late next year can enjoy these encounters IRL, as the kids say. Meanwhile, Snapchat users around the globe can access a Face Lens feature through their smartphone that allows them to “wear” ancient Egyptian funerary masks.

“The Chamber of Ancestors is the most ancient piece of art that we augment,” Bozon says. “As you can see, time has passed and it’s pretty damaged; you cannot really see the drawings any more, or the colours. People tend to forget hieroglyphs were super colourful back in the day.”

Does the Louvre really need enhancing, I wonder aloud. After all, it’s the most famous museum in the world, its great glass pyramid a global symbol for priceless art. “When we first discussed this with the team at the museum, they told us they had challenges trying to explain the works of art, especially the antiquities, to the public,” Bozon says. “Not only the young public but overall, they see people walking by and just giving a quick look over their shoulder as they pass. It is very frustrating for them because these pieces of art are invaluable; they wanted a new way to explain the story behind them.”

Everyone has a smartphone in their pocket; the app is free and you don’t need to wear a special headset, he says. “It’s a very useful cultural mediation tool and a lot of museums are thinking about that right now.”

Sebastian Chan, director and CEO of the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), is a highly respected figure in Australia’s museum and gallery scene. He says museums worldwide have been under heightened pressure to stay relevant as digital content multiplies and attention spans contract. “Museums themselves have become media platforms, media brands,” he says. Globally recognised spaces such as the Louvre, the Smithsonian and the British Museum, for example, are “like the Nikes or Reeboks of museums. And so this sort of brand partnership, particularly with technology companies, has become a way of achieving, in the museum’s mind, a sense of staying [contemporary].” The relationship is a symbiotic one. “Because museums have such a trusted position in society, the association gives companies like Snapchat an aura of respectability and permanence,” he says.

Not that long ago it was common to see signs banning photography in gallery spaces. “That’s old-guard thinking now, like the stereotype of librarians telling people to shush in the library,” he says. “I was working in museums at the time and the shift was very quick. It went from ‘You can’t take photos’, then the smartphone came out, and within two years people were being encouraged: ‘Take photos! Share them with your friends!’ The phone became such an important part of how visitors experienced things.”

Artists have long been at the forefront of emerging technologies. Chan points to the work of Melbourne artist Jeffrey Shaw, regarded as one of the international pioneers of computer art. His new-media work Virtual Sculptures married computer-generated graphics with illusion techniques borrowed from the theatre to create the impression of objects floating in space. It was exhibited in Amsterdam in 1981. Museums, though traditionally a little less nimble, have been experimenting with different types of media, “from the early days of radio and audio guides to CD-ROMs and the internet”, Chan says.

To date, members of the wider public have proved reluctant to wear things on their faces when interacting with an altered reality. But the embrace of app-based AR is just the latest in a continuum whose logical next step will involve more immersive tech such as Snap’s as-yet-unreleased AR version of its Spectacles and mixed reality headsets such as the Apple Vision Pro, out next year.

Snapchat has 750 million monthly users globally, according to company data. Of those, about 250 million engage with AR, loading six billion AR experiences a day. The company launched its AR feature (called Lenses) in 2015 and has been steadily building it out beyond the frivolity of funny-face filters in an effort to capture a broader demographic. The high-profile Louvre collaboration is the latest salvo in its fight for supremacy in the AR space.

“The silly, fun stuff is just one facet of this technology,” Bozon says. It can be used to scan wine labels for reviews and prices, to identify songs, plants or food and, increasingly, for AR shopping and virtual try-on experiences. Parent company Snap has begun easing people into the idea of AR as an unobtrusive add-on to the real world. At its recent developer conference, AR filters were integrated into concert and festival apps as well as cameras broadcasting live sporting events. Snap has also developed a full-size AR mirror, which applies visual effects much like a smartphone. The mirror, which allows shoppers to see how they look in an article of clothing without physically trying it on, is being trialled at retail stores in the US.

“We are also evolving day by day toward more cultural and educational uses and opening up a whole new range of possibilities, especially with cultural institutions,” Bozon says. To that end, Snapchat opened its dedicated AR studio at the beginning of last year, based out of the world’s biggest startup campus, Station F, in Paris’ 13th arrondissement. “Paris was a good match because the cultural scene is large and has a big echo in the world,” says studio manager Antoine Gilbert during a brief tour of the business incubator that’s home to more than 1000 startups. “Also, there is a vibrant ecosystem for AR already here.” The 34,000sqm space is built within the skeleton of a former rail freight depot and retains its industrial character, with the original concrete floors and shipping containers transformed into meeting rooms. Tucked away amid the photogenic playground of snack-filled micro-kitchens and the obligatory pinball machines is an image of Snapchat’s familiar yellow ghost icon, behind which a couple of dozen employees are busy working on the future. One of Snapchat’s full-size AR mirrors provides endless amusement for visitors, a procession of whom stand before it and variously morph into versions of Na’vi from the movie Avatar or, less geekily, Beyonce in her Sasha Fierce era.

Various institutions have taken an interest in Snapchat’s technology. Last year, the company partnered with the French National Library to create a time-travelling experience in which the building’s façade was overlaid with old-timey effects. It also teamed with artist Christian Marclay to transform Paris’s Centre Pompidou into a giant, multi-coloured AR musical instrument.

Other collaborations range from the painfully hip – uniting with electronic duo Daft Punk to create a series of AR experiences celebrating the 10th-anniversary edition of its Random Access Memories album – to the progressive and educational.

On International Women’s Day earlier this year, Snapchat paid homage to female icons such as Simone Veil and Josephine Baker by using AR to show them alongside the many existing statues of famous French men. Last year, Australia played host to a more commercial application when Prime Video Australia used Snapchat’s AR to promote The Lord of the Rings: Rings of Power on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

One of the key uses for AR is e-commerce, and luxury brands are climbing aboard the bandwagon, to the extent that Snap has appointed a global head of luxury. Recently, Louis Vuitton applied Snapchat’s AR features to its new collaboration with Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama: users point their camera at global landmarks including the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty to see them come to life with the artist’s signature colourful dots. Cartier, too, used Snapchat AR to launch the fourth iteration of its Tank Watch in February, allowing users to virtually try on the iconic timepiece.

Snap sees AR as “a very human way of accessing technology” and, as the perception of it moves from a toy towards a utility, Bozon predicts the tech will continue its march into the mainstream in 2024. Just as the telephone was not taken seriously upon its patenting in 1876 – the telegraph was working just fine – so too will people eventually embrace this new reality. “With AR technology, the world becomes a canvas,” he says. “And then you can do whatever you want.”

Egypt Augmented is at the Louvre in Paris until October 2024

How AR works (and plays)

Unlike virtual reality, which requires a headset, you can access the world of augmented reality with just a smartphone. With an AR collaboration, digital pictures and text are overlaid onto whatever you’ve pointed your phone at. Seen memojis or digital avatars on your phone? You’ve probably watched entry-level AR at work. Now AR is also used in design, education, media, culture and the workplace.

Social platforms: The Evolution

Snapchat

Run by Evan Spiegel

750 million monthly users

Known for funny filters, Snap Map, disappearing messages. Evolving AR

Run by Mark Zuckerberg (Meta)

2.35 billion monthly users

Sharing photos and videos. Evolving ‘influencers’ businesses.

Run by Zuckerberg again (Meta),

3 billion monthly users

Messenger app, family/friend updates, “newsfeed”. Evolving the metaverse

Tiktok

Run by Chinese company ByteDance

1.1 billion monthly users

Short viral videos, most popular with Gen Z audience. Evolving news and entertainment

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout