The remarkable life and wisdom of Riverbank Frank

He was once an angry, whitefella-hating revolutionary. Now, Riverbank Frank Doolan is a beacon of forgiveness and love | WATCH

It was late at night last October when Steve Lawrence, the former mayor of Dubbo, now in the NSW upper house, posted an appeal on GoFundMe for his old mate Riverbank Frank Doolan, “local Wiradjuri elder, poet, champion of equality and reconciliation, and well-known Dubbo legend”.

For the past 20 or so years Riverbank Frank has lived alone in the scrub, bunking down in an old caravan with no electricity. His camp is a few kilometres out of Dubbo on the stock route where cockatoos complain from gnarly rivergums. The Macquarie River slithers across his front yard. Out the back, road trains groan down the Newell Highway. He shares a campfire with his cattle dog, Reg, and a couple of scraggy cats. Other than books, his possessions tally up to bugger all.

As Lawrence noted, it’s rare for Riverbank to ask for help. He’s usually the one digging into his pockets for others in the Dubbo community. Someone once gave him a car and a few weeks later they saw a troubled single mum with a mob of kids driving it around. Riverbank reckoned she needed it more than an old blackfella with two good legs. Besides, someone always stops to give him a lift.

But his caravan was busted and leaking, and so Lawrence put out a call; he wanted to raise 15 grand to buy Riverbank a decent second-hand van. The response was astounding. At 8.23am the following day Lawrenece texted me: “$5250 in less than 12 hours! The man is loved!” By 9.35am the figure was $8,490. One donation was for $500; the accompanying post says: “Riverbank Frank is a source of wisdom, counsel, humour, empathy and advice. He’s been a great friend.” The next morning the tally was $16,452 and the appeal was closed before Riverbank got rich, ’cause that would be awkward.

The man is certainly loved. To encounter Riverbank is to be enriched. He talks in pictures. He draws people in with yarns and humour. He connects the underclass to the nation’s mainstream. He brings black to white and white to black with an uncanny ability, says a colleague, to pop up “under the right coolabah tree at the right time” when bad things are getting worse in some poor bugger’s life. “Brother,” Riverbank says with a giggle. “You know you’ve really made the big time when you turn up at the mental health unit at Dubbo Base [to check on someone in distress] and all the patients greet you by name.”

It wasn’t always like this. For a long time Riverbank was angry. A hard-drinking university dropout, he became a leader to his people and now seems to pop up when he’s needed. When Covid first ran rampant in the black community in Dubbo, he was pictured on the front page of The Australian getting his jab, encouraging others. The story highlighted the difficulties his mob faced getting the vaccine – having the documentation and an email address – even as then PM Scott Morrison came out grinning: “How good is Riverbank Frank!”

He’s dedicated his life to closing gaps. Endlessly striving to improve the lot of his mob, to get them working in good jobs and living in decent homes. His heart aches at the appalling rates of black incarceration. He despairs at the health of his kin, dying, disgracefully, decades before the rest of us. But he lives with hope.

And Riverbank Frank has a dream.

“I believe in this country and its people, not just my people,” he says.

“I think most fair-minded people want to see more of a working relationship between blacks and whites. We all want better outcomes… We are kidding ourselves if we believe – and I’m speaking as an Indigenous man – that we are the font of all knowledge in this country. We’ve gotta get over ourselves and realise that the best way forward is to learn from each other.”

“It’s time we all put away our mobile phones, lit a campfire and had a bit of a yarn to each other… Brother, just imagine what could be achieved if we all worked together.”

“He’s a God-filled man, my brother Frank… he walks the truth,” says journalist Stan Grant, who was at uni in Bathurst with him. Grant’s praise is profound, as Riverbank was opposed to the voice to parliament (defeated in last year’s referendum); Grant supported it.

“He’s so forward in his thinking,” says Peter McKenna, the former boss-cop at Dubbo who’s now an Assistant Commissioner in charge of Northern NSW. “He has a lot of wisdom and he’s always looking for ways to improve things… he showed us as police how we could do things better, just by listening and showing respect.”

Frank Doolan was born on the Aborigines Protection Board reserve on the outskirts of the outback town of Bourke in 1961. The mission was on the banks of the Darling River, on the wrong side of the levee that protected the houses of the white folk in town when it flooded.

His father Terry worked as a labourer at the meat works and on the council, while his mother, Pat, got a teaching diploma. She worked as a teacher’s aid after their five kids (Frank being the second oldest) had finished school. His parents were good, solid people, he says, who pushed their kids to be educated.

One of his favourite early memories was listening to the wireless with his father one night. “It was a magic moment ’cause [Indigenous boxer] Lionel Rose was winning the world title,” he says. “Man, we had nothin’, but I was sitting with my father, listening to every punch, duckin’ and weavin’, and we were dancin’. I knew my father loved me. We were world champions that night. We had the best left hook on the planet.” Before that he’d never seen an Aborigine celebrated for an achievement. “Before that, there was only shame.”

Frank was four when Charlie Perkins and his freedom riders swept through NSW advocating for black rights. The bus never made it to Bourke, but the entire mob followed its movements with great excitement as it travelled to their sister missions in Moree and Walgett. “No one knew what a freedom ride was, they just knew they were supporting blackfellas,” he says. It was talked about for years. “To us, it was [as astonishing as] the landing on the Moon.”

He grew up in the time of the awakening when for the first time Aborigines had an inkling that they had rights and that things could be different. But change was slow. Racism ran deep. “From an early age I always knew I was black… there were [white] kids that I was good friends with at school but I never entertained the thought of going around to their place after school. There were unspoken rules.”

In 1956 there had been an infamous death in the Bourke police cells. Charles “Boonie” Hilt, a 36-year-old Aboriginal shearer, was arrested on Anzac Day for being drunk after playing two-up at the Royal Hotel. He died in agony a couple of days later from “shock, haemorrhage and peritonitis following a rupture of the small bowel”. The police said they “accidentally” fell on him as they manhandled him into the cells.

Riverbank’s father told him that story often, and from an early age. It was told as a cautionary tale, that you could be kicked to death for being black. “It was a story about not being too confident,” he says. “Or to take the cops lightly.”

While he was topping his classes at school – and the only black student in most of them – he was constantly at war with the principal. For his final two years he was sent to Kirinari Hostel in Sydney, a place for bright Indigenous kids to further their education. He loved it. “I was with all these blackfellas from all over NSW and I realised there was strength in numbers,” he says. The great rugby league five-eighth, Cliffy Lyons, was a classmate and a friend.

It was in these final school years that he found his way to the radical black politics of Redfern. “The ’Fern then, man it was rockin’,” he says. “Any self-respectin’ blackfella, that’s where they went. This was ’76, ’77. Lyall Munro, Billy Craigie, Cecil Patten, Bob Bellear, Sol Bellear, Paul Coe… they were all in Redfern.”

He was soaking it all in, going to protests and fighting whitefellas. “Sometimes I’d get a floggin’, but usually it was OK if I got the first hit in.” They all dreamed of revolution. “None of us were looking for the middle ground,” he says.

Looking back, he reckons the leadership was pretty hopeless. “They had a brains trust – they had one [brain] and were handin’ it around,” he says. He cites, by way of example, black activist Michael Mansell’s trip to Libya. “How long did he stay up to think of that!” he says. “Going off to see Gaddafi about human rights!”

His final gesture on finishing school was an act of defiance: “The night after the final exams, I hoisted my scungies up the flagpole.” Despite himself, he did well in his exams and got the marks to get into journalism at Mitchell College, Bathurst. He deferred for a few years.

Professor Gillian Cowlishaw, an anthropologist, was then a lecturer in Indigenous studies at Bathurst. She’d met Frank in Bourke when he was a young man playing protest songs on the local radio station. “He had read Kevin Gilbert [the Indigenous author, activist, poet and artist] and [Gilbert] was his main inspiration,” she says. “Frank was angry, but he was also thoughtful… but in those days he didn’t know who he was. He smoked a lot of dope and he drank a lot of grog.”

When he turned up at university in Bathurst, a few years later, people wanted to know him, she says, because “he was such a livewire”. But Cowlishaw says he was attuned to those who “showed off their friendliness” towards Aboriginal people and would cut them down with a witty remark. She has no idea what sort of student he was, because “he never handed in any work”. He left after a year. He wanted to write poetry and stories, he didn’t want to report.

Cowlishaw would go on to marry the great social justice lawyer Hal Wootten, one of the commissioners who led the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. He and Frank became good friends. Says Frank: “Hal used to look at me and say, ‘Riverbank, you need a plan.’ And I’d say: ‘We’ve got a plan, man. We plan to overthrow you whitefellas’. And Hal would say, ‘Yeah, then what?’ And he was dead right. Only a fool would want to tear down the system when you haven’t got a better system to replace it with. Old Hal was a wise man.”

Riverbank gleaned all he could from intellectuals like Wootten, but it was his father who taught him what he says is the greatest gift, the power of forgiveness.

Not long before his father’s death, Frank was chatting to him about his life. Terry mentioned he’d spent time at Albion Street, a staging post for black kids removed from their families. Frank pressed him for details. “Eventually he said, ‘I was one of the Stolen Generation.’ You should have seen little old reactionary me, it was as if it had happened to me. I was livid.” Terry recalled having a row with the superintendent at Albion Street. His sister had died in Bourke and he wanted to go home for her funeral. The superintendent put him on 14 days of bread and water for dissent. He was nine years old.

Through tears, then and now, Riverbank asked his father how he felt having been treated like that. “Well, I forgive ’em, son,” the old man said. “I’m a Christian. I forgive ’em.’’ It struck Frank like a body blow. “My father had suffered great deprivations and yet he had the ability to look inside and find what it took to let go.”

Riverbank, too, has had to make peace with his demons. In his early twenties he fell in love with a white woman of Yugoslavian origin; she moved with him to Bourke where their daughter, Rebecca Stoyko, was born in 1980. “I was 24, goin’ on 16,” he says of fatherhood. “I was a typical bloke, I had it all but I wanted more. Man, if I could take back those times…” Frank played the field. His partner left Bourke with Rebecca when she was two and half. “Her mum made attempts to get me to be a father of responsibility, and in the end, I just didn’t do that,” he admits with shame.

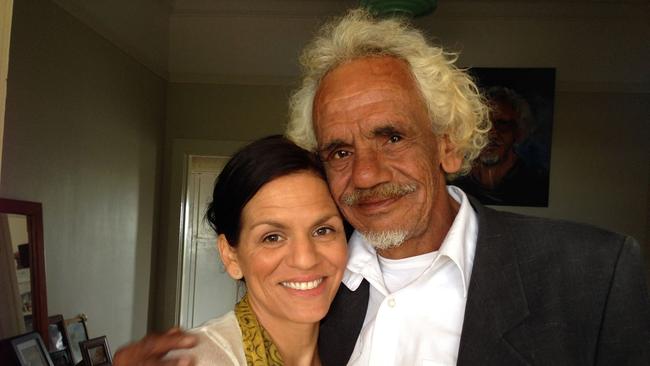

He lost touch with Rebecca until she made contact as an adult with children of her own. “I grew up without my father,” Rebecca says. “It was not until I was in my thirties that we really reconnected… he visited my house on the Northern Rivers and he camped out in the backyard.” They talked it out, around the campfire. She expressed her anger and resentment. He acknowledged the pain he had caused and the shame he felt. She forgave him.

“She’s my pride and joy,” says Riverbank. “There were times when she would have ached for her father to be around, and I wasn’t there. She could have just said, ‘I don’t need you in my life,’ but she doesn’t say that.”

She recalls seeing him on the television news, an angry black man at protests. “When I got to know him he wasn’t that person anymore.” She says their relationship is now “very much a picture of reconciliation. In spite of the things that happened, there’s peace…I feel very loved by my father, and I feel no anger.”

Her grandfather, Terry, was a lay preacher who delivered sermons by the Darling. Rebecca says those principles, ingrained in her father from an early age, fuel the work he does now.

As is his way, Riverbank tells me a yarn to explain his outlook. In the early 2000s, he went to an Indigenous conference where they talked about the need to set up Indigenous men’s sheds. He thought this exclusivity was “bullshit” so he went home and worked to set up the Dubbo Community Men’s Shed, for everyone. It opened in 2007 with a logo of a black hand shaking a white hand. It’s been a great success.

The shed was sponsored by a local Christian group, and a couple of its members reckoned that gave them the right to proselytise to the other blokes. “These were guys with depression and prostate cancer, they didn’t need someone by their side badgering them about whether or not they believed in Jesus Christ,” Riverbank says. He pulled the evangelists aside and said, “Brothers, don’t talk Jesus, be Jesus. You can talk all this religiosity, or you can be in the marketplace and with the people.”

Riverbank’s place is with the broken people. “I don’t shout my faith from the rooftops, but I’m not ashamed of what I believe,” he says, “But in saying that, I’m not closed off to other ideas or other faiths. I’m not bigoted in what I believe. And I’m not naive to the way the church has been a nightmare and a failure to many Indigenous Australians.”

He later sends me a text: “Brother, Google Kev Carmody’s Comrade Jesus Christ to get my take on Christianity.”

You see / He’d stand with the downtrodden masses / Identify with the weak and oppressed / He’d condemn the hypocrites in church pews / And the affluent, arrogant West… He’d mix with prostitutes and sinners / Challenge all to cast the first stone / A compassionate agitator / One of the greatest the world has known.

In the early ’90s, Riverbank drifted from Redfern out to Mt Druitt in Sydney’s west, and found his way to the Holy Family Parish. “It wasn’t actually a church, it was a community,” says the now retired priest Father Paul Hanna, who ran it. There was a food collective that sold cheap groceries. It was a drop-in centre for the community. It took on people on court-mandated community service orders, rather than seeing them jailed. It was big on service and small on sermons. “The R word wasn’t religion, it was relationships,” says Hanna. “Riverbank just sort of turned up one day and stayed.”

He needed somewhere to live and there was a dilapidated old house that had been moved onto the church grounds that they hadn’t got around to renovating. Riverbank lived in this run-down house for much of the ’90s, working among the poor in Australia’s largest public housing estate with its large Koori and migrant population. It was in Mt Druitt, not long after arriving, that Riverbank took his last swig of grog and stubbed his final joint. There was too much to do and he needed a clear head to do it.

“Riverbank has the most extraordinary ability to connect with the people from the edges,” Hanna says. “We’d see people when they were at their lowest. There was a team of people to help them and Riverbank would ride shotgun.” He’d turn up at court to plead with judges to spare someone from jail. He’d argue passionately, because he knew the family and knew the desperate circumstances they’d come from. He’d arrive at a grieving house where someone’s kid had suicided, or died of an overdose, and help to arrange a funeral that he’d then be called on to speak at.

Riverbank knew all the leaders of all the communities – the Tongans, the Lebanese, the Samoans, the Vietnamese… and, of course, the Kooris. If a Koori had murdered a Tongan, he’d bring the community leaders together to quell the tensions. “They all had incredible respect for Riverbank because he lived very simply,” says Hanna. “He, too, lived on the edge.”

Riverbank says Hanna was his greatest teacher. “I saw in that little Lebanese man someone who was actually trying to hold up what the Catholic faith should be. He did community and it was a marvellous thing to watch. He taught me the value of stories, the idea that everybody has a story and that every story matters. He never lectured, he taught me through the power of example… I am forever changed for having known him.”

And then in the early 2000s, Riverbank was drawn back to his Wiradjuri country, to Dubbo, to work among his mob. “He needed to heal,” and to let go of his anger, says his sister, Ellen, a health worker who lives in Condobolin. “And the river helped him.” He sat on the banks of the Macquarie, listening to the galahs and the cockatoos, and he realised something profound. He was racist. Deep down, he’d hated white people all his life. “I didn’t want to be that person,” he says.

And so he forgave the cops who bashed Boonie Hilt. He forgave the authorities who stole his father. He forgave himself for abandoning his daughter. He bundled it all up, chucked it in the river and it flowed away downstream, until all that bitterness had dissipated somewhere out in the ocean.

Dubbo’s Apollo Estate is a place locals call the Bronx. Riverbank works at an innovative youth project there called LeaderLife. Its aim is to break the cycle of despair. Part of the program is modelled on the groundbreaking youth program in Armidale, BackTrack, run by Bernie Shakeshaft. “The kids at the Apollo Estate, they gave me the name Riverbank,” he says. “They used to call me Missoman when I was living on the mission and then I moved to the river. I would tell the kids I’d moved from the mission to riverbank, so I became Riverbank, and it stuck. And rivers features heavily in our story – anywhere there’s life in Australia is near a river.”

In 2019, Riverbank had been pivotal in convincing the then Dubbo police chief, Peter McKenna, to initiate the brave and successful Project Walwaay. Instead of locking black kids up, it led to a dramatic reduction in youth crime by having a dedicated team of police working with the most prolific offenders. They played in a touch-footy team with them; they opened up the PCYC and the swimming pool on Friday and bussed in kids from the housing estates for sausages sizzles. Youth crime, previously at its worst on those two nights, was becalmed.

McKenna says Riverbank was able to explain to the Indigenous community why the program was important. “He gave us legitimacy,” says McKenna, who is looking to roll out programs similar to Walwaay in indigenous communities around NSW.

And yet Riverbank vehemently opposed the voice. It would have been a waste of money, he says. “It would have become another ATSIC [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission], a bureaucracy based on political trickery… We have enough organisations, more than enough now, and what I’m saying is rather than reinvent the wheel, the existing infrastructure is there. Let’s tweak it and make it more efficient and make people more accountable. Let’s work together and make what we have work better.”

He adds: “A race-based system to me is not the solution. I am Australian and I believe in this place and our ability to settle our differences and to go forward as one people. We’ve got to learn to listen to each other, to forge a new path together… we’ve got it all wrong [if we] think that the rights come first, we’ve got to build the relationship… we’ve got to stop demonising each other, the black man and the white.”

Stan Grant, although a voice supporter, says he can see why Riverbank opposed it. “I think it’s very consistent [with his approach],” he says. “It comes from an acknowledgement that politics is never going to do it. He lives very close to the ground and he says, ‘I don’t want political answers from Canberra’.”

Riverbank, despite his opposition to the voice, scoffs at Jacinta Nampijinpa Price’s comment during her National Press Club appearance ahead of the referendum that “there are no ongoing negative impacts of colonialism”. He lives amongst the consequences of it every day. “Man, that was a stupid thing to say,” he says. “She pulled that one out of her arse.”

How does he feel about Australia Day being celebrated on January 26? “I don’t have a problem with it... I just feel that if we [as Indigenous people] want people to respect our ceremonies, we need to do likewise. What’s the point of changing the date? Why upset people? Everybody knows the history and we are all diminished by it, but at the end of the day that’s all it is, history. It can’t reach out from the past and hurt us unless we allow it to. I can understand that people do have a problem with it and want to politicise the date, but I think it’s a tired old argument and I think our children will work things out in a different way.”

His title at the LeaderLife program in Dubbo is Indigenous Elder and Community Worker, but manager Joh Leader laughs when I ask what Riverbank’s job description is. He doesn’t have one, she says, and yet he’s vital to the success of the program. He’s the great connector, linking the program with people it needs to be successful.

She says he has an almost freakish knack for dealing with trauma or mayhem. “We might be having a tough day with a young fella and he’ll just sweep in, tell him a yarn and bring it all into perspective for this young person.” He has, she says, “incredibly forward thinking views” about what’s needed to set kids up for success and to break the cycle of dysfunction.

And for that to happen, he says, communities need grassroots programs like Leaderlife and BackTrack and for those programs to have the backing of all the other institutions and the community – schools, police, hospitals, prisons, the business community, farmers… If, in a place like Dubbo, you can get all of these things humming along together, great change can be made.

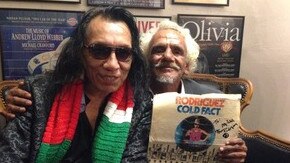

As a young man, the first album Riverbank listened to that wasn’t full of black protest songs was “Sugar Man” Rodriguez’s Cold Fact. When he read that Rodriguez was touring Australia in 2015, a friend in the music game arranged for him to meet with the singer backstage. The pair hit it off.

The following year, when Rodreguez toured again, he invited Riverbank to Sydney. He stayed in a flash hotel and he and Rodriguez hung out. Rodriguez invited him to appear at his concerts and so Riverbank found himself on stage – wedged between Archie Roach and Rodrigeuz – with 15 minutes, a microphone and an audience of thousands for five concerts at the State Theatre and two more at the Enmore.

Rodriguez said he could use the platform to talk about whatever he wanted. Riverbank chose to talk about refugees locked up in Villawood. For years he’d protested about their detention, particularly children, and was annoyed it was an issue the Indigenous leadership hadn’t taken up. “I watch NITV and I read the papers and I don’t see any of the black leaders speakin’ up on their behalf,” he told the audience. “And that’s a real shame…cause I’m old enough as an Aboriginal person to know what it is to be stateless, I was born before ’67.”

Rodrigeuz asked Riverbank if he’d accompany him on the rest of the tour of Australia, and possibly overseas. Riverbank told him he had to get back to Dubbo. There were things to do and black and whitefellas to meet.

A farmer friend heard about Riverbank’s need for a caravan. He’s got an old van in his shed and Riverbank says he’ll probably use this in the interim. He reckons that he can probably buy a ‘really good’ second hand van for $5000 and that he’ll give the rest of the $16,452 to charity. b

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout