How policing broke a strongman

He was Australia’s strongest man, literally pulling planes and trains behind him. But brute force wouldn’t help Grant Edwards through this.

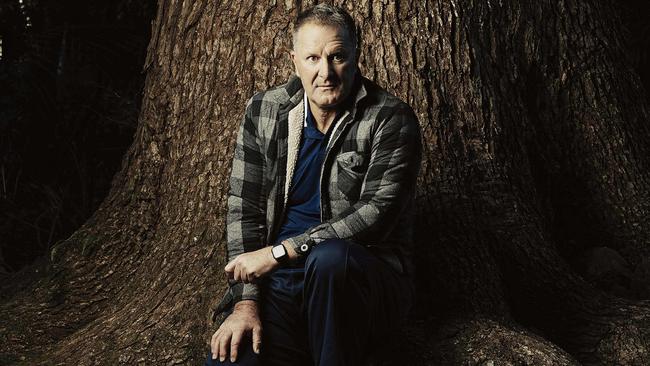

He is waiting at an inner city cafe, broad-shouldered and solid, taking up more space than he probably imagines. His wide back faces the door, his thin black jacket a statement of defiance against the cold; his thick hands clasp a cup of decaffeinated coffee.

Outwardly, he is the embodiment of strength. He was officially recognised as Australia’s strongest man for several years in the 1990s, and through his various public feats of super-strength — pulling planes and trains single-handedly — he has been synonymous with this image for even longer. Yet there is a sense of vulnerability as Grant Edwards seats himself on this weekday morning in Sydney. “I normally sit there,” he admits when pressed about a seemingly minor reference in his new book, and signals the chair opposite abutting a solid wall. “If you ever go anywhere with a bunch of coppers, there’s a rush to sit there.”

At 56, Edwards has spent much of his life with his back to the wall, or covering it. As a long-serving officer with the Australian Federal Police, his working days have exposed him to many of the worst elements of society, from child exploitation to human trafficking. It’s also a suitable metaphor for the life that led him to this career, and his ability to endure a tumultuous family life.

The cumulative effects of both have brought him here today. But even as he is readying to talk about the life story he has penned — part strength, part endurance — another piece of his mind is focused on the lingering effects of the years of trauma. Which is why he has chosen to sit facing the wall for a change. Unable to scan the room, as he has instinctively done for so long, or to see what is happening on the street, today he is trying instead to lessen the hyper-vigilance that once seemed to fortify him.

For much of his adult life, strength in its various guises has been one of his defining features. But it is brute force that has marked him most. A saviour and a scourge. “When you go into physical training you can block everything out. You don’t have anything going through your head that’s negative,” he says plainly. “I now know that’s how I survived.”

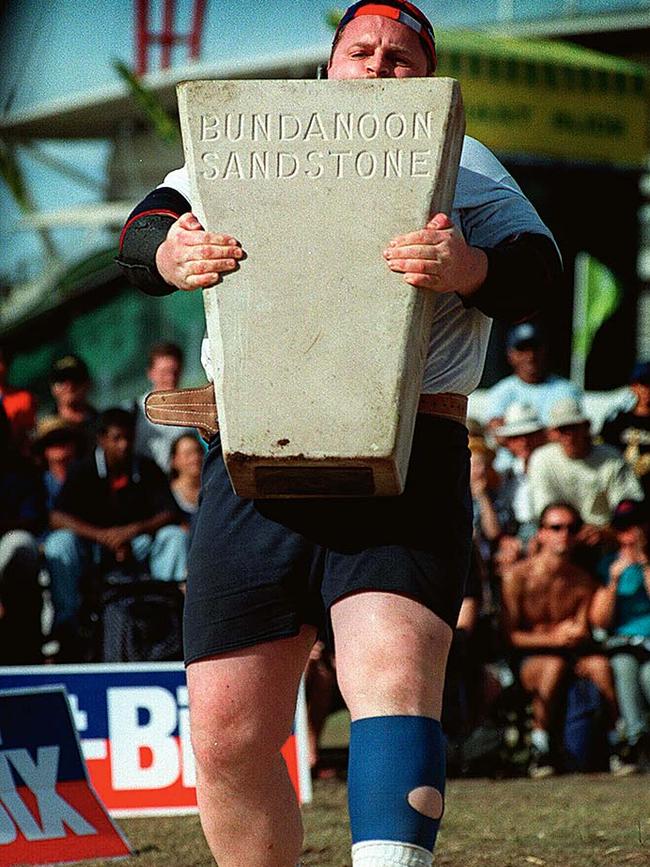

Not many people can single-handedly pull an airplane. Grant Edwards has tugged several, civilian and commercial. He has also pulled a train engine, moving it a mighty 36.8m to land him in the Guinness Book of Records; his eclectic list includes a tram and an almost 400-tonne ship.

“A lot of it is up here,” he says, pointing to his temple as he outlines some of the finer points of pulling a plane: attention to weight distribution, ensuring tyres are inflated to the maximum, and heeding the advice of an Icelandic strongman that a stationary vehicle will respond more favourably to a gentle touch. “You’ve always got that fear of not being able to move it,” says Edwards. “You’ve got to go through that pain barrier.”

That he has been able to surmount both fear and pain is testament to the unexpected strengths he discovered as his childhood began to unravel. He has few memories of his earliest years in Sydney’s south-west. The clearest is when he was nine and his father Ray left him, his younger sister Jenelle and his mother Denise to live with his boyfriend. In early 1970s Sydney, the news sent the family into a tailspin. His mother, who would later work as a bookkeeper and in an abattoir, found solace in alcohol and the company of violent gang members who would shoot up heroin in the lounge room.

While Edwards would later reconcile with his father, in his immediate absence his maternal grandfather became his role model. A year later, when Edwards was 10, his grandfather suicided.

With his mother increasingly volatile, and constantly moving houses with her children, he was forced to look elsewhere for emotional sustenance. Always big — he was 1.7m on his 11th birthday — he was encouraged to play rugby but disliked the aggression. Instead, at 14 he started lifting weights at a YMCA gym and later, at the suggestion of his PE teacher — Olympic decathlete Peter Hadfield — he took up shot put. On the cusp of adulthood he found a way to release the stresses of his home life, and, at least physically, he thrived. By 1996, he was officially Australia’s Strongest Man, a title he held for four years.

As an amateur strongman, Edwards found a sense of calmness. “Nothing cleared my head quite like hitting the gym and heaving heavy metal.” His physique opened many sporting doors. He competed in an international shot put event. He landed a scholarship to play gridiron in Hawaii but reluctantly returned home after a year at his mother’s urging. He even qualified to represent Australia in bobsleigh at the 1992 winter Olympics, although his team ultimately was not selected.

The costs of exercising his immense power were significant. At the peak of his strongman reign he was eating 6000 calories across 11 meals a day, including four cans of creamed rice. Soon he could not even fit into his car, and he developed a litany of injuries: a shattered ankle (after dropping a 200kg block of sandstone during a competition), a lateral tear of his Achilles tendon, a lost chunk of his right pectoral, a torn quadriceps muscle, multiple hamstring tears and three herniated discs.

But perhaps the greatest setback was to his intended career. While he had tried several jobs, from bouncer to barman, he really wanted to become a police officer. His great-great-uncle Arthur Loftus “Lofty” Steele had apprehended Ned Kelly at Glenrowan in 1880; two of his uncles were also in the force. Edwards did not find it easy to join the police. Because his weight had risen so sharply as part of his strongman regimen — he peaked at 160kg and had to weigh himself on scales used to calculate freight at the post office — he was deemed too heavy. A sympathetic recruiting officer at the AFP kept his hopes alive on the proviso he could lower his weight. Eventually he did and in August 1985 he finally joined the force.

He loved policing immediately. But it was also one of the most emotionally brutal vocations. “No one,” he says, “ever tells you that you are going to get exposure to somewhere near 200 traumatic events in a career, let alone how you deal with that.” For a long time he did not question the horrors he witnessed at work as he progressed through the fraud and drug squads to internal investigations and ultimately to scrutinising sexual abuse and human trafficking, spending countless hours viewing child exploitation footage.

As one of 80,000 full-time emergency workers in Australia, exposure to trauma was an accepted part of his job. “If you’re in my line of work, it’s not unreasonable to expect to be verbally abused, physically assaulted, spat at, bitten or have urine thrown at you,” he writes. “You’ll witness the devastation of natural disasters. You’ll remove children from dysfunctional families and be outraged to see they’re covered in welts and sores from living in flea-infested, maggot-riddled homes where the stench and filth offends your senses. You may be required to be present in an operating theatre while surgeons fight to save the life of a drug courier whose gut is full of illicit drugs worth enough money to buy a two-storey house in an exclusive Sydney suburb. You might attend a scene where the friends of a deceased person were so stoned they used the electric cord from an iron to try to jump-start his heart when he stopped breathing…

“Any young person wanting to join the Federal Police should realise it’s guaranteed their hearts will shatter if they’re called upon to investigate the horror of toddlers being sexually assaulted. God knows you’ll be consumed by a rage that makes your body shake and forces tears from your eyes.”

Yet for a long time he did not stop to consider the cumulative effects of this work, the “terrible realities [that] are the ‘pebbles’ that police constantly add to the invisible backpack we carry. Over time, you realise the pack is heavy but you soldier on. You only realise the devastating effect of your journey when the day comes that you’re unable to carry the load anymore”.

For Grant Edwards, that day took decades to materialise. By then he had worked around the world and had been co-chair of Interpol’s expert group on the trafficking of women and children. In October 2012 he moved to Afghanistan as commander of the 30 AFP officers based there, the crowning moment in his career and also his toughest posting. “Not long after I’d arrived in Kabul I started to play the ‘what if’ game. Every day a series of scenarios and questions would run through my head: What if we’re attacked? What if the Taliban overrun our base? What if I have to get my people out of here? I had a whirlpool of questions that required solutions. Ultimately, I knew not only that lives were at stake, but that I was responsible for them.” It became an obsession. Unable to quell his mind with alcohol on a dry mission, he turned to painkillers.

When he moved back home to be commander of aviation based in Brisbane, he brought with him a series of health issues, and continued to self-medicate. At night he would either lie in bed obsessing over the memories of what he’d seen, and if he did manage to sleep he would be plagued by nightmares about the women and children he had been unable to protect. At work he was mentally absent. At home he drank, watched countless TV programs about war zones, and was mostly detached from his wife Kate and young daughter.

“I didn’t have the intention to commit suicide when I left home,” he writes of one of his daily commutes between the Gold Coast and his Brisbane office, “but somewhere during my one hour and 20 minute car trip it seemed the best solution to my many problems.” He was speeding towards a tree, a voice in his head encouraging him to continue, when he suddenly remembered his beloved grandfather and the rippling effects of his suicide. With seconds to spare, he slowed down and pulled off the highway. Later his doctor diagnosed PTSD, but fearing it would end his policing career, Edwards ignored the GP’s words for 18 months.

In 2015 he flew to the US to compete in the World Police and Fire Games, and found himself sitting under a tree. His head suddenly filled with buzzing and ringing sounds and he began to sob uncontrollably. Later that day he emailed Kate to say he needed help, and would finally tell his bosses about his mental state — even if it meant the end of his career.

AFP commissioner Andrew Colvin refused to accept Edwards’ resignation. Instead, his confession led to plans for the creation of an advisory group to help the force in future. Edwards was floored by his boss’s response. “He said he would prefer for one of his officers to tell him that they had problems, because it’s the ones who don’t acknowledge a problem who worry him.” But just as the advisory group’s plans were to be released in February 2017, a colleague committed suicide. Detective Leading Constable Susanne Jones died at the AFP’s offices in Melbourne, one of five AFP officers to have taken their life since then.

Given his own experience, a devastated Edwards penned an email to his 6500-odd AFP colleagues, alerting them to his own precarious mental health and urging them not to suffer in silence. “I was broken, and for the first time in my life I acknowledged it,” he told his co-workers. “…I’ve done some pretty tough things in my life, but acknowledging this and seeking help was by far the hardest thing I have ever done.”

That simple act marked yet another unlikely turning point as news of the email was picked up by The Canberra Times. That in turn led to Edwards being the subject of an episode of ABC TV’s Australian Story later in 2017, which in turn led to his new book. Yet despite his numerous public outings, and medical assistance, the repercussions of all he has seen and experienced linger. “Every time I talk about the book I get anxious and there’s nights of rough sleep; I relive it,” he says as he cradles his coffee. “I still have days where I can’t function. It stays with you. You’ll have good days and then it will drop. You think you can handle just about everything and you can fight it. And this is one thing I can deal with, but I can’t really fight it. You might win a battle here and there but you never win the war.”

Just before he began publicising his book, he was unexpectedly felled again. “The best way I can describe it is jumping off Niagara Falls and you have all of this mist and you feel yourself going down, down, and you can’t stop yourself, there’s nothing to grab on to. And I went down like that.” For three days he disconnected in almost every sense. “I like to think I’m reasonably pragmatic and [yet] I did all the things you shouldn’t do when that happens — went back to alcohol, went back to self-medicating, stopped taking my medications — because in my mind I thought, ‘I can’t be f..king bothered with this…’ I just went dark. I didn’t want to email anyone. I didn’t want to talk on the phone. You just go completely off site; that’s a natural thing I understand today. You sleep a lot. But then by about two and a half days, the old cliché, I gave myself an uppercut and said, ‘Come on, get yourself out of this. This is bullshit.’”

PTSD, he says, will be with him always. Prescribed drugs and a modified diet are parts of the new set of armour with which he hopes to shield himself as he embarks on the next part of his life; in August he’s retiring from the AFP after 34 years to work in the mental health field. His career has been rewarding but has had a considerable cost. It has coloured his view of humanity. “This is I guess part of the issue with policing in that you never really get to see the good. You deal with the [cases] and the victims move on. So unless they reach out to you later you rarely get people who will come back who have succeeded.” To remind himself about what is good in society, he reads the list of Australian honour awards religiously.

And yet, despite it all, he doesn’t regret that career. “I always get asked, ‘Would you do it again?’ And I say absolutely, at the drop of a hat. But if I did it again I would have looked to have been armed with the knowledge I have now, because I could have mitigated some of the things that have happened to me.”

Lifeline 13 11 14; Beyond Blue 1300 22 46 36. The Strong Man by Grant Edwards (Simon & Schuster, $35) is out on August 1.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout