How one teenager’s trauma triggered Hillsong’s #MeToo moment

Anna Crenshaw’s sexual assault complaint – involving the son of church royalty – might not have gone anywhere at all … if not for her own influential family network.

Anna Crenshaw might just be the last person you would expect to take a public stand against the Hillsong machine.

Her father, Ed Crenshaw, is a respected senior pastor within an evangelical church in Philadelphia. Raised in a Christian home, Anna Crenshaw was lured from the US to attend Hillsong College at the church’s Sydney headquarters. She was following in the footsteps of hundreds of other young Christians from America and around the world, who saw the chance for an adventure in a safe foreign land with sun, surf and the wholesome Hillsong brand.

Crenshaw was only 18 years old when she arrived in 2016. It wasn’t long before she was asked along to a gathering of Hillsong kids at a house near to Hillsong’s headquarters. As the evening wore on, she found herself seated next to a young man who, she recalls, was by now very drunk. The young man placed his hand on Crenshaw’s upper thigh and left it there. She says she just “froze”. Meanwhile, another young man at the gathering realised what was happening and offered to take Crenshaw and other students home. Crenshaw got up to leave. The young man wouldn’t let her go. In a statement she later made to Hillsong, she wrote: “He grabbed me, putting his hand between my legs and his head on my stomach and began kissing my stomach. I felt his arms and hands wrapped around my legs making contact with my inner thigh, butt and crotch.”

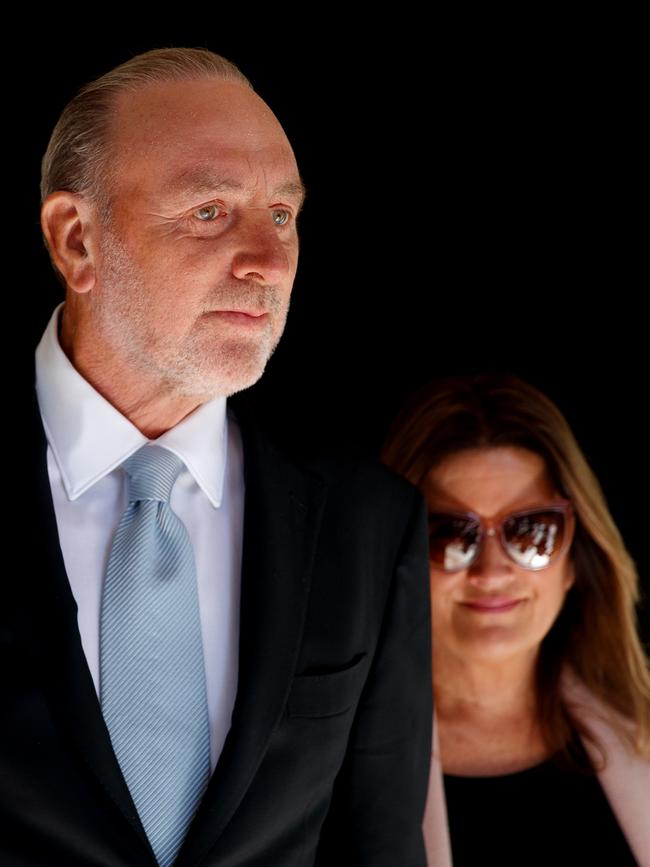

Crenshaw didn’t know it at the time, but the young man who had assaulted her was the son of Hillsong royalty. Jason Mays’ father, John Mays, was one of the Hillsong originals along with Brian Houston. He had also spent decades as a senior HR employee at Hillsong. Compounding the sin, Mays was married.

Crenshaw was left shaken by Mays’ drunken and highly sexual lunge. A counsellor she saw outside the church suggested she could report the perpetrator. It took 2½ years, but eventually, in 2018, she did just that. This was a step which she, as a young foreign student, found “scary” and “intimidating”. In so doing, though, Crenshaw ran into a thicket of old friendships that existed at the very top of the Hillsong hierarchy. When she summoned up the courage to inform Hillsong, she was directed to the church’s head of pastoral care oversight, Margaret Aghajanian. Aghajanian is married to George Aghajanian, Hillsong’s long-serving general manager, a man who has long been a driving force of Hillsong’s success.

Crenshaw’s concerns, which became a complaint, might not have gone anywhere at all if it not for her own influential family network. Unlike most, Crenshaw had the necessary backing to take on the Houston empire. Her father, Pastor Ed Crenshaw, called in the support of American evangelical royalty – lawyer Boz Tchividjian, who is the grandson of legendary preacher Billy Graham. Tchividjian threw his weight behind Anna Crenshaw’s decision to speak out against Hillsong; it was, he said, “a bold step forward in bringing darkness to light” inside the Houstons’ church.

Mays was ultimately found guilty of indecent assault at a magistrate’s court hearing and was given a two year good behaviour bond, no conviction recorded. The ordeal scarred Crenshaw who for years had been a huge fan of Hillsong.

“There’s a lot of talk about empowering women through the work of Bobbie Houston (Brian’s wife),” she says. “Yet that wasn’t the case when I reported. They spent more time making excuses for the perpetrator.”

Ed Crenshaw, says Hillsong has developed “a habit of self-protection”, citing how the church had treated the sexual assault victims of pastor Frank Houston, Brian’s father. Anna Crenshaw decided not to let the matter rest with the court finding against Mays. She sued Hillsong for the hurt and pain from the ordeal.

“I feel like they never took any accountability for what happened,” she says. “And anytime they did talk about what happened, they did so in a way that further hurt me. When I reported, I felt like I was doing the right thing. And I thought, ‘Okay, now I can move on with my life’. I didn’t expect it to be years more of them treating me horribly.

“When you go to your leaders or the people who are meant to protect you, and they turn a blind eye or don’t take it seriously, they make the trauma worse. And I feel like they did that multiplied by a hundred. And so it really kind of destroyed the life that I had built in Australia.

“But at Hillsong it was such a hierarchy … the people who were in the in-crowd got there by marrying someone who was already in the in-crowd. And it was a lot about power and position. And it was very obvious, as students, that we were not a part of that. And so, for me, that made it a lot harder to report anything.”

Within the tight-knit student community, Crenshaw’s case became a symbol of an entrenched culture of insiders and outsiders. She would learn much later that Hillsong had been keeping Brian Houston’s own transgressions with two women a secret at the very time when the church was dealing – or failing to deal – with her allegations.

In the aftermath of Crenshaw’s legal action, Tchividjian reflected on what her courageous step showed about Hillsong and other megachurches like it.

“They handled it in a despicable way that seemingly puts the protection of the institution clearly as a priority over the protection and care of the victim, which is, in my opinion, the antithesis of the very gospel they preach,” he says. “So it was all about institutional self-protection, and even if that requires the sacrifice of a vulnerable and abused young woman.”

Hillsong’s treatment of college student Crenshawcrystallised a fundamental truth about its project: there is a special clique of people at the top who play by different rules from the rest. A select group of Houston family and friends could seemingly do as they pleased, with the protection of an old boys’ network at the top. For some, this was the very antithesis of the Christian message. Perhaps it is the logical end point when a religious movement is hijacked by a greed-is-good ethos. With the passing of the years, a new generation was rising to take over the Hillsong empire. But there was nothing new about this group. They were the so-called legacy kids: the privileged sons and daughters of the church founders. They were the new ruling elite, the inheritors of Hillsong’s wealth and power.

But they were to meet their match in the young Christian women who were disgusted by what they saw and cared enough about their faith to do something about it. Fiona Jones* is one of these women and she remembers very clearly the night her illusion about Hillsong was shattered. It was the moment she described as “the beginning of the end”.

“I had been invited to a New Year’s Eve party in Bondi,” she recalls. “I wasn’t long out of high school. The Bible College had a very strict policy for youth leaders with alcohol, with sex. You know, it was very highly conservative.

“I walked in and the room was filled with the Hillsong ‘who’s who’: the young people who appeared on albums and, you know, some of them even preached on weekends. They were all legacy kids, so their parents were prominent figures of Hillsong. Everyone there was absolutely sloshed. And it was at this moment that I was really confused because I was like, ‘What? What is happening here?’

“I saw a staff member who was married and her clothes were sort of falling off. She was dancing with someone who wasn’t her husband. And I remember going to the bathroom and there were loads of people in there. Obviously there were weird things happening. I saw drugs. And I felt so uncomfortable I just left the party. I hopped on the bus, and never told anyone, but just came home.”

The behaviour Jones witnessed was the very opposite of the purity doctrine that was enforced upon the young people who were attracted to Hillsong.

“The emphasis of youth camps and youth events and Friday-night youth group was that your devotion to God is shown in how you abstain from substances and abstain from sex. But here they were doing the opposite,” Jones explains.

“That was the beginning of [my] seeing that there were rules for some that didn’t apply to everyone. And that was just like a moment of my innocence going. I think I was shattered because these were the people I watched on Hillsong DVDs, talking about wanting to make a difference and about having a devout life.”

While there was favoured treatment for an inner circle of Hillsong, Jones also discovered there was a well-developed system for silencing dissent. And another young woman, Helen Smith*, saw direct lessons from the treatment of Crenshaw.

“For a lot of us when you have this #MeToo movement happening, when you have the broader evangelical church being okay with Donald Trump and his behaviour, you see more and more how your voice never did matter within Pentecostal churches,” Smith says. “And then you see the Anna Crenshaw thing, when you see that Brian seems to have not wanted to acknowledge what his behaviour represents in how he treated women.

“I said to my husband at one point – particularly when the Jason Mays and Anna Crenshaw thing blew up – that I wasn’t sure that I was okay with taking my kids to church, which is what I grew up expecting I would do. I didn’t see it as a safe place anymore for me or my children. The way they handle serious allegations … they think that they’re above the law.”

Jones saw the silencing of dissent on several levels. “I think the thing that shocked me was just being told explicitly by another woman, that if I wanted to get anywhere, then there were rules I had to follow,” she says.

The discrimination built into the system was repellent for those who took their religious beliefs seriously. It was younger women in particular who could no longer abide the hypocrisy of the church leadership.

The world had changed a great deal in the four decades since Hillsong set up shop in the aspirational white middle-class suburbs of the Hills district of northwest Sydney, but the church had failed to keep up with the times. Jones confronted a disjunction between the outside world and the world of the evangelical bubble.

So what is a woman meant to do at Hillsong when nearly every board member and every senior manager for the past 30 years has been male, and an old friend of the Houstons? The answer is be like Bobbie.

Bobbie Houston – or Mother Dove, as she came to be affectionately known – built a whole new branch of Hillsong called the Colour Sisterhood, representing what Hillsong women should be. She was the yin to Brian’s yang. For four decades, Brian and Bobbie Houston were the royalty at the top of Hillsong, the happily married husband-and-wife team. They radiated contentment with their prosperous lives and their solid family values. They were also a living example of the complementarianism that is at the heart of successful male-female coupling at Hillsong, modelling for the congregation how couples should be and how mums and dads should raise their kids.

“There are jokes about how every woman in Hillsong dresses the same, especially the women on staff. They all wear these long kimonos. They have Tiffany bracelets. They have the big white watch that Bobbie Houston wears. They all straighten their hair, even if they’ve got curly hair. They all wear leather boots that are high-heeled. It’s a very strong archetype.

“And you have to be funny and sexy. And all of these things at once. You know, if you want to be overweight, if you want to be a girl who doesn’t wear makeup, or doesn’t straighten her hair, you’re not gonna get ahead and become you know, the pastor’s wife.

“These women had a Thursday morning meeting where you sit down and Bobbie tells you how to be the perfect woman and you’re literally there writing down you know, all of these tips and tricks Bobbie’s telling you.”

For every young woman who quietly shifted her allegiance away from the Houstons, there was a point of no return. Helen Smith had been raised in a Christian family but found Hillsong’s excesses to be too much. “Hillsong was actually the antithesis of Jesus and the gospel. So I think it just seemed to be the complete opposite end of the spectrum of what my faith was,” she says.

For Smith, the breaking point was what she calls the “entitlement” of Houston and his close family. She came to know of the personal errands that were being done for the Houston family using staff paid by the church.

By the beginning of 2022, the dark clouds had well and truly gathered over the Hillsong enterprise. The scandals had banked up. The past was catching up.

In the US, Houston’s New York campus had imploded. His star preacher and family friend Carl Lentz had caused an almighty spectacle with a very public moral implosion amid infidelity scandals.

Separately, the Crenshaw matter, which started in Australia, had seeped over to the US, where the respectable and reputable end of the American evangelical movement had swung in behind the Crenshaws and against Houston.

In mid-2021 in Australia, NSW Police charged Houston with the crime of concealing information on sexual abuse committed by his father, Frank. (Brian Houston was acquitted of this in August 2023.) The ghost of more than 20 years past had finally returned; Houston had learnt of his father’s crimes back in 1999. As a result of the police charge, Houston temporarily stood aside from Hillsong business.

Behind the scenes, the rumbling thunder was coming closer to home. By early 2022, unknown to the wider church community, some Hillsong elders had become uneasy about new information that had surfaced about Houston’s past. With Houston having stepped aside, the veil was lifted on some closely held secrets.

Hillsong’s elders are the church’s most illustrious figures; some date their association with the church back to its earliest days. They are meant to act as spiritual counsellors and to provide wise advice to the church. But they were now hearing disturbing details about Houston’s behaviour for the first time.

On Friday March 18, 2022, at 9.30am, a Zoom meeting began, the purpose being to inform staff of news on Houston. Thirty minutes later, a recording of the proceedings reached me via a secure email. The recording captures the biggest moment in the church’s 40-year history: the moment when Hillsong announced it was the end of the line for the church’s charismatic founder and leader, Brian Houston.

Interim senior pastor Phil Dooley was about to reveal long-held secrets on the behaviour of Houston. Call it a controlled explosion. The first incident had taken place some ten years before, around 2013. This involved Houston text messaging with a female member of staff. “[It] ended in an inappropriate text message along the line of, ‘If I was with you, I’d like to give you a kiss and a cuddle, or a hug,’ words of that nature,” Dooley said. “That particular staff member was obviously upset by that and felt awkward, and I think responded to that, went to George Aghajanian and decided that she would like to leave staff because of that. And so she did.”

The second incident, he said, had taken place in 2019, during Hillsong’s annual conference, the church’s big set-piece event featuring celebrity pastors from Australia and the US, and which attracts tens of thousands to Sydney’s Olympic Park stadium.

Here, after a long day, Brian Houston had been drinking at the bar of the Pullman Hotel with a group of Hillsong people, with drinks finishing late at night. The group included a woman who was a major donor to Hillsong via the Kingdom Builders scheme. She had paid her fee to attend the conference.

“Later that evening,” Dooley began – and then interrupted himself to note that “Brian had also been taking anxiety tablets.” Dooley resumed: “And later that evening, he [Pastor Brian] went to attempt to go to his room. Didn’t have his room key, and ended up knocking on the door of this woman’s room. And she opened the door, and he went into her room.

“The truth is, we don’t know exactly what happened next. This woman has not said that there was any sexual activity. Brian has said there was no sexual activity. But he was in the room for 40 minutes. He doesn’t have much of a recollection because of, he says, the mixture of the anxiety tablets and the alcohol.”

The revelation that a drunk Houston had lost his room key and somehow then ended up spending 40 minutes in a woman’s hotel room was news that immediately grabbed headlines, in Australia and internationally.

Of itself, the revelation was enough to end Houston’s association with the church. It also caused massive ructions among pastors in the US. Hillsong could no longer ignore the noise growing around Houston’s transgressions. It was unimaginable that Houston, the founder and figurehead of the Hillsong phenomenon, could fall, but fall he would, pushed out by the Hillsong board – in the name of creating a “healthy” church.

The board would not have imagined that the removal of Hillsong’s founder and global senior pastor would open the floodgates in a way the church had never experienced before.

As young female dissidents who had left Hillsong mobilised quietly behind the scenes, another woman, still inside the church, Natalie Moses, was preparing to make a very loud noise indeed. She would become the first-ever insider to blow the whistle on the behaviour of the church’s most senior figures. Her revelations about the church’s finances came crashing out in the aftermath of Brian and Bobbie Houston’s departure, and were driven, in part, by her disgust at how the church had buried the truth about Houston.

Moses and her husband, Glen, had been part of the Hillsong scene in the Hills district for three years before Moses took up a role managing the church’s governance – a position that gave her access to information on the money flows into and out of the church. Motivated by her strong sense of how a Christian organisation should act she brought an outsider’s eye – and the experience of years in other charities – to an organisation that had been run by a small clique of Houston family and friends. ●

* Names have been changed.

Postscript: In November 2023, Brian Houston announced via X, formerly Twitter, that he and Bobbie would launch an online church in 2024.

This is an edited extract from Mine is the Kingdom: The rise and fall of Brian Houston and the Hillsong Church, by David Hardaker. Out February 27 through Allen & Unwin.