How Mick Jagger built brand Rolling Stones

The frontman’s business acumen ensured the world’s biggest band stayed the longest-running rock ’n’ roll enterprise of our times. Take notes, Taylor.

Mick Jagger was supposed to be singing Start Me Up in stadiums across the US this year. The buzz in the music business was that a tour was booked. Instead, the Rolling Stones in April made an inside joke via social media: a 1972 photograph of a debauched Keith Richards next to a sign that reads: “Patience Please… A Drug Free America Comes First!”

The message? Stones fans can’t always get what they want.

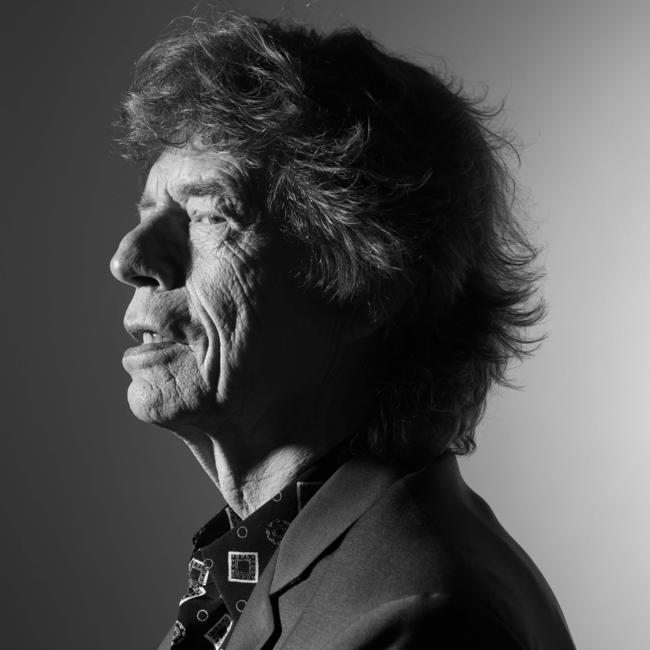

“I wanted to have the summer off,” Jagger says with a laugh during a video call from Italy, dismissing the speculation about illness or injury. He deserves “to take it a bit easy”, as he puts it. The Stones may not tour as exhaustively as they once did, but they remain among live music’s biggest draws, hitting the road nearly every year for the past decade. Jagger has a six-year-old son with his girlfriend, Melanie Hamrick. In 2019, he underwent a successful heart procedure. This July, he turned 80.

On top of all this, the Rolling Stones’ promotional machinery has been cranking into high gear to support the release this month of Hackney Diamonds, the band’s first album of original material in 18 years. Tackling the album and touring simultaneously would have wiped him out, Jagger says. So he made an executive decision to stay home. A happy, healthy Mick Jagger is a happy, healthy Rolling Stones. It’s the kind of clear-eyed, far-sighted management acumen that has helped the band stay the longest-running rock ’n’ roll enterprise of our times.

Jagger isn’t planning to just lounge by the pool. There’s a photo shoot in New York City. Band interviews. Music videos to make. When he speaks with me from the Italian island of Sicily, having recently hosted his children and their partners (“it was very fun and – um – a bit full-on”), Jagger is relishing a little peace and quiet. The following week, he’s planning to fly to Paris to see friends and catch an Imagine Dragons show.

“I’m very lucky to be so healthy,” he says, downplaying how he eats carefully and hits the gym almost every day. “It’s luck more than anything. Just genetic.”

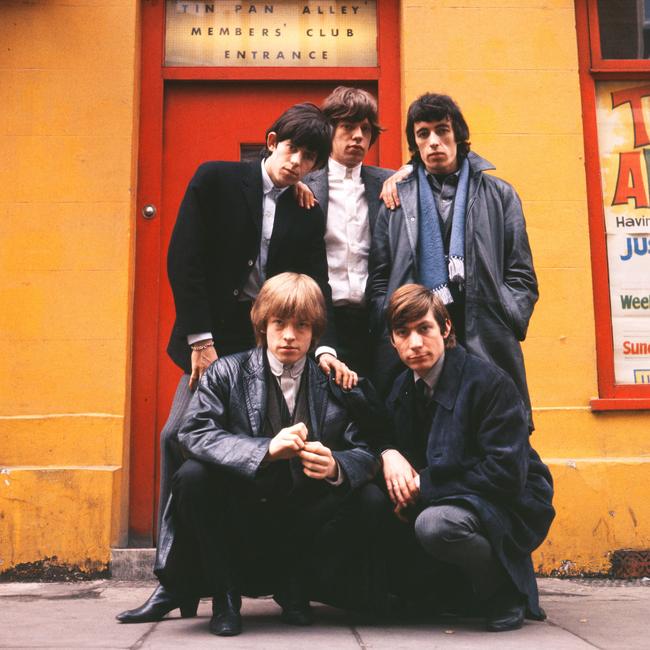

The rock ’n’ roll generation is disappearing right before our eyes. The run of recent obituaries can induce a kind of vertigo. Yet the Rolling Stones have lasted, leaving us with the illusion that mortality can remain tomorrow’s problem. The Beatles didn’t make it a decade. The Stones, which formed in 1962, are in their seventh. The first time Jagger remembers being asked if the Stones would ever tour again was in 1966. Two years later, Rolling Stone magazine ran a cover story on their comeback. When the band released their last huge hit, 1981’s Start Me Up, they were viewed by many as over the hill. People have been talking about the Stones being “old” for 50 years now.

How has this band – more than any other act of their era – kept it together? The most compelling answer may involve a London School of Economics dropout named Michael Philip Jagger – who inadvertently became a business legend as well as a musical one. Jagger says he never set out to build rock’s first behemoth brand. Yet he forged a trail that led artists away from naivety and potential exploitation to unabashed commercialism, à la Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour.

It was an act of self-preservation, he says.

“I don’t actually really like business, you know what I mean?” he says. “Some people just love it. I just have to do it. Because if you don’t do it, you get f..ked.”

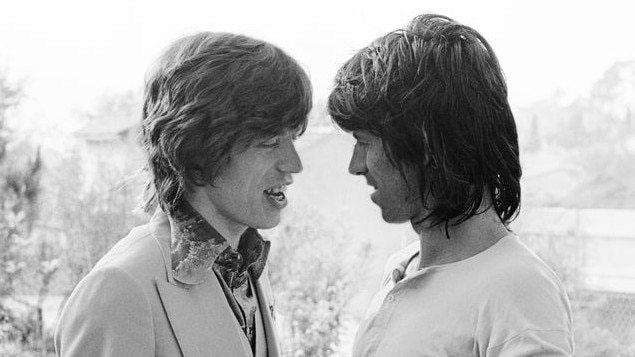

Rolling Stones orthodoxy says it was Keith Richards who kept the band together when it nearly unraveled at various points, especially during the 1980s. But there is a strong case to be made that if it weren’t for Mick Jagger, the Stones would have fallen apart by now.

Mortal threats over the decades have been numerous: Brian Jones’s tragic instability; major conflicts with business partners; Keith Richards’s heroin addiction; the band’s intense infighting that Richards once called “World War III”; the 2021 death of the band’s beloved drummer, Charlie Watts.

But Jagger’s serendipitous mélange of skills somehow made him an ideal CEO to see them through.

It’s not only that Jagger is one of the greatest frontmen in rock history. Not simply his onstage athletics (running a mini-marathon every night), or his business smarts. It’s his level-headedness – his instinctive aversion to self-mythologizing and overexposure. Musically, it’s his openness to new sounds, whether it’s pop, reggae or disco. Perhaps more than anything, it’s his lack of sentimentality.

The Stones’ resilience speaks to the long shadow of the boomers, but it also signifies something decidedly counter-countercultural: the need for pop musicians to be businesspeople. The Stones weren’t financial savants when they started. They learned the hard way – by having serious business problems. To this day, they don’t own the copyright to huge early hits like Satisfaction. Sound familiar? Even in 2023, artists as powerful as Taylor Swift can still struggle to own and control their work due to their early decisions.

Mick Jagger was ahead of the curve: the Stones piled into merchandise, branding and sponsorships at a time when making money was verboten. They took the bullets and today’s artists collect the cash. “One of the things I’m really proud of, with the Stones, is that we pioneered arena tours, with their own stage, with their own sound and everything, and we also did the same with stadiums,” Jagger says. “I mean, nobody did a tour of stadiums.”

If you’re wondering why the Stones took 18 years to complete a new album of original songs, there’s an utterly unsexy reason: they kept going into the studio and coming out empty-handed.

Richards likes to jam in studios in a less structured fashion, cultivating the conditions for inspiration – a great groove, an unforgettable melody. But Jagger is pragmatic and results-oriented. He didn’t particularly enjoy the long, drug-addled sojourn in the French Riviera that produced the Stones’ 1972 classic Exile on Main St. He’s no robot, but he wants recording sessions to quickly translate into songs.

So the Stones were in a rut. To extract them, Jagger set a tight schedule and hired a new producer. Those efforts yielded Hackney Diamonds, a relatively direct, no-frills mix of rockers and ballads that seems to encapsulate the many different eras of the Stones.

After the band’s last European tour ended in August 2022, Jagger sat down with Richards. He said the Stones should step it up a notch, even though no one was particularly excited about some of the material they’d recorded. Richards agreed.

But Jagger also wanted deadline pressure. “What I want to do is write some songs, go into the studio and finish the record by Valentine’s Day,” he told Richards. “Which was just a day I picked out of the hat – but everyone can remember it. And then we’ll go on tour with it, the way we used to.”

Richards told Jagger it was never going to happen.

“I said, ‘It may never happen, Keith, but that’s the aim. We’re going to have a f..king deadline,’” says Jagger, making a karate-chop motion. “Otherwise, we’re just going to go into the studio for two weeks and come out again, and then six weeks later we’re going to go back in there. Like, no. Let’s make a deadline.” (Richards declined an interview request.)

Jagger says he was attempting to replicate the quick turnaround of 1978’s Some Girls, a punchy, New York–inspired album led by Jagger that included the hit Miss You and reinvigorated the band. “Not that you’re rushing,” Jagger says. “But you’re not, like, doing take 117. So that you don’t get bogged down in conversations about whether this song’s a good one, whether this song’s worth it.”

The Stones had already banked a couple of tracks featuring the late Charlie Watts on drums, including Mess It Up, which conjures the same disco-ish spirit as Miss You. But “the rest of it was done all real quick”, Jagger says. The goal was to give the recordings urgency. “Even if it’s a nice song, if it’s not done with enthusiasm it doesn’t really get to you, does it?” he says.

To freshen things up, Jagger tapped Andrew Watt, 32, a buzzy, Grammy-winning pop and rock producer whom he met through Don Was, who produced the Stones’ 1990s and 2000s studio albums.

“Mick serves people up. And Keith keeps them – or throws them out,” Watt says.

Starting last November, Jagger, Watt and the Stones entered Henson Recording Studios in Los Angeles and, over the ensuing months, whittled down hundreds of potential songs to roughly 25 tracks. In a departure for the band, Watt has writing credits on three compositions that made the album, including Depending on You, whose chords Jagger, Richards and Watt wrote together after chucking out some of Jagger’s own contenders.

“Keith and me and Andy wanted to do a ballad, and I kept saying, ‘I’ve got these great ballads, let’s do this one!’” Jagger says. “They go, ‘Well, that’s not really good enough.’ ‘OK, here’s another one!’… They said, ‘No, let’s write one from scratch.’”

The album’s guest list is a reunion of high-powered musician friends, including Paul McCartney (contributing bass), Elton John (piano), Stevie Wonder (piano) and Lady Gaga (vocals), the last of whom happened to be working in the same studio during one session. Bill Wyman, the Stones’ 86-year-old original bassist, who stopped performing with the band in the 1990s, shows up too.

The deadline worked, Jagger says. The Stones recorded basic tracks in four weeks, eventually settling on 12 songs. Hackney Diamonds was finished a few weeks after Valentine’s Day. “They don’t sound like 80-year-old men on this record,” says Watt.

A lengthy queue for vinyl-record manufacturing, however, meant the Stones couldn’t release the album immediately. “I met with the heads of the record company and said, ‘Well, when can you put it out?’” Jagger says. “And they said, ‘What about Christmas?’ I said, ‘F..k off. Christmas? No.’” The compromise: October. The band is talking about touring the US and hopefully elsewhere next year.

In Sicily, Jagger appears relaxed and jovial, wearing a white V-neck T-shirt and unbuttoned overshirt. He is fluid and lithe. He cracks jokes. His summer off is clearly working its magic. I ask Jagger if he thinks this could be the Stones’ final original album. “No – because we have a whole album of songs we haven’t released!” Jagger says. “I have to finish them. But we got three-quarters of it done.”

He bristles at the notion that he’s all business while Richards handles the art (“I love just going to my music room and turning on a drum loop and making a song – that’s fun”). He has his own personal failings and acknowledges he has contributed to the band’s internal tensions.

-

“I haven’t been perfect,” he says.

-

His desire to build his own artistic identity away from the Stones brought things to the brink with Richards in the 1980s. In general, he doesn’t like indulging in discussions about the Stones mythos. “I never look back,” he says.

Yet he reluctantly agrees he has had a stabilising influence on the Stones. Time and again, he’s kept things going. “I mean, it is kind of my role, you know? I think people expect me to do that,” he says. “I don’t think anyone’s saying, ‘Oh, I should be doing the “clarity” role.’ I don’t see Ronnie [Wood, the band’s longtime guitarist] saying to me, ‘Mick, I think you should retire from the clarity role and the vision role and I’ll do it.’ No one else wants to do it! I just got dumped with it. And I made a lot of mistakes, when I was very young. But you learn.”

The roots of Jagger’s shepherding of the Stones go back to Dartford, England, where as a boy he first met Richards, who lived one street away. Jagger’s father was a PE teacher. As a teenager, Jagger performed in clubs while also studying finance and accounting at the London School of Economics. He eventually dropped out, a decision that made his father furious.

After the Stones took off in the 1960s, they felt they got burned by their own team. They had hired the US music-business accountant Allen Klein, impressed by his efforts on behalf of other artists. Klein negotiated a new deal with the Decca label, winning the Stones a huge million-pound advance payment for their next album. But eventually Klein and the Stones ended up falling out. Among the issues was that Klein got ownership of the Stones’ songs. As a result, it’s his company, ABKCO Music & Records, that today owns the copyrights for the Stones’ pre-1971 music. Klein died in 2009.

Jagger brought on a private banker, Prince Rupert Loewenstein, to rebuild their business. It turned out the Stones didn’t just lack cash – they owed a large amount of back taxes, creating a crushing debt spiral given Britain’s high tax rates. The Stones sued Klein and became tax exiles in France in the early 1970s to get into the black. (The litigation continued for many years.)

“The industry was so nascent, it didn’t have the support and the amount of people that are on tap to be able to advise you as they do now,” Jagger says. “But you know, it still happens. I mean, look what happened to Taylor Swift! I don’t really know the ins and outs of it, but she obviously wasn’t happy.”

During the 1970s, the Stones launched giant tours – their 1972 US venture, for example, became a pop-culture event much like Swift’s Eras Tour – that ushered in the modern concert era. The early Stones tours were inefficient from a business perspective. But over time, Jagger helped transform the band into a well-oiled live-music machine, one that repeatedly delivered the top-grossing tours ever.

Richards’s heroin addiction deepened in the 1970s. That, along with the humiliating Klein affair, pushed Jagger to take a more central role in the band’s business. Perhaps Jagger’s efforts during this period indirectly saved Richards’ life. Yet tensions between the two escalated, reaching their darkest point in the mid-1980s, coinciding with the band’s 1986 album Dirty Work. Richards wanted to tour it. Jagger said no, partly because Richards and even Charlie Watts were both in such bad shape with drugs. “In retrospect, I was a hundred percent right,” Jagger told Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner in a 1995 interview. “It would have been the worst Rolling Stones tour. Probably would have been the end of the band.”

“There were a lot of disputes,” Jagger tells me now. “And then, with Charlie not functioning too… probably because it was his way of escaping. You get to a certain age and you don’t want to have to deal with this stuff. I mean, everyone was taking drugs, the 1980s was a big drug period. Well – so were the 1970s! And the 1960s!”

Jagger’s guiding hand extends to the music too, of course. When I envision the songwriting partnership of Jagger and Richards, I imagine an atom, with an electron darting around a nucleus. Richards is the nucleus, the band’s “soul”, the eternal keeper of its musical flame. For decades, he has been married to a Chuck Berry-esque rock ’n’ roll sound, played in his own inimitable, staccato way. But the generative core of the Stones lies not in him alone, but in the tension between him and Jagger, who, as the electron, the wandering spirit, is flighty, adventurous and fickle, dabbling in new genres and bringing them all back home to the Stones. Thanks to Jagger’s open-mindedness, the band has undergone striking stylistic shifts over time: pop, psychedelia, country rock, disco, new wave.

Looking to the future, I ask Jagger if the Stones have plans to sell their (post-1971) catalogue. He says no. He knows a tidy lump sum of cash might leave a less byzantine legacy for the band members’ heirs, but “the children don’t need $500 million to live well. Come on”. Maybe it’ll go to charity one day. “You maybe do some good in the world,” he says. He’s also not planning to publish an autobiography.

He is, however, cognisant that the business of the Rolling Stones will outlive him. “You can have a posthumous business now, can’t you? You can have a posthumous tour,” he says. “The technology has really moved on since the ABBA thing [the pop group’s recent Voyage virtual show], which I was supposed to go to, but I missed it,” he says. It seems logical to Jagger that one day, fans of the Stones and other older bands will watch such productions, while sifting through vaults of previously unreleased music. The constant repackaging of older music, though – of which the Stones are masters – he finds “pretty boring”.

The problem with old age, Jagger says, is that people feel helpless, useless and irrelevant.

At least for now, he doesn’t appear to have those afflictions. While he gets treated differently (“people get out of my way, in case I fall over,” he jokes), his recovery in 2019 was notably swift (“in two weeks, you’re in the gym”). Apart from the countless Stones fans giving him purpose, there’s his six-year-old son Dev. “I have this really wonderful family that supports me. And I have, you know, young children – that makes you feel like you’re relevant.”

Jagger is also growing more comfortable with social media. There’s a humorous line on Mess It Up, from the new album, where Jagger sings: “You shared my photos with all your friends / You put them out there, it don’t make no sense.” As someone who’s been public for 60 years, Jagger still wants to keep some things private. But he expresses pride in his posts, which show him popping up here and there around the world. His girlfriend, Melanie, a former ballerina, has her own online presence. “It’s just a fact of life,” Jagger says. “But there are boundaries I like to have.” In some ways, social media has become less threatening. “People used to post stuff and everyone would think, whatever girl you’re standing next to… ‘Is that your new girlfriend?’ You know. But everyone knows now,” he says.

And Jagger still loves to dance, of course.

In July, he hosted an 80th birthday celebration in London – first a family dinner for around 50, and then a larger party for 250 at a nearby club he rented out. Among the celebrants were Jerry Hall (with whom Jagger shares four children) and Lenny Kravitz (who guested on Jagger’s 1993 solo album). There was a Cuban band performing.

I ask Jagger if 80 feels different to 70, facing his mortality. He shrugs off the question with the boyish playfulness – and matter-of-factness – that has served the Stones so well.

“They’re both big numbers,” he says. “One’s more than the other one.”