Macquarie Bank’s Sydney airport deal made it a target

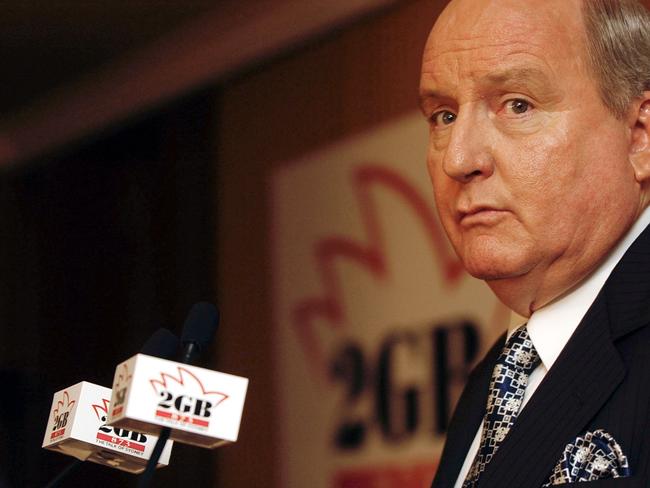

At its zenith, Macquarie Bank was a fearless and ravenous enterprise. But one deal — and Alan Jones — would bring the party to a rude end.

Say what you like about Richard Branson and Virgin, but the man knows how to drum up publicity. “Macquarie: what a bunch of bankers” was the slogan that appeared on Virgin-sponsored billboards, and briefly in the livery of a few Virgin Blue aircraft, in the dispute with Macquarie Bank over access to Sydney Airport in 2002.

Given sufficient time, pretty much everyone would probably end up on the sharp end of a Virgin slogan at some point in their corporate existence, so in isolation one shouldn’t read too much into it. But it wasn’t in isolation. All of a sudden, everywhere Macquarie looked there was bad press. Alan Jones, the obtuse and thunderous radio broadcaster who by the early 2000s had become one of the most powerful (and loud) voices in Australian society, had Macquarie in his crosshairs. CEO Allan Moss’s temperate nature was being tested by endless questions about the moral justification for just how much money he was earning. There were doubts about the whole Macquarie model, about governance in its satellite funds, about behaviour around coal mines and airlines and related-party transactions. It got to the point where Warwick Smith, a former government minister who had joined in 1998 with a dual mandate for telecoms banking and to build out the communications function, set up a daily morning council that the comms team openly referred to as a war room. “Every morning we would sit down with senior management and say: here’s the story, how are we going to deal with it?” says Matthew Russell, a member of that war room. “How do we get ahead of the news cycle?”

Macquarie had gone from being seen as a scrapping homegrown underdog battler to that uniquely Australian phenomenon: the tall poppy. And as Bob Hawke, or at least a film version of him, had it: “We have a way of dealing with tall poppies in this country: we cut their heads off.”

How had this happened? It had all been going exceptionally well. Every year of the 2000s until the 2009 financial year, the one that includes the global financial crisis, would be an all-time record, each one eclipsing the last, sometimes by as much as 60 per cent or more year on year. Moss was presiding over a fearless and hungry enterprise that believed it could do anything. Never shy of an internal restructuring, Macquarie had reshaped itself yet again in 2001. It would elevate Nicholas Moore to pole position to succeed Allan Moss, while sidelining corporate advisory doyen Alastair Lucas. The place became siloed even by the usual standards of investment banking, and no matter how much the top brass said about seamless cooperation for the good of the client, there was vibrant internal competition that would sometimes turn to open contempt.

“There was a healthy mistrust of each other,” says Simon Wright, head of fixed income and foreign exchange. “It was siloed, a kind of sibling rivalry, very strongly so during the nineties and noughties, though less so today. People who were hired in the eighties and nineties were quite different animals to what they are today, and now people play nicer.” Wright says that today hiring is conducted specifically to encourage collegiate collaboration. Not then. “Previously, you would hire people to be hungry animals.” One banker recalls the irritation in the commodities business towards investment banking. “The MacCap guys thought they were the kings. They were the guys in flash suits talking loud in the lifts.” Another, in corporate services, recalls: “The only thing that united the groups was hatred of the Property Group.” A third: “I think the group heads would happily have ripped each other’s heads off.”

The early 2000s would probably be the nadir – or zenith, depending on your love of a good scrap – of this situation. There was a dark humour to it. At the top, Allan Moss would project an unflappable serenity. Throughout the 2000s, as the maelstrom of a fabulously complex and successful business broiled beneath him, it was quite commonplace to see him strolling up the pedestrianised concourse outside the new office. “You’d see him walking up and down Martin Place like he didn’t have a care in the world,” recalls one. “He just came across as calm and cool and not really fazed by anything. And then you’d see the group heads and they would be fighting each other tooth and nail every single day. I mean, they were all just horrible to each other.”

Beneath the chief executive, Macquarie’s next significant tier is the Executive Committee, or Exco. In the early 2000s, this broke down thus: Nicholas Moore (later Michael Carapiet) for the investment banking group, Andrew Downe for treasury and commodities, Ottmar Weiss for equity markets, Bill Moss for banking and property, David Deverall for funds management and Peter Maher for financial services. There are some extraordinarily strong personalities in that group. Maher’s perspective, as an outsider drafted in from Westpac to build a retail business within Macquarie, is interesting. “I had some of the most direct conversations one-on-one with other group heads, and as they say, you don’t turn up to a gunfight with a feather.”

-

Macquarie had gone from scrapping underdog battler to tall poppy

-

Allan Moss was not blind to this commotion; he was relaxed about people competing, given a natural overlap between some businesses. “It was never a problem,” he says now. “Around the edges, there’s always a little bit of friction. I didn’t spend my days worrying about the relationship of one executive committee member to another. I always had the view that really good investment bankers are often a bit difficult. And I always felt that aggressive energy could be pointed outwards.”

Macquarie was growing in all directions: geographically, by product line, by size, by profits. It must have been exhilarating, we say, to have all these engines of growth delivering, but with so many spinning plates, there must be a point at which you can’t be on top of everything all the time?

The reasons Sydney Airport became a magnet for public opprobrium were varied. Some were structural; some about market perception of value. Some were the distinct emotional connection people seem to have with the infrastructure they use, a curious phenomenon Macquarie would have to learn to deal with all over the world. Airports had been a natural extension of Macquarie’s burgeoning infrastructure theme, and grew the same way roads did: by starting with advice and then moving on to development and ownership. In the 1999 financial year Macquarie advised on the $467 million acquisition of airports in Adelaide, Coolangatta and Parafield, as well as the Airtrain city link to Brisbane Airport and a $1.9 billion borrowing program for Sydney Airports Corporation. All of this had been preparatory work around a broader goal: Sydney Airport. The government had commenced a formal sale process, and Macquarie reasoned that having a listed vehicle would be a useful way to provide consortium investors with an exit when they needed it. The idea of owning Australia’s true gateway airport transfixed the city: there were about 20 expressions of interest that eventually coalesced into three serious bidders involving, between them, pretty much every bank, law firm and accountancy house active in Sydney.

But then came the 9/11 terror attacks in 2001. Several Macquarie staff escaped the World Trade Centre towers, among them economist Rory Robertson, who was at an economics conference on the ground floor. Beyond the human horrors of that day was an immediate challenge for Macquarie: it was in the market with a $500 million capital raising at the time. “It was big, and of great strategic significance, because we wanted it in order to be able to buy assets in the infrastructure business as seed assets for new funds to be listed subsequently,” says Allan Moss. “And I got a phone call at about midnight from one of my colleagues saying two planes had hit the World Trade Centre in New York.”

Moss met with Peter Mason of JPMorgan, the joint underwriter, at seven the next morning to decide whether or not to pull the deal, given that Wall Street, in the immediate debris zone of the fallen towers, was shut for the foreseeable future. They opted to go ahead. “It was a dreadful day,” Moss says. “In every dealing room in every country in the world, the TV just had that ghastly scene of the towers falling all day. That was the backdrop to the deal.” Richard Sheppard, Moss’s deputy at the time, recalls that the book had been filled overnight but the overseas investors all pulled out. “We had enough friends and supporters to complete the capital raising,” he says.

Moss recalls it as the only capital markets deal done in the world that day or for several afterwards. “We thought it was the right thing to do. Morally it seemed like one shouldn’t give in to terrorists if one doesn’t have to. But that wasn’t the reason for doing it, we were doing it because we were able to and it was a sensible idea.”

-

Staff came out of the meeting to find a load of Virgin flight attendants with super-soakers

-

The 9/11 attacks had an immediate impact on the aviation industry, and in Australia they were followed in a matter of days by the collapse of Ansett, Australia’s second airline at the time.

Southern Cross Consortium went big with its pitch: $5.6 billion, believed to be $600 million higher than the next highest bid, joltingly so after a period when it had been publicly trying to talk the price down. In June 2002, Macquarie and its partners were named the winning bidders, securing a 99-year lease in what then finance minister Nick Minchin called “the biggest government trade sale in Australian history”.

It was a day of internal celebration. Macquarie had thrown everything at getting the bid ready and watertight and Moore still looks back on it with pride as an illustration of the bank’s application of maximum possible resources to a task. “Here [1 Martin Place] is where we did the bid,” he says. “We had like 60 to 100 people in the bidroom. We left no stone unturned.”

But that day was also, in the words of one who worked in investor relations, “the beginning of the end for about five years. I remember 2002 as a terrible year, our annus horribilis.”

Why? It started with a perception that Macquarie had overpaid – which, with the benefit of hindsight, is the easiest complaint to debunk. Twenty years later, and long after Macquarie had moved on, the airport would sell again for $23.6 billion (this time with Macquarie advising the buyer). But this overpayment idea was accepted as an unarguable truth in commentary of the time, and that was problematic.

The noise around the deal was amplified by a matter of timing: the fact that just three weeks after the federal government announced the winning Sydney Airport bid, Macquarie announced an $842 million deal to acquire a stake in the concessions to run Rome Airport. The threat of war in Iraq was growing; in October 2002 came the Bali bombings, targeted clearly at Australian tourists. Both impacted the outlook for aviation and therefore the fund’s share price. It would get worse before it got better, with the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus occupying headlines through 2003. “That first year effectively meant Sydney Airport had zero international traffic, which drives 75 per cent of revenue,” says Kerrie Mather, the airport’s CEO from 2011-17.

Macquarie’s share price fell, too: from $41 in September 2001 to $25 in August 2002. Moreover, there was growing concern about the fees going from funds to other parts of Macquarie, and what was perceived as a lack of transparency.

Then there was the brawl with Virgin. At the heart of this was a claim that there was an agreement Virgin would be able to take over the terminals previously used by Ansett, which went into administration in 2001 and ceased operations in March 2002. After the privatisation, Virgin Blue’s co-owner Patrick Corporation claimed, the circumstances of this deal – both in terms of the number of gates and the duration of the access – were changed. “This is turning into a public policy disaster,” Patrick CEO Chris Corrigan told the ABC in July 2002. “You’ve got a privatised monopoly and now you’ve got a private owner, who clearly has paid too much for the airport, who’s now trying to find new and improved ways of gouging money out of the public. You know you’ve got a parking toll, you’re going to have a terminal toll, you’ve got landing tolls already, they’re talking about baggage tolls. Soon there’ll be a toll on a cup of coffee out there.”

At this point Branson was unleashed, the billboards started appearing, and the planes started landing with mockery on their fuselages. When Macquarie Airports had to hold an emergency general meeting to get approval for the capital raise, staff and shareholders came out of the meeting to find a load of Virgin flight attendants with super-soakers. (Macquarie AGMs would go on to become a handy forum for entertaining dissent; one year the hosts of the satirical TV show The Chaser turned up at an AGM with a portable toll gate and started telling people they were charging $3 for access to the meeting that would go “directly into the directors’ bonuses”.)

The Branson matter would be resolved later in typically theatrical style with a preposterous performance outside an airport terminal in November 2002, in which he dressed up in a native American head-dress accompanied by women dressed as Pocahontas and buried a hatchet in front of the T2 terminal.

Moore went through a bruising encounter with Alan Jones after telling the AFR in June 2002: “I don’t think anyone really cares what he thinks.” Jones certainly cared, and set about intensifying his attacks on the bank; Moss intervened, took out an apology to Jones in the same edition of the AFR that Moore’s comments appeared, and reportedly went to Jones’ Circular Quay apartment in Sydney to hand him a written apology from Moore. Moore gave another interview to the AFR a week later in a notably different frame of mind. “We’ve never said we are infallible,” he said. Warwick Smith, who had responsibility for smoothing over some of the bad press, says: “We made a bit of a rod for our own back during that period.” Moore, he says, “learned the biggest lesson of his life. I know the good and the bad of the Alan Joneses of this world, but he was powerful and he was quite unique.”

Eventually it reached the point where anything that happened at the airport – parking, flight delays – was seen as the direct responsibility of Macquarie. And this spoke to a tricky disconnect between investors, who want the fees to go up, and users of the public assets, who want the reverse. “We definitely had a press problem,” says Moss now. “But there was no statistical relationship between the bad press and our business performance. It was invisible in all our metrics except the share price of the affected funds.” This is true: the total annualised return of Macquarie Airports from the time of the Sydney Airport acquisition to the fund’s later internalisation was 12.6 per cent, outperforming the S&P ASX 200 by 5.6 per cent per year.

So what, ultimately, was it about? “I think, in Australia, there was a bit of a cultural cringe, particularly around the airport,” says Moss. By this he appears to mean that, with Macquarie up against the best and biggest investment banks in the world, for Macquarie to have won it must have paid too much. He describes the situations with Jones, Corrigan and Virgin as “really unpleasant stoushes” and says it was “really distracting for quite a few of our staff.” Moss went around speaking to people, division by division, explaining why it was a good deal, why Macquarie was confident.

There was another consideration: that retail investors were just not the right owners for long-dated and illiquid infrastructure assets. Shemara Wikramanayake, a rising name in infrastructure at the time and today the CEO, can see it clearly now. “It was the wrong pool of investors for the asset class – unless they have specialist advice on their capacity to tolerate illiquidity,” Wikramanayake says. “And that was a lesson the whole industry learnt. The market evolves, and our large portfolio of unlisted funds better meets the expectations investors have.”

This is an edited extract from The Millionaires’ Factory by Joyce Moullakis and Chris Wright (Allen & Unwin, $36.99), out this Tuesday

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout