How Joe Hockey rewrote the rules of diplomacy in Washington

How to deal with a US president who’s torn up the rule book? Joe Hockey found the answer.

Joe Hockey’s main course had just been served at Cafe Milano in Washington’s historic Georgetown when two phones at his table rang at the same time. One belonged to Hockey, Australia’s ambassador to the United States, the other to his dinner companion, Republican congressman Devin Nunes, then chairman of the US House Intelligence Committee.

They were both being called about the same explosive breaking news. The Washington Post had just revealed details of the disastrous telephone call between Donald Trump and Malcolm Turnbull in which Trump had berated Australia’s then prime minister over the refugee deal he had struck with former president Obama, accusing him of wanting to export “the next Boston bombers” to the US.

The Post’s front-page account of the phone call exposed to the world a major rift in the Australia-US relationship barely two weeks into Trump’s presidency. Both Hockey and Nunes jumped up from the table and walked outside to make some urgent calls to try to understand how this conversation became public. “So Devin ends his call and walks up to me and says, ‘Did you guys [Australia] leak it?’ ” recalls Hockey. “I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And Devin says, ‘The White House thinks you leaked it.’ I just said, ‘Mate, why would we leak something like that?’”

Suddenly, Hockey was facing the perfect storm — not only was the leak itself hugely damaging, but now Trump’s team seemed ready to blame Australia for it. “We were facing a situation where the White House didn’t know who the enemy was and we had to prevent the White House from getting up a narrative that it was us, because it wasn’t,” recalls Hockey. So he urgently arranged a meeting at the White House with the president’s then chief of staff Reince Priebus and then senior adviser Steve Bannon to assure them that Australia was not behind the story and to explain the importance of the alliance.

As soon as Hockey walked into the meeting, Bannon was on the attack. “Bannon started hostile because the refugee deal [for the US to accept refugees from Nauru and Manus Island] was completely counter-narrative to President Trump’s election policy on immigration,” says Hockey.

As Australia’s most important alliance wobbled precariously in front of him that day in January 2017, Hockey could see that even America’s closest allies were starting from scratch with this new and unconventional president. The shared battles of the world wars, Vietnam and Afghanistan did not ring loudly in the Trump White House. The past was the past and the credits of history did not automatically accrue. The future was transactional and would need to be earned. “If the president saw us as a problem, we had no idea how it would affect intelligence sharing or business or investment,” he says. “From my perspective, the only answer was to develop personal relationships inside this White House and not curl up in the corner and sulk.”

Two and a half years on, Hockey is striding outon an early morning walk in Denver with Colorado’s snow-capped Rocky Mountains floating on a distant horizon. He is pondering the simple question of whether being Australia’s ambassador to the US in the era of Trump has been the best job he has ever had. Hockey flicks through the competition: federal treasurer; minister for employment and workplace relations; minister for human services; minister for small business and tourism. Almost 20 years in federal parliament as the member for North Sydney. “That’s a hard question,” he says finally. “I loved being treasurer but not all the members of the team were on the same team. In this job it’s just been one team, Team Australia. It’s been an extraordinary job to have in Trump’s Washington,” he says, shaking his head. “Just extraordinary.’

The Weekend Australian Magazine spent a week on the road with Hockey as he travelled across the US meeting politicians and mayors, Republican and Democrat donors, prominent Australians and American business leaders. It is the less publicised part of an ambassador’s role: making high-level contacts outside the capital, networking, promoting Australia, leveraging influence and bartering for access to power.

Hockey revels in such trips, partly because they suit his gregarious personality and partly because it gets him away from the hothouse of Washington. His life in the capital is easier now that he has forged a relationship with Trump and a close friendship with the president’s acting chief of staff Mick Mulvaney — a rare feat for a foreign ambassador. But Hockey has faced a torrid tenure in the country’s most important diplomatic post dealing with a series of crises that have flowed from Trump’s unconventional leadership.

The first came in the aftermath of that fractious call between Trump and Turnbull, a call that Hockey says left Turnbull “quite shaken” even though he stood up to the president by insisting the refugee deal be honoured. When news of Trump’s open hostility towards Turnbull was revealed by the Post, Hockey found himself the conduit for a spontaneous outpouring of anger from members of Congress upset about what they saw as the shabby treatment of a close ally.

“The next day I was in the car between the Hilton hotel and the embassy when [Senator] John McCain called me,” recalls Hockey. “He was on a mission. He said, ‘Joe this is outrageous. I’m going to put out a statement that I’ve spoken to you and I fought with Australians in Vietnam and he can’t treat Australia like this and the president is wrong.’ I said, ‘Please don’t do that, John’ and he replied, “Ambassador, I am ignoring your pleas.’

“That day I got 65 phone calls from everyone from [Democrats] Nancy Pelosi to Dianne Feinstein and Republican senators as well,” says Hockey. Although both countries tried to play down the damage caused by the phone call, Hockey admits “it was not good” and for a while it was unclear how Trump would react to Turnbull in the future. A circuit-breaker was needed.

Hockey began plotting with John Berry, a former US ambassador to Australia and current president of the American Australian Association. “We had the friction of the phone call and Joe’s interest was how we heal the rift,” says Berry. Berry’s AAA was holding a gala 75th anniversary function to commemorate the Battle of the Coral Sea on the decommissioned aircraft carrier Intrepid on New York’s Hudson River in May 2017. “We both agreed that this might be the perfect place to educate the president on the importance of the relationship and to get beyond the phone call,” says Berry.

Hockey persuaded Trump’s chief of staff Priebus that the president should attend, and then joined forces with Berry to craft a show designed to dazzle Trump. This included making an emotional video to be screened that night which highlighted 100 years of shared military campaigns by the two countries. “We had every bit of firepower we could find,’ says Hockey. “We had Rupert Murdoch introducing the president, Greg Norman speaking, Anthony Pratt announcing a major billion-dollar plant and [then US Pacific commander] Admiral Harry Harris giving an incredible speech.”

Trump almost missed the night because he was delayed in Washington but he eventually arrived and had an amicable meeting with Turnbull, setting the basis for an eventual friendship. “It redefined in Trump’s mind the relationship,” says Hockey. “He wasn’t familiar with the whole history of the Coral Sea and he had all these voices in the room, voices he respects, telling him how important this relationship was. It was as if there was never any phone call — they both wanted to start again, and having Lucy and Melania there was hugely important also. It was the beginning of a friendship.”

Says Berry: “If I didn’t love Joe Hockey before that event, I loved him afterwards. I saw him bring all of his skill set to bear and help bring about a great victory.”

On a Los Angeles freeway Hockey is flicking through notes about his next meeting, with Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti, a fast rising Democrat who may one day run for president. “The way it is in America is that if you don’t come with something to these sorts of meetings you won’t get another meeting,” he says. Garcetti is interested in ways to generate new infrastructure for his city and wants to talk with Hockey about the asset recycling scheme he pursued when he was treasurer. Hockey wants to hear Garcetti’s take on US politics and particularly the inside story of the Democrat candidates vying to take on Trump next year. This bartering of information is the bread and butter of the job. But picking the powerbrokers in Washington who have Trump’s ear has not been easy.

Hockey arrived in the capital to take over from Kim Beazley in January 2016 and watched the rise of Trump as he became the Republican Party nominee and then president. Trump’s victory, says Hockey, required “a rebirth of the art of diplomacy” from every foreign diplomat in Washington seeking to influence the president and his administration. “There was an established process for gathering information under president Obama because his government was very structural, very procedural and very predictable,” he says. “And then along comes President Trump and all the normal processes are shredded because it is an unconventional administration. You have to have personal relationships because the decisions are being made within such a small circle of people.”

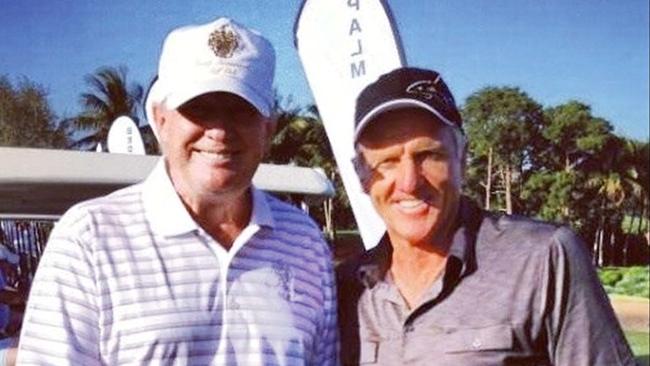

Hockey realised earlier than some other foreign ambassadors in Washington that this different world required him to play by different rules. As soon as Trump won the election, Turnbull wanted to congratulate the incoming president but didn’t have his number. So Hockey called up Australian golfer Greg Norman. “I knew there were no protocols in place for the transition of the Trump presidency so I rang Greg and asked if he had Donald Trump’s number,” says Hockey. “So I rang Malcolm back and said, ‘Try this number’ and he got straight through.’ ”

It also helped foster a surprisingly close working relationship between Hockey as ambassador and Turnbull as prime minister. It was surprising mostly because Hockey doesn’t easily forget those who slighted him during his political career. Turnbull angered him in 2015 when, after becoming prime minister, he declined to reappoint Hockey as treasurer — a move that triggered Hockey’s decision to leave politics.

Turnbull appointed Hockey to Washington shortly afterwards amid claims by Labor that he was a “captain’s pick” who had shown little interest in foreign affairs. “When I was prime minister I spoke to Joe [in Washington] constantly, every few days or so,” says Turnbull, who came to rely closely on Hockey’s counsel. “It was a close and collaborative relationship which was very effective. The outcomes I was able to secure from President Trump were almost unique compared to other nations.”

“How is Olivia’s health these days?’ Hockey asks his colleagues in the back seat as he is driven towards the LA suburb of Brentwood where he will formally present Olivia Newton-John with an honour, the Companion of the Order of Australia. It’s a job Hockey has been looking forward to all week. “I grew up with Olivia,” he says. “Didn’t we all?’

We arrive in a sun-drenched front yard to find 40 of Newton-John’s closet friends gathering to watch the 70-year-old singer, actor and cancer survivor receive her medal. She eventually sweeps in, wearing all white and beaming that smile. As Hockey places the medal around her neck, Newton-John shouts “Woohoo!”, throws her hands in the air and takes a bow. Hockey takes the microphone. “You are being recognised by your nation not just because we are proud of you but because you have changed the world,” he says. “You never walk away from any challenge. You are the most optimistic person I have ever met.”

Newton-John warms to Hockey and decides to invite us to dinner with her friends, including Australian songwriter John Farrar (who wrote You’re the One That I Want and Hopelessly Devoted to You from Grease) and British rocker Peter Noone (frontman of the band Herman’s Hermits). In the car on the way home, Hockey shakes his head and chuckles about accidentally ending up at dinner with a childhood idol. “This job is never predictable and it’s never boring,” he says.

It ends a long day that began at dawn when Hockey, dressed in shorts with the US stars and stripes on them, rode a bike along the Pacific Ocean from Santa Monica to Venice Beach where he ended up cycling around homeless people while listening to Australian boy band Human Nature. Later, as he is driven to his first appointment of the day, a meeting with Australian independent record label Future Classic, he asks everyone in the car who the best known Aussie music acts are in the US these days. He then tries to answer his own question: “Keith Urban. Five Seconds of Summer… then… daylight?”

“Who can name me a Keith Urban song?’ He asks. There is silence in the car.

“I’ll text my daughter,” one diplomat replies.

Hockey first pushed his way into Trump’s orbit by touting the asset recycling scheme he introduced as treasurer in 2015. This scheme to fund infrastructure through private/public partnership attracted the attention of the White House, which was looking for ways to fund Trump’s election promise to reform America’s infrastructure.

Once through the doors, Hockey befriended Trump’s then chief economic adviser Gary Cohn, then chief of staff Priebus and then director of budget and management Mick Mulvaney. From that point Hockey has targeted the White House above all else. He has pushed for access to the small and ever-changing group of people who surround the all-powerful president rather than work through the traditional routes of the State Department or defence and intelligence. “I haven’t done the Washington circuit,” says Hockey. “I’m not disparaging of all the events and cocktail parties but I don’t see it as the most useful way I can make Australia’s case when I am competing against 150 other countries.”

John Lee, who was a senior adviser to former foreign minister Julie Bishop, believes Hockey’s unconventional approach was the right one given the “unpredictable and unique” Trump presidency. “We needed someone who could engineer direct access through establishing a personal relationship with Trump and I am sceptical a more conventional ambassador would have done a better job,” he says.

Hockey has not been shy about promoting quirky ideas and leveraging Australian celebrities to woo Washington powerbrokers. When he arrived at the ambassador’s residence in Washington, a 1923 brick mansion called White Oaks, he saw that it had an overgrown grass tennis court. The only grass court in Washington, it had been installed in the early 1990s by a former ambassador and was used at that time by the Kennedy and Bush families, among others. But it had fallen into disrepair and Hockey’s children were using it as a soccer pitch.

One day Hockey mentioned the court to Westfield chief executive Peter Lowy, who offered to pay to restore it. Hockey then launched the restored court at a gala celebration that included senior US political and intelligence leaders and featured Australian tennis legends Rod Laver and Fred Stolle. It is now the focus of functions that have involved commerce secretary Wilbur Ross, Trump economic adviser Larry Kudlow and Mulvaney, among others. “You try to use all the tools you have as an Australian to make connections,” says Hockey.

When Australian IndyCar champion and 2018 Indianapolis 500 winner Will Power was in Washington recently, Hockey held a reception for him and his winning car, knowing it would attract high powered revheads on Capitol Hill as well as business leaders such as auto racing entrepreneur Roger Penske.

Hockey’s signature campaign as ambassador has been called “100 Years of Mateship”. This has been an effort to better educate Americans and Washington powerbrokers about the fact that Australia has fought side-by-side with the US in every major war since the Battle of Hamel in World War I, 100 years ago last year. The concept initially got a lukewarm reception from some in the Department of Foreign Affairs in Canberra who saw it as hokey but in the US it has proved effective, especially with some American decision-makers who did not fully realise the extent of the shared military alliance.

“The ANZAC story doesn’t resonate in the US in the same way as it does in Australia and so Joe was able to use this mateship campaign to put his arm around Americans and say, ‘We’ve been there from the beginning,” says the AAA’s John Berry.

Richard Spencer, secretary of the US Navy, says it has made an impact. “The mateship goes back 100 years as the fact that in every major conflict Australians have been by our side means a tremendous amount to our navy and marine corps,” he tells me. Spencer and Hockey have since struck up a friendship, enjoying barbecues together, including with Spencer’s friend, actor Harrison Ford. “Joe is the consummate ambassador and he is the best spokesperson for Australia that I have met — he exudes Australia,” says Spencer.

Last year, Hockey savoured Australia’s biggest win with the Trump Administration: the President’s decision to exempt Australia from his steel and aluminium tariffs. Canberra had been lobbying hard across the whole of government to persuade Trump and his advisers that it deserved a special exception. A raft of Cabinet ministers joined Hockey in reminding the White House that Australia was America’s closest military and political ally and that it had a sizeable trade deficit with the US and so was not putting US steel workers out of a job. “The more we spoke with the President and the White House the more they realised that Australia was different,” says Hockey.

Yet the White House did not let anyone else know what it was thinking on this key issue until one day, as Hockey watched Trump name Australia as a country that might be given an exemption from the tariffs. “I saw it on TV in my office and I just yelled out ‘YESSS!’’’ Hockey recalls, raising both arms. He doesn’t try to take credit for the decision, saying Turnbull and Trump had nutted it out. Australia was one of only a handful of nations granted an exemption from the tariffs.

Hockey is in a room in Denver, Colorado, one of the fastest-growing business capitals in the US, with 30 Australian company executives. They have come to hear their ambassador’s views about the economy and especially about Trump. Hockey explains to them why he thinks Trump has a solid chance of re-election. “Trump’s going to go to the next election saying, ‘Well, in the last election I promised you I would reduce taxes, I’ve reduced taxes; I promised you I’d appoint conservatives to the Supreme Court, I’ve appointed conservatives to the Supreme Court…’” He continues on this theme, listing all the promises that Trump has kept from his 2016 campaign including boosting military spending, pulling out of the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal and moving the US embassy to Jerusalem, among other things. “Are you getting the picture?” he asks the group finally. “When did you last have a politician saying that?” He adds: “Also, I’ve never seen anyone in my political life define and destroy someone like Donald Trump.”

Hockey’s own relationship with Trump has been forged on the golf course and through his friendship with fellow golfer Mulvaney, now Trump’s acting chief of staff. Hockey has played with Mulvaney and Trump on various courses around Washington and also at Trump’s Florida resort Mar-a-Lago. Hockey won’t say, on or off the record, what conversations he has had with the President. But other sources say Trump once quizzed Hockey on the course about whether he could trust Turnbull. They also claim that in a more recent round of golf, Trump expressed frustration to Hockey about former Australian High Commissioner to the UK Alexander Downer’s role in triggering the Russia investigation. The President kept referring to Downer as “Dowling”.

The issue of Downer and the Russian investigation has been an awkward one for Hockey. The report of special counsel Robert Mueller stated that the Russia investigation was triggered by Downer reporting to the US a meeting he had in London in May 2016 with then Trump aide George Papadopoulos, who told him that Russia had emails about Trump’s opponent Hillary Clinton. Papadopoulos has since made wild accusations that Downer was spying on him in order to establish that the Trump campaign was secretly working with the Russians, something Downer denies. Trump has previously accused Britain’s intelligence agencies of spying on his 2016 election campaign but he has never spoken publicly about what he thinks of Papadopoulos’s spying claims about Downer. “George Papadopoulos is a totally discredited individual,” says Hockey, with barely disguised scorn. “I mean, he went to jail for lying… He has suggested there is some grand conspiracy, which there wasn’t, so it’s just been a management issue for us… The President has got nothing to fear from us.”

Hockey doesn’t write diplomatic cables back to Canberra so his private views are not at risk of being exposed like those of British ambassador Kim Darroch, who recently resigned after a leak of highly critical cables he had written about Trump and the White House. Hockey’s focus on forging relationships with the White House and with the bigger picture of the alliance has meant he has delegated much of the running of the Australian embassy to his deputies. Some in DFAT do not like this hands-off style of management, although former Bishop adviser Lee defends it. “Joe has been criticised by some for not doing more of the behind-the-scenes work that ambassadors also do, like connecting with Congress, connection with all sorts of stakeholders, the heavy lifting of working with lobby groups, all that sort of thing,” he says. “What I would say though is that Joe has happily delegated that to his second in charge. I think Joe knows what he is good at and what he is not good at. Joe knew what his weaknesses were and he delegated those.”

Earlier this year, with some diplomatic wins and strong White House connections in place, Hockey seemed to be in line for an extension of his posting, due to end in January, so that he would remain through next year’s presidential election. The then Labor leader Bill Shorten had told Hockey before the election that he was open to the idea. But in February Labor turned against him after media reports implied that Hockey had inappropriate dealings with the travel company Helloworld, of which he and close friend Andrew Burnes were shareholders. Hockey attended a meeting at the embassy between Helloworld executives and embassy staff about the delivery of travel services after disclosing to his staff his friendship with Burnes and his shareholding. Both Hockey and Burnes strongly denied any conflict of interest, but Labor’s foreign affairs spokesperson Penny Wong used the issue to attack Hockey, making it unlikely that Labor would extend his term if it won office.

In late May, Hockey decided he would not seek an extension to his posting. He claims his decision had nothing to do with the fact that Labor at that time looked likely to win the election. Some close to him disagree. “I think Joe just made the wrong call,” says one. Hockey will be replaced early next year by Arthur Sinodinos, the senator and former adviser to John Howard. Hockey maintains he has had enough and says it’s time to move on to life beyond government. “Until you’ve had the blowtorch to the belly and been on the front page of every paper in Australia you don’t really know what politics is,” he says. “But I’ve always fought for what I think is right and I’d rather fight and at times fail than be a straw in the wind.”

It is election day in Canberra and as dawn breaks over the Australian embassy in Washington, the two television sets flickering on the ground floor show that early counting suggests Scott Morrison is heading for a surprise win. Hockey walks into the room with a broad grin and greets the small gaggle of political tragics from the embassy watching the drama unfold. He grabs a hotdog and a coffee and slumps into a chair. “Well, there you have it,” he says, adding that he told his staff a week ago that Morrison would win.

For the next two hours Hockey is a politician once again, giving a running commentary on the drama unfolding half a world away. “He’s just a terrible person,” he says of one of his former parliamentary colleagues. “I love her,” he says of another. “She makes my skin crawl,” he says of one. Hockey texts the result to the White House with a reminder for Trump to call Morrison to congratulate him ASAP.

On his morning walk in Denver, against the backdrop of the Rocky Mountains, Hockey ponders what comes next. “I’ve got unique skills but I can’t find a unique job to match them,” he laughs. Along with his wife Melissa Babbage, a businesswoman, and their three children, Xavier, Ignatius and Adelaide, he is weighing up whether to stay in the US — most likely in a commercial job in New York — or return to their home in Sydney.

But for Hockey, the end of his ambassadorial term means the end of 26 years of public service. “Mate, it’s been the greatest privilege, the greatest journey,” he says. “I don’t have a single regret. But I am 53, I have another career in me and I don’t want to stop working. I need to keep moving.”

Whatever Hockey does next, it is unlikely to rival the challenge and the adrenalin of holding Australia’s most important diplomatic post with the most maverick and unusual American president in living memory.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout