Keren Lewinsohn was shopping in Melbourne to buy supplies for her upcoming trip to see her family in southern Israel when an alert appeared on her phone. It was at 3.45pm on October 7, and it warned there were rocket attacks near the Kfar Aza kibbutz. It was a message she had seen at times over the years before, so she wasn’t overly alarmed. This kibbutz, where she grew up, and where her family still lived, was just 3km from the north-east border of Gaza; its 800 residents were familiar with seeing the occasional rocket fired by Hamas terrorists fly over them towards targets in Israel.

But 10 minutes later Lewinsohn received a message that made her blood run cold. It said several terrorists had crossed the border, and it warned residents to go to their fortified safe rooms. “I was like, ‘Oh no’ – so I called my mum, but she didn’t immediately answer,” says Lewinsohn, 37.

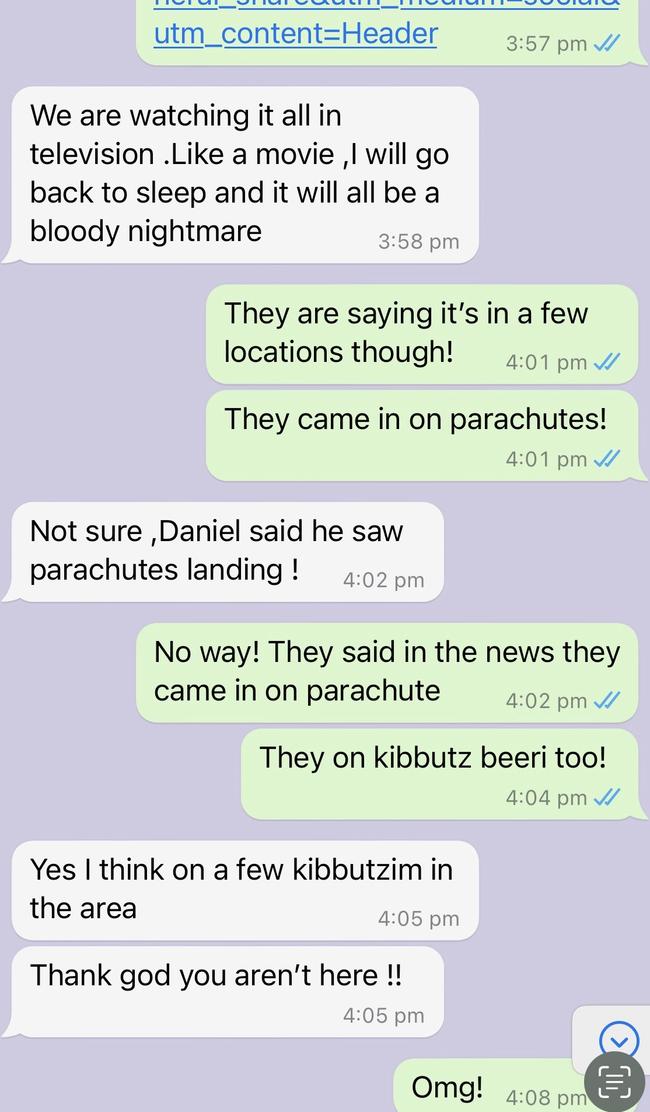

Then she received a message from her mother, Barbara: “Keren we are in the [shelter], so is Alon and family and Michal. We are fine, I even managed to make myself coffee. I will keep you updated.”

Just seven minutes later, at 4.02pm, she received another message from her mother: “Daniel [Lewinsohn’s nephew] said he saw parachutes landing.” Lewinsohn, who was by now watching news of the mass attacks unfold on Israeli news websites, suddenly realised the true horror of what was unfolding. “No way! They said on the news they came in on parachutes,” she replied. Her mum texted back: “Thank God you aren’t here.”

For the next 16 hours, Lewinsohn sat on her couch exchanging increasingly desperate and horrific messages of survival and death on her group family chat, which included her mother Barbara and her father Ralph as they sheltered from the terrorists in one house on the kibbutz, plus her brother Alon and his three children who were sheltering in their home nearby and – until her phone battery ran out – her sister Michal who was hiding under the bed in her own house.

“I stayed up all night, clutching my phone and shaking uncontrollably,” says Lewinsohn. “I was helpless, I could only pray for their lives while all their neighbours were being slaughtered around them.”

October 7 has transformed the lives of Australia’s 100,000-strong Jewish community. Just like Americans have a story of where they were when New York’s twin towers fell on September 11, 2001, almost every Jewish person in Australia has a story of watching the events of October 7 unfold in ever-increasing horror. They saw the images of terrified young Israelis at a music festival running through the desert to escape Hamas terrorists who had laid a trap for their mass deaths. Those brave enough to go on social media saw bodies lying in pools of blood in once-peaceful kibbutz communities.

For many, like Lewinsohn, who had relatives and friends in Israel, those chilling hours as they desperately sought to locate their loved ones will forever haunt them. The cold-blooded slaughter of some 1400 Israelis – mostly mums, dads, children and babies, the largest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust – crushed the sense of security for so many Jewish Australians. It destroyed the belief that although they lived in Australia, on the other side of the world from their Jewish homeland, Israel was always there as a safe haven for them, a democratic beacon created by the United Nations after the Holocaust to prevent a repeat of that horror.

It has made them more fearful and less confident about their security not only in the world, but also here at home. Just 48 hours after the massacre, when the Jewish community was at its lowest ebb, cries of “F..k the Jews” and “Gas the Jews” rang out at Sydney’s Opera House as pro-Palestianian protesters burned the Israeli flag to protest against the Opera House being lit up in the blue and white colours of Israel.

This protest took place before Israel had time to respond in any meaningful way to the massacre. It took place before the weeks of Israel’s retaliatory strikes on Hamas and before the horrific civilian death toll in Gaza. It occurred before the current international debate over how Israel is prosecuting its war on Hamas.

The protest outside the Opera House on October 9 was instead a public celebration of Hamas’s murderous slaughter of innocent Israeli civilians. It was not a protest about the policies of the right-wing Israeli government of Benjamin Netanyahu – it was an attack on Jews because they were Jews.

As one Islamic leader, Sheik Ibrahim Dadoun, told a cheering crowd in Sydney’s Lakemba the night before the Opera House protest as the death toll from the Hamas attack continued to soar: “I’m smiling and I’m happy. I’m elated ... It’s a day of courage. It’s a day of pride. It’s a day of victory. This is the day we’ve been waiting for!”

On October 8, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese released a statement saying: “Australia stands with our friend Israel in this time. We condemn the indiscriminate and abhorrent attacks by Hamas on Israel, its cities and civilians.”

On his Facebook page, Sheik Dadoun responded: “This is an appalling statement. Coward. You were a supporter of Palestine until you were bought.”

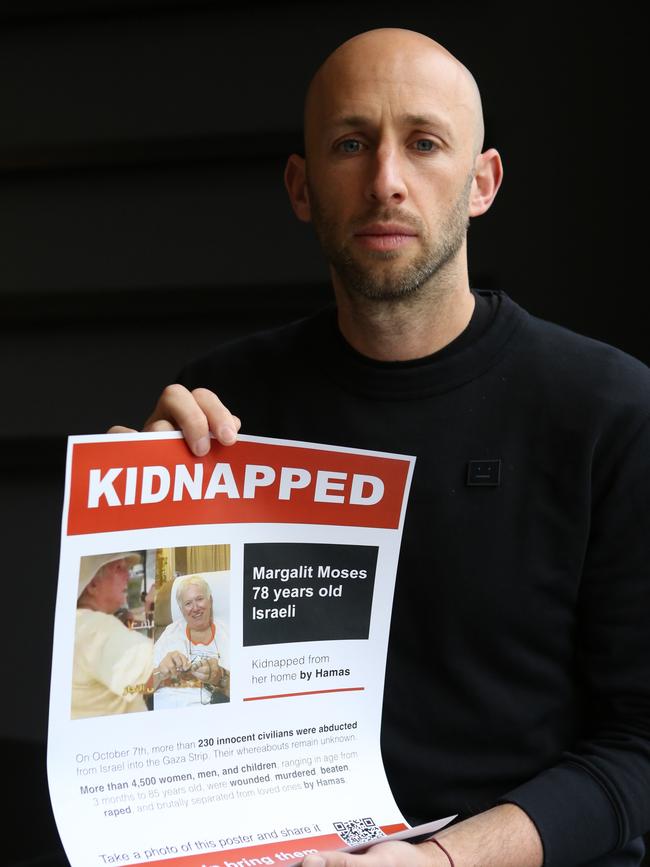

“Our blood wasn’t even dry when that [Opera House] protest was held,” says Dan Monheit, 42, a Melbourne father of two whose father’s first cousin Margalit Moses, 78, was taken hostage and is currently missing in Gaza. “It has broken me. You feel heartbroken, you feel despondent, you feel outraged, you feel hopeless, you feel everything.

“You realise how much it [anti-Semitism] exists and that these people walk amongst us. As Jews you know that it exists but it’s mostly a dull hum that you try to ignore. You get used to walking your seven-year-old daughter past armed guards to go to school every day or to a synagogue, but you can’t ignore what has happened now. It’s everywhere.

“We need somewhere like Israel so that the Holocaust can never happen again. It is meant to be this safe haven where Jews can just be Jewish and ... contribute to the world. We always had the idea that even if Australia became unsafe you could ‘pull the ripcord’ and find security in Israel. We had this innocent belief that as a community we could have a peaceful existence somewhere, either in Australia or in Israel. But that has been shattered. We are not safe anywhere.”

On the afternoon of October 7, Moran Dvir, a 47-year-old mother of four, was driving home from a lunch in St Kilda, Melbourne, when her 19-year-old daughter showed her pictures on her phone of Hamas gunmen in utes driving through southern Israel.

She drove straight to the home of her parents, Avri and Michal, because they had Israeli TV. “We just sat and watched in absolute disbelief,” she says, recalling how the Israeli media reported the unfolding atrocities. “I said to my Mum, ‘Thank God my grandmother [a Holocaust survivor] is not alive to see this’ because we all grew up with the mantra ‘Never again, never again’.”

As her father Avri stared at the screen he said it reminded him of the Yom Kippur war in 1973, when he was a young paratrooper on the front line fighting to defend Israel against a surprise attack by its Arab neighbours.

Like so many Jewish Australians, it wasn’t long before this family realised that, despite living on the other side of the world, their own circle of friends had not been spared. Tears well in Dvir’s eyes as she tells how a former school friend discovered that her brother and niece had been murdered by Hamas while her mother’s body was found ten days later.

“Then our own family was struck – the body of the 23-year-old son of my father’s cousin, missing for a week after the rave, was formally identified,” she says. Dvir called another cousin, Naama. “She tells me about her day, so surreal it wouldn’t even be in a movie. In the morning she visits a bereaved friend who is mourning her son Yoni, murdered at the rave. Then on to the funeral of a friend, Eva. And in the afternoon another funeral, of her mother’s friend, murdered at Kibbutz Be’eri. She thought she would run out of tears. She didn’t.

“It has shaken our sense of safety – physically, psychologically and spiritually. We never thought we would see those images and then we never thought we would hear some very loud voices justifying it.”

Dvir adds: “There is life before October 7 but I do not yet know what life after October 7 will mean. After October 7 nearly every waking moment is filled with a deep ache inside, a constant gnawing grief. It is like being in a waking nightmare with every day worse than the last. The future of Israel and the Jewish people around the world has never felt more uncertain.”

She has been dismayed by what she believes is the selective silence of so many in Australia about October 7. “Across women’s organisations and women’s media outlets I consume regularly, the so-called champions of women’s rights and campaigners of violence against women, there was silence. I contacted the CEO of a global children’s charity we had long supported who had tweeted only about the tragic suffering of the children in Gaza,” she says. “And when I saw the protest at the Opera House I was just in disbelief, and they told the Jewish community in Sydney to stay home.”

Dvir says there is suffering on all sides. “Palestinians need to be freed but they need to be freed from Hamas and I really wish all the energy that has been mobilised against Israel to ‘free Palestine’ was actually used in a way that did free them from Hamas and give them the better life that they, and every human, deserves.”

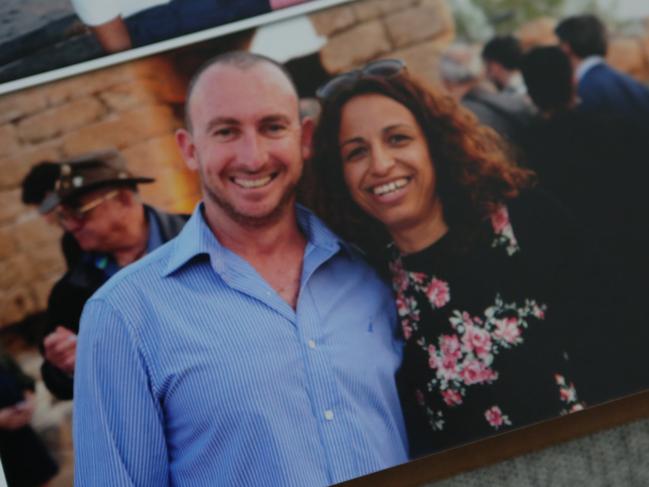

Dan Monheit and his wife, who have family scattered across Israel, watched in horror as the attacks unfolded on October 7 and called up their extended family to make sure everyone was OK. “They were shaken up and traumatised by what had happened but they all were safe,” he recalls. “But then 24 hours later I called and they said things were not good. They said, ‘We’ve just heard that [Dad’s cousin] Margalit and her ex-husband have both been abducted and taken away by Hamas.’ We have a photo of her on a golf cart being taken away to Gaza by Hamas militants.”

The family heard nothing more of them until October 22 when Hamas released two elderly Israeli female hostages. One of those released, Nurit Cooper, 79, shared a cell with Margalit and told Monheit’s family she was “fine” and was “taking care of everyone in her cell”.

“It was a miracle to me that she was alive,” Monheit says. “She is a tough one, I wouldn’t count her out.”

Since October 7, the intensity of Israel’s attacks on Hamas targets in Gaza and the civilian casualty rate that this has caused has seen international criticism of Israel grow. Many in the Jewish community are in anguish about this. They say the world has forgotten that 1400 Israeli citizens were slaughtered just a month ago, and that Israel is now being wrongly criticised for enacting its right to defend itself to ensure it is never attacked like that by Hamas again. They ask, can you imagine if the US was told after 9/11 that it could not hunt down the leaders of Al-Qaeda, or Australians were told after the 2002 Bali bombings that they could not hunt down the Bali bombers?

Palestinian supporters retort that two wrongs don’t make a right, and that Israel’s retaliatory bombing of Gaza – which has left many thousands dead – is a disproportionate reaction that amounts to collective punishment of the civilian population for the actions of Hamas. But the dark side of this legitimate political debate is that the dividing line between Israeli politics and the Jewish religion has become increasingly blurred. Regardless of people’s opinion on the rights and wrongs of Israel’s military response to October 7, the disturbing fact is that many Australian Jews are being targeted not because of their political beliefs, but simply because they are Jewish.

“I think we’ve certainly seen some of the protests as well as commentary and discussion on this conflict veer quite strongly into antisemitism,’ says Dave Sharma, Australia’s former ambassador to Israel. “The Opera House protests took place when there were still towns and communities in Israel under siege by Hamas gunmen and Israel had not responded. So the only way you can interpret that was that they were celebrating or glorifying the Hamas attack.”

Sharma says there has been a failure by many pro-Palestinian protesters to distinguish between the political actions of Israel and Jewish Australians. “We’ve seen Jewish people collectively held responsible for the actions of the state of Israel, which is Jewish in character, but it is textbook antisemitism to say that the Jews as a religion or ethnicity are responsible for the actions of the state of Israel. That distinction has been entirely blurred.”

As the minutes ticked away on October 7, Keren Lewinsohn sat in her Caulfield home messaging her family every 15 minutes for updates while they hid in their homes as terrorists roamed the Kfar Aza kibbutz.

“My parents told me that they could hear gunfire and explosions and people running around speaking in Arabic and yelling Allahu Akbar [God is great],” she recalls.

“At 5.36pm I received another message from my mum telling me that apparently there are some casualties on the kibbutz,” says Lewinsohn. “I was lost for words, but this was only the beginning of the mass slaughter that was going on around them.”

Through other WhatsApp messages, neighbours swapped rumours about who had been attacked and killed, where the terrorists were, and asking: where was the Israeli army?

Lewinsohn lost contact with her sister Michal for 12 hours when her phone went flat. One of the last messages her brother sent Michal was: “Don’t make any moves. Stay as quiet as possible.”

For several hours Lewinsohn said she thought Michal was dead. “My parents were hearing messages that the area where my sister was living was a complete bloodbath. I just sat there and sobbed.”

At 12.29am Melbourne time – more than eight hours after the terrorists entered the kibbutz – the killings were still taking place.

From her safe room her mum Barbara messaged Lewinsohn’s brother Alon in his house: “Are there terrorists around you?”

“Seems like it,” he replied.

A desperate Lewinsohn in Caulfield messaged them: “Where is the f..king army?”

Barbara replied: “Where the hell is God. Just want my children and grandchildren to be safe.”

Then, at 10am on October 8, Lewinsohn finally got the miracle she had been praying for. Her parents and her brother had been rescued by the army and they had found her sister alive. “It was like angels were standing over my family,” says Lewinsohn.

When Lewinsohn’s parents emerged from their home, they confronted an apocalyptic scene of the bodies of dead neighbours and dead terrorists strewn on the streets. Houses had been burned down or damaged by grenades. It was a scene of utter devastation.

“Mothers, fathers, babies, young families killed in their beds, in the protection room, in the dining room, in their garden,” Israeli Major General Itai Veruv said after going door-to-door to collect the bodies in the kibbutz. “It’s not a war, it’s not a battlefield. It’s a massacre,” Veruv said. Some victims were decapitated, he added. “I’ve never seen anything like this, and I’ve served for 40 years.”

Some 58 residents of Kfar Aza lay dead, with 17 kidnapped by Hamas and several still unaccounted for.

Soon Lewinsohn heard the worst possible news about the families and friends she had grown up with on the kibbutz. Her nephew Daniel’s best friend Tomer, aged just 17, was kidnapped and forced to walk from house to house calling on people to come out of the bomb shelter – and when they did the terrorists shot them, filming their death on social media. Eventually the terrorists shot him dead also.

Lewinsohn’s childhood friend Yahav, who she once visited Australia with, gave his life for his family when he pushed the terrorists back as they tried to enter his house through the bedroom window, giving his wife Shaylee time to flee across the fields with their four-week-old daughter Shaya. “Yahav saved Shaylee and Shaya’s life,” says Lewinsohn.

Her closest family friend Tal Eilon, who had been to her wedding and who lived across the road from her parents, had been shot dead.

Another family friend, Smadar, and her husband were killed; two of their children – Michal, nine, and Amalia, six, hid in a cupboard for ten hours before they were rescued. The couple’s third child, Abigail, four, who was covered in her father’s blood, was seen running away from the house by a neighbour who picked her up and took her into his bomb shelter with his wife and three children. All were later discovered by Hamas, and were taken to Gaza as hostages.

Lewinsohn says her family is still struggling from the loss of their Israeli community. “We are still having funerals for friends of our kibbutz whose bodies were only recently identified or found,” her father Ralph wrote recently. At one stage she said her parents had so many funerals on each day, they had to choose which ones to attend.

The irony, she says, is that her parents and many others in the politically progressive community at Kfar Aza were sympathetic to the difficult life of people in Gaza and were involved in driving sick Palestinians from the Gaza border crossing to Israeli hospitals for treatment under a charity program called Road to Recovery.

Lewinsohn takes out a photo album from her recent visits to Kfar Aza and flips through it, pointing out her friends. “He’s dead ... she was injured ... she escaped ... they survived,” she says as she turns the pages.

Julian Cappe heard them coming before he saw them. Hundreds of demonstrators, some wrapped in the Palestinian flag, aggressively chanting antisemitic slogans and marching past him to the Opera House. Cappe, a father of three, was waiting for his ferry at Circular Quay, and was harbouring his own personal distress. His beloved Australian-born cousin, Galit Carbone, was missing and feared dead after the devastating attack by Hamas on the Be’eri Kibbutz near the Gaza border.

Then he was confronted by a sight that he never imagined he would see in modern Australia, especially outside its most famous landmark. “There was this vicious, aggressive chanting of genocidal slogans such as ‘Gas the Jews’ and ‘From the river to the sea’ – which is a literal call for driving out Jews from their homes in Israel,” he says.

“This was immediately after the brutal slaughter of our friends and family in Israel in a literal modern-day pogrom, and prior to Israel taking any action in response, and already there was a mob in the city calling for actual genocide against Jews.”

Lewinsohn agrees. She says that when she heard the chants outside the Opera House two days after her family’s trauma, she just shook her head. “It reminded us how much antisemitism was out there and the attack by Hamas just made it more prominent,” she says.

The Opera House demonstration was widely and quickly condemned, with Albanese describing it as “horrific”, “antisemitic” and “appalling”, while NSW Premier Chris Minns described the scenes as “abhorrent”. The fact that the Jewish community were warned by police to stay away while the protest was allowed to continue only added insult to injury.

Former federal Treasurer and prominent Jewish community member Josh Frydenberg said in a speech shortly afterwards: “I stand before you anguished and anxious about the future. When hundreds of demonstrators in Sydney chant ‘F..k the Jews’ and ‘Gas the Jews’ we know just how dangerous and serious that problem really is. What happened outside the Sydney Opera House was nothing short of an abomination. A national disgrace that has become an international embarrassment.”

Authorities feared that the Opera House protest had helped to light the fuse for a surge in antisemitism. Albanese quickly met with Jewish community members in Melbourne, saying: “Many of you will fear a rise of antisemitism at home. I want to assure you that kind of hateful prejudice has no place in Australia.”

The next day Mike Burgess, chief of the domestic spy agency ASIO, warned of the potential for “opportunistic violence” and called on “all parties” to refrain from stoking division. “Words matter [and] ASIO has seen direct connections between inflamed language and inflamed community tensions,” he said.

But their words have done little to halt a rising tide of antisemitism in Australia and around the world. According to the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, in the week before October 7 there was just one incident of violent antisemitism reported in Australia. In the week after there were 38 incidents, in the second week 27, and by the end of the third week another 32.

As Julian Cappe’s ferry took him past the frightening scenes at the Opera House he still had some hope that his cousin Galit, a 66-year-old grandmother, was still alive. But the following morning, Cappe finally received the news he had been dreading. His cousin’s body had been discovered amongst many others on the Be’eri Kibbutz. She was the only Australian victim of the October 7 attacks.

“It was a terrible, terrible personal shock that we all felt very deeply,” he says. “She was so connected to her family and to the tight-knit community on the kibbutz,” he says.

Cappe says that when news first broke of the attacks on October 7, he frantically messaged his cousins on the kibbutz. “I finally made contact with one of my cousins who was still in hiding while the terrorists were rampaging over the kibbutz committing atrocities. She told us there was gunfire and screams outside, and she knew that her friends and neighbours were being massacred. The terrorists were setting fire to buildings to drive out people from their hiding places. Later we learned they were killing children, babies, old people, everyone.”

Cappe’s wife Lisa says they later learned how the terrorists had burned people alive, including children. “They forced parents to watch their babies being burned,” she says about what unfolded on the kibbutz. “There were groups of children who were tied up together and then burned alive. The terrorists were inflicting as much pain and brutality as they possibly could.”

At least 120 people were killed at Be’eri, or one tenth of its 1200-strong community, and many others kidnapped.

Julian Cappe says the massacre and the immediate surge in antisemitic rhetoric both in Australia and globally, including on social media, has given the Jewish community in Australia a deep sense of anxiety.

“It feels that many of those who have made a point of standing up and supporting vulnerable groups have not shown their support for the Jewish community in our time of need,” he says. “We have a deep sense of our history, and it is with deep foreboding that we feel the historical scourge of hatred against our people has returned to the mainstream.”

Moran Dvir says that she and her Jewish friends are also “nursing our heartbreak in the face of antisemitism playing out daily in all spheres of our lives here in Australia. It feels like whack-a-mole on repeat.”

Joe Szwarcberg, 93, was watching television in his Caulfield home on the night of October 7, trying to digest the indigestible horror of what was unfolding in Israel. Szwarcberg says his mind could not help but delve back into his sepia-toned past, when he was torn away from his family by the Nazis and thrown into a concentration camp in Poland in 1942.

He was 12 years old. The Germans killed his father and mother and shot his brother in front of him. The American army found him at Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany when the war ended, and at the age of just 17 he emigrated to Melbourne, knowing nobody. He eventually married, ran a shoe shop in Bentleigh for 58 years and now has two children, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

“When I saw what those terrorists were doing to those young people at that festival and in the kibbutzes I just, I just really could not believe it,” he says, shaking his head. “I mean, it sent me back to what I went through when I was a child. It brought back lots of very dark memories.”

Szwarcberg said he was just as dismayed two nights later when he saw the demonstration outside the Opera House. “I was completely horrified and shocked. I am watching the television hearing people in Australia say ‘Gas the Jews’ and ‘Kill the Jews’.

“As a Holocaust survivor I just broke down. I could not sleep for the next few nights. I just kept thinking that there are people in Australia, the country I came to so that I could have a safe life, who want to kill Jews.

“Once a week, I go to the Holocaust Museum and I speak with schoolchildren about my life story. Why do I do that? Because I want to help to make sure that things like that never happen again. But now I can honestly say that I am frightened. I am frightened for my own children, for my own family. I am frightened because it feels as if it could happen again.”