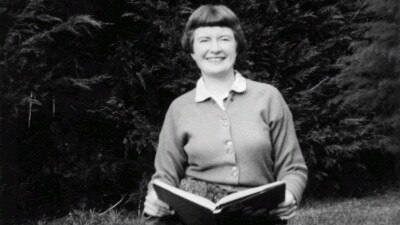

How Gwen Harwood found her freedom in poetry

She was a trickster-poet who created mischief and challenged convention. And when Gwen Harwood found her voice, Australian poetry would never be the same.

Gwen Harwood took great interest in the writing of her biography. In general, she was wary of literary scholars; having people pontificate about her in print made her feel like “peaches being put in a tin & the lid soldered on”. But when it seemed, in the early 1990s, that more than one biographer had taken on the task of writing her life story, she was pleased. With two different versions of her life in circulation, she might slip out between them. There would be room to manoeuvre, an elusive in-between space for her to occupy.

For a time, she encouraged both would-be biographers to believe that he or she alone was her “official” choice, sending them off to hunt down her letters and speak to old friends. In her mind, the book to be written by her long-time friend and Harwood scholar Alison Hoddinott would be a “sensitive” literary biography, while the one by young medievalist Gregory Kratzmann would “dish the dirt”. The would-be biographers found the situation less than ideal, however. When Hoddinott discovered that Harwood had made the same promises to them both, she withdrew, leaving Kratzmann in possession of the field.

Harwood died in 1995, aged 75, before Kratzmann was far into his book, so he decided to publish a volume of her letters instead. This compromise would have pleased her. In place of a biographer’s authoritative tones, her many voices would be on display. She was the trickster-poet after all, an enigmatic figure of wigs and masks. Even as a young woman she hated being confined to a single identity, a single narrative, a single voice. At 22, working as a clerk in the public service in Brisbane and playing the organ at weddings on weekends, she liked to channel a range of personas. “I have three characters – with variations – which I play at weddings,” she told a friend. “The Young Genius, the Soulful Maiden and the Embittered and Disillusioned Musician. Circumstances and singers determine which I am to be.”

A little less than two decades later came the first of the pseudonyms with which she would launch guerrilla raids on the Australian literary establishment. The earnest “Walter Lehmann” was the author of a pair of acrostic sonnets smuggled into The Bulletin – one of which read “F..k all Editors” – that brought the Vice Squad down on that august journal. Even as all hell broke loose, the anguished “Francis Geyer”, a supposed migrant musician from Hungary, continued to sing to his lost love on The Bulletin’s famous Red Page. Most daring of all was the “lovely lady poet” Miriam Stone, who wrote a series of furious, brilliant poems about domestic life. In this guise Harwood was able to say things about women’s experiences that nobody else was – until she was outed by eagle-eyed readers and had to shut Mrs Stone down. The Australian poetry community was in a frenzy. “It was not simply that a new and unsuspected poet of virtuoso technical accomplishment, wit and insight had appeared,” wrote poet Andrew Taylor. “Rather, there seemed to be two of them, or possibly more. Guessing which poems, over different names, in The Bulletin were actually written by Gwen Harwood became a regular game.”

In her private life, Harwood was always alert for moments of crossover between the everyday and the storied realm. As a 1950s housewife, she was “the stately flower of female fortitude”, endlessly capable and good-humoured. As an aspiring poet, she was Burning Sappho, a woman of incandescent gifts, cruelly caged in Hobart suburbia and fighting for her life. Neither role contained her. “I wish I had several lives,” she once sighed. “One for songs, one for poetry, one for being an abandoned alcoholic, one for being a cored and peeled hausfrau, one for beachcombing, one for being an Italian…”

When I began, tentatively, to follow in Hoddinott’s and Kratzmann’s footsteps, trekking around the country to the various repositories of Harwood’s letters and papers, I was dazzled by the playful brilliance of her personal writings. Her letters – of which there are several thousand, many still unpublished – made me laugh aloud. But for all her merriment, it was evident that she often felt painfully trapped. Her letters to her closest friends speak of her restlessness, her impatience, her resentment of a confinement from which she could never quite break free.

Gwen arrived at the tiny airport at Cambridge, just outside Hobart, on a chilly Saturday afternoon in late October 1945. She was overjoyed to find her new husband Bill waiting for her at the airport. A former naval officer, he had secured a job as a lecturer in the tiny English department at the University of Tasmania. They melted into each other’s arms “with good old-fashioned happiness”. Though Hobart’s Georgian buildings and English country gardens were charming, “something about the place [spelt] death to me”, she wrote to a friend. “This was my first feeling when I landed here in 1945: not, ‘How beautiful’ but ‘Get me out of here”.’ This chill island was most definitely not the sunny, relaxed lotus land of her childhood. If Brisbane was a sprawling, brawling, open-air city, Hobart was a stone fortress against the bitter weather.

Gwen and Bill moved to a cottage in Fern Tree, a village halfway up Mount Wellington. Conditions were primitive. By night, possums made a “ghastly racket in the roof” and “bush rats [ran] round [the] bedroom”. By day, the birds descended upon their newly planted vegetable garden. But the newlyweds were happy. Gwen threw herself into domesticity with zeal. She was still glowing with idealism about her new role as wife and helpmeet, and determined to be the embodiment of the perfect housewife. In the evenings, she and Bill sat by the fire reading and talking “endlessly”. When Bill was at work, however, Gwen felt her isolation keenly.

She was delighted to find, early in 1946, that she was pregnant. All went well with the birth, though she would later say that she was “unprepared for the pain, and howled like a Wagnerian soprano”. When she brought baby John home a fortnight later, she was overcome with happiness. “I took him onto the balcony; snow started to fall. I stood with my child in a state of inexpressible joy.”

She loved being a mother but as she and Bill settled in to their new lives, she became aware of the gap between her idealised vision of love and the reality of marriage. This was becoming evident in all kinds of small ways. She was gradually coming to understand that Bill did not enjoy “frolicsome company”, and was “indifferent” to art and music. Less sociable than she, he was also more private. Bill paid for the household, so he could order it as he chose. “I wished I had listened to my mother – her last words as I left Brisbane were, ‘Keep your own bankbook.’ I stupidly didn’t and passed my savings into the common fund.” She very much wanted Bill’s approval, and was alert to any subtle signs that she had disappointed him. She had learned that he conveyed his displeasure with looks and silences – what she dubbed “Bill’s coldness”.

His silences inflamed her fear that if she did not live up to his expectations, he would cease to love her. She was determined not to risk that. If that meant being aloof with others instead of warm and lively, she was prepared to do it. If it meant keeping art and music in the background, she would do that, too. Later, she would say that she lost her “natural shape”, explaining: “When I look back on the early years of our marriage I cannot imagine myself.”

But there was so much that was good in their marriage – in their intellectual companionship, their sex life, their “mutual solicitude” – that such sacrifices seemed a small price to pay.

Gwen did not, however, give up poetry. In Hobart, writing and publishing assumed a new urgency. She would later see these early years as her poetry apprenticeship. With no mentors available she became her own teacher, reading all the contemporary poetry she could get her hands on. She was not entirely on her own in her pursuit of a poetry career. Her friend Ann Jennings was also toying with becoming a writer, and her interest, like Gwen’s, had become more urgent with marriage and motherhood, and the concomitant fear that her independent selfhood would be lost.

Ann’s first impression of Gwen was that she was “too abnormally intelligent and articulate”. She felt that Gwen did not think other people “important enough to concern herself with them”. It would be several more years before Ann would know Gwen well enough to understand that her seeming aloofness was all show; she had the same kind of passion for friendship as Ann. She had simply parked this side of herself, temporarily, in order to emulate her new husband’s tastes and inclinations. One of the people Gwen was most passionate about was Ann herself, whose beauty and life deeply stirred her. She had been drawn to Ann before she even knew who she was, catching sight of her on the bus: “Masses of glorious hair, eyes blazing with experience – 19? Thirty? I couldn’t tell.” But though the two women saw one another often, Ann had no idea how much Gwen liked and admired her. Ann’s attitudes were liberal; she was unencumbered by traditional Christian views of sex as sinful, and keen to expand her sexual experience. She was also ambivalent about motherhood, loving the intimate bond she had with her babies but chafing at the need to sacrifice so much of her own identity to care for them.

Only three of Gwen’s poems have survived from this time – The Dead Gums, The Fire-Scarred Hillside and Water-Music – and all three were published in 1949. The first two are meditations on her new landscape, which she depicts as speaking to her of her own mortality. The third tells the story of Eve in the Garden of Eden, and is livelier and more subversive than the other two. Harwood’s Eve is a mischief-maker who does not so much unleash the world’s darkness as reveal it: its “sweet corrosive core / and the sorrows at its heart”. This poem was accepted by Meanjin in May 1949.

Later that year Bill and Gwen moved to Taroona, a seaside town some 10km from Hobart, where they bought their first home and welcomed their second son, Christopher, with joy. Less than two years later Gwen was pregnant again, with twins, and in early 1952 they moved into a large family home in Lenah Valley. In August their babies Peter and Mary were born. Gwen’s family responsibilities doubled overnight. She had been busy before, but now she was completely submerged in household labour. Some time later, she would reel off a list of domestic woes that stymied her during these years: “the measles, boils, wet beds, fevers, tonsils and their endless endless endless proliferations”, not to mention the babies howling “night after night until I was half-schizo from lack of sleep”. Home sometimes felt like a prison as “spirit beat at flesh as in a grave / from which it could not rise”.

Writing became ever more important to her but she “kept all that out of the way; a secret vice, like drinking with bottles in the wardrobe”. She wrote “while the household slept”, so that neither the children nor Bill could feel that her poetry was taking time and energy that rightly belonged to them. The very desire to write was a kind of betrayal of the full-hearted presence she felt she owed them. And yet ignoring that desire was, she increasingly saw, a betrayal of herself. Why could she not simply be happy as a loving and much-loved wife and mother? Why must she be continually tempted by her dark alter ego, the “savage, nasty part” of her that would sacrifice everything – love, children, home – for a few hours of solitude?

The “Stately Flower”, a phrase borrowed from Tennyson, was Gwen’s term for the domestic saint she felt she was supposed to embody. “Burning Sappho” was her incendiary alter ego, her poet-self who seethed with frustration and flared with rage. The phrase came from Byron’s Don Juan. While the Stately Flower presided with imperturbable calm over all kinds of household disasters, Burning Sappho smouldered. In the early 1960s, she would turn this simmering inner conflict into a series of powerful poems. Lip Service depicts a woman determined to embrace her role as domestic goddess by banishing her inconvenient longing to write. She will be content, she vows, with the life she has, and she will achieve this by the simple stratagem of cutting out her own “core” – removing “the seeds / Of discontent” as she would de-seed an apple. Purged of her bitterness, she will become sweet nourishment for her family, serving herself up to “fill the needs / Of husband and importuning child”. But in the poem’s last stanza, she rebels. Such an act of self-mutilation would be little less than a lobotomy, leaving her unrecognisable to herself, a stranger in the mirror “with an idiot grin”.

Burning Sappho takes the opposite tack, depicting a woman who refuses to give up her deepest ambition no matter how impossible it is. Owing something to Hal Porter’s Brute’s Wife, this poem is full of murderous fantasies. The speaker struggles throughout the day to find a few private moments in which to write, but is thwarted at every turn. “The clothes are washed, the house is clean,” she begins. “I find my pen and start to write.” At once her child “kicks her good / new well-selected toys with spite / around the room, and whines for food”. The woman leaves her work to tend to the toddler, but behind her smile is a “monster” who “sticks her [child’s] image through with pins”.

At last the day is over, and all her tasks are done. She has persevered, and won “this hour” of time for herself. But just as she starts to write, her husband calls her “to bed”: “Now deathless verse, good night. / In my warm thighs a fleshless devil / chops him to bits with hell-cold evil.” It is now too late to do anything for herself. She surrenders to sleep until “Some air of morning stirs afresh / my shaping element”. In the pre-dawn, she seeks her pen: “I’ll find / my truth, my poem, and grasp it yet.”

It was only when Gwen began to realise the warping effects of her efforts “to please others who were indifferent” that she began to give attention to what she would later call “the self that made my tongue my own”. “No one may like the shape I take,” she growled in the 1970s, “but no one is going to espalier me again.” Owning her tongue was about claiming the right not only to speak but also to be silent – even to lie. It was about using her voice as she chose: to hide or to reveal herself, to try out different characters, different truths and possibilities, and to speak the love she felt compelled to own. It was about claiming her sexual freedom, too. Above all, it was about claiming her freedom as a poet. This she did – and Australian poetry would never be the same.

When she claimed the right to find her own shape, she became that rare poet who forges her own style. With her fierce “independence of spirit”, she discovered the gift of communicating her inner life to her readers – thus making her way into theirs. She went on to become, in Peter Porter’s words, a “true master”, the most accomplished Australian poet of her century.

Edited extract from My Tongue is My Own, A Life of Gwen Harwood, by Ann-Marie Priest (La Trobe University Press, $37.99), out May 4.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout