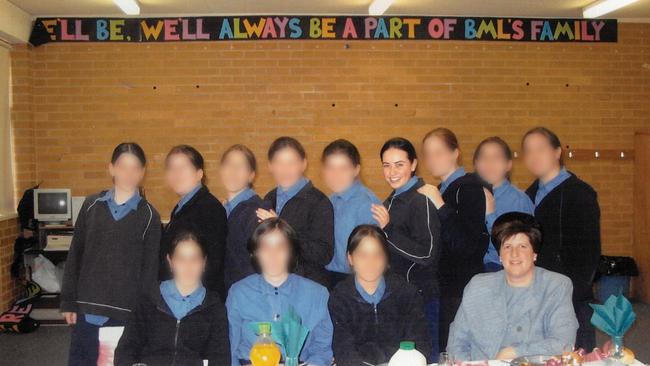

When Dassi Erlich’s parents moved to Australia from England in 1981 they embraced a strict ultra-Orthodox sect known as the Adass Israel Community, hardly recognisable to mainstream Jewry. Dassi Erlich, one of seven children, was enrolled in East St Kilda’s Adass Israel School. Malka Leifer became Principal in 2002.

In February 2003, I entered Year Ten at Adass Israel School. I don’t remember much of that year other than the respect and awe I felt towards our new principal. The girls in my class had begun to talk about whose brother they would be set up with by the matchmaker, and what speaking to a boy would be like, but my head was full of thoughts of Malka Leifer. I thought that if somehow I could become a favourite student of hers, I would be viewed more favourably by the matchmakers.

Marriageability was something we often talked about. Girls in the class above us were getting engaged, and at 16 we knew the eyes of the community were on us. As well as favourites, Mrs Leifer had students she disregarded. I recall her mocking one girl’s mannerisms while the girl had her back turned. I felt nauseous; as I imagined being that girl, I wanted to cry. The possibility of the principal mocking me made my stomach twist. School was the only place I felt safe; I couldn’t bear the idea of this space turning ugly. I was determined to be liked by her, but I didn’t know if I could be likeable. I envisioned asking for her help, and imagined how I would feel if the leader of our school paid attention to me. Me, the girl whose own mother had declared she wasn’t worthy of existing.

One day, Mrs Leifer touched me on the shoulder and called me into her office. I stood beside her, my chin lowered and my eyes turned away. Her voice was close to a whisper. “I know about the situation at home, Dassi. I’m here to support you, like I support [your sister] Nicole.” I was enchanted. The principal wants to support me! I walked out of her office with a straight back and a smile on my face. After that conversation, I purposely walked past her office as often as I could, trying to catch her eye. She would call out to me to run an errand across to the primary school, or once even to go down the street to the boys’ school. My classmates noticed, and that brought its own status. The principal’s special students were worthy of respect.

At some point, I’m not sure when, I confessed to the principal that I wanted to share something I was troubled about. She encouraged me to speak up, but I was so in awe of her, I didn’t share the details. Instead, Mrs Leifer arranged a private phone call with a rabbi’s wife (rebbetzin) she looked up to in Israel. Safe in the knowledge that the rebbetzin lived abroad and didn’t know my family, I was able to confess that my father gave me hugs that were uncomfortable.

The rebbetzin advised me to stay away from my father. I explained that disobedience was heavily punished at home, but she wasn’t listening. I ended the phone call, frustrated that she hadn’t understood me, and was further annoyed when increased attention from Mrs Leifer made me suspect the rebbetzin had shared our conversation. I was terrified of anyone finding out. These more frequent interactions with Mrs Leifer continued through Year Ten.

Before the Jewish high holidays in September, the teachers took a count of which girls would remain in school the following year. Our Year 11 class would shrink to just eight girls, with the rest of the class going to seminaries overseas. The right seminary could lead to a better offer of marriage. The Jewish high holidays are the season of spirituality, and the New Year led into the ten days of repentance, ending with Yom Kippur – a day of atonement and the holiest day of the Jewish year. Repentance, prayer and charity are the themes of the time.

On the last day of the holidays, my mother sat me down and told me I was a girl she could see had an evil inside, unworthy of the effort it would take to send me to seminary. “You’re a pretty face and nothing else,” she reminded me. “Can’t even live up to the virtues of Elly and Nicole.” I searched my mind, trying to figure out what I had done wrong. I had been trying so hard. I knew she was frustrated, and I feared that I would never be able to leave the house. Who would want to marry me?

Don’t let her see how acutely you want her attention, I told myself. I felt pained with my desperation, and panicked Mrs Leifer would see through me to the sin my mother claimed lay within me. Mrs Leifer ended her call and came around her desk to sit beside me. Her presence so close rendered me speechless. She pointed to a religious text and explained that during our private lessons over the summer we would be studying a book on one’s personal Jewish morals. The book was written in Hebrew, with a smattering of Arabic words in every paragraph.

I was asked to read aloud, but when I tried to voice the words, they wouldn’t exit my mouth. I read Hebrew fluently, but the Arabic words were unpronounceable to me. My mind blanked. I am such a stupid, stupid girl. I couldn’t think of the text when she looked at me. I don’t want her to regret choosing me for this privilege. I wanted to disappear. Mrs Leifer moved to put her arm around my shoulder. She stroked my back and my body calmed. I was not used to being touched gently. Her warmth felt loving, and I sank into it. “Let’s forget about this,” she said in a low voice. “Let’s talk about you. How are you feeling?” I couldn’t respond; no words would come. No adult had ever cared how I felt. I didn’t even know how I felt. Most of the time I felt numb. She pushed for an answer, her hand rubbing circles on my back. What do I say? What is the right thing to say? “I don’t know,” I mumbled. My head was down, so I didn’t see her face, but her tone was baffled. “How can you not know how you are?” I was mute. I know there’s something wrong with me; please don’t give up on me.

I had never been a speaker; silence had always been my friend. My parents’ abuse expected silence. Obedience is silent. Silence is safe. Mrs Leifer moved her arm to my knees. Her touch was reassuring; I didn’t want it to stop. Her hand travelled up my thigh, and even with my gaze lowered I could feel her watching me.

Does she realise what she is doing?

Overwhelmed, I kept silent. She continued to move her hand up my thigh.

This is weird, but she is Mrs Leifer; it must be OK.

I didn’t know it then, but this was the start of a pattern, one that would escalate.

All I remember of my engagement party is the slap I received from my mother moments before we went to my future in-laws’ house, where the event was to be held. She was angry that some handwashing was still soaking in the sink. Preparing for my engagement party was not an excuse to not do as I was told. I didn’t cry when my mother hit me anymore, the tears had long left me, but that night I remember them threatening to spill. It was the audacity of it. How dare she slap me just before I celebrated my engagement with the community?

As I looked in the mirror to fix my mascara and cover my red cheek, I whispered to myself, “It’s only a little while until you’re married, Dassi. Just a few more months and then you will be out of her control forever.” The freedom of escaping my childhood home was threatened when my fiancé, Shua, bluntly informed me that he had asked his rabbi if he should break off our engagement. By this time, Shua had seen enough of my mother to know the truth. An abusive home was an additional black mark against my name, and signified I was damaged goods. However, his rabbi told him that a broken engagement would jeopardise future matches. Shua told me all this over a phone call which lasted an hour. I thanked him for not giving up on me, and spent most of the time convincing him I was nothing like my mother.

In some ways, over the next few months my world opened exponentially, but in other ways it stayed exactly the same. Mrs Leifer was still abusing me – preparing me for marriage, she said. These secrets terrified me; I feared that Shua might discover them and deem me unworthy of marriage. My mother’s control became tighter, knowing I would be out of her orbit soon. I was getting Kallah (bridal) lessons from a woman in the community, whose job, now that I was engaged, was to teach me about sex. The laws around sex were long and complicated. My mother found someone who was willing to teach me for a reduced price. I sat in my Kallah teacher’s house and watched as she drew a diagram of a vagina and penis. The idea that I had a vagina absolutely blew my mind. I asked her how I would find it. She instructed me to go home, find a mirror I could stand over and examine myself. Even after I learnt about sex, I couldn’t write the word down in my diary. I left blank lines. When Mrs Leifer touched me “down there” and put her fingers inside me I had assumed it was the same place I urinated from. The understanding that women had two openings there suddenly made so much sense. This is what Mrs Leifer must have meant when she said she was preparing me for marriage. There must be someone who prepares every girl for marriage in that way, I thought.

This is what I found in my diary, likely written shortly after my engagement:

Day ?? of my engagement Too confused about everything, confused about life, about my lessons for marriage, about___. I DON’T KNOW??????????????????? I was told yesterday about ___ I got such a shock!!

I would need to find my vagina before my husband did.

Chana Rabinowitz leant forward in her chair. “Did you say it was someone at school?” she asked. I shifted back into the brown striped couch to widen the space between the counsellor and my overwhelming shame. Her eyes were wide and focused, waiting for my response. I fixed my gaze on the white tiles of Chana’s living-room-turned-therapy-office in Jerusalem; the same tiles that covered the floor of every Israeli apartment. I had started seeing Chana after falling into a depression, following my marriage and a year and a half of infertility that made me question my place in this world and turn to the forbidden internet for answers.

I knew the next question was coming before she asked it. “Who? How did a man have access to you at school?” she asked, a puzzled look on her face. Having worked within the Adass community, Chana was familiar with the rigid gender separation. I stayed silent. There was a quick, throbbing pulse in my throat, preventing me from speaking. Our previous session flashed through my mind. Somehow, my struggles with marriage and intimacy had led Chana to ask if I had been sexually abused. A slight nod and I had ended up here, in this mess. “It wasn’t a man,” I heard myself say, and then suddenly I was in a taxi home with my head in my hands, mourning what I had shared.

The week after my disclosure passed in the same manner as every other week. I spoke to my family back home but didn’t tell my sister Nicole how I had muttered four words that had the potential to change everything. I suspected Mrs Leifer had abused Nicole after I witnessed her climb into my sister’s bed one camp night in 2006. In the dark room we shared with our principal, I’d heard the sounds of my worst fears. The next morning, standing outside our cabin, no words were exchanged, but our eyes met in a way that conveyed a mutual understanding.

I agreed to another session with Chana on Thursday. There was a sombre feel in the room and a contemplative look on her face as she ushered me in. Chana began immediately. “I’ve thought of every female teacher at the school. I can’t begin to imagine who it is. I need to speak to Malka Leifer,” Chana said.

“No, don’t do that,” I cried out. “Please don’t talk to anyone.”

“If the teacher still works at the school, I need to tell Mrs Leifer,” she said firmly.

“It wasn’t a teacher,” I managed to whisper.

Nicole called me later that night. “You told Chana Rabinowitz,” she said, surprise and worry in her voice.

“I didn’t feel like she believed me,” I told her.

“I know – she wanted to know if it was really true,” Nicole responded.

“What did you tell her?” I asked. My heart was pounding and my throat was dry. I had never spoken to Nicole about what happened with Mrs Leifer. There was still a chance that she had shut this down and told Chana it wasn’t true. The part of me that was hoping she’d shut this down was almost as strong as the part of me that just wanted to be believed. “I told her it was true,” she confirmed. “It feels like Chana went into panic mode. She said she needed to alert the school.”

“What’s going to happen now?” I asked my sister. “Will they believe us?”

“I don’t know,” Nicole said. “I’m so scared. What if Mrs Leifer finds out we said something?”

A few days later, Nicole called me again. She told me the school board knew of other allegations, and that she had been advised on what to do if approached by Leifer. That was when I knew this story was no longer only mine.

At that time, Nicole was teaching at Adass School in Melbourne. Leifer had pulled her out of the Grade Six classroom to ask her what she knew. Nicole believed Leifer had been told that the school was aware she was molesting students. Having been advised not to respond to Leifer’s questions, she dutifully told the principal she did not know anything. What we truly didn’t know was that immediate plans were being made to get Leifer out of Australia. By the next morning, she had fled to Israel.

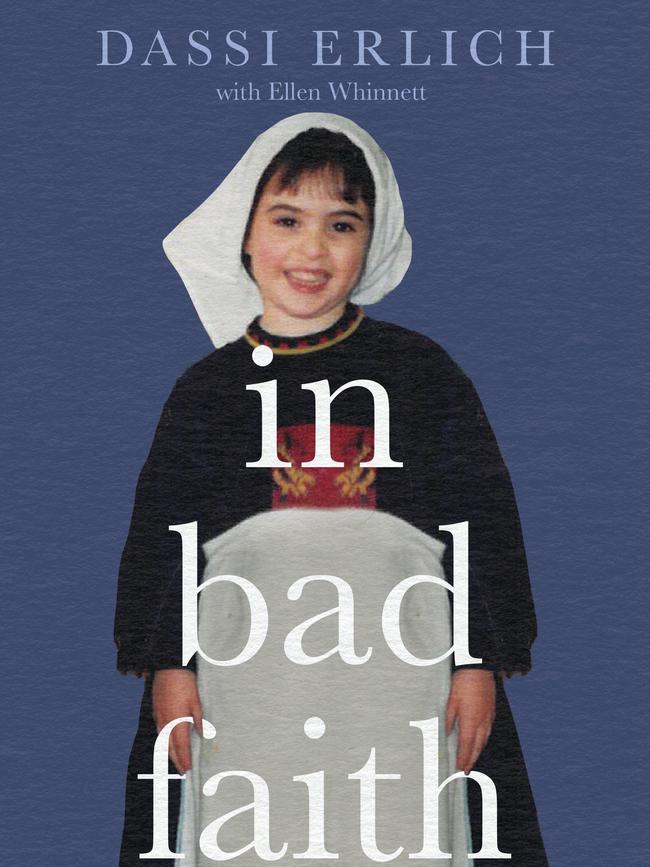

In 2015, Dassi Elrich sued Adass Israel School for negligence and received a $1.27 million payout after it emerged that the Board of the Adass Israel School had orchestrated Leifer’s departure from Australia. In March 2017, Dassi went public with her first interview – a profile by Cameron Stewart in The Weekend Australian Magazine that became the catalyst for a campaign to extradite Leifer. The Israeli government finally signed an extradition order in 2021. Leifer was committed to stand trial in Victoria’s County Court in 2023.

Just days before the trial, Detective Danielle Newton informed me that the defence wanted a copy of a manuscript I was working on. I was distraught. This was my story, in my own words. How could I surrender those words to be exploited, used as weapons against me? But all this had to be given to them. Nothing was sacred or beyond their reach, it seemed.

I spoke to Ailsa McVean, the solicitor responsible for our case. I was struggling to come to terms with the thought of them tearing me apart with my own words. Ailsa assured me they would redact anything not relevant to Leifer or my childhood, but as I went through the book I could not find a single chapter since Leifer had entered my life where she wasn’t somehow involved. It took several sleepless nights and a frenzy of diary writing to realise she had impacted every period of my life since she chose to abuse me. In my diary that night, in bold, underlined letters, I scrawled, “I will not let Leifer define my life any longer.”

“I’m doing this all for you,” I whispered to the image of my younger self in my mind, the one who had endured so much in silence, too terrified to speak up. I was not her anymore.

The third day on the stand was incredibly intense as I faced Ian Hill KC for cross-examination. They brought out my diary entries, and I wanted to chuckle at my younger self and at the same time cry for her innocence. Then they began reading from the chapter I had written in my own book where I detailed my confusion and distress around Leifer’s abuse. The entire courtroom was silent, absorbed in the words. Halfway through the morning, the judge excused the jury. Hill intended to ask about my father, but the judge had not yet ruled that he would allow this line of inquiry in front of the jury. The fate of that decision rested on the answers I gave next. I was asked a series of questions by the defence, followed by a few from the prosecution. Then I was given the draft of my book and asked about this paragraph:

I’m not sure when I confessed to the principal that I wanted to share something I was troubled about … Mrs Leifer set me up for a private phone call with a rabbi’s wife ... I was able to tell her that my father gave me hugs that were uncomfortable.

Both parties asked me which year the incident took place. I searched my memory desperately; I believed those calls had been made in Year Ten, but there was no clear memory to tie it to a specific time. “I cannot provide a definite answer,” I told them.

For the rest of the trial, Hill would use this uncertainty to accuse me of lying. “Why would Dassi go to her ‘abuser’ for help about another abuser? And why would Leifer give her the name of her mentor without being worried that she might be exposed?” he would question.

On my fourth day in the witness box my body felt depleted, as if there was nothing left to give. It seemed to me that Hill’s tactic that morning was to bore everyone to death. He asked the same questions repeatedly in various ways, about details I had already confirmed I did not know. He wanted to know which classes I had attended on the day of an incident, or how many and which teachers were at camp. I remembered the abuse, not the particulars of the days when it occurred, and his questions made it seem like my memory was unclear. In his closing arguments, he told the court that I had said “I don’t know” 160 times. Of course, he could spin it however he pleased; I was only allowed to answer the questions he asked.

I could feel my younger self being forced to endure the pain all over again. I couldn’t understand why the defence was allowed to try to break me, and why I was expected to remain composed in the face of such pain. What did a moment of vulnerability imply? Falsehood? The system felt deeply unjust to me, as if it punished victims for having the courage to speak up.

Monday marked the fifth and final day of my testimony on the stand. The judge allowed the defence to ask me about my father, and I told the jury how he had touched me inappropriately. Hill’s questioning insinuated that I could not have been entirely unaware of sexual abuse, suggesting that my prior abuse somehow made me knowledgeable about such matters. I had to fight every urge to scream at him.

Twelve years of remembering in such excruciating detail is over now, I told myself that night. I give myself permission to forget. I had done my part. What they did with my truth was now up to them.

Malka Leifer was convicted of 18 offences against sisters Elly Sapper and Dassi Erlich, committed between 2003 and 2007. She was acquitted of nine charges, including some relating to the alleged abuse of Nicole Meyer. Leifer was sentenced to 15 years in prison. b

In Bad Faith by Dassi Erlich with Ellen Whinnett (Hachette) is out on January 31

More Coverage