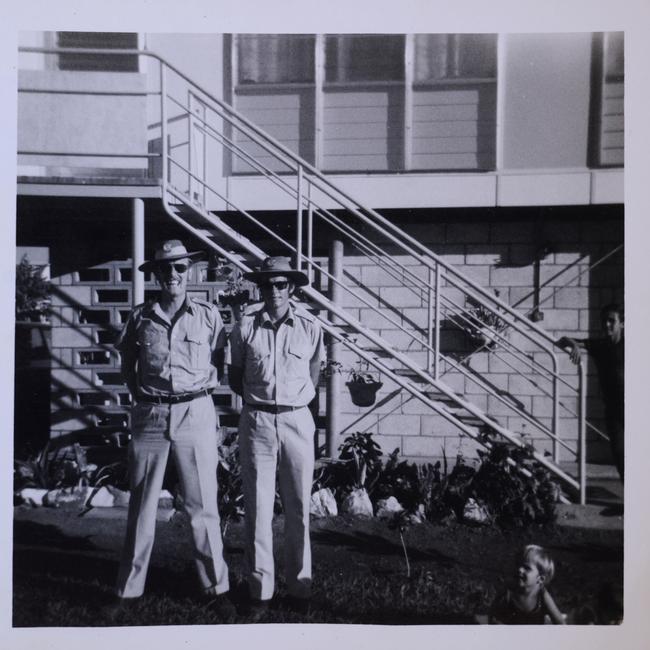

Fifty years later Bill Jauncey doesn’t know how he held on with two fellow guards and more than 90 prisoners in their custody, as Darwin’s Fannie Bay Gaol was torn to pieces by Cyclone Tracy.

It has taken Bill Jauncey half a century to talk about what happened in Darwin when Tracy came calling at Christmas 1974. He was a prison officer back then, rostered on the graveyard shift at Fannie Bay Goal. He can still picture the surreal drive to work while the town battened down. The coconut palms were bent double, as if bowing to the gathering storm. Jauncey had never seen the like of it. He parked his car and rushed inside, lashed by sheets of icy rain. It was 9.30pm, the start of the longest night of his life.

Over the coming hours he would wonder whether he would live to see the light of day. “I can’t tell you how many times I thought, ‘This is it, I’m not getting out of here,’” he remembers. It’s a common refrain among those who went through Tracy, that mother of all tropical cyclones. Survivors say they never felt so alone, utterly helpless before the implacable fury of nature. The wind speed was clocked at 217kmh before the recorder at the airport blew apart, along with 94 per cent of Darwin’s housing stock, including Jauncey’s home. The human toll was horrific: up to 71 dead, 650 injured and some 40,000 people left without a roof over their heads. For all intents and purposes the lush Top End capital had been wiped off the map.

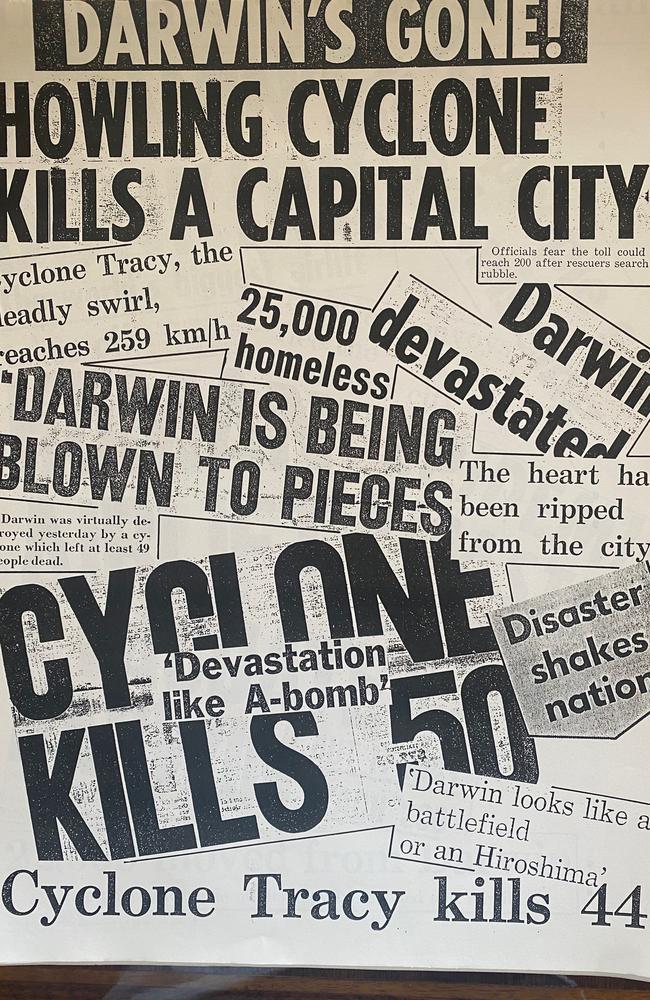

You may know something of the epic scale of the disaster. No fewer than 20 books have detailed Darwin’s destruction and subsequent military-led evacuation, one of the biggest peacetime operations mounted on Australian soil by the armed forces. There’s been a TV miniseries, official reports by the truckload and bursts of publicity as the anniversaries rolled by: 10 years, 25 and now the 50th, possibly the last opportunity for the people who were there to tell it like it really was.

Yet the story that never came out was the one that took place behind the corrugated iron walls of the prison. Out of sight meant out of mind when there was so much to take in and do in the grim aftermath of Tracy. Even now, Jauncey doesn’t know how he held on with two fellow guards and the 90-odd prisoners in their custody. The jail was torn to pieces around them.

For a heart-stopping time, the maximum security inmates were at risk of drowning in their locked-down cells. The walls peeled off the dormitories where others cowered. The men – and they were all men, after the lone and heavily pregnant female prisoner (a woman in her early twenties) was sent home to her parents – knew they were on their own. No one was coming; no one could.

The three prison officers retreated to the gatehouse and upended a heavy oak table. It offered some protection against the flying debris, but not much. Soaked to the skin in his light khaki uniform, teeth chattering from the unexpected cold, 25-year-old Jauncey huddled between his older colleagues and thought about his little boy, Darren. “The noise was incredible … like you were standing a couple of feet away from a jet engine going flat out,” he reflects. “It hurt your ears, it was that intense. There were bits and pieces of things, metal sheeting, you name it, hitting the front of the table and you could feel the force. You didn’t dare stick your head up. You couldn’t say anything, you couldn’t do anything, you just had to sit there and cop it. And then, of course, the eye comes through. That’s when things got really bad for us.”

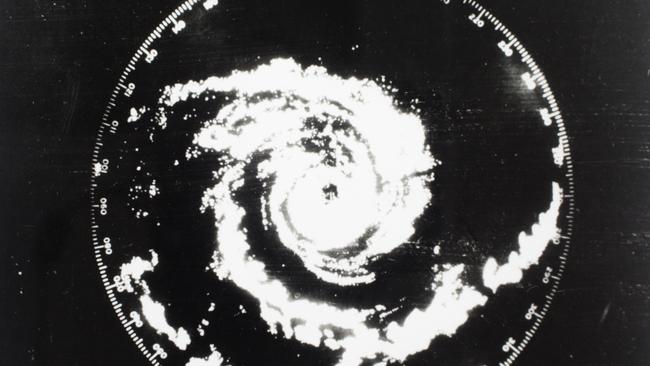

To begin with, Tracy had seemed like a non-event, hovering in the steamy Arafura Sea north of Darwin in the countdown to Christmas. Ho hum. Three weeks earlier people had gone into a tizz when Cyclone Selma was predicted to make a direct hit; instead, it performed a U-turn without sending so much as a drop of rain their way.

The sense of complacency was reinforced when ABC local radio reported on December 22 that Tracy posed no immediate threat – it was tracking southwest, away from the city. That all changed on Christmas Eve when it rounded the Tiwi Islands. The Bureau of Meteorology issued its first explicit alert for Darwin at 12.30pm, warning the approaching system was packing winds of 120-150kmh.

Still, no one panicked. The festivities continued. By now, it had swung onto a southeasterly course and was making a beeline for the NT capital. And the collision of an upper-level trough with the seasonal monsoonal flow would intensify the swirling maelstrom in a wholly unexpected way. Rather than swell in size, the cyclone underwent explosive decompression. The eye contracted to a tornado-esque radius of just 6km, turbocharging it. Reconstructions would show that Darwin was smashed by 300kmh winds.

When Jauncey reported for his shift at the prison, the power and phones were already out in most suburbs. Given he had drawn the short straw on the Christmas roster, his wife, Tricia, had flown to Broome with toddler Michael to catch up with her brother, Pat Dodson, the future titan of Indigenous affairs. Darren, three, was being minded by friends in town.

The century-old jail was pretty much full, as usual. Three guards for 85 to 95 prisoners that night – Jauncey’s best guess – was also par for the course. Like his experienced colleagues, Boris Baranovsky and Keith Bottomley, the young man carried a Colt 45 revolver on his hip, loaded with five bullets. (An empty chamber was set adjacent to the hammer for safety.)

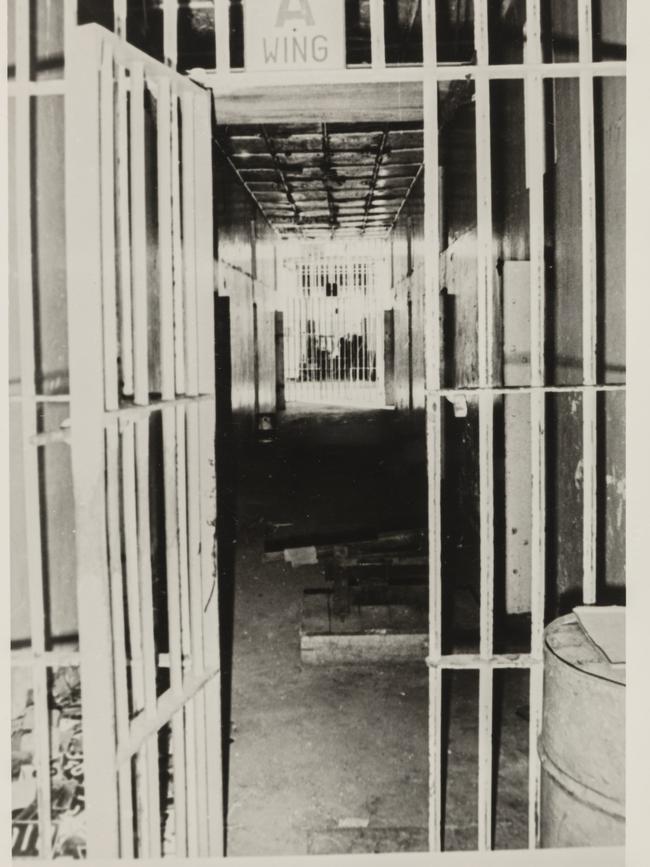

What it lacked in amenity, the prison made up for in its position atop a sandstone cliff overlooking Fannie Bay. It was divided into three sections: A and B wings where the maximum security prisoners were housed in concrete cells with clanging steel doors; the grilled dormitories in C, D and E blocks for lower-risk inmates; and a small women’s compound. The joke was you could break through the iron-sheeted perimeter walls with a can opener.

Jauncey’s station was in a passageway between A and B wings. But by 11pm it was obvious none of the guards would be making their hourly rounds. “Sheet metal was flying everywhere and you couldn’t see a thing,” he says. “It was becoming dangerous.”

Holed up in the gatehouse behind the overturned desk, they heard the nearby administration building collapse with a crash. They could taste the salty seafoam driven over the 15m cliff by the force of the wind. The normal tidal variation was 8m – so what would a storm surge add? At least the cyclone had struck at low-water; on that count, at least, they were lucky. But on crossing the coast at about midnight, Tracy did something unexpected. Typically, cyclones soon move inland and weaken. But Tracy remained virtually stationary over Darwin, pounding the city for hour after hour.

Suddenly, the wind dropped. The eye at the centre of the storm had arrived, and with it an eerie quiet. The prison officers knew they had a window of about 30 minutes to check on the inmates, whose anguished cries for help could now be heard. They decided to stay together, just in case someone had broken out. First stop was maximum security. There, Jauncey was appalled to find the 15 prisoners standing in water, halfway to the knees. Their locked cells were filling, unable to drain with the solid outer steel door to the wing secured. These hardened criminals were terrified they would drown. “We won’t let that happen,” he assured them.

But what to do? After talking it over with Baranovsky and Bottomley, the decision was made to open the outer door. A breakout would be made easier, but so be it. They went from cell to cell, quietly explaining that, come what may, the prison was the safest place to be. Making a run for it would be pointless. The lull wasn’t going to last much longer – and when the eye passed it would be worse than ever. Jauncey told them:

-

“We’re all in this together. We’re just going to have to ride it out.”

-

The plight of the lower-risk prisoners in the dormitories was even more acute: the sheeted walls had been ripped away, leaving the men exposed to the elements behind a framework of steel grilles. One of them had completely lost control. He was trying to smash his way out with a lump of metal debris. Jauncey managed to talk him down, repeating the no-bullshit message he had delivered in maximum security. “There’s nowhere to go, mate,” he told the wild-eyed fellow.

The three prison officers stayed out too long and were caught in the open when the cyclone returned. Jauncey was struck in the torso by an iron gate that was blown off its hinges, winding him. He carried on, but didn’t it ever hurt. A big problem, as he would later discover. They made it to their bolthole in the gatehouse thinking the situation couldn’t get any worse.

Naturally, it did. “I mean, everything had already been weakened. There was debris flying everywhere, everything was crashing around us,” he says. “We’d hear another noise and we didn’t know whether part of the building had gone … And those poor buggers locked up. We were in rough trouble ourselves but I was thinking what it must be like for them and how frightened they had to be because I was bloody terrified. We were getting hit by debris, all kinds of stuff, so I knew there was a chance the prisoners were being injured. There was nothing you could do about it. We had this sense of being completely helpless.”

Jauncey honestly couldn’t see how anyone would survive. He resigned himself to his fate. The only comfort was that Tricia and little Michael, 18 months, were out of danger in WA. He thought about Darren and prayed the boy was safe at his friends Brett and Christine Nudl’s place in nearby Jingili. “I kept thinking, ‘As long as he’s alive, I’m happy to go.’ That sort of kept me going. If I was going to cop it, I just wanted it to be quick … for something to hit me and just knock me straight out,” he recalls. “Boris [Baranovsky] and I talked about it the next day and I know he had similar views.”

They lost track of time. But eventually, the noise and mayhem subsided. The prison officers emerged about 4.30am to abject devastation. The jail was one giant mess. The 2m searchlight mounted above the maximum security wings had been ripped free, landing in the passage where Jauncey’s original overnight post had been, along with its boulder-like foundations. Had he stayed put he would have been killed. Entire sections of the corrugated iron perimeter walls were gone or at best hanging by a few nails; so much for maintaining security. The dining hall, laundry and dispensary were a shambles, as were the wrecked dormitory blocks where most of the inmates were held. They were wet, cold and miserable, bruised and battered from head to toe. The fear they had endured through a long and trying night threatened to turn to anger.

Feeding them might help, Jauncey knew. So the kitchen detail was put to work preparing bacon and egg sandwiches to be sent around the wings. Buckets of tea and coffee were brewed. The morning shift was due to come on from 6am but not one of the rostered prison officers showed. To the dismay and frustration of Jauncey and his exhausted companions, they were still on their own.

The inmates were increasingly ill-tempered in their sopping clothes when supervising prison officer John Howlett turned up about 10am on Christmas morning. Jauncey could have kissed him. He was sick with worry about his boy Darren, while Baranovsky and Bottomley were equally desperate to reach their own families. They could see the damage to the city from the surviving watchtowers: street after street of destroyed homes, the trees picked clean of foliage. Formerly green and verdant Darwin looked like a moonscape.

Clearly, the prisoners couldn’t stay where they were. The jail was not only insecure, it was unsafe. There would be a riot if they weren’t transferred. The prison officers were standing outside the caved-in front gates, considering their options, when a blue and gold municipal bus chugged around the corner. They drew their handguns to stop it.

The driver, Lionel Butler, wisely pulled over. “We didn’t actually put a gun on him, it was more a show of intent,” Jauncey says. In the event, Butler was a good sport whom he knew from football. Baranovsky, a former Navy man, suggested they load up most of the prisoners and drive them to nearby Larrakeyah Barracks, where the soldiers would take over. Howlett agreed to stay on at the prison with a team of trustees to start the clean-up.

Unfortunately for them, the Australian Army had other ideas. The packed bus was turned away by armed sentries at the entrance to the barracks: they had their own problems to deal with. “We were told in no uncertain terms to move on,” Jauncey says.

They decided to try the new downtown police centre in Mitchell Street. His voice starts to shake as he describes the scene they encountered. A party of policemen led by a sergeant was unloading something bulky from a vehicle parked outside the station. Jauncey, who was first off the bus, looked closely and realised to his horror they were carrying a corpse. The body of a boy of about 10 or 11 lay in the back of the vehicle alongside that of a man he recognised. “We had been incredibly lucky that no one was seriously hurt or killed at the jail, but now it struck me how hard the community had been hit,” he says. “Knowing that man was a shock.”

It didn’t end there. The police sergeant turned out to be a sympathetic type, and agreed to take the prisoners for the night. They could use the holding cells. There was a problem, though: this was one of the few airconditioned spaces left in Darwin and it had already been pressed into service as a makeshift morgue. The bodies would have to be moved to the basement of the courthouse across the street. Could they help?

“It was done very respectfully,” Jauncey says. Each corpse, wrapped in a blanket, was gently placed on a stretcher and conveyed to the courthouse by the prison officers and inmates known to be reliable. Between a dozen and 17 bodies were shifted, allowing the Fannie Bay prisoners to quietly file into the vacated cells. The arrangement was strictly temporary. But it would do for now.

The obliging Butler then drove the trio back to the wrecked jail. A sleepless Jauncey was out on his feet. Baranovsky and Bottomley said they were going to find their families, and he should clock off as well because they had done all they could. Jauncey went to retrieve his car. It turned out he had parked under a building which was now just another pile of rubble. OK, he wouldn’t be driving anywhere.

Then he saw them, Brett and Christine Nudl. They had arrived at the prison with their four kids – and Darren. The tot was pale and withdrawn, but he was in one piece and that was all that mattered to his overwrought dad. The emotion came spilling out as they hugged. “I can’t tell you what relief I felt,” Jauncey recalls. It was the best Christmas present he would ever receive.

The days that followed were a blur. He eventually got home to find there was nothing to find: the family’s airy, high-set home in Wagaman was gone, reduced to a skeleton of pylons and broken joists, topped by a sad handful of floorboards. The walls, roof and nearly every possession they owned had vanished into the thick tropical air. “It was pointless trying to look for anything … most of the bits and pieces I could see had blown across from other houses,” he remembers.

He couldn’t thank his friends Brett and Christine enough. Brett, a fireman, had been on duty on Christmas Eve and was unable to get home before the cyclone hit. Plucky Christine had been magnificent. They had a bricked-in storeroom under the house where she retreated with the kids, covering them in hessian bags for added protection as the structure came apart. This had almost certainly saved his son’s life.

Jauncey couldn’t get through to Tricia. There would be no private lines out of Darwin for weeks. When he eventually got in touch he told his wife to stay in Broome: there was nothing – absolutely nothing, he stressed – to come home to. He would join her as soon as he could get away with Darren.

The question of what to do with the prisoners continued to vex. They would have to be evacuated alongside the 40,000 homeless residents of the devastated city. Martial law had been declared in Darwin and those who couldn’t leave under their own steam were being airlifted out. It took another 72 hours to settle on a solution: the prisoners would be taken by bus to the jail in Alice Springs.

Thanks to his new friend, the police sergeant, Jauncey and Darren had been put up at the Travelodge, a vast improvement on where most people were bedding down in schoolrooms or under canvas. But he was discomfited by some of the hotel’s gung-ho clientele. A clique of seconded federal police were on the drink after-hours, strutting around with rifles and cartridge-studded bandoleers “like something from a western movie”. There was talk of clashes at roadblocks between the police and Navy personnel involved in the relief effort. After all he had been through, the post-Tracy atmosphere in Darwin made him feel “unsafe”. Jauncey says he was glad to leave.

Darren clung to his side during the hot two-day bus ride to Alice Springs, brandishing a plastic toy gun – the one gift he had managed to salvage from home. The boy’s presence probably helped keep the prisoners in check. If not, they had been warned by chief prison officer John Gollan that anyone who stepped out of line could and would be shot. Nearly a week on from the cyclone, Jauncey was yet to hear from the prison management; there seemed to be no interest in how he was doing. He was deeply unimpressed. Baranovsky was supposed to be on the road with them, but had fallen ill.

At least he had a home to go to in the Alice. His sister Kay and her policeman husband, Mick Palmer, a future AFP commissioner, had insisted that he and Darren stay with them. Jauncey had never felt so tired when he walked through their door on December 30. He collapsed on New Year’s Day – not from exhaustion but a serious injury. The blow to the torso he had suffered at the height of the cyclone turned out to be a ticking timebomb, causing internal bleeding aggravated by an undiagnosed stomach ulcer. With everything that was going on, he had ignored the worsening symptoms. It seemed like an omen. Jauncey spent five days in hospital – plenty of time for him to think about things and realise he didn’t want to return to Darwin to live. Time to move on.

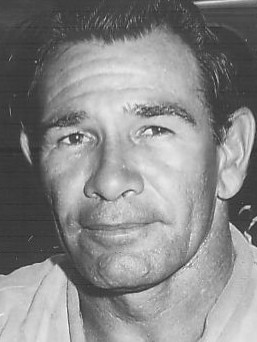

So why now? Why after all this time is he telling his story? Yes, the impending 50th anniversary makes it opportune. But that’s not the whole reason. You see, it has taken him years and years to come to terms with that fraught Christmas and there are still some memories he prefers to keep to himself. Too raw to share, even today. And he had to be convinced that people would be interested in what he had to say when the powers that be in the NT prisons service conspicuously hadn’t wanted to know.

“I didn’t think it would be worth it. I was angry about the way we were treated,” Jauncey, now 75, says from his home in Perth, referring to the silent treatment that he and his colleagues received from the brass. “I mean, we did something special together and not one of us got a pat on the back or a single word of acknowledgment. As far as I was concerned, that stank.”

The man who persuaded him to speak out was former Northern Territory chief minister and Tracy survivor Marshall Perron. (Perron and his wife Cherry sheltered in a wardrobe while their home was destroyed. He saved their lives by using a wire coathanger to hold the door closed in the whirlwind of broken glass.) It happened, as these things often do, by chance. Perron, 82, had mentioned to his friend, retired police chief Mick Palmer, that he was working on a speech to mark the half-century milestone. Palmer suggested he talk to his brother-in-law, because, boy oh boy, did he have a tale to tell.

As it turned out, Perron knew Jauncey, albeit in a different capacity: following the cyclone, Jauncey and his family moved to Canberra, where he started over as a porter at the airport with Ansett Australia, going on to a glittering career in aviation that brought him into contact with Perron. Among his claims to fame, Jauncey mentored a young Irishman named Alan Joyce; their paths would continue to cross as they climbed the ranks at Jetstar and Qantas, where Joyce eventually became boss. Jauncey retired in 2006 as head of ground operations for Jetstar Airways.

Perron had always wondered what transpired at the prison during the cyclone. “It was a mystery … there wasn’t anything in the archives and I couldn’t find anyone who knew about it,” he says. He told Jauncey he owed it to history – and those who were no longer around – to set the record straight. “I know it’s hard for you, Bill,” he said. “But we really should document this while we can. Would you be prepared to put something down on paper?”

Jauncey relented. However, he first needed to track down Baranovsky and Bottomley. They’d lost touch over the years but everything they did during and after the cyclone they did together, and he wanted them involved. “Boris and Keith were inspirational … the decisions we made that night and in the next few days were collective,” Jauncey says. It morphed into quite the undertaking because he didn’t stop with them as he uncovered new facets of the prison drama and its aftermath. Like him, those who survived Tracy were still grappling with the experience long after Darwin was rebuilt.

Baranovsky, aged 46 when the cyclone hit, died in 1994. His son Michael says his happy-go-lucky dad wasn’t the same man post-Tracy. “He basically went grey overnight … he never really got over it. He would have flashbacks all the time and … became a lot quieter, more withdrawn,” Michael says.

Bottomley left the prison service within weeks, embittered by the lack of support. Now in his late eighties and living in Canberra, he told Jauncey that he had never again been able to enjoy Christmas. “He still felt sad about seeing a boat out to sea that night sending up flare after flare, and obviously no one was able to respond,” Jauncey says.

Most of the others are long gone. John Gollan, the “lion of a man” who cleared the way for Darren to join him on the bus to Alice Springs, died some time ago, a “real old well-known Territorian”. Vale Lionel Butler, their champion driver. Jauncey couldn’t establish what became of John Howlett, the prison officer who turned up on Christmas Day at the shattered prison, and says he would like to have been able to tell him how much his calm presence meant. Equally, he wished he could remember the name of the friendly police sergeant from Mitchell Street: “He was so professional, a real hero and champion to us.”

As for his own family, he and Tricia welcomed another two children in the course of a 24-year marriage. She died of breast cancer in 2007 following their separation, aged 55; they remained friends to the end. Darren, now 53, struggled for a time, especially at Christmas. But the stoic little boy came good after a few years. Today, he has a son and two grandkids, as well as a successful career as a mine supervisor for BHP. Michael, 51, is in charge of the company’s Indigenous procurement program.

Jauncey ultimately agreed to not only tell his story to Perron, but allowed him to tape their lengthy conversations – which were adapted into a riveting essay they hope to place on the historical record with Library & Archives NT. He’s glad he did. Darwin’s ordeal needs to be remembered, its lessons handed down to future generations, Jauncey says.

Because if there is one thing he knows in his bones it is this: somewhere, someday, another Tracy will come spinning out of the blue of a tropical sea to visit death and destruction on an unprepared Australian community. Would your home survive the 300kmh onslaught? Would you? Don’t pretend we weren’t warned.

More Coverage

Jamie Walker is a senior staff writer, based in Brisbane, who covers national affairs, politics, technology and special interest issues. He is a former Europe correspondent (1999-2001) and Middle East correspondent (2015-16) for The Australian, and earlier in his career wrote for The South China Morning Post, Hong Kong. He has held a range of other senior positions on the paper including Victoria Editor and ran domestic bureaux in Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide; he is also a former assistant editor of The Courier-Mail. He has won numerous journalism awards in Australia and overseas, and is the author of a biography of the late former Queensland premier, Wayne Goss. In addition to contributing regularly for the news and Inquirer sections, he is a staff writer for The Weekend Australian Magazine.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout