Henry Kissinger at 99: ‘America is more divided now than during the Vietnam War’

Former secretary of state Henry Kissinger nominates the moment of America’s downward spiral, the world’s best leaders and the five qualities that define them.

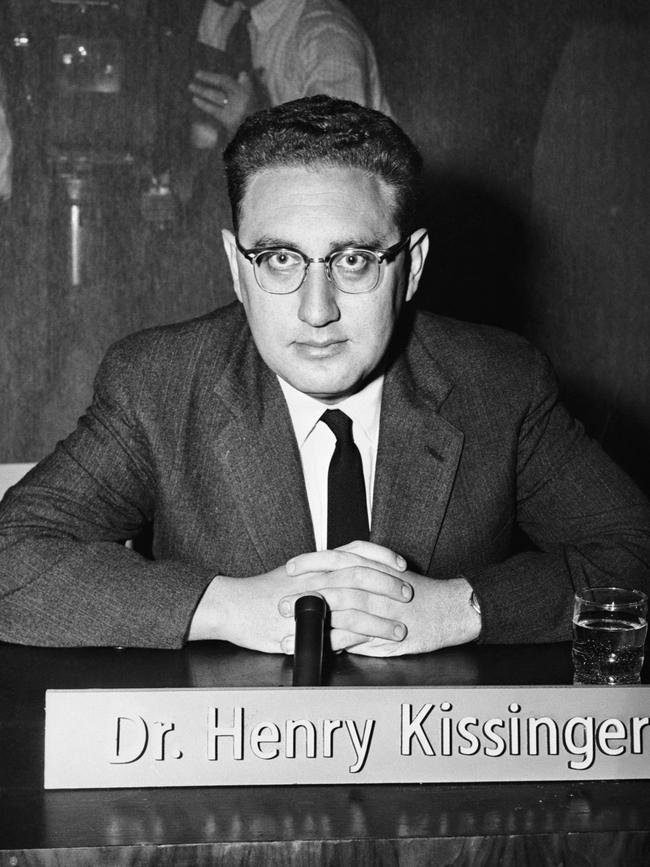

Henry Kissinger turned 99 on May 27. Born in Germany at the height of the Weimar hyperinflation, he was not yet 10 years old when Hitler came to power and was just 15 when he and his family landed as refugees in New York. It is somehow almost as astonishing that this former US secretary of state and giant of geopolitics left office 45 years ago.

As he heads towards his century, Kissinger has lost none of the intellectual firepower that set him apart from other foreign policy professors and practitioners of his and subsequent generations. In the time I have spent writing the second volume of his biography, Kissinger has published not one but two books – the first, co-authored with former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and computer scientist Daniel Huttenlocher, on artificial intelligence; the second a collection of six biographical case studies in leadership.

We meet at his rural retreat, deep in the woods of Connecticut, where he and his wife, Nancy, have spent most of their time since the onset of the pandemic – the first time in 48 years of marriage that the peripatetic Kissinger has come to an enforced halt. Cut off from the temptations of Manhattan restaurants and Beijing banquets, he has shed kilos. Though he walks with a stick, depends on a hearing aid and speaks more slowly than of old in that unmistakable bullfrog baritone, his mind is as keen as ever. Nor has Kissinger lost his knack for infuriating the liberal professors and “woke” students who dominate Harvard, the university where he built his reputation as a scholar and public intellectual in the 1950s and 1960s.

Every secretary of state and national security adviser (the first post he held in government) has had to make choices between bad and worse options. Antony Blinken and Jake Sullivan, who currently hold those positions, last year abandoned the people of Afghanistan to the Taliban and this year are pouring tens of billions of dollars’ worth of weapons into the war zone that is Ukraine. Somehow those actions do not arouse the invective that has been directed at Kissinger over the years for his role in such events as the Vietnam War (a significant amount of criticism has also come from the Right, though for very different reasons).

Nothing could better illustrate his ability to enrage both Left and Right than the controversy sparked by his brief speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos in May. “Henry Kissinger: Ukraine must give Russia territory” was The Telegraph’s headline in the UK, arousing almost equal numbers of enraged tweets from progressives who have added Ukraine’s blue and yellow colours to the latest version of the pride flag and neo-conservatives who are baying for a Ukrainian victory and regime change in Moscow. In a scathing response, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky accused Kissinger of favouring 1938-style appeasement of fascist Russia.

The oddest thing about the furore was that Kissinger said nothing of the sort. In arguing that some kind of peace must eventually be negotiated, he simply stated that “the dividing line [between Ukraine and Russia] should be a return to the status quo ante” – meaning the situation before February 24, when parts of Donetsk and Luhansk were under the control of pro-Moscow separatists and Crimea was part of Russia, as has been the case since 2014. That is what Zelensky himself has said on more than one occasion, though some Ukrainian spokesmen have recently argued for a return to the pre-2014 borders.

Such misinterpretations are nothing new to Kissinger. Years ago, vice-president Joe Biden was trying to persuade Barack Obama to pull out of Afghanistan when he drew an unfortunate analogy with disgraced former US president Richard Nixon. “We have to be on our way out,” Biden told veteran diplomat Richard Holbrooke, “to do what we did in Vietnam.” Holbrooke, Obama’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, replied that he “thought we had a certain obligation to the people who had trusted us”. Biden’s response was revealing: “F..k that,” he reportedly told Holbrooke. “We don’t have to worry about that. We did it in Vietnam. Nixon and Kissinger got away with it.”

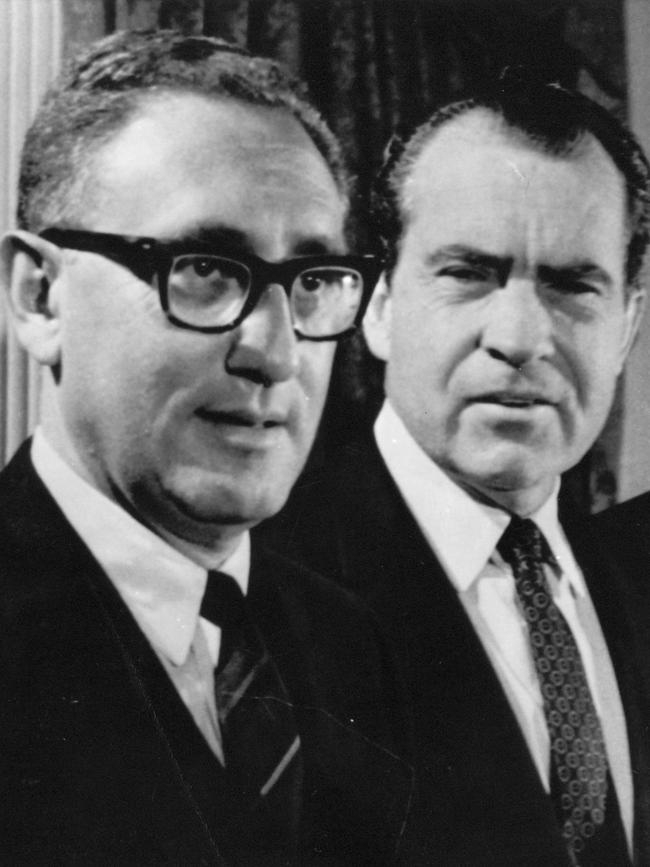

Yet the reality was, again, quite different. Nixon and Kissinger wholly rejected the idea of abandoning South Vietnam to its fate, as antiwar protesters urged them to in 1969. Rather than cut and run, they sought to achieve “peace with honour”. Their strategy of “Vietnamisation” was in fact a version of what the US is doing in Ukraine today: providing arms so the country can fight to uphold its independence, rather than relying on US boots on the ground.

Harvard and Yale types will splutter even more when they see Nixon as one of the exemplars in Kissinger’s new book Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy, rubbing shoulders with Konrad Adenauer, Charles de Gaulle, former Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and Margaret Thatcher.

I ask Kissinger how Nixon – the only president forced to resign – deserves a chapter to himself in a book on leadership. Isn’t he a case study in how not to lead? Kissinger starts with the succinct verdict on Watergate provided by Bryce Harlow, the experienced Washington operator who had been Nixon’s liaison man with Congress: “Some damn fool got into the Oval Office and did as he was told” – meaning someone in the White House had taken Nixon too literally.

“As a general proposition,” Kissinger says, “assistants owe their principals in politics not to be held to emotional statements [about] things you know they wouldn’t do on further reflection.” There were many times when, in the heat of the moment, or to impress present company, Nixon would give intemperate verbal orders. Kissinger learnt quickly not to act every time Nixon ordered him to “bomb the hell” out of someone.

“If you look at Watergate,” he argues, “it was really a succession of transgressions” – starting with the break-ins at the rival Democratic Party’s National Committee headquarters, which were ordered by the campaign to re-elect Nixon in 1972. Those transgressions then “came together in one investigation. I thought then and think now that they deserved censure; they did not require removal from office”.

From Kissinger’s vantage point, Watergate was a disaster because it wrecked the ingenious foreign policy strategy that he and Nixon had devised to strengthen the position of the United States, which had effectively been losing the Cold War when they came into office in January 1969. “We had a grand design,” he recalls. “[Nixon] wanted to end the Vietnam War on honourable terms … He wanted to give the Atlantic alliance a new strategic direction. And above all he wanted to avoid a [nuclear] conflict [with the Soviet Union] through arms control policy.

The Nixon that emerges from Leadership is a tragic figure – a master strategist whose unscrupulous cover-up of his re-election campaign team’s crime destroyed not only his presidency but also doomed South Vietnam to destruction. Nor was that all. It was defeat in Vietnam, Kissinger suggests, that set the US on a downward spiral of political polarisation. “The conflict,” he writes, “introduced a style of public debate increasingly conducted less over substance than over political motives and identities. Anger has replaced dialogue as a way to carry out disputes, and disagreement has become a clash of cultures.”

I ask if the US is more divided today than at the time of Vietnam. “Yes, infinitely more,” he replies. Startled, I ask him to elaborate. In the early 1970s, he says, there was still a possibility of bipartisanship. “The national interest was a meaningful term, it was not in itself a subject of debate. That has ended. Every administration now faces the unremitting hostility of the opposition and in a way that is built on different premises… The unstated but very real debate in America right now is about whether the basic values of America have been valid,” by which he means the sacrosanct status of the Constitution and the primacy of individual liberty and equality before the law.

A Republican since the 1950s, Kissinger avoids stating explicitly that there are elements on the Right that now seem to question those values. But he is clearly no more enthused by such populist types than he was in the days of Barry Goldwater, the 1960s presidential hopeful who was an arch defender of individualism. On the progressive Left, he says, people now argue that “unless these basic values are overturned, and the principles of [their] execution altered, we have no moral right even to carry out our own domestic policy, much less our foreign policy”. This “is not a common view yet, but it is sufficiently virulent to drive everything else in its direction and to prevent unifying policies… [It is a view held] by a large group of the intellectual community, probably dominating all universities and many media.”

I ask: “Can any leader fix this?”

“What happens if you have unbridgeable divisions is one of two things. Either the society collapses and is no longer capable of carrying out its missions under either leadership, or it transcends them…” Does it need an external shock or an external enemy? “That’s one way of doing it. Or you could have an unmanageable domestic crisis.”

I take him back to the oldest of the leaders profiled in his book, Konrad Adenauer, who in 1949 became the first chancellor of West Germany. At their last meeting Adenauer asked: “Are any leaders still able to conduct a genuine long-range policy? Is true leadership still possible today?” That is surely the question Kissinger himself is asking, nearly six decades later.

Leadership has become more difficult, he says, “because of the combination of social networks, new styles of journalism, the internet and television, all of which focus attention on the short term”. This brings us to his very distinctive view of leadership. What his sextet of leaders had in common were five qualities: they were tellers of hard truths, they had vision and they were bold. But they were also capable of spending time on their own, in solitude. And they did not fear being divisive.

“There must be in the life of the leader some moment of reflection,” he says, pointing to Adenauer’s time of inner exile in Nazi Germany; de Gaulle’s time as a German prisoner in World War I; Nixon’s wilderness years in the mid-1960s; Sadat’s jail time when Egypt was still under British control. Some of the most striking passages of the book are about these periods of isolation.

We turn to Margaret Thatcher, for whom Kissinger evidently developed affection as well as respect. At an early stage of the Falklands War, having just been briefed by Britain’s foreign secretary, Francis Pym, Kissinger asked her which form of diplomatic solution she favoured. “I will have no compromise!” she thundered. “How can you, my old friend? How can you say these things?”

“She was so irate,” Kissinger recalls. “I did not have the heart to explain that the idea was not mine but her chief diplomat’s.”

I suggest that the current prime minister, Boris Johnson, is almost the opposite of a leader as Kissinger defines it. Again, his answer surprises me: “In terms of British history, he’s had an astounding career – to alter the direction of Britain on Europe, which will certainly be listed as one of the important transitions in history. But it often happens that people who complete one great task can’t apply their qualities to the execution of it, which is how to institutionalise it.”

Carefully switching to discuss today’s leaders in general, he adds: “I would not be telling the truth if I said that the level [of leadership] is appropriate to the challenge.” I counter that we are surely being given a masterclass in leadership by the president of Ukraine, the unlikely figure of the comedian turned war hero. “There’s no question that Zelensky has performed a historic mission,” Kissinger agrees. “He comes from a background that never appeared in Ukrainian leadership at any period in history” – a reference to Zelensky being, like Kissinger, Jewish. “He was an accidental president because of frustration with domestic politics. And then he was faced with the attempt by Russia to restore Ukraine to a totally dependent and subordinate position. And he has rallied his country and world opinion behind it in a historic manner. That’s his great achievement.”

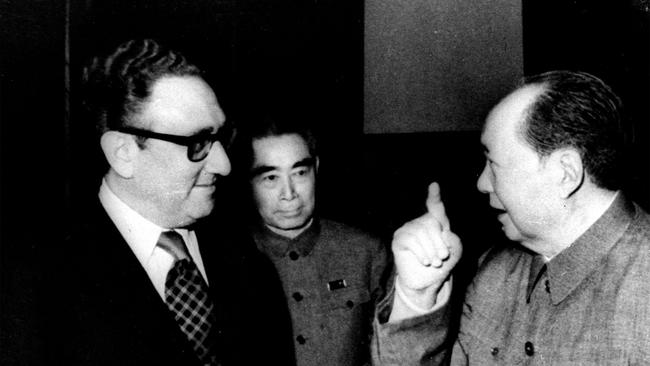

I ask for his thoughts on Zelensky’s adversary, Russian president Vladimir Putin, whom he has met on numerous occasions, dating back to a serendipitous encounter in the early 1990s when Putin was deputy mayor of St Petersburg. “I thought he was a thoughtful analyst,” Kissinger says, “based on a view of Russia as a sort of mystic entity that has held itself together across 11 time zones by a sort of spiritual effort. And in that vision Ukraine has played a special role. The Swedes, the French and the Germans came through that territory [when they invaded Russia] and they were in part defeated because it exhausted them. That’s his [Putin’s] view.”

Yet that view is at odds with those periods of Ukraine’s history that differentiated it from the Russian empire. Putin’s problem, Kissinger says, is that “he’s head of a declining country” and has “lost his sense of proportion in this crisis”. There is “no excuse” for what he has done this year.

Kissinger reminds me of the article he wrote in 2014, at the time of the Russian annexation of Crimea, in which he argued against the idea of Ukraine joining NATO, proposing instead a neutral status like that of Finland, and warning that to continue talking in terms of NATO membership risked war. Now, of course, it is Finland that is proposing to join NATO, along with Sweden. Is this ever-enlarging NATO now too big? “NATO was the right alliance to face an aggressive Russia when that was the principal threat to world peace,” he replies. “And NATO has grown into an institution reflecting European and American collaboration in an almost unique way. So it’s important to maintain it. But it’s important to recognise that the big issues are going to take place in the relations of the Middle East and Asia to Europe and America. And NATO with respect to that is an institution whose components don’t necessarily have compatible views. They came together on Ukraine because that was reminiscent of [older] threats and they did very well, and I support what they did.

“The question will now be how to end that war. At its end a place has to be found for Ukraine and a place has to be found for Russia – if we don’t want Russia to become an outpost of China.”

I remind him of a conversation we had in Beijing in late 2019, when I asked him if we were already in “Cold War II”, but with China now playing the part of the Soviet Union. He replied, memorably, “We are in the foothills of a cold war.” A year later he upgraded that to “the mountain passes of a cold war”. Where are we now? “Two countries with the capacity to dominate the world” – the US and China – “are facing each other as the ultimate contestants. They are governed by incompatible domestic systems. And this is occurring when technology means that a war would set back civilisation, if not destroy it.”

In other words, Cold War II is potentially even more dangerous than Cold War I? Kissinger’s answer is yes, because both superpowers now have comparable economic resources (which was never the case in Cold War I) and the technologies of destruction are even more terrifying. He has no doubt that China and America are now adversaries. “Waiting for China to become western” is no longer a plausible strategy. “I do not believe that world domination is a Chinese concept, but it could happen that they become so powerful. And that’s not in our interest.” Nevertheless, he says, the two superpowers “have a minimum common obligation to prevent [a catastrophic collision] from happening”.

It is time to leave. The nonagenarian may still be firing on all cylinders, but I have a plane to catch. A final inspiration prompts me to ask about the necessary corollary of leadership. “What about followership?” I ask. “Has that declined as well? Are people less willing to be led?”

“Yes,” he nods. “The paradox is that the need for leadership is as great as ever.”

There are those who will doubtless continue to demonise Henry Kissinger and disregard or disparage what he says. At 99, he can well afford to ignore the haters. Yet he has not lost his impulse to lead. “Leadership,” he writes, “is needed to help people reach from where they are to where they have never been and, sometimes, can scarcely imagine going. Without leadership, institutions drift, and nations court growing irrelevance and, ultimately, disaster.”

You are under no obligation to follow. But to drift to disaster without any leadership – or, worse, with fake leadership – seems like a worse idea.

Niall Ferguson is the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He is the author of Kissinger, 1923-1968: The Idealist.

Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy by Henry Kissinger (Allen Lane) is out on July 5.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout