Gunners of Long Tan: unsung heroes of Australia’s Vietnam war

At a dawn service with a difference, Catherine McGregor pays tribute to the gunners of Long Tan.

And so we gathered before dawn this morning. Well, actual crowds are banned right now, of course; but among a particular band of brothers, whose bonds of friendship were forged on Australia’s bloodiest day of the Vietnam War, this day could not be allowed to pass without some adherence to tradition. The original plan had been to come together at Warrnambool in Victoria but as any soldier will assure you, no plan survives contact with the enemy.

So this year, Covid-19 forced them to improvise. Improvisation comes naturally to the gunners of Long Tan – these men who served against a determined, brave enemy on foreign soil refused to be kept apart by an invisible viral enemy that has already infiltrated our national perimeter. And so we gathered around our screens this morning for a socially distant, virtual service, relying on technology that neither the original Anzacs nor the Long Tan gunners could have imagined.

My first dawn service in uniform was April 25, 1974. The entire crowd fitted comfortably around the Pool of Remembrance at the Australian War Memorial. My Duntroon classmates and I tunelessly joined a congregation of nuns in singing the traditional hymns. The crowds of 50,000 plus who, in normal years, gather at that place and time nowadays were inconceivable to us back then.

This year I was asked to deliver some remarks about the significance of this day as a guest of the gunners of Long Tan and despite the peculiarity of the format, it brought me even closer to some of those men whom I first met at the ceremonies to mark the 50th anniversary of the battle of Long Tan in Canberra in 2016. On that day I watched the gunners form three ranks and march to the service as a unit. They were in perfect step, with that languid yet orderly gait that is the hallmark of Australian soldiers. As they marched past me, I stood at attention. I wept without shame or restraint. Tears of pride. Tears of gratitude at being an ex officio member of this special group.

We have maintained contact since then. As we planned how to make this morning’s service work remotely I learnt more about them. Two of the men from 1 Field Regiment spoke at length about their memories of August 18, 1966, a day that came to define the Vietnam War among its veterans. John Burns and Doug Heazlewood represent everything I admire about the Vietnam veterans whose combat ethos and professionalism imbued every aspect of the Army I joined in 1974.

When Abraham Lincoln consecrated the cemetery at Gettysburg, he delivered one of the most memorable speeches in history. Yet even he conceded the limitation of mere words to pay tribute to the sacrifice of men who die in battle for ideals offering the “last full measure of devotion”. If Lincoln lacked the eloquence to pay tribute to his nation’s fallen, then I dare not even try. I can only attempt to give voice to what they told me as we planned this morning’s service.

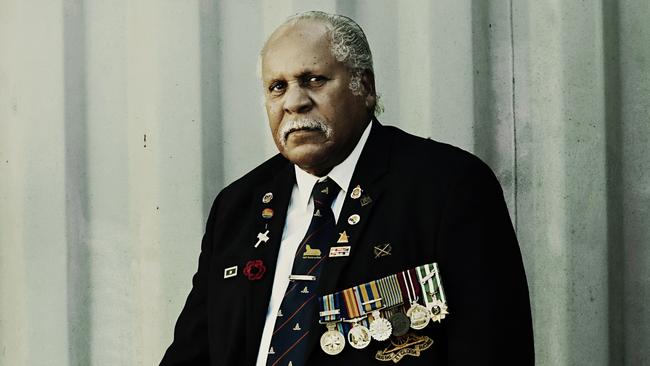

A true sense of being loved and of belonging eluded John Burns in much of his early life. He was born to an Aboriginal mother whom he never met. Adopted by an English woman who lived in humble circumstances in public housing in Holland Park in Brisbane, dependent on child endowment, she did her best to feed and clothe the young boy. John has never met his natural mother or father. Nor did he search for them. “To be honest I never got to the bottom of what happened. All I was told was that mum had not been able to keep me. It was all a bit vague really. Such a different time. I never knew whether that meant she just could not afford to or whether she didn’t want to keep me. But I just tucked it away and thought, ‘Well if you don’t want me, I don’t want you.’ I never pursued it. But these days you do feel it. And at times you wonder about who they were. But I just got on with it in the best way I could.”

He retreated into himself, while also resolving to escape poverty and earn a living at the earliest opportunity. His sense of difference was compounded every time he went out. “It was tough, you’d have to say. If my adoptive mum and I were walking out in public, people would stare at us. Sometimes they would say cruel things. Or maybe just thoughtless things. Sometimes it was abuse for sure. I shut it out. I had four really close Aboriginal mates as a kid. One, Ron Hurley, became an accomplished artist, while Allan Currie and Kevin Yow Yeh achieved rugby league stardom. But in Queensland at that time we knew we were viewed as different. Less than, in a lot of ways.”

Yet Burns, now 75, is remarkably unburdened by rancour or grievance. Quietly spoken, he is both a gentle man and a gentleman. He found deep love in his wife of over half a century, Valmai. His tone when speaking of her is reverential. “I owe her everything,” he told me.

He left school at 13 and found work in an abattoir. A mate suggested he join the Citizen Military Forces. He was not officially old enough to drink in a pub, join the army or hold a driver’s licence, but he’d done all these things by his 17th birthday. He learnt to drive in the CMF through his transport unit based at Ashgrove. He was drawn to military life and enlisted in the regular army, completing recruit training at Kapooka before being allocated to the Artillery Corps.

Despite his quiet humility, Burns possesses an inner steel that sustained him through two of the most brutal battles the Australian Army fought in Vietnam – Long Tan and Coral-Balmoral. Both involved Australian infantrymen and gunners standing their ground against overwhelming odds and staving off waves of assaults from a seasoned, motivated enemy. And it was here that he finally came to feel that he belonged to Australia.

August 18, 1966 was initially a normal day for Burns and his mates on the gun line behind the barbed wire and sandbag bunkers at Nui Dat. Though “normal” is an elastic term in a war zone. The day was clear. Cloudless. A visiting troupe of Australian pop stars including Little Pattie had staged a concert during the morning. Burns was one of the lucky ones who had been able to attend. He laughs at the recollection: “The movies and stuff have made it all look pretty glamorous. But it was hardly a rock concert like you see back home. It was all pretty improvised and the base was still at an early stage of being developed. I think some of them may have been performing on the back of a truck. I remember talking to a few blokes from the 6th Battalion who had to cut away from the show a bit early because they were going out on patrol. It all started out as pretty routine, though we had been mortared the night before and knew the VC [Viet Cong] had been probing the position.”

From the concert, Burns had gone on to his shift on the “at call” battery. Within his artillery regiment one battery of six guns was always manned and ready to fire at a moment’s notice if our troops outside the wire encountered enemy. While waiting they routinely trained and performed maintenance on the guns. As their shift ended, they covered the guns to protect them against monsoonal rain, which fell with clockwork regularity each day at that time of the year.

He and his mates were heading to their Diggers’ boozer to have their beer ration, engage in some of the usual banter and wind down for another day. When the Kiwi battery roared into action behind them, they were initially unfazed. “It was routine for the infantry blokes to register targets when they were in the rubber [plantation]. I thought that was what was happening. At that stage there was no hint we were in for a major fight.”

But neither Burns nor his mates got to open a single can of beer. The squawk box in their canteen screeched “Fire Mission Regiment!” That volume of fire without warning had never been required before. Burns and his crew raced back to their gun and sprang into action. The afternoon ultimately passed into history, but also into a personal montage of blurred images and vivid memories. “Our Gun Position Officer (GPO) John Griggs called out ‘Danger Close’ pretty soon after we went into action. So, we knew the blokes from 6RAR must have been really close to getting overrun. We were just pouring fire out and burning through our first line ammo.”

Each gun had 120 high explosive rounds within immediate reach. Extra ammunition was stored in a central ammunition dump. Burns and his battery played their part in the gruesome choreography of battle. All 18 guns of the regiment were firing rapidly. It is often overlooked that a battery from an American regiment, the 2/35 Artillery, chimed in with heavier calibre guns, bringing 24 guns to bear on a battlefield the size of couple of football fields. On the ground the men of Delta Company were clinging to their position. Wave after wave of enemy hurled themselves at the Australians. They held on. Barely. But it was the intense barrage emanating from their supporting gunners that wreaked most havoc among the enemy. Over the years I have spoken to numerous men of 6RAR. They expressed deep respect for the courage of the enemy. The ferocity of the assaults stunned them. They watched as many were vaporised by artillery rounds or grotesquely dismembered. Some have speculated the VC were hyped up on drugs, such was their frenzied, sustained determination to swarm at the Australians through withering fire.

Monsoonal rain began to thunder down, adding to the rain of death flooding into the rubber plantation from the tropical sky. Every gunner from 1 Field Regiment knew they would soon exhaust their first line supply of rounds and would be obliged to interrupt their barrage to replenish stocks. But any pause in fire support would permit the enemy to annihilate their mates in the plantation. Through the curtain of torrential rain, Burns saw soldiers from every unit inside the base running to the ammunition dump. Some had even come out of the Regimental Aid Post to break open spare ammunition crates so that men serving the guns did not need to pause. It was spontaneous. No one needed to issue an order. They knew what was at stake. They ran towards the fight to back their mates. Burns paused fleetingly to observe them breaking open fresh ammunition. He was flooded with adrenalin. But his heart leapt at an unfamiliar feeling. He belonged to something at last. A family. A band of brothers. One big army, without distinctions based on skin colour, religion or place of birth.

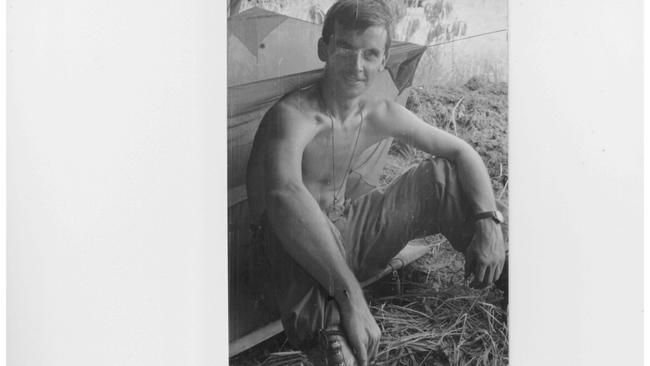

Doug Heazlewood, now aged 76, was a youngofficer posted to 1 Field Regiment of the Royal Australian Artillery upon graduation from Duntroon in December 1965. On that chaotic, desperate afternoon, he was a section commander (of three guns) in 103 Field Battery. He had already worked out that his job was to keep problems out of the way of his NCOs and gunners while they got on with the job they could already perform to a very high standard. After just 10 minutes of firing he could already see one problem he didn’t think he could solve: they were going to run out of ready ammunition in about 15 minutes and there was nobody to haul any more from the dump.

Heazlewood then saw the same human wave that inspired Burns running from HQ Battery to the gun position. For Doug, that sight meant his problem was solved – by quickly forming human chains from the dump to each gun, they ensured they could maintain their sustained deluge of death upon the enemy. The day could be saved.

I met Doug Heazlewood in Canberra in 2016 and have cometo know him over the years since. Our careers overlapped and we are of an age where we have more to look back upon than to relish with anticipation. We knew a lot of soldiers from the Vietnam era in common, and it is easy to lose an hour reminiscing. His dry humour has never deserted him despite battling cancer over the past couple of years. He has been pivotal in maintaining links among the men from Headquarter Battery, 103 and 105 Field Batteries for more than half a century since they wrote their own chapter in Australian military history and over that time has been a tireless advocate for his men.

In particular Heazlewood has lobbied for the gunners’ decisive contribution to the survival of Delta Company 6RAR to be properly recognised. The men have often felt that for too long their vital contribution on that day has been overlooked. Too many accounts of the battle focus exclusively on the incredible courage and cohesion of the rifle company in the plantation and ignore the vital role of fire support, the timely intervention of the cavalry unit in Armoured Personnel Carriers and the air resupply of ammunition by RAAF Iroquois helicopters.

Last year Heazlewood invited me to address the Warrnambool Anzac service. I had already committed to attend a commemoration at Acland in Queensland but was looking forward to joining him and some of those I had met at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Long Tan for this year’s service. As it turned out, the border between North and South Vietnam was more porous than that between the Australian states in these times of Covid-19, so we improvised. He asked me to record a message with a particular emphasis on the service of Vietnam veterans.

I returned to the War Memorial in my own uniform and medals. To honour my pledge to Doug and to John and every veteran of that war, I stood in front of the Vietnam Memorial a couple of weeks ago. Just me and a single camera operator in the gathering dusk to simulate the onset of dawn. I cannot remember what I said. I tried to speak from the heart.

But the deeds of those men and of those who have served this nation overseas speak for themselves. In our present time of trial, they remind us that endurance, resilience and unselfishness are the qualities that ensure victory. They embody everything I love about our Army. They deserve our gratitude and respect. Lest we forget.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout