Gun for hire: David Boies, the lawyer pursuing Prince Andrew

David Boies destroys opponents on the witness stand and has secured settlements of more than $1bn. Now he’s going after Prince Andrew.

David Boies is tall and rangy and in 50 years he has built a reputation as a masterful litigator who destroys opponents on the witness stand. When he rose to question a former commander of US forces in Vietnam during a libel trial, reporters in the gallery were said to have hummed the theme from Jaws. They weren’t humming for the general. His humiliating cross-examination of Bill Gates almost led to the dissolution of Microsoft; a few years later, a pioneering case he fought and won in California helped pave the way for marriage equality in the US. In the commercial world, he became known as a lawyer who could save your company: nine times he has secured settlements of more than $1 billion.

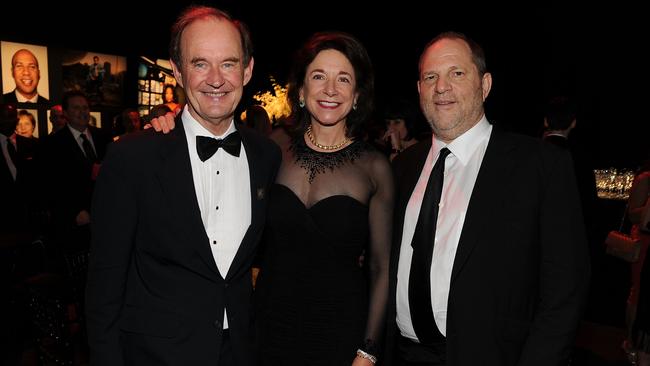

More recently he has been muddied by controversies related to his work for Harvey Weinstein, the disgraced movie mogul, and for Elizabeth Holmes, founder of the blood-testing start-up Theranos, who is now on trial for fraud. Boies was accused of threatening people and of adopting underhand tactics. He disputes this, though it only burnished his reputation for ruthlessness in a fight. This is the 80-year-old lawyer who is leading the case against Prince Andrew. “I really don’t view this as taking on the royal family,” he tells me.

We’re at the US Open, perched above an outer court at Flushing Meadows. It is three days before the first pre-trial hearing in the case of Virginia L Giuffre v Prince Andrew, Duke of York. Boies filed this lawsuit in New York in August, accusing the duke of sexually abusing Giuffre on three occasions, including once at his friend Jeffrey Epstein’s mansion in Manhattan, when she was 17 and not yet an adult under New York law. The duke sexually abused Giuffre “when she was a frightened, vulnerable child with no one there to protect her”, the suit said. “It is long past the time for him to be held to account.” The duke denies the allegations.

“I view this as taking on one particular person who engaged in conduct that I am sure the royal family privately disapproves of, as much as anybody else,” Boies says. “Now when it’s a member of your family it’s always hard, I know. I sympathise very much with the Queen, in the same sense that I sympathise with any mother whose child ends up in the kind of trouble Prince Andrew’s had.”

Andrew is meant to be her favourite, I say. He nods. “Makes it harder,” he replies, his eyes trained on the players beneath us. You might wonder what we’re doing at the tennis. Boies’ clients probably wonder this too, occasionally. This is a man who can bill $1950 an hour. But he’s also a huge fan. He’s nearly always here during the tournament, even if he has a major case coming up. There’s always a worry that one of his clients, watching the tennis on television, will spot him in the crowd and ask, “Why aren’t you working on my case?” he says.

The first time I speak to him about the Giuffre case, he’s aboard his yacht. Now, at the US Open, he’s wearing a baseball cap bearing the initials of the firm he founded, Boies Schiller Flexner. I tell him I’ll leave the big questions of life and death until we are sitting down somewhere and he nods. “Wait till we’ve had a drink,” he says.

As we watch the game, we talk in low voices. He was on the phone on the way here, he murmurs, supervising the filing of a report to the judge on efforts to serve the duke with the lawsuit and a summons. “The popular image of chasing Andrew down horse paths to throw the papers at him is a little bit of a misconception,” he says. But his firm did dispatch a corporate investigator who pitched up with the papers at the Royal Lodge in Windsor. The security team had been instructed “not to allow anyone onto the property” to serve court papers, the investigator said in an affidavit. Though eventually they gave him a number for Gary Bloxsome, who was said to be the duke’s solicitor, so he could call and leave a message. Bloxsome wrote to a senior judge in London complaining about this and advancing an argument as to why the duke might be shielded from any liability in the case, while at the same time maintaining he was not actually representing the duke. “It’s too clever by half,” Boies says. “This idea that everyone says, ‘I’m his lawyer, here’s some arguments, but I’m not his lawyer in this case, you understand.’”

I ask if he thinks Andrew’s lawyers will show up at the first hearing. “It’s almost never a good idea not to show up. That’s one thing that lawsuits and tennis have in common. It’s easier to win a game if you’re there returning the ball.” Someone did turn up to act for the duke. Andrew B. Brettler, a Hollywood lawyer who has previously represented disgraced actor Armie Hammer, attended the hearing and said he had “significant concerns” about the lawsuit. A few days later, London’s Judicial Office announced that “lawyers for Prince Andrew have indicated that they may seek to challenge the decision of the High Court to recognise the validity” of Boies’ summons. The duke, Boies says, has been acting like an ostrich and putting his head in the sand. “He really can’t hide from this.”

Boies grew up in a farming town in Illinois, theoldest of five kids. At school he struggled to read. “I think I displayed aspects that indicated that I wasn’t stupid,” he says. “I didn’t read at all until the third grade, but I could listen. I could reason. I actually did pretty well in school, just by listening to what people said.” Decades later, when one of his children was struggling to read, a clinician insisted on testing Boies too and found he was dyslexic.

The writer Malcolm Gladwell uses Boies’ legal career in his book David and Goliath to argue that in some cases dyslexia can prime a child for success, even in a profession that involves mountains of reading. Boies was forced to develop a phenomenal memory, to listen intently to what people were saying and to think on his feet. He told Gladwell that “learning by listening and asking questions means that I need to simplify issues to their basics and that is very powerful, because in trial cases [with] judges and jurors, neither of them have the ability to become an expert in a subject”.

Boies faced Bill Gates in the late ’90s, when the Justice Department hired him to lead their lawsuit against Microsoft, accusing the company of rigging its operating system to make it harder for competitors who wanted to provide web-browsing services. Gates seemed “a powerful enemy” and potentially “a very dangerous witness”, he says. “I met with him before we sued and he was a brilliant advocate for his position, articulate, organised. And when I took his deposition that’s what I thought I would be facing.” But, “He just tried to play word games, essentially, and you can’t get away with that,” he says. “He just gave me a lot of opportunities.” Tapes of the deposition were played, to devastating effect, at the trial. They were later made public. Gates complained Boies was “out to destroy Microsoft” and if so he almost managed it. The court ordered that Microsoft be broken up into separate companies, though the company was kept intact by an appeals court and the Bush administration.

Boies had the reputation, by now, of a living, breathing Atticus Finch. He represented Al Gore in Florida and before the Supreme Court in the bitter aftermath of the disputed 2000 election – 32 days working “night and day”, he says. Florida’s Supreme Court upheld the recount, then the US Supreme Court stopped it in what Boies regards as “one of the four or five worst decisions” it has made.

I ask about Weinstein. Before investigative stories appeared in October 2017, he says, “I don’t think anybody was aware of credible allegations that there had been forcible sexual abuse”. The New Yorker revealed that Boies, acting for Weinstein, had months earlier signed a contract with an Israeli company called Black Cube, directing its corporate intelligence operatives to uncover information that would halt the publication of negative stories about him. Boies says he signed the contract because there had been a dispute between Weinstein and Black Cube he had to help resolve. He then had to draw up a new one. “The contract I signed was simply to investigate charges that were being made by a woman that Weinstein emphatically denied,” Boies says. “Our first job was to try to find out what she was saying. There is a certain hypocrisy about hiring private detectives… The New York Times hires private detectives in their defamation lawsuits.” Boies was well placed to know this because it so happened he was also representing The New York Times. He was promptly fired. “They were very cross,” he says. He thinks they took the view “that only they should be able to hire private investigators… [But] if you are a lawyer representing a client, it’s malpractice not to find out what the facts are and to try to find out the best evidence that can support your client.”

As for Elizabeth Holmes and her pin-prick blood-testing start-up, he found her very convincing, although, “It was not so much her as the people around her. You had the chairman of the Stanford chemical engineering department… top doctors and clinicians and academics.” They all seemed convinced too. After an investigative piece in The Wall Street Journal suggested her technology wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, Boies called for it to be independently tested. “There were several times when I was promised it was being done,” although it kept being delayed, he says. It has been pointed out that during this period, and before Boies cut his ties with her, Holmes was one of the guests at his 75th birthday party in Las Vegas. She even gave a toast. “I had a lot of clients that were there,” he says. “A lot of people gave toasts.”

Some people have suggested Boies’ work for Virginia Giuffre is part of an effort to restore his reputation, though, in fairness, he took her on in 2014. She had lawyers already, but “I think they realised she was going to come in for a lot of attacks”, he says. “She would really need a firm with a lot of resources.” Giuffre, an Australian resident who resides in Queensland, accused Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein of trafficking her to Prince Andrew. When Maxwell denied the claims and called Giuffre a liar, they sued for defamation. “Ultimately we had a very successful recovery against Ms Maxwell, financially,” he says. “Even more important, I think, in the larger scheme of things, we built an evidentiary record of the sex trafficking that, while it was sealed, it was something that was available to be unsealed by the government or… by the press.”

Eventually, Maxwell’s depositions in that case would be used against her as part of the criminal prosecution that now has her languishing in a Brooklyn jail, awaiting trial in November – a fact that must give Prince Andrew pause when he contemplates having to be deposed himself. Boies says this could probably be done in London; tapes of it could then be used as evidence in court, if it comes to that. Or the duke could try to settle the suit.

His chances of avoiding it entirely look slim. After the first hearing when Brettler, the duke’s lawyer, argued that the papers had not been properly served, Boies fired back with a memorandum, saying the process of serving a defendant was not supposed to be “a game of hide and seek behind palace walls”. Lewis Kaplan, the judge in New York, then ordered that the lawsuit could simply be sent to Brettler.

The duke’s lawyers also say Giuffre may have signed away her right to sue the Prince in a 2009 settlement with Epstein, which they are seeking to have unsealed. “It’s irrelevant,” Boies says. “It had to do with Epstein and certain people he did certain things with in Florida. Because it’s confidential I can’t really go into the terms of it, but… it doesn’t protect Prince Andrew.” It’s now been confirmed that court papers were served on September 21 and the duke has until October 29 to respond.

I ask Boies what he made of the duke’s infamous interview on Newsnight. “It was inexplicable to me why his advisers would permit him to do it,” he says. “The interview simply drew more attention to him and… the fact that he had no credible explanation. In addition, it put on display a level of arrogance and lack of remorse that was the opposite of what I would at least think he should have been conveying.” I imagine Boies watching it and rubbing his hands. “Oh yes, obviously,” he says. “No question about that.”

How will you do it? I ask. “Generally, what is the most effective is to just patiently go through what the facts are,” he replies. It sounds very reasonable, and also like a threat.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout