Grieve, play, live: Elizabeth Gilbert’s tumultuous life

A breakup, a new love, a death… a lot has happened in Elizabeth Gilbert’s life since Eat Pray Love.

When I tell a friend I’m meeting Elizabeth Gilbert, she stands up from her seat in the pub and gasps. Another shouts, “But I want to interview her!” No one else I’ve ever interviewed has inspired people to react the way they do. At a dinner the night before the interview, a woman I meet puts down her fork, grips my arm and says: “I ended my marriage when I read that book.”

“That book” is Eat Pray Love. A memoir written by Gilbert in 2006, it told the story of her divorce aged 34 and subsequent year-long trip of spirituality, curiosity, pleasure and self-discovery spent in Italy, India and Indonesia. It was read by 13 million people globally and turned into a film starring Julia Roberts as Gilbert and Javier Bardem as a man named Felipe — a pseudonym for Brazilian businessman Jose Nunes, whom she met in Bali, fell in love with and married in 2007.

Eat Pray Love is a bible on many women’s bookshelves. It spent more than 200 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list. I read it aged 23 and swiftly booked a trip to Bali on the turn of the final page. While I was there I saw so many Gilbert impersonators, I took a collection of stealth photos every time I spotted one. I have a picture of a cafe in the hills of Ubud where several blonde women in their mid-30s sit alone at tables, gazing out over a rice paddy field, waiting for their Felipe.

For many fans, though, “that book” turned out to be a mere gateway drug into the world of Elizabeth Gilbert. She has since written four more, done TED talks and a podcast series. She hosts “curiosity, creativity and courage” retreats with a friend, the author Cheryl Strayed, and now has an online community of 1.7 million that she communicates with on her Facebook page with updates, encouragement, wisdom and messages that begin with “Dear Ones”. She has become a modern-day philosopher on the subjects of love, life, death, spirituality, friendship and creativity. She represents a certain open-hearted, earnest sincerity that feels incompatible with modern, cynical sensibility and yet, evidently, many of us crave.

When we meet she is energetic, bright-eyed, elfin-faced and charming, despite having lost her voice. Her manner is one of Pollyanna-style enthusiasm, while also being decidedly forthright. I ask her to tell me if my questions are too nosy, as I know this to be an occupational hazard when you write a memoir and everyone talks to you like you’re their aunty. “I don’t have a lot of boundaries,” she assures me breezily. “But if I run into one, I’ll be certain you’re the first to know.”

This is good news, as I’m keen to ask her about the intervening years since “that book” was published, in which the plot of her personal life seems to have been as substantial as one of her novels. In July 2016 she announced on her Facebook page that she was separating from Nunes, describing their parting as “very amicable” and their reasons as “very personal”, after nine years of marriage. Two months later she revealed she was in a relationship with her female best friend, writer Rayya Elias, then 55, who had just been diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer. Elias passed away in January last year, with Gilbert at her side.

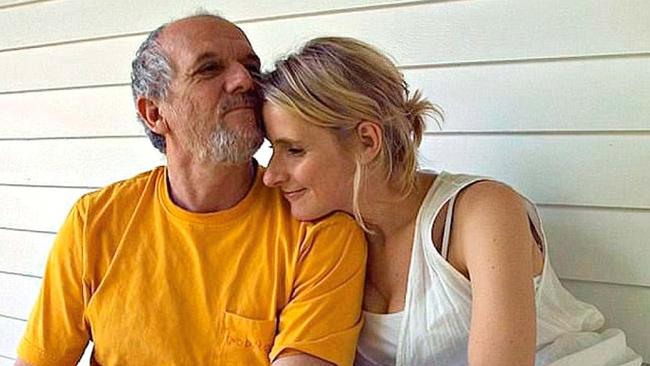

In March, a few weeks after we met, she posted a photo on Instagram of her head being nuzzled by a man named Simon MacArthur and her face is positively beaming with joy. The caption informed her Dear Ones that she was in love with a British photographer and “beautiful man” who had been a friend of hers for years and “even more touchingly, a beloved friend of Rayya’s”. She went on to say that he and Elias had lived together in London more than 30 years ago and “adored each other forever like siblings”; despite the relationship being very new, “his heart had been such a warm place” for her to land. She offered words of wisdom to “normalise” falling in love — while still feeling a “gorgeous loyalty to the deceased” — in middle age with a man, having previously been in love with a woman.

Gilbert met Elias in New York in 2000, when Elias was working as a hairdresser. “I have problem hair. When she met me, she said, ‘Oh dude, we’ve got to fix this Art Garfunkel ’fro’.” She said it wasn’t love at first sight, but she thought Elias was “the coolest chick in the world. There I was in my cardigan, The Atlantic tucked under my arm, and there she was with her heroin track scars, her two pit bulls and her ferocious defiance”. Elias was a Syrian-born musician, filmmaker, recovering drug addict and longtime character of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “She was the alpha in every single room she went into,” Gilbert tells me. “And it made me always want to be near her, because I felt the world was always safe when she was in it.”

The pair were hairdresser and client, then friends, then artist and patron when Gilbert encouraged Elias to write her memoir, Harley Loco: A Memoir of Hard Living, Hair, and Post-Punk, from the Middle East to the Lower East Side (published in 2013); Gilbert wrote the introduction. Then there was “about a five-year period” in which they “couldn’t find the word” for what they were for each other. “I didn’t quite know what to do with the fact that the most important person in my life was not my spouse. It was her,” she tells me.

When Elias was diagnosed with cancer, Gilbert realised, very suddenly, that she had to tell her that she was “the love of her life”, as she didn’t want Elias to die without knowing it. She describes the subsequent fallout as happening “swiftly and almost bloodlessly”, and there was a level at which “none of the people involved were surprised”, but that is as much as she can say without intruding on her ex-husband’s privacy. I ask her if she had been with women before Elias and she laughs: “I’m thinking of a line that is, weirdly, in the movie Coyote Ugly — ‘I played in the minors but never turned pro.’ I feel that that’s the most honest answer I can give. Not in any significant way, no. I didn’t give it a moment’s thought and I haven’t since. Nothing matters — personally, to me — less than that. I loved Rayya and that was it.”

Breaking up a relationship of more than a decade is a traumatic thing for anyone, but when it is a relationship that 13 million people fell in love with, I imagine it is even more complicated. While it was happening, did she, in any small way, consider what the disintegration of this marriage might mean to legions of women who had projected their own hopes onto her story?

“There are so many reasons I wanted that marriage to last, and not disappointing my fans was not on the list whatsoever,” she says. “Here’s what I think: if I owe anything — and I’m not sure I do — it’s as much empathy and grace as I can offer, and honesty. I love my readers, but I don’t think I owe them a f..king thing. And nor do they owe me a f..king thing. And what I mean by that is that my feelings are not hurt that out of the 13 million people who read Eat Pray Love, probably 200,000 of them read The Signature of All Things [her second novel, published in 2013]. If there’s something that I offer you and you want it — great. We are all here voluntarily in this relationship. You’re free to leave at any time, and I’m free to depart any time into any avenue I find interesting.”

Honesty seems to be the gasoline that fires up and powers every corner of Gilbert’s life. One of the most telling sentences in Eat Pray Love is the line (underlined in purple ink by my 23-year-old self in the battered copy I still have): Tell the truth, tell the truth, tell the truth. Her relentless truth-telling is admirable, but I wonder if it is not very exhausting, too. “Not as exhausting as lying,” she replies immediately. “If I’m depressed, anxious or beaten down, it is an invitation for me to ask myself where I am lying. Because, guaranteed, I’m lying somewhere. There’s an efficiency to telling the truth. Rayya said, ‘The truth will always be the last thing standing in the room when everything else blows up. And since it’s where we’re all going to end up, why don’t we just start with it?’ If there’s anything I inherited from her, it’s that. When I’m in moments of difficulty, I hear her saying, ‘Just start with it, babe. Just start with the truth.’ ”

I ask her how and when she chooses to share the truth of her private life online and she tells me it’s “intuitive”, which is why she doesn’t have a social media manager. “The very expression makes me want to put a cigarette out on my arm, I’m sorry.”

Gilbert grew up on a small, remote Christmas tree farm in Connecticut with few modern luxuries — I have heard her say in a podcast interview that she and her sister (novelist Catherine Gilbert Murdock) used to fight over who got to play on the typewriter. She was an avid reader and writer and, after obtaining a degree in political science from New York University, she wrote a short story that was published in Esquire (the first unpublished author to debut with a short story in the magazine since Norman Mailer) and became a journalist of long-form features for glossy men’s magazines. In the interim, between obtaining her degree and embarking on her journalistic career, she also did a lot of living — working in bars and travelling extensively, which she has part-credited for her curiosity about people and their stories.

She has just released City of Girls — a glamorous, sexy, compelling romp of a novel about showgirls in New York in the 1940s. It is an addictive story with vivid, brazenly drawn female characters that brims with fascinating historical details. The impetus for the book, she says, was “wanting to write about promiscuous girls whose lives aren’t destroyed by it. It’s really hard to find that book.” It is radical and refreshing to read and, I tell her, a reassuring reminder of the fun of female sexuality in a time when conversations on sex between men and women are understandably very grave.

“I’m a fanatic supporter of the #MeToo movement,” she responds. “It’s a long overdue expression of rage and conviction that is needed. But what I will say is that a great deal of the conversation is about consent — which is fundamentally incredibly important when it comes to sexual acts between men and women — but it is not the final story.

“There is something I believe to be even stronger and more fascinating than consent, and that is female desire. There is something about consent that can become very passive, where the dialogue becomes about a woman being approached by a man and being asked ‘May I do this to you?’, and her role is only to either concede or to deny. There’s this other force in the world, which is a heated female desire that goes out on the prowl, looking for something she wants and asking for it directly. When you see a woman standing in the fullness of her desire and pointing across the room and saying, ‘That, I want that,’ it’s not soon to be forgotten. This book is a celebration of that.”

The book’s verve and raunch is even more impressive when you consider she wrote it during a time of immense grief. The deadline for City of Girls was seven months after Elias died. “I’d already got an extension when Rayya got sick. But when I [asked for] another extension and my publisher said no, I felt a thrill and that was the first life spark I felt after she died. There was something within me that said, ‘I dare you to write a sexy, joyous, light-hearted book at this moment in your life. What have you got, Gilbert?’ ”

She moved into Elias’s house and completed the book there. “One of Rayya’s dreams was that she wanted to live with me while I was writing a novel,” Gilbert explains. “She wanted to be the novelist’s wife, to see me get up in the morning and go to my desk and work and read my pages. Sadly, it wasn’t possible for me to work on this book while she was dying, because her dying was a full-time job for both of us, so we never got to share that experience. When it came time to write it, I slept in her bed and I sat at her desk. That was my way of saying, ‘I wish we could have done this together.’”

While it is clear Gilbert is mourning a great, great love, she says that while she knows there is only one life she could have lived with Rayya, there’s only one life she can live without her now. This seems a profound realisation to have on the eve of a new decade (she’s about to turn 50). What does she think it might look like? “Oh, it’s an exciting life. For one thing, I get to carry with me this heart that has loved ferociously. I get to keep that for the rest of time. And I get to do a bunch of shit that she would have never done. Rayya was awesome and fabulous, but she was a coach potato!” she says. “This summer I’m going stand-up paddling in the Norwegian fjords — she would have thrown herself in front of a city bus before she did something like that, and I wouldn’t have gone off and done it on my own. And there are love affairs I intend to have. Love is not dead for me, passion is not dead in me.”

Love affairs to be had, fjords to be swum in, books to be written. Gilbert’s appetite for life in the wake of her darkest hour really is a thing to behold. She tells me that the author Ann Patchett, a friend, gave her some sage advice. “She said, ‘Liz, Rayya belongs to the eternal now. And some day soon so will you. And that’s true of all of us. You have an infinite amount of time to belong to the eternal with her. But you only have this tiny bit of time to have this experience as a human being on Earth. Don’t lose it by trying to merge with her now. Merge with this, what’s here, the people who are here, what’s in front of you. The weird, strange, heartbreaking thing of being mortal. Do that.

“The good news is that soon we’ll all be dead,” Gilbert laughs cheerily. “And we will all meet up later at some weird soul conference and look back on this and say, ‘Isn’t it hilarious, what we did? Wasn’t that f..king hilarious?’ But for now, it’s time to just do it. And do it fully. This moment of being human is not to be wasted.”

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert (Bloomsbury, $35.99)