Greta Scacchi: on my terms

It was in the missionary position, under yet another male star, that Greta Scacchi decided ‘no more’.

This story was first published in 2019.

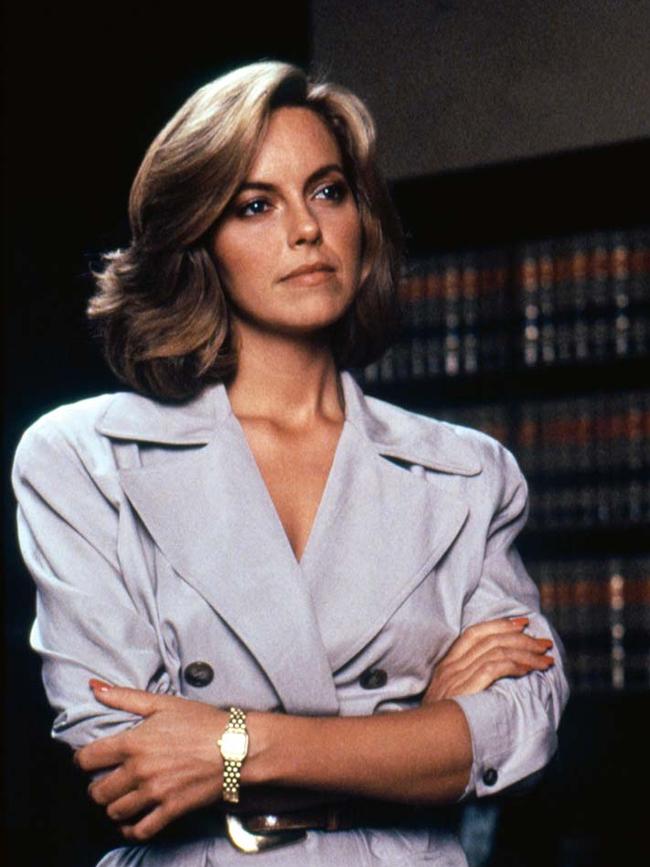

The camera doesn’t just love Greta Scacchi, it adores her. Ka-chick ka-chick it coos, willing her to love it back, stuttering and eager before the forcefield of her beauty. The first week of winter has Sydney in an icy grip. But inside a vast photographic studio in the city’s inner west, a familiar kind of alchemy is starting to heat up proceedings. Serious eyes; honeyed smile. The Italian-Australian actress, 59, tosses her hair and lifts her chin; if the camera had knees they would buckle.

This love is unrequited, though. A one-sided romance begun when Scacchi was a teen, modelling to put herself through drama school, waiting for life to begin. “Bum-crunchingly dull stuff,” she says now, dismissing the “weary world of modelling” with a wave. “I was just doing it as a means to an end.” She never loved the camera. She felt it stole from her. “The whole focus on image irritated me,” she says. “Being photogenic is what gave me my breaks but I was frustrated because how you look is not something that you really have much control of. It’s what you’re born with.”

Also beyond her control: the irresistible velocity of time, and how unusual it is, how downright heartening, to meet a middle-aged actress who seems not to care. The ethereal blonde who floated through the ’80s and ’90s as an unreachable male fantasy will live forever in films such as White Mischief and The Player. But Scacchi today is more earthbound. On the cusp of her 60th birthday, the mother of two has relaxed into her age and, on the right side of the #MeToo moment, found roles with a welcome complexity awaiting.

Roles like the one director Rachel Ward has handed her in the film Palm Beach, a Big Chill-esque comedy-drama set in the swanky enclave on Sydney’s northern peninsula. Scacchi slots neatly into a baby-boomer ensemble cast that includes Ward’s husband Bryan Brown, Sam Neill and Richard E. Grant as old friends gathering to celebrate a significant birthday. Her Charlotte is the film’s composed and steady core, a psychiatrist and mother producing endless chef-worthy spreads for a dozen house guests while contending with a riot of (mostly male) mid-life crises as well as her own cancer and its treatment. “She’s lovely as always but the role doesn’t rely solely on her appeal to men,” says Ward, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Joanna Murray-Smith. “The days when that was Greta’s sole, belittling function are gone.”

Ward, 61, is another blue-stocking brain whose God-given beauty blinded Hollywood honchos in her heyday. She also tired of the eye-candy roles and, while Scacchi turned her back on film to be taken more seriously as a stage actress, Ward headed behind the camera. “Nothing wrong with a beautiful woman,” Ward says. “It’s being limited to that is what irritates actresses.”

Many a star complains about their celebrity right up to the point that it fades, but Scacchi honestly welcomes the absence of the limelight’s leering glare. And, absent the strain and guilt of artificial preservation, she has, almost parenthetically, found a new kind of beauty. Her hair is shorter, darker; her figure belongs to the real world. She once toyed with the idea of cosmetic surgery but thought the people in the “before” pictures looked “nicer, warmer” and so the face that hosts that honeyed smile is untouched. Scacchi doesn’t love posing for photos. But she has flown out especially from her home in Sussex — the English county where the Milan-born actress spent much of her childhood before becoming an “adopted Australian” — to attend Palm Beach’s premiere at the Sydney Film Festival and it’s part of the deal.

So she puts her nice, warm face in front of the camera and the action awakens the muscle memory of a movie star. The camera ka-chick ka-chicks. Digital images flash up on the photographer’s computer screen and a small knot of stylists and assistants clustered around it inhale sharply. The pictures are stunning. Scacchi leaves the set without glancing at them. Not even curious. She doesn’t care what she looks like. She really doesn’t care. If the camera had a heart, it would break.

You may remember the way Scacchi looked inher youth. It inspired gushing geysers of alliteration: scorchy Scacchi, sizzling, sultry, sex-bomb Scacchi. It inspired former boyfriend Tim Finn to describe her as his “voluptuous muse” and Premiere magazine to crown her “the most ravishing actress alive”. And, at the height of her Hollywood fame, it inspired countless directors to ask her to take her clothes off.

Her breakthrough role in the 1983 Merchant Ivory epic Heat and Dust earned her a BAFTA nomination and a reputation for being relaxed about on-screen nudity. So she gritted her perfect teeth and stripped for scenes in Presumed Innocent and White Mischief, among others, until she reached the edge of her tolerance with 1991’s Shattered. “There I was, in the missionary position,” she would later say, “with the fourth famous actor in six months on top of me — Harrison Ford, Vincent D’Onofrio, Jimmy Smits, now Tom Berenger — and I’m thinking, ‘I just can’t do this any more’.” Even Helen Mirren, who now has both a damehood and an Oscar, has said that “nude scenes were the price you had to pay”, but Scacchi was naked so often she became a punchline.

From atop the crest of fourth-wave feminism, the casual sexism of the ’80s looks “laughable”, Scacchi says. “All those slightly soft-porny sex scenes that were considered compulsory in telling a story if you were the love interest.” Thankfully her lookalike daughter, Leila George, won’t have to endure it. The 27-year-old, from Scacchi’s tempestuous relationship with Law & Order star D’Onofrio, is an actress who last year starred in her first major movie, Mortal Engines. “I don’t think my daughter’s generation can be aware of what strides have been made in their own lifetimes,” Scacchi says, fending off jet lag with a second black coffee and the instant sugar hit of a Fantale. We are talking pre-photo shoot and her face is totally makeup-free above a roomy untucked shirt, dark jeans and, the middle-aged woman’s best friend, an artfully draped long scarf. “It was always my dream to be on the Fantale wrapper,” she muses absently before shifting focus back to her daughter, who was born in Sydney and now lives in Los Angeles. “She just kind of accepts that there is this presence of the female voice but it wasn’t there 20 years ago; it started to manifest itself just a bit after my time. And she’s of a generation that is so much more prepared to have equality and… not put up with shit. She’s not going to be prey to Harvey Weinstein, that’s been sorted. He and his types have had to pull their socks up. So I think the worst of it, all of that, is over for someone who wants to be an actor.”

For a while, Scacchi dodged the prevailing sexist agenda by working as often as she could with female directors. “There were this many in the ’80s,” she says, holding up a hand, fingers splayed. “And I worked with three of them: Margarethe von Trotta, Gillian Armstrong and Diane Kurys. I would work with the women on principle and find often that they were women who had to be very sort of brutish, or dictatorial; you could feel they’d had such a fight to get to that point that they were kind of scary! There was nothing relaxed about their approach.”

Working with Ward, who insisted on a crew that was 50 per cent female, was different. Ward has an easy self-assurance, Scacchi says, that allowed her to create a laidback set amid the sun-washed affluence of the peninsula. “I’ve known Richard E. Grant for a long time and I’ve known Sam [Neill] since my 20s,” she says. “With Rachel, I go back even further actually, to our modelling days. A lot of times between takes we’d put music on, music of our generation. It was so cool.”

There’s not nearly enough room on a Fantale wrapper for the details of Scacchi’s personal biography, an intricate, multicultural web of volatile personalities and perpetual motion. Greta and her identical-twin brothers Tom and Paul, who are a year older, were born in Milan, to Luca Scacchi, an Italian abstract artist, and Pamela, an English dancer. That union was explosive, “minestrone hitting the walls”, and her father sent the family to live in England when Greta was three. He would turn up sporadically, bearing gifts, but was feckless and unreliable and Greta’s parents eventually divorced. Her mother opened a dance school in Sussex, where Greta took ballet and tap classes, and eventually remarried, moving to Perth when Greta was 15.

From the age of eight, Scacchi knew she wanted to act; she’d fallen in love with the spoken word listening to her mother reciting Winnie the Pooh and classical verse at bedtime. And she wanted to be good. She appeared in plays at the University of Western Australia’s Dramatic Society while living in Perth and later won a place to study drama at the Bristol Old Vic theatre school in England.

“She was always committed to being an actress,” says Ward, who was moving in the same European modelling circles at the time. “I knew she was serious because she could have lolled about in front of the camera a bit longer and made good money instead of going off to drama school. I was thrilled as I knew I’d never get the job if she was in the room.”

Scacchi credits a rough-and-tumble childhood with giving her the tools to eventually navigate the “man’s world” of cinema. “I grew up with twin brothers and my mum and dad used to call us ‘the boys’,” she says. “We used to share the same clothes and I grew up feeling that I had exactly the same rights as my brothers. So, in that way, at a time when some girls would have felt they had to kowtow or be a little sheepish about their opinions, I didn’t have that at all. I was one of the boys. So I could say, ‘Ouch, you’re treading on my toe; I don’t like that’.”

Scacchi speaks four languages fluently and holds passports for Australia and Italy. She keeps a home in the Sydney beachside suburb of Coogee and, after a brief period in London warding off “empty nest syndrome” after her son Matteo, 20, moved to Sydney, she’s recently returned to Sussex. “Too many people in London,” she says. “Too many skyscrapers. Too much homogenisation.”

Complicating the tangled web of her biography further is the fact that Matteo’s father is Scacchi’s first cousin, Carlo Mantegazza. She and Carlo, who is three years older, had always been close but she was as shocked as anyone when, in 1997, their friendship turned romantic. Unions between first cousins are legal, but the media had a field day and her family, particularly the Italian side, was scandalised. With her son’s welfare top of mind, Scacchi has maintained a dignified silence about the so-called scandal. The only time she has spoken about it at length was in a 2011 interview for an English newspaper, in which she explained that Carlo made her feel grounded.

D’Onofrio had walked out on her when their daughter Leila was just six months old and Scacchi had spent the subsequent four years holed up in Sussex, not working, barely seeing anyone. That period of “total wretchedness… like having no skin” had left her emotionally raw. “I was looking for someone who would love me, support me and be there for me and my children,” she said then. “Carlo is a rock, a giver and a carer. By the time our son Matteo was born I had an extraordinary feeling of it being right.”

Pugilistic is not a word that readily attaches itself to Scacchi but right now she looks ready to rumble. She’s recounting an experience she had working with Robert Altman on The Player in 1992, the same year she turned down the infamous leg-crossing role that eventually went to Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct. She told Altman she would love to work with him but couldn’t “play the blonde who just does the token nude scene, I’ve done enough of that”. He agreed, but on the last day of filming changed his mind. “He said, ‘Who the hell do you think you are? I’m Robert Altman and I don’t see why I should pay for the fact that you’ve done a lot of lousy films with a lot of lousy directors. Now, get your ass on that set, take your knickers off and do what you were paid to do’.” Scacchi stood her ground and kept her clothes on for the sex scene with co-star Tim Robbins. Altman was forced to shoot from the neck up in an atmosphere “you could cut with a knife”.

As an added insult, Altman boasted during press for The Player that he was the first director to cast Scacchi in a film in which she kept her clothes on. The actress leans across the table that separates us, animated now. The decades-old memory still burns. “That was very, very painful for me, that he would promote a stereotype that was not true and yet it was one that I was having to fight constantly,” says Scacchi, who has since collected awards including an Emmy, an AFI Award and the Italian equivalent of a knighthood. “It was my sore point and he’d targeted it.”

Despite the scorn she pours upon it, her modelling phase had an upside. “Even though I saw a whole lot of exploitation [in the film industry] and I brushed up against it, I feel that I was always capable of holding my ground,” she says. “Starting to model at 17 and finding that the glamour of success is in reach and you’re handling it, you become less starstruck and less vulnerable to the excitement of maybe brushing up against stardom or glamour… That idea of, ‘Oh, he’s an important producer’ and ‘Oh, he’s paying me attention and what do I do now?’”

Here she pulls her knee back under the table and knocks it up against the underside so forcefully a coffee cup wobbles. Boof. “I was always ready to knee a guy in the balls if he dared to make a pass or do something inappropriate,” she says. “Not necessarily physically but metaphorically.” Smiles that pure-sugar smile. “That sort of strength comes from feeling confident that you have a goal and you’re going to achieve it and it’s going to be at a very high standard.”

Still, she confesses to a certain ambivalence. “I’ve not really been able to put into words my feelings about the whole #MeToo thing,” she says. “It’s hard when you have actually decided to participate as an actress in a, let’s say, still male-dominated world where you know very well the currency you’re using when you’re starting out is your looks. You know that your looks play a large part in securing yourself a job, in persuading these men that you’re right for a part. I’m not condoning in any way the inappropriate stuff, the harassment, but you’re actually using the fact that the guys are thinking, ‘I’m drawn to her, there’s chemistry, there’s animal magnetism’. You’re using animal magnetism as currency.”

In the end, the “tawdry stuff” put her off making films. “It was funny because the film work just kind of fell in my lap but it was stage work that I wanted to do and that took time,” she says. Following her rejection of Hollywood, she reinvented herself with West End roles including Bette Davis in Bette and Joan and, in a performance critics called “a revelation”, Hester Collyer in Terence Rattigan’s Deep Blue Sea. On the Sydney stage, she’s appeared in Harold Pinter’s Old Times, as Queen Elizabeth in Friedrich Schiller’s Mary Stuart and in David Williamson’s Nothing Personal. In 2013, she fulfilled an ambition to do Shakespeare with a role in King Lear at the Old Vic in London.

Theatre appealed because “I wanted to feel that I was holding the steering wheel”, she says. “On stage, the director has to persuade you of their vision because on the day they’ve got to hand it over to you. Whereas on film, so often I felt that something was being documented and then cut together and presented in a way that was not how I wanted to be — or how I had agreed to be — represented.”

There is a bedroom scene in Palm Beach . Scacchi is in it, along with Bryan Brown, a mass of high thread count sheets and a healthy dose of reality. Both actors remain clothed; the action begins and ends with the long-married couple spooning. Nothing “soft-porny” about it. “Bedroom scenes in life are often about things other than sex,” Ward says. “It’s where you come to download the day, to pick each other up, to comfort and encourage or to argue over one of the day’s insults or annoyances. Sex is a little more comical as you get older too, so we weren’t after anything raunchy and explicit.”

For Scacchi, that chaste and subtle scene has been a long time coming. It felt like a warm embrace of acceptance. “I did feel that it was quite a relief to get older and not have to play that one,” she says, adjusting her colourful scarf. “You know, the sexy one whose whole point of being there is to ride off into the sunset with a man. It’s a long time since I’ve had a decent role like this in film.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout