Fighting the fentanyl monster: a mother’s story

In the midst of an unprecedented opioid crisis, Lyndall Hobbs’ daughter developed a dangerous drug addiction. What could the Australian film director do to save Lola?

Fentanyl kills one American every seven minutes. Over 100,000 fentanyl overdose deaths were reported in 2022. This year’s figures will be higher. It’s a crisis of epic proportions turning kids into zombies – if they survive. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin and if you have an addictive bone in your body it gets you in its clutches, wrestles you to the ground, and doesn’t let go.

I know this because trying to keep my fentanyl-addicted daughter alive has become a full-time job.

I’m usually pretty good at finding some light in the dark tunnels but that persistent Aussie battler spirit has been sorely tested of late. Take one morning in 2021, when I received a call from Lola, then 33, begging me to come down to the Burbank jail to bail her out to the tune of thousands of dollars after she’d been slapped with felony charges for fentanyl possession with intent to sell.

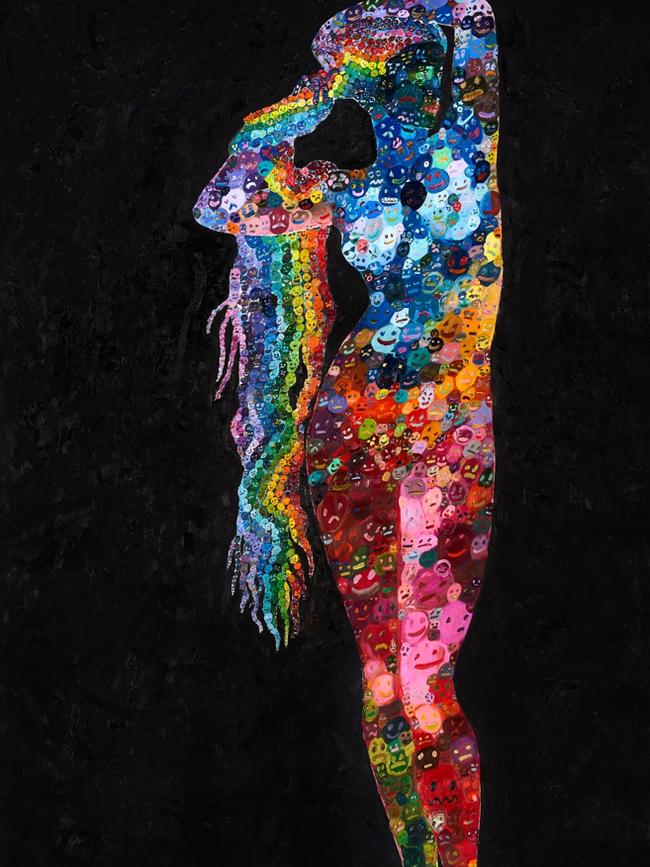

My flower-painting and baby-loving Lola went to private schools, including a stint at Loreto Kirribilli in Sydney, and she graduated with honours from the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. She is loved to pieces, was taught manners and went on to become a successful artist.

The past two decades have not been one continual train wreck. Glorious moments have transpired where my heart has nearly burst with pride. Lola found herself an extraordinary mentor – the late sculptor Robert Graham (husband to Anjelica Huston) – and, drawn to his sensibilities, she transferred from the Chicago Art Institute to Otis so she could be his devoted part-time assistant. Her graduate show was spectacular.

Lola’s empathy and kindness have few limits. When her beloved grandmother was dying, Lola moved in and slept on the floor until she died in her arms. I’ve been wildly impressed and moved as she played so creatively for hours with her adored brother Nick. She is crazy about kids. As she humbly greeted folks at a new show of her art over seven successful years, she was always self-effacing.

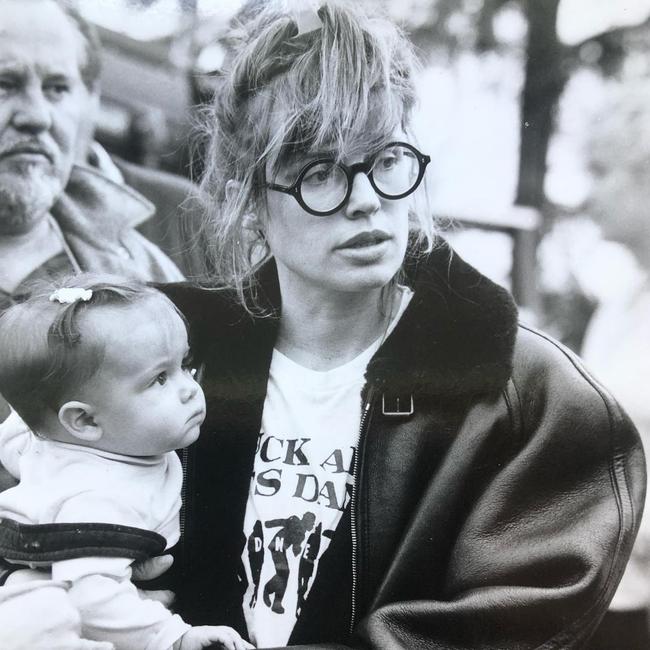

Back in 1999, US Vogue ran a piece I penned about my daughter, titled Daughter Dearest. It read: “In three months, my Lola turns 13. Her life is turning into a horror story. A terrifying experience. For me, not her. I may be a mother but I’m not a moron. I’ve seen Dawson’s Creek. I’ve listened to Eminem. First it’s sex, then drugs, then sex on drugs.”

I found her entry into teenage years upsetting, worrying if I was parenting well as a single mother in Hollywood. In high school Lola would attend “after-school rehab” for smoking pot. By the time she was in her mid-twenties she had tried heroin. And it did not stop there. Fast forward to the absolute shit show that’s been unfolding for the past eight years. I have found myself on the phone to bounty hunters, or tracking Lola down with the assistance of ex-navy Seals after she left rehab and went MIA for a month. When I’m not in Narcotics Anonymous or Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, I’m meeting interventionists, talking to lawyers, breaking up junkie fights, slapping dealers’ faces … all while trying not to get too involved. I’ve not truly heeded the well-meaning folks at AA who insist I should “let go and let God” or “detach with love”. I’ve been just as oblivious to sanctimonious friends’ talk of “tough love” and letting her hit bottom. Bottom with fentanyl usually means death. Am I an enabling, controlling pushover with no boundaries? Maybe. But stepping aside is not in my DNA. The thought of Lola overdosing and dying sends a sickening adrenaline rush through my body that nearly knocks me to the ground.

I married Lola’s dad, the gifted TV comedy writer Chris Thompson, in 1986 after a whirlwind romance. Chris had discovered Tom Hanks and created his first sitcom Bosom Buddies. We met three weeks after he’d left hospital after yet another cocaine binge, but he was sober then. Recently arrived in LA after ten years in London journalism, I went to dinner one night and was drawn to this gorgeous guy who made me laugh. Three weeks later I flew to Australia to see my family. He followed, we holed up in my Bondi apartment, the romance went into high gear. We flew to London, where he bought me a vintage diamond ring on Bond Street.

Back in LA – he’s still sober at this point – we had an engagement dinner with Jack Nicholson and Anjelica (yes, it’s name-dropping but these were our friends). Chris and I were desperate to have a baby and ten months after meeting, I was walking down the aisle, three months preggers, as gospel singers sang Waltzing Matilda in a celebrity-packed Westwood church. Chris had fallen off the sobriety wagon a month earlier, which was alarming, but I was pregnant and busy directing music videos, including one with Chaka Khan featuring Busby Berkeley-inspired choreography. Even if I’d been as well-versed in addiction as I am now, I would not have backed out. Still, it should have given me pause that he nearly missed the wedding after a drug-fuelled bachelor party hosted by Timothy Leary at Larry Flynt’s.

Outside a videographer recorded Tom Hanks, Richard Lewis and Bill Maher trying to out-joke each other as Robin Williams, Jack Nicholson and Lauren Hutton partied in the background. I finally watched the wedding video for the very first time recently – over three decades later. I laughed. And cried. I loved seeing my dad’s speech. But less touching and more in the spooky, prophetic category is a moment at the end with Chris, sober, and me standing next to him, grinning like a fool at my cute new hubby. He remarks straight to the camera: “You know, there was a black raven perched on our limousine when we arrived earlier. We’re probably going to have a devil baby and if I’m talking to my devil baby right now, you are pissing me off!” Devil baby? Could he see into the future?

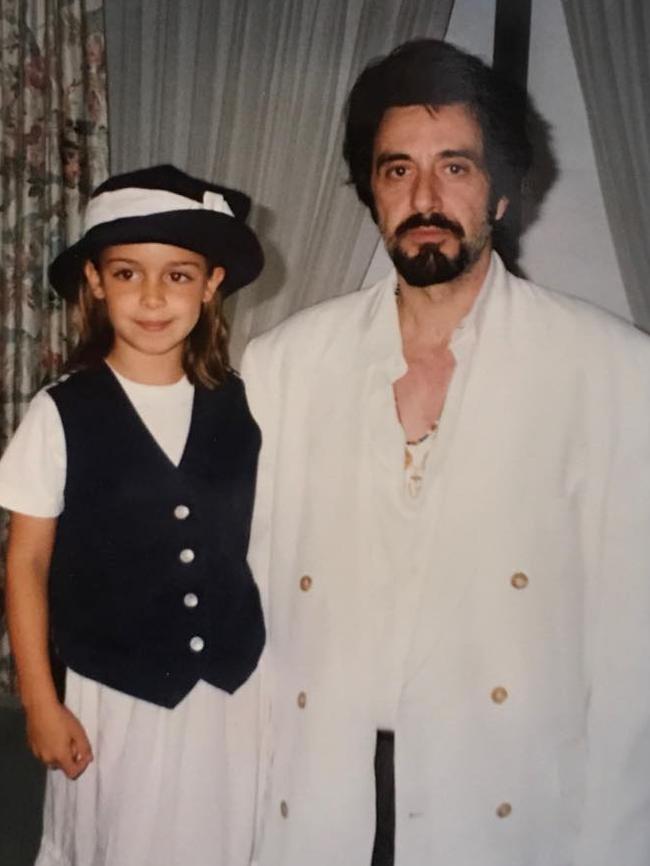

The joy was short-lived. He walked out for good one day when Lola was two. He was back on coke and booze. A year later, I began a seven-year “fling” with Al Pacino. It was not, as Lola is justifiably quick to remind me, the most stable time, as we bounced back and forth between LA and New York. I made sure Lola saw Chris, now diagnosed as bipolar, as often as possible. From an early age, she realised her dad had a serious alcohol and cocaine addiction and would likely be in and out of rehab the rest of his life. She lived in dread that her adored father would die. In later years, when he’d pass out on someone’s lawn or get arrested as a public nuisance, it was Lola he called to bail him out. He treated her like a friend, not a daughter.

The last show Chris created was Shake it Up Chicago, for which he’d discovered Zendaya and Bella Thorne. Chris was ecstatic, back in the saddle, but after two seasons he was fired from his own hit show for drinking on set. A year later he was homeless, broke and living in the tiny spare room of an old friend, Tim Curry.

In 2015, we were thrilled when out of the blue his old super-agent Ari Emanuel had a gig for him: reworking an Israeli comedy for Amazon. Chris wrote a treatment, ready for a final meeting. In turn, I told him Lola had started using heroin again.

Two days later, four days before his Amazon pitch meeting, he called several friends. No one was free to hit golf balls with him. So he cruised into a bar in the Valley, drank martinis and scored drugs. That night I received a call from an unknown number. I picked up and was told, “We cannot revive Chris Thompson.”

“Please keep trying,” I shrieked, so loudly that several dogs in the apartment building started barking. A long silence.

“Is he dead?” I asked eventually.

“Yes … I’m sorry,” muttered a tired cop.

The grief seeped into one’s very bones. Her entire life, Lola had feared her dad might die like this – and then it happened. Right then, I knew she’d never fully get over it. The night of his memorial, I looked in her bag and saw the drugs … the pipe, all the fixings. It was going to be a long and bumpy ride.

But Lola’s talent drove her on. She was soon a rather hot entity – one to watch. She was invited onto a new Bravo show, Work Of Art: The Next Great Artist. She made it to the second last episode but didn’t win. Lola, realising “it was vacuous and led to nothing”, got back to her art and was full of life. Until she wasn’t.

Huge mood swings. High highs, very low lows. She was diagnosed with bipolar. Exactly like her dad. Despite being high or maybe because of it, long nights of painting till dawn paid off. She was in group shows and then her first big solo show. The crowd? Cool and avant-garde. Some works glowed mysteriously under black light. Her first neon sculpture – of a mermaid – had folks fighting to buy it. Her sparkle paintings sold like hot cakes. The flower paintings, which were her real passion, vibrated with joy. People loved her sexy, well-priced nude watercolours. But Lola, still grief-stricken, wept daily, and used more and more drugs.

I took her first to doctors, then to grief therapists, before I dragged her to what turned out to be a shitty rehab near Palm Desert. Healthcare, especially for addiction, is all about money or good insurance. Lola had neither. Surrounded by barbed wire, this place resembled a women’s jail. Instead of therapy, clients had to clean toilets and wash laundry – which is fine, but when you’re peer-pressured to smoke meth at midnight by a “bunch of court-ordered crackheads”, you might start to call the joint iffy. She left.

Somehow in the chaos she’d let her great Obamacare health coverage lapse. I’ve made sure to pay it every month since then. Please bear in mind that having a bunch of rich pals doesn’t make you rich. Lola has not been cheap, but I have a few very kind and generous friends who have helped enormously along the way.

Next stop, another rehab, this one very expensive and suggested by Giles, the new boyfriend, a pot-smoking goofball who shared his art studio with her and was alarmed by her appetite for heroin. It was in Tijuana and they give you ibogaine, a psychedelic from the bark of the iboga tree – illegal in the US but unregulated in Mexico. The ibogaine trip can hopefully result in a diminished dependence on opioids. Lola stayed clean for four months.

Then, alarming things began to happen. While dog-sitting Giles’ apartment she started a fire. Her apartment then became a kind of trap house – she befriended Jane, a Mid-West college graduate, who introduced Lola to fentanyl, the cool new street drug that’s scarily easy to find when heroin is scarce. Giles and I were devastated. I researched fentanyl. It started in Chinese labs. Cheap, easy to make and up to 100 times stronger than heroin. Drug cartels love it, because it’s easy to smuggle. It was everywhere. Soon after, Giles left. He could take no more. In the fight against drug abuse by loved ones, mothers need to be fatigue-free – but weaker mortals, like boyfriends, drop by the wayside.

Then, as always is the case with Lola, out of nowhere something good happened that gave me hope. In 2017, Aussie fashion designer Lisa Gorman spotted Lola’s Instagram posts and asked to put her “exceptional art” onto clothes to launch her first US store. At the opening, models wore striking creations with Lola’s flower art printed on them. Eight months later Lola pulled off her best solo art show yet at the Lodge Gallery (run by Phil Noyce’s daughter, Alice) and in the glow of success, I saw my window of opportunity and begged her to go back to rehab. She told me she desperately needed help to fight the crippling self-loathing, grief and shame. Fentanyl made her feel light, happy and pain-free. On fentanyl she felt fearless.

In 2020, when Lola was 32, fentanyl led us to experience a humdinger of a night which involved me telling more spontaneous lies than I’d ever told and a celebrity friend hiring a private plane to get Lola out of California.

Early one morning, about 5am, a white SUV had crawled to a stop outside Lola’s shabby apartment block in LA. The motley crew inside her MacArthur Park drug den had finally settled down to the dark black sleep of fentanyl, after days of cruising, scoring, shooting up, shoplifting and hustling. In the bedroom I’d painted pale lavender just 12 months before, the floor was covered in drugs, drug fixings, stolen credit cards, driver’s licences, expensive stolen clothes, purses, shoes, magnets that allow you to shoplift without alarms going off, and a safe filled with money made from selling drugs.

Lola slept peacefully, while next to her, in boxers and requisite wife-beater, was Beau. He’d snuck in to “borrow” her iPad and watch Netflix. My account. In the other bedroom, Mack, a pimply, ferret-faced junkie, was shoving a printer under the bed after churning out five thousand bucks’ worth of counterfeit bills while his partner in crime, Bella, a blonde with faded tatts, was sprawled on the bed naked. Suddenly, there was a loud banging.

Mack rushed to the door, forgetting the golden rule in a trap house. Do not open doors. Check the camera first. But the metal grille was still locked. In his face were four scary-as-hell Hispanic gangbangers. One with a missing front tooth, known as Whitefolks, pointed a gun. “Yo, open the f--k up! Unlock this door now or I’ll blow your head off.”

The gangsters entered the apartment, found Lola and grabbed her wrist. She woke to see Whitefolks’ big ugly mug, just inches away. Naturally she was terrified that rape or death, or both, were imminent. But she was lucky. They wanted her money since she’d been dealing on their turf. She had about $8000 in her safe. She got up and quickly handed over the cash. My charismatic, generous-to-a-fault baby girl was now completely off the f--king rails, being held up by the notoriously violent 18th Street Gang. She was lucky they didn’t blow her head off for daring to deal on their turf.

I got a call from one of Lola’s frightened girlfriends (now dead, by the way) who filled me in about the gang visit and then, truly desperate, I called an old friend, the extraordinary Sean Penn. He thought an undercover cop friend could scare some sense into Lola. He suggested a dinner – he would bring friends in the rehab world, plus the undercover cop.

The next day, when Lola showed up unannounced, I made her a latte and calmly found myself telling her an unrehearsed pack of lies: I’d had private detectives casing her joint for over a week. They’d told me she was extorted by the 18th Street Gang and a snitch had videoed activities inside her pad. I continued the fiction: an undercover cop I’d found through Sean said her apartment was about to be raided. I told her Sean wanted to meet and help. Panicked, she disappeared to make calls while I dialled Sean to explain all the lies. He said he would send an SUV. I told Lola that Sean would meet her at her apartment so that she could get some belongings.

An SUV appeared in front of my building and she jumped in. Sean gave me his undercover cop’s number, so I could brief him, then he dashed to meet Lola – to the shock of assembled junkies who could barely believe it was Spicoli from Fast Times at Ridgemont High in the flesh. Finally, she was ready. Sean said, “Let’s go to dinner, meet my guy. He’ll be useful.” Sure enough, waiting at an old-school Westside Italian place were the undercover cop Joe, Sean’s girlfriend, and two other guys. Sean finally appeared and Lola followed ten steps behind, obviously anxious and ready to bolt. An ambush is an ambush.

Joe launched into his speech, saying she wouldn’t enjoy federal prison – which is where she would be going even for allowing counterfeit money to be produced in her apartment. He laid it on thick. Her only hope, he claimed, was to leave the state the following day and not be there when her apartment was raided. If she got herself to rehab, she would avoid jail.

I was already texting rehab admissions people. There was a bed in Tucson. Sean excused himself, then returned to say he’d hired a private jet to take her, the next day, to any rehab of her choice. I was gobsmacked, blown away by such generosity. I protested, but he said: “It’s done. But this has to be your decision, Lola. You’re a free agent.” A weeping, overwhelmed Lola nodded yes. Yes. It is a privileged, elitist tale. And it all worked. For a bit. She spent 32 days in rehab, and during this time when we spoke she sounded different – deliriously happy, proud of herself. Like Lola of old. Naive idiot dreamer that I am, I was somehow imagining the nightmare had ended. But on day 32, she made a silly joke to a therapist and was kicked out of the facility. I only heard about this 24 hours later, by which time she was MIA in Tucson.

She stayed missing for an entire month. I called hospitals, morgues and police stations.

It turned out that Lola’s pal Bella had flown to Tucson where they printed fake money, took fentanyl and shot up meth. Finally, she hopped a Greyhound bus back to LA. What followed was another three long years of hell as fentanyl dragged her down, down, down. No one who knew Lola could believe she was still alive. And still I hadn’t given up on her for a second. Because I knew the combination of mental illness and addiction drenched in shame are almost insurmountable foes. I had a front-row seat. I still do.

Lola wrote once: “It’s no small thing to feel perpetually out of sync with LA and sunshine, to feel a pain pressing on your heart and lungs that suffocates you some days. There was no relief till I found fentanyl. Dying cancer patients take it for pain. I was dying. From grief.”

Am I angry my daughter has continued as a homeless drug addict when I’ve offered constant help? Anger doesn’t begin to describe it. She’s put other people’s lives at risk. And her own. Every single day. Am I sick that I’ve spent countless nights tracking her down? Walking through Skid Row or MacArthur Park at dawn? Arriving at vile downtown hotels at midnight, screaming at employees, threatening to call the cops? Her friends, and even Lola, would finally laugh, incredulous that I always found her.

Was I devastated to be called to bail her out after being charged with a “dealing” felony? Oh yes. Should I have left her there in jail? Maybe.

Long, heartbreaking years of lawyers, meetings, more rehab, and always, another heart-stopping call to tell me she’s left. Years of misery. But I have infinite sympathy. She’s an addict. She inherited it and has it bad. And I’m one of the lucky ones. My daughter’s alive. I know there’s nothing to do but keep fighting for your kids. Nick and Lola are the loves of my life. Nick has suffered because of Lola.

In the time it’s taken me to write this, Lola has gone to rehab three times, been kicked out, got sober once, and then she slipped. I think ‘‘this is it” as she sounded enlightened and sober on the phone before I drove over to the rehab to visit. By the time I get there, she’s walked out with another addict and disappeared. Three days later after going to some grisly crack den, she’s wracked with guilt. But she’s alive.

I’ve finally embraced the fact that my life took a whopping detour. The days of being the youngest female on-air reporter in Australia and the UK, living with London’s hottest impresario, marrying one of Hollywood’s funniest comedy writers, dating a movie star for seven years or staying at Sandringham with my pal, the then-Prince Charles, are long gone. But I’m not a victim. I like to think of myself as a flawed, enabling, overbearing, micromanaging nightmare of a mother. And proud of it.

When Lola recently told me “Mum, you’ve saved my life,” it was all I needed to keep going and stay vigilant.

I dream she’ll finally get clean, make amends, keep painting, and help others in their recovery. I’ve written this in the hope it will help other parents and addicts. I hope she’s still alive by the time you read this. It could all change on a dime. The world needs no end of warnings. Because a mother’s love is not enough.

Postscript: Earlier this year, Lola spent four months at a rehabilitation facility in South Africa. She is now nine months sober after spending time in after-care in London, submitting to drug testing and therapy. She has begun painting again and has been made the first artist-in-residence at Petersham Nurseries. Her work is available via Instagram @lolarosethompson. Lyndall Hobbs says her daughter fears a return to LA – where fentanyl is cheap and available.

If you or someone you know needs support, contact Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. If you’re in crisis or feeling unsafe, please call 000 or Lifeline on 13 11 14.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout