Fiftieth birthday club: four strangers, one anniversary

Four strangers united by a common birth date, 50 years ago today. How did their lives pan out?

Every day is special to someone. A birth, a death, a marriage proposal, a declaration of war, a declaration of love: memories are forged across the calendar and for more reasons than there are days to fill it. Someone buys their first home on the same day that someone else is forced to sell their business. One person loses their job and another wins the lottery.

Some days will be remembered more than others, for reasons good and bad, but whether any day can be considered ordinary depends on your perspective. For the enormous crowds that filled the streets of Launceston 50 years ago today, the first Saturday of April in 1970 was the sort of once-in-a-lifetime occasion that will be long remembered, even if the exact date will not. The Queen, Prince Philip and their two eldest children were in town, and 30,000 people gathered to see them passing by, just days after half the population of Hobart provided a similarly warm royal welcome.

For a select group, today will always be special. For the 332,000 people born around the world on April 4, 1970, this day would be inscribed on birth certificates, passports, driver’s licences, wedding registrations and, eventually, death certificates. Some would go on to make newsworthy achievements; in regional NSW, cotton farmer Robert Stoltenberg and his wife Margaret celebrated the arrival of their fourth child and firstborn son Jason, who, within just 16 years, would be the world’s top junior tennis player. Exceptional, but also the exception. The vast majority of those born on this day, some 800 of them in Australia, would go on to forge quiet, comparatively anonymous lives, with varying degrees of joy, sadness, regret, fulfilment and even duration.

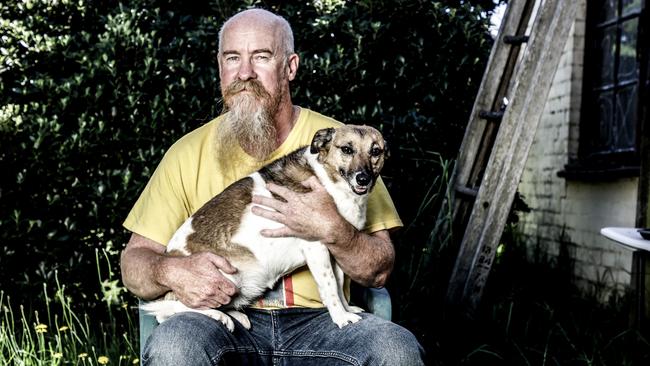

What makes a life satisfying? Career success? Money? The support of an enormous family? It’s an elusive mix but for Andrew Kleeberg simplicity is a vital ingredient. On a world scale, his aspirations have never been lofty. Growing up in Melbourne the youngest of four children, he fancied himself as a photographer or, inspired by his father who worked at a local television station, an engineer. But he never loved academia as much as making things or discovering his backyard. “I was an outside kid always,” he says in his quiet and considered manner as he sips an oversized coffee at a cafe overlooking Western Port on the Mornington Peninsula, his home for most of his adult life. “There’s more fun to be had outside: bugs, spiders, critters, birds. I think I was mowing lawns at about 11, earning pocket money.”

As a child he loved sport but had terrible asthma; by the time he was 15 it had eased and he could join his father and brother in games of squash. Apart from the time he hoisted himself on the clothesline only to end up crashing into the backyard shed, he was rarely in trouble. “I got my first speeding fine when I would have been 31.”

After school he began an apprenticeship as a radio technician with the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works but soon realised it had little future. “In about the third year you could see the new generation of radios were coming out with smaller circuit boards which you just replaced, rather than repaired. It started to become throwaway.”

By 1992, in his fourth year, his job was deemed to be redundant. He took 18 months off and moved back in with his parents, who’d left Melbourne for the Mornington Peninsula. At 24, “just to get money”, he started working at a local chicken processing plant. “In less than a year I became a trainer. And in less than a year again I became a leading hand, and in another year I was second in charge of the processing out the back.”

It was not so much a plan as an evolution. By then in his 20s, he’d often meet up with friends on weekends in Rosebud. “I was into machines and we all used to park across from the Mobil servo and just hang out around there, watching the traffic: Monaros and Toranas. Any night there would be up to 20 of us hanging around.”

One of those mates was dating a young woman, Kim, and she and Andrew soon became friends. In 1988, she introduced him to her friend Rebecca, who became his first love. “We hit it off. I’ve always been shy. But I just could talk to her.” When did he know she was the one? “Probably when I started thinking about it after I’d left that night,” he says with a shy shrug. Three years later they were married in the backyard of the Hastings home where they still live with two dogs and two cats, his beloved motorbike and 50 vintage lawnmowers. Their only child Emma, “a bright, clever daughter” is at uni and has just moved out.

After more than a decade at the chicken plant, and with a child and a mortgage, he picked up extra hours fixing things and at 38 he was offered an apprenticeship and retrained as an industrial electrician, still working at the same plant.

Planless and mostly happily, his life progressed. And then, as he hit middle age, his sister Susan, who’d had cancer for several years, died. In his 40s, he bought his first suit – for a funeral. “I know that everything ends. But I’ve lost quite a few people. I lost my best friend at 13. He got hit by a train in Ringwood. About two years ago, I lost another best friend. He had melanoma. I lost another friend about a year after that; he had thyroid cancer or something like that. I lost Dad: cancer. And my good friend Kim; she’s been gone eight months: cancer. It doesn’t pay to be my best friend sometimes,” and he laughs sadly.

This accumulation of loss has had a profound effect. “It’s made me think that a lot of things people worry about aren’t important,” he says. “You see people at work stressed out and you just tell them to sit back, it might be the last thing you do. If it’s broken, it’s broken. There’s no use worrying about it.”

After 27 years at the same workplace his weeks have assumed a gentle, familiar rhythm, allowing him to appreciate life’s minutiae. “On a Friday after work you sit in the back garden with a beer and think about nothing. Things like that: watching bees. And the dogs playing.”

He had planned to toast his first half century today with a quiet barbecue at home with his wife Rebecca and a couple of mates. With lockdowns and bans on gatherings, he’ll have to share the moment only with his wife. So how does he rate his life out of 10? “Nine,” he says without hesitation. “I haven’t taken any hard knocks. It’s been a journey.” He smiles. “I’m still here and I’m on a good wicket. I put the effort in and I’m winning.”

The time of his life? It can be tricky picking theprecise age that best sums up an individual’s impact. Those closest to Rock Davis, passionate cricketer and family-minded firstborn, will tell you that it was when he was 17 and still in high school, the almost-man who was already displaying the wisdom and even temperament for which he would be renowned. “He wasn’t perfect; he did wake at night. But he was always very calm,” says his proud mum Jan of the eldest of her four children, a solid baby (eight pounds, seven ounces) who opened his eyes in Parramatta Hospital on this day 50 years ago. “He was pretty easy, he smiled a lot.”

And so it was throughout his childhood and into his teens. “An old head on a young man” is how his brother Stephen, 16 months younger, describes him. The two boys shared a room at their home in Dundas, northwestern Sydney, through much of their childhoods, an arrangement that was mostly amicable, notwithstanding the horror movies Rock encouraged his frightened younger brother to watch before bed.

At the King’s School he was an average student, played guitar, had a small but tight circle of friends, and loved cricket. After dark he convinced his brother and their younger sisters Linda and Jenny to play the game in the hallway at home, using a table tennis ball and his Bradman signature bat, the bathroom door acting as wicket.

By his mid-teens, Rock was chatty and principled – he politely begged to differ with his high school economics teacher for failing his essay on hazardous investments, insisting that betting on horses was indeed high risk. With his smattering of after-school jobs delivering papers and mowing lawns, he earnt enough to buy a Dracula-themed pinball machine that still sits at his mum’s place.

Above all, he was sensible and reliable, ferrying his siblings when he gained his licence to social gatherings and to the new drive-through McDonald’s in Parramatta for the sheer novelty, in 1987, of buying burgers from the seat of his second-hand Mazda. He loved family but not parties, and apart from the time he sampled too much of the alcohol he was supposed to be serving at a friend’s grandfather’s birthday, he was no drinker. At 17 he was a mix of humility and confidence, neither seeking to be popular nor to impress others. He was, says his mum, “easygoing, nice to be with, trying to be helpful most of the time, and loving”.

At the start of Year 12 Rock moved into the family’s converted garage so he could concentrate on his studies, taking his stereo and his album collection (Australian Crawl, Hoodoo Gurus, Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison). He worked hard and his final school record described him as “a capable all-rounder, well liked and respected by peers”.

In the Christmas break, as they had done for years, he and his family drove north to Bateau Bay for their summer holiday in a friend’s caravan. It was a beautiful first night. After dinner Rock and his parents took a walk and talked about the future and his plans to study business at uni. The rest of the family remained in the caravan and watched a movie, Sayonara. Later, all six of them lay down on the grass and stared at the night sky.

In the first hours of December 27, Rock woke his mother. He was having trouble breathing. He’d had asthma since primary school but never anything severe. This was different. “He was having trouble and his colour wasn’t good,” says Jan. By coincidence the family’s doctor was holidaying nearby, so she and her husband, Rock Snr, bundled their firstborn into the car. “And by the time we got there,” she says, “he was dead.”

She pauses and stares straight ahead in the bright, comfortable home on Sydney’s outskirts where her adult son Stephen now lives with his own family. Her silence is mournful. What else can she say? Rock lived for 17 years, eight months, three weeks and two days. In his abruptly curtailed life there are countless missed markers: the family that his own family always imagined he would have; university graduation; an occupation. Later his mother found the phone numbers of two girls in his wallet. “He’d obviously met them somewhere and was intending to ring them. I don’t know anything about them. I was tempted to ring; I just wanted to know what kind of girl he liked.”

Rock Snr’s gone too now, but Jan and her children have kept the tradition of toasting Rock junior on his birthday at a special lunch. This year they’d planned to include some of his old mates, but social distancing ended that.

Rock has been gone now almost twice as long as he lived. “I realised afterwards that having him around always kept me in line – he kept me guided,” says his brother Stephen, now 48 and a father to his own son Rock. He begins to cry. His sister Linda moves closer on the couch and cradles him gently, thinking of their big brother whose wisdom lingers even as the duration of his absence lengthens. “Even though it’s been so long,” she says, “he still seems older than us.”

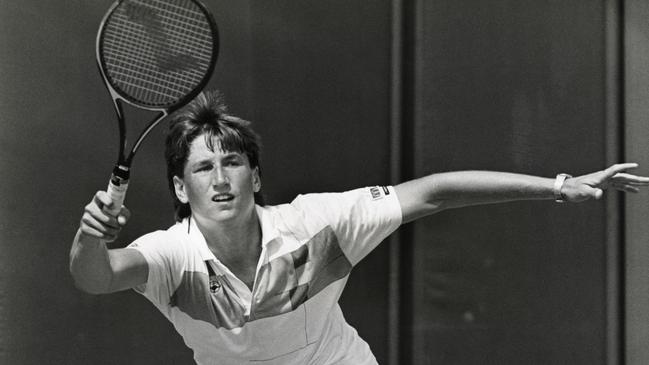

There is a randomness to life that can be kind but also cruelly haphazard. Because the year that Rock Davis died was also one of the finest of Jason Stoltenberg’s career. He was 17, had lived away from home for three years, was the world’s top junior tennis singles player and had just started travelling the world playing the game that would allow him to retire, with a handsome head start, at 31. It was an unlikely middle act for a life that began in what at times seemed like another world.

Growing up on the 1200ha cotton farm that his father managed near Narrabri in northwest NSW, his childhood was heavier on the ballgames that he loved than the school work that he found tiresome. He was a gifted tennis player and at 12 was asked to join the state’s tennis squad hundreds of kilometres away in Sydney. “I remember crying that I didn’t want to go.” Two years later came a second chance. “I made the decision at 14 to give up my family and my friends and my life to go down there and pursue this – I still don’t really know how, because my whole life flipped. I went from this really quiet laidback lifestyle to Sydney. I remember standing on top of this hill looking down at this new school and thinking, ‘Holy crap, what have I done?’ I probably get more emotional thinking about it now. At the time I just did it. Somehow subconsciously I knew that I had to go.”

In his 15th year he moved in with the family of another member of the squad – Todd Woodbridge, who would also go on to international success, and attended his same high school in Sydney’s south. Between tournaments, he completed his final two years of school over three years while living at the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra. Feeding coins into a payphone, he called his parents once a week.

Tennis revealed a new world. He was 15 when he travelled overseas for the first time to a tournament in New Caledonia. He joined the men’s tour at 19, bought his first property on the NSW central coast at 20, and a home in Florida at 24. For the 12 years that he played on the international circuit, his life followed a frenetic pattern of travel. The world was his workplace. He visited every continent except Antarctica.

At 21, he was sitting in the players’ lounge at the French Open when his life changed in an instant. “I turned around, I don’t know why, and I saw this girl walking past. I was drawn to her and I can’t explain why. It was like I recognised her somehow.” Andrea Strnadova had been a Czech champion junior player, and he spotted her again at another UK tournament the following week. “She just walked up and I started talking to her and we have been together since that day.”

His career flourished; at his peak he was ranked 19th in the world. He was a fine player with a good disposition; not once did he receive a warning for audible obscenity or racquet abuse. Then at 31, with a wife, a son and a daughter on the way, he quietly retired from the only career he had known. “You’ve got this rush of life and it’s on the go. You are going from hotel to hotel, that’s a really full-on life and then it stops. And if you don’t have a plan moving forward then it can become quite daunting. It’s difficult. The music stops. It goes quiet and there’s nothing,” he says from the kitchen table of his family’s expansive Melbourne home, with its raised tennis court and the English country garden that he lovingly maintains. “You get to 30, 35 and you’re done. Hopefully you’ve made enough money to have created a decent start to life… I wasn’t in a position to just pull up stumps and live on the beach for the rest of my life.”

So he forged a new career, for a time coaching world No. 1 Lleyton Hewitt, until the demands of this job, too, became too great. “I got to a point where I had to be a coach or a parent.” Later he coached an extraordinary teenager and future world No. 1, Ash Barty. Thanks to his sporting skills, he has often known success but never the stability of a more conventional career; his most recent role as head of men’s tennis with Tennis Australia is unclear, as are so many jobs right now.

His plans for his birthday today are simple, given the social distancing under which everyone is living: dinner and a movie at home with his wife and their two young adult children. “But it would have been low key anyway,” he says. Perhaps that’s not surprising. At 50, his values differ little from those he held when he lived on the farm with his folks. “My family were always very polite and always learned good manners. Manners and integrity and respect are the values that were important to me when I was young,” he says. “I feel like fundamentally I am still that person.”

So how does he rate his life? “It certainly hasn’t been easy. I have made sacrifices. There’s been a lot of good times, a lot of difficult times. I have got a wonderful family. I have worked really hard, nice life, kids are healthy.” And then, inevitably, he goes back to where he came from. “I was a country boy and giving that up was difficult.”

In geographical terms, Marisa Breitkopf’s worldis fairly contained. She was born at Canberra Hospital 50 years ago and has always lived in the vicinity. The national capital is where she was schooled, where she started her first job, met her husband, married and cared for her family. It’s where she took up smoking as a teenager, regularly broke her night-time curfew, and spent more time with her friends than studying. All three homes she’s ever lived in are here and apart from the occasional camping weekend or family holiday on the south coast of NSW, it’s where she mostly spends her leisure time. In half a century she has only left the country twice: once to the US in her 20s and years later to New Zealand.

Growing up, the Canberra spell was broken mostly at Christmas with visits to her mother’s family in Sydney, where a highlight was the array of available television stations (four) compared with Canberra’s two. “When we went to Sydney, Grandma had [kids’ TV show] Romper Room. It opened up a whole new world,” she says, smiling.

She lived her entire childhood in the same three-bedroom family home that her father Glen built in Canberra’s southern suburbs. Dining out was a rarity; for years, before her family discovered dine-in Pizza Huts, happy life events were celebrated around the family table. “Rather than going out we would have a special dinner night at home,” she recalls. “Dad would get dressed up in a suit, we would have on our Sunday best, the good china came out.”

She wrote to famous people hoping they would write back – she received replies from then prime minister Malcolm Fraser and the Queen’s lady in waiting – and after she and her younger sister Bernadette saved up enough money trading in empty soft drink cans, they bought a cassette recorder and audiotaped episodes of TV music shows Countdown and Sounds.

Gregarious by nature, at school she was a better friend and netballer than student. At home she was a mostly dutiful daughter. “My parents were very strict,” she says, chuckling now, of her disciplined but loving upbringing that included a ban on swearing. “I wasn’t allowed to go to many concerts. I had to be home at a certain time, Mass every Sunday come what may. If I was playing netball on Sunday morning, it took them a long time to come around to the idea of going to Mass on a Saturday night.”

The first time she remembers questioning religion was when she was 12, and her cousins were involved in a terrible car crash that left several severely injured. “You have to pray for them,” she remembers other shocked family members saying. “I can remember thinking, ‘What sort of God lets this happen?’ It didn’t make any sense.” Gradually, she began to rebel. She took up smoking. Started coming home late. “In the end I thought, ‘Well, what can they do? I’m working.’ They must have given up when I was maybe 20. It felt like forever.”

At school she had considered becoming a nurse, mostly because it didn’t involve a lot of study. “I was probably more the social girl at school.” She was accepted to study nursing in Sydney but could not immediately afford to live there. To earn some money, she attended a secretarial course and was hired by a Canberra legal firm. “After a couple of pay checks and still hanging around with my friends I thought, ‘No, I don’t think I’m going back to study’.”

A year later she moved to an administrative job at the Tidbinbilla tracking station and stayed for six years. It was there, through an office indoor cricket team, that she met her first boyfriend, a young apprentice plumber who had also grown up in Canberra. Jason Breitkopf was born one day after her at the same hospital – their mothers were part of the same mothers’ group.

They married in 1993, and only then did she move out (“I wasn’t allowed to live with my boyfriend”) to a house that was 15 minutes from his parents and less than 10 from hers. With three children, she did bookkeeping from home and in 2017 she returned to full-time work as an executive assistant in the public service, a job that, like so much in her life, pleases her enormously.

For years now she has lived in the same small street on Canberra’s outskirts, cultivating close relationships with her neighbours. The joint party she had planned with Jason has been shelved (“I sent out a message that said, ‘We’ve decided not to turn 50 this year’”). She once thought about living elsewhere. “But I had my friends and family here. I started working, then I met my husband. Life just kept going and everything was working out,” she says, and, as she so often does, smiles broadly.

With a touch of serendipity, and without having overly planned the future, she is proof that happiness can thrive regardless of the size of your world. “I don’t worry about what may happen too much. Just take one day, see where it goes,” she says. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do, so why not have kids and be happy? And this is the way it’s worked out. I love my life. I’ve got a great husband and a great family. I look forward to growing old.”