‘Fearless’ and ‘ferocious’: the making of Sharri Markson

She’s renowned for her tenacious journalism, having just landed herself a plum new gig. But Sharri Markson has a remarkable personal story of her own.

Sharri Markson had just vomited in a bin. She was on deadline for one of the most powerful stories of her career – a front-page exclusive that would lift the veil on the culture of sex and scandal in Parliament House long before Brittany Higgins came forward – while also crippled with food poisoning during the early stage of pregnancy. Yet despite all this, within hours Markson had shaken the foundations of government with a Daily Telegraph scoop, revealing that then deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce, a married father of four, was having an affair with his media adviser. Vikki Campion was seven months pregnant with Joyce’s child when the newspaper put her picture on the front page.

“I had been dealing with the food poisoning that afternoon and a barrage of calls from the editor while throwing up into my bin in Parliament House,” Markson recalls. “I didn’t even have time to go to the bathroom to be sick. I went to hospital at about 3am for medication to stop me vomiting and then went to Channel 7’s Sunrise studio at Parliament House to defend our story.”

Defend the story? Well, yes. “Later that night the front page, garnished with the headline ‘Bundle of Joyce’, started going viral on social media,” she explains. Her peers in the press gallery and some in the wider media began to attack the story. It was, they argued, none of the nation’s business. So Markson went on television to explain the implications of the scandal. “I never imagined I’d have to defend it – that journalists could actually think it wasn’t in the public interest.” She still shakes her head, even five years after the fact.

When Markson, in subsequent days, revealed that Joyce had used his position to find other jobs for his girlfriend within the government, and the then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull instituted a ban on relationships between staffers and their bosses, the validity of the story was beyond question. Joyce ultimately stepped down from his post and a litany of stories about intra-government affairs would follow in the coming years. But the day Joyce called his press conference, as reporters in newsrooms gathered around TV screens – a moment that should have been vindication for Markson – she was at home, recovering from the miscarriage of that very early pregnancy. And writing another front-page story.

Critics, rivals and supporters agree Markson is an extraordinary journalist. Possessing a tenacity and hunger for a scoop, the 38-year-old has been variously described as “singular”, “fearless” and “ferocious”.

Starting as a copygirl at the Sunday Telegraph at the age of 16, she was appointed the paper’s chief of staff at 25. After two years as news editor at Seven News (where she won a Walkley award for reporting an exclusive cabinet leak on a deal between the NSW government and ethanol producer Manildra Group), she became editor of the venerated women’s magazine Cleo at age 28, sharpening the focus of the title renowned for its centrefolds so that it routinely led the news agenda. She would become the first female federal political editor at The Daily Telegraph, breaking the Joyce story as well as exposing the revolt brewing within the Liberal Party that would end with Malcolm Turnbull’s downfall. As Investigations Editor at The Australian Markson revealed allegations of drugs and domestic violence against Sam Burgess by his former wife and the cover-up of the football star’s behaviour by the National Rugby League.

“The country needs hard, fearless journalists”

Next week, she steps into a prime time nightly spot at Sky News Australia. It was the slot earmarked for Chris Smith before he was stood down by the network for alleged drunken misconduct.

“Oh f..k”. This was, says one former Canberra ministerial staffer, the usual response to the news that Markson was pursuing a story with his office. Once, a newspaper editor discussed with a sitting premier the intention to install Markson as a political correspondent at Macquarie Street. The response was: “Don’t do it. Please.” Markson had already done a stint at NSW Parliament years earlier. NSW Treasurer Matt Kean, who has known Markson since 2005, says: “She’s forensic, she’s fearless and she’s at her best when she’s pushing the envelope – and I say that as someone who’s been on the receiving end of the ‘Sharri Markson treatment’.”

Former media adviser Lachlan Harris, who worked for then prime minister Kevin Rudd, says: “There were two people in Canberra I never wanted to go up against – Laurie Oakes and Sharri Markson. We’d have regular calls with ministerial press advisers to run through what would be making the news, and if someone mentioned Markson was on a story there would just be this deathly silence.” He adds: “Look, she is relentless, she’s tough and she’s got a hell of a nose for a story. We didn’t always align on everything but the country needs journalists that are that hard and fearless.”

She has also been subject to frequent personal and professional attacks by rival media. When she wrote a book investigating the origins of Covid,What Really Happened in Wuhan, published in 2021, which examined the prospect of a leak of the virus at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, she was denigrated by rivals at The Sydney Morning Herald and The Guardian. They scorned the premise of the book, claiming the prospect of a lab leak was a conspiracy theory. By the time she had finished the book, which became an international bestseller, US President Joe Biden’s probe had declared the lab leak “plausible” and the World Health Organisation had walked back its earlier opposition to the theory. For a subsequent Sky News documentary on the topic Markson secured an interview with Donald Trump – she remains the only journalist working for Australian media to interview the former president. She used the opportunity to calmly but firmly question him over America’s support of dangerous experimentation on coronaviruses in China. It’s been watched 13 million times on YouTube.

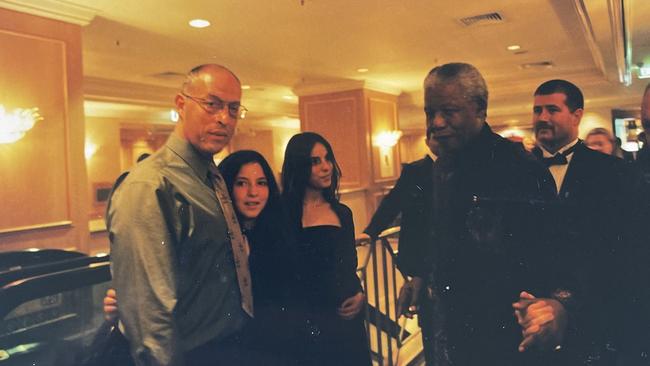

Markson’s cool demeanour opposite one of the most intimidating figures in world politics is not all that surprising, as it wasn’t the first time she’d spoken to an American president. From the 1980s to the early 2000s, the biggest name in celebrity publicity in Australia was Markson Sparks! – the firm her parents, Ro and Max Markson, founded in 1982. Ro had emigrated to Australia from South Africa on her own at 21. Max came from the UK on holiday when he was 21 and never wanted to leave. In the early days they had no money and fewer connections, but from those origins the pair created a machine. Sharri and her younger sister Rikki were introduced to some of the world’s most famous and powerful individuals.

Markson met former UK prime minister Tony Blair, and South African president Nelson Mandela. And in 2002, the then 18-year-old Markson spent a sunny afternoon with Bill Clinton onboard a boat on Sydney Harbour; while picking at a fruit platter, the former US president lamented to her that he had been unable to bring peace to the Middle East. “He said it was his greatest regret from his time in the White House,” she says. It was one of the highlights of a childhood surrounded by big names. “Ita Buttrose was at my bat-mitzvah,” she says casually. And with slightly more enthusiasm: “Chubby Checker taught me to do the twist in our family’s living room”. When it comes to clients and contacts, the Markson family rolodex was virtually priceless.

Was all this the making of Markson? Well, sort of.

She says she was infected with curiosity as a kid, when she spent Saturday nights driving around with her power couple parents, dashing into petrol stations to buy the first editions of the Sunday newspapers. When she began working in a newsroom while still at high school there was an immediate connection. “It was just such an enormous privilege to see what would be making the paper before anyone else,” she says. But she started from the bottom, fetching McDonald’s for hypoglycaemic sub-editors and collecting editors’ dry cleaning before she was promoted, after a few years, to write about cars. “The only job they had at the time was writing for the auto section. I just took it.”

And she always kept family and work at a wide distance. She pointed her career in the direction of politics and investigations and away from her parents’ business. She has not spoken publicly about her upbringing until now.

She had a falling out with her father that lasted for more than a decade after the breakdown of her parents’ marriage – an event covered in painful, sensationalist terms in the tabloids. “It was a tricky relationship for a while but Max is now a wonderful father and grandfather,” Markson says. “He loves babysitting the boys.”

Her mum, on the other hand, has been there through it all. They have always been “extremely close”, Markson says. “There is no bigger supporter. I can rely on her for anything. She has, and continues, to always be there for me.”

What all that celebrity exposure early in life did give her, she says, is the benefit of never feeling starstruck. How did it feel to be around all those famous people? “They’re just people. I guess I met them and saw them in situations where there is an element of vulnerability – worried or focused on how they’ll be received by the outside world.” Power, fame, just doesn’t faze her.

Markson was a shy child, although she has no qualms asking uncomfortable questions on camera. She has appeared on TV alongside red-blooded stars of conservative America such as Tucker Carlson and Steve Bannon. Having grown up watching her father – Australia’s most well known celebrity agent – spin for a living, she took the opposite route. In her down time, she paints still-life. She’s also a vegetarian (for ethical reasons).

In 2019, at the annual federal parliamentary knees up – Canberra’s Midwinter Ball – she accepted an award for her groundbreaking work. “All of this,” she said, gesturing around Parliament House’s Great Hall, at the audience of friends, foes and politically adjacent gawkers, “this all pales in comparison to my greatest exclusive – my son Raphi.”

That “exclusive” is today sitting in front of her singing Do-Re-Mi and asking her to pass the Smarties. The pair are baking cookies together for his 4th birthday party. Except Raphi is the one calling the shots. The apple has not fallen far from the tree. He is correcting her lyrics while they bop around her sun-drenched kitchen and open plan living room, where the walls are lined with overstuffed book cases of political memoirs, cookbooks and family photos.

She is looking forward to the Sky News gig, in which she hopes to garner a new audience with her investigative work. “I’m looking forward to breaking a story on Monday and following the developments of it over the week. That’s the great thing about TV.” There’s a mix of excitement and trepidation as she prepares to return to work. There’s been another “scoop” – her baby, Harley, now seven months old. As the cookie production line rolls, he’s dozing off in the arms of his grandfather.

“She’s an enigma,” says Markson’s former editor and long-time friend, Christopher Dore. “When it comes to pursuing a story she is ruthless, single-minded and obsessive. In life she is one of the most compassionate humans I’ve ever met, big-hearted and loyal. She is mis-labelled, misunderstood and constantly underestimated.” She is, he says, “utterly apolitical, open-minded and fair”.

Markson credits Dore for shepherding her through some of the biggest stories of her career. He reflects: “Working with Sharri can be a white-knuckled ride as she has what too few modern journalists, more obsessed with being popular, possess: no shame. No question is too embarrassing to ask, no story is too difficult to pursue and no public figure is too powerful.”

“There’s a mystique around Sharri,” Financial Review journalist Aaron Patrick adds. He was there when she was briefly detained during a press trip to Israel for interviewing Syrian resistance fighters. “That hit the headlines before we even got home,” Patrick recalls. “The coverage was water off a duck’s back.” It’s that attitude he believes has set her up well for a hard-hitting career.

Lachlan Harris speculates that she has a future in journalism in the US. “When she started appearing on the major US cable channels with her work around Covid, you just knew some people were thinking, ‘What a great thing for a young Aussie reporter to appear [on such high-profile shows],” he says. “But for those who know her, know her ability and her work ethic, we were like, ‘What took them so long to find her?’”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout