Evan Hughes reveals partnership with art dealer Tim Olsen

Evan Hughes, son of the late art dealer Ray Hughes, opens up about their tempestuous relationship and his plans to shake up the art world via a bold partnership with another scion — Tim Olsen.

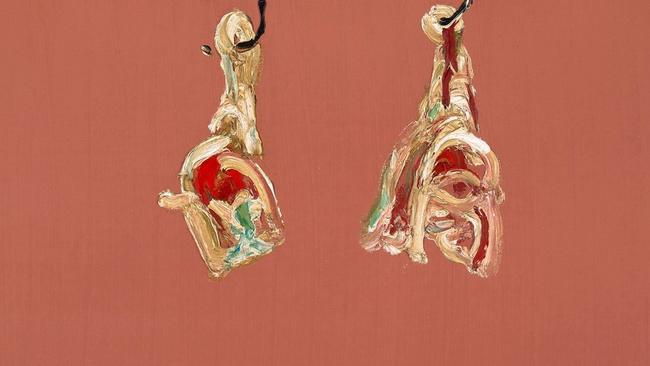

If he closes his eyes, he can picture them still, in visceral, unnerving detail. Legs of lamb virtually writhing on meat hooks, more dead carcass than food. Many consider Lamb, an oil by master Australian expressionist Fred Williams, one of his minor works. But Evan Hughes and his dad, the legendary Australian art dealer Ray, adored it. “There was something about it,” Evan says. “The way it was painted: the thick impasto where the sinew and bone push through the fat.” Then Ray Hughes died, and the something about it was death.

“I had to sell it,” Evan, 37, says. “One of my favourite paintings in the entire collection by my favourite Australian artist and I couldn’t own it anymore because every time I passed it, I had a pang of deep loss.”

It’s been five years since the elder Hughes – maverick Sydney gallerist, bon vivant, loyal champion of homegrown artists – died from respiratory failure at the age of 72, and the story of Lamb is instructive. It shows father and son shared a love of art that was deep and pure, untroubled by popular trends or commercial concerns. It shows father and son, for all the tumult and rebellion that marked their relationship, were more alike than different. And it demonstrates how greatly the life of the son has been shadowed by the immovable legend of his father.

Time has finally released Hughes from his mourning. He still can’t stomach Lamb, but for the first time since the forced 2015 closure of the celebrated Surry Hills gallery he ran with his dad, he’s ready to get back into art. “Dad was right all along: you’ve got to do what your passion is,” Evan says. “And I think it took me five years after he died to learn that. As a young man going too fast, I had all of that resentment that young, ambitious, arrogant men have, that the older generation couldn’t possibly know better. Well, I’ve grown up a fair bit now.”

The catalyst for the humbling of Evan Hughes was the disappointing conclusion to what he calls his “quixotic political adventure”. In 2016, he took on his former political hero, Malcolm Turnbull, as the preselected Labor candidate for the seat of Wentworth. Campaigning on issues such as same-sex marriage, the environment, public education and healthcare, he failed to see off the then prime minister. “I was trying to tell the public of Wentworth that, actually, the Malcolm Turnbull we all fell in love with was the one we’d quite like back,” he says. “Malcolm really was a progressive vision when I was growing up, with the work he did on the republic. Malcolm and Paul Keating were, I guess, the two political gods I had.” He takes a rare pause. “Well, one’s clearly a demigod; sort of like Hercules and Zeus, maybe.”

Evans, wearing bright purple pants and a pocket square, is outspoken and expansive. He’s had enough of politics (“Neither party’s making anyone happy”) and thinks the comfortably numb Australian art world is due for a shake-up. “When a country thinks of culture as something for the cocktail party set, that’s when the society is broken,” he says.

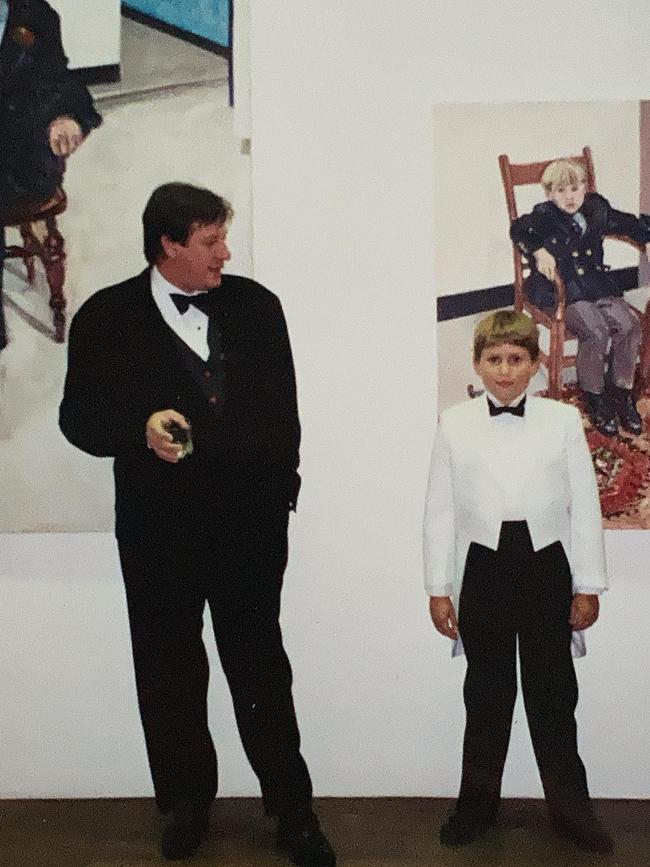

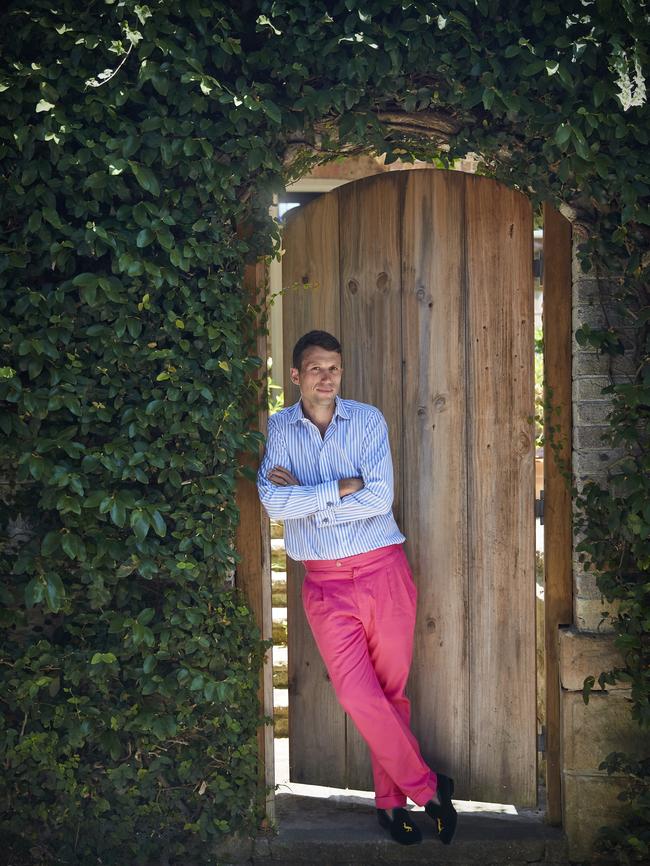

That’s why he’s decided to embark on a partnership with a man he’s known since childhood: art dealer Tim Olsen. The 60-year-old Olsen – son of another legend, Archibald Prize winner John – runs Olsen Gallery in Woollahra, and is keen to host works from the Hughes collection, currently in storage. “The thing I’m most looking forward to with Tim is having a mate that I can talk about art ideas with and go to see studios with,” Hughes says. “Because I know he is the same as me: he genuinely loves artists, and genuinely loves the work they make.”

They are planning a show for early next year, and Olsen says to expect the unexpected from the pairing. “I would like to work with Evan towards doing things that have a very cross-cultural and diverse scope, but still have a place in art history,” he says. “When you’re not bound by a particular school of thought, that opens you up to doing lots of interesting things.”

An unseasonably chill wind invades the atrium of the cavernous Surry Hills building that the elder Hughes shrewdly purchased in 1987 when he moved his expanding collection from Brisbane. A tram rattles past the window. The Ray Hughes Gallery (later the Hughes Gallery) was home to a wide range of Australian and international art, from cutting-edge Chinese paintings and African art to lyrical William Robinson landscapes and the contemporary art of Del Kathryn Barton. The boozy long lunches held upstairs each week were legendary.

This is where Evan grew up. In the decades since, the inner-city patch, metres from the late Brett Whiteley’s studio, has gone from the sketchy preserve of junkies and bikers to something of a cultural hub. The building Evan inherited now houses record company BMG Australia and the advertising agency Special Group.

A third tenant is the ghost of his father. “For as long as I can remember, Ray would be sitting under those stairs over there, conducting his empire,” Evan says. “You know, screaming at staff, telling gauche Eastern suburbs people to f..k off. We always had a table and chairs set up and after noon, there’d be a fairly good chance that if you were a young artist and wandered in, you’d be offered a Fourex and asked to sit down. Ray had more time for young National Art School painters than he did for investment bankers.”

“When a society thinks of culture as something for the cocktail party set, it’s broken”

An only child, Evan spent much of his boyhood travelling the world on buying trips with Ray: Papua New Guinea, Africa, China and Europe. (His father and mother, literary agent Annette, split when he was in primary school.) He has a degree in art history from Cambridge and was working at London’s Mayor Gallery in 2007 when the global financial crisis hit. Evan returned to Sydney to help his father, whose health was deteriorating, grapple with a spiralling art market, and remained co-director of the gallery until it closed.

For a while, Evan dabbled in private equity and is currently a researcher at Sydney University, focusing on Australian cultural diplomacy. He’s also writing a book about soft power, quite magnificently titled The Arts End of the World.

He describes a tumultuous relationship with his larger-than-life dad, beset by periods of estrangement and reconciliation. “We had such a tense relationship towards the end that I was relieved I actually got to sit with him on his deathbed and have ‘the moment’,” Evan says. “He was out of it when I said to him, ‘I don’t do great humility, Dad, but I’m really sorry for being such a f..kwit and, while you’re unconscious, I accept your apology too.’ Anyway, the next day he was still alive and he said, ‘Look, I heard it all and I agree with all of that.’ I think that was as close as we came to apologising to each other. But we finished on good terms.”

Evan, who lives in Sydney’s Paddington with his wife Kate, their children Harry, Teddy and Adelaide, and an American poodle named Jackie Onassis, inherited the passion of his father to unearth intriguing art and introduce it to the world. He believes in the future of dealer art galleries in an age of technological disruption, of algorithms and Instagram sales. “The partnership with Tim is going to be about the innovations of what dealing’s going to be over the next 10 years,” he says.

“I think times are going to be tough. Not to say I’m a recession specialist, but I know that you are required to work twice as hard. One of a dealer’s jobs is to remind art collectors that art’s a necessity of life. And that sounds ridiculous, but only to people who have never lived with it. Paintings change your life; they change your mood. They give great joy and energy when you’re suffering. And I’ve known that; I’ve had incredibly emotional responses to the art I’ve owned, related to things happening in my life.”

Evan Hughes on the cost of living crisis:

“I think times are going to be tough over the next few years. There are going to be people living in $4m or $5m houses that are highly leveraged and I think they start to lose some of the luxuries in life.”

Tim Olsen on his relationship with Evan Hughes:

“He’s like a brother to me. Evan and I were fortunate enough to grow up in an environment where we developed an eye vicariously, which is an education you can’t get in art school. With our combined forces, and our lineage within the art world, I think we are going to do some really interesting things.”

Tim Olsen on Ray Hughes:

“What I always admired about Ray was the eclecticism of what he did. I’m particularly interested in the international artists because I always admired Ray’s courage to show international art in a very parochial country.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout