Eulogy for Peter Krien, night editor at The Age

Two men on a very different journey with prostate cancer - and a poignant twist in their story.

A couple of months before he died, my friend Peter Krien and I were sitting together at an outside table at a cafe in Melbourne’s St Kilda. It was one of our regular meeting places, but not the only one.

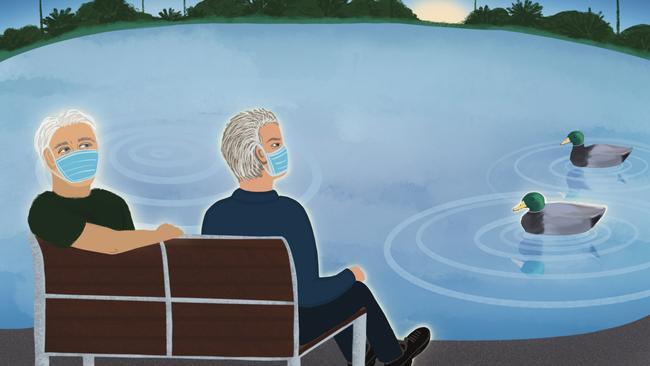

During the pandemic years, we would meet at the St Kilda Gardens. Even during the strict lockdowns, when we were allowed an hour a day outside, we would meet by accident in the gardens and sit on a bench by the lake, masked and as far apart as we could sit, and watch the ducks glide over the water. We would talk and then watch the ducks in silence.

Sometimes we sat there for more than the allowed hour of escape. Two elderly law-breakers we were, and we figured that if the police came by, we would plead old age and a certain vagueness. The police, sadly, never came by, sadly because we thought – Peter in particular – that our encounter with the police would make a nice little story which he would publish on Facebook with a photo of the police leading us away, hopefully in handcuffs.

We were not demented – well, Peter certainly was not. In the years after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, I think Peter lived more urgently and more vividly than anyone I knew. The pandemic did not force him to retreat from life, like it did many people, especially people like Peter who were older and had medical conditions which made avoiding Covid a matter of life and death. He was uncowed, if not unafraid, a big man still, living passionately and defiantly, the world as intensely interesting as it had always been, perhaps even more so.

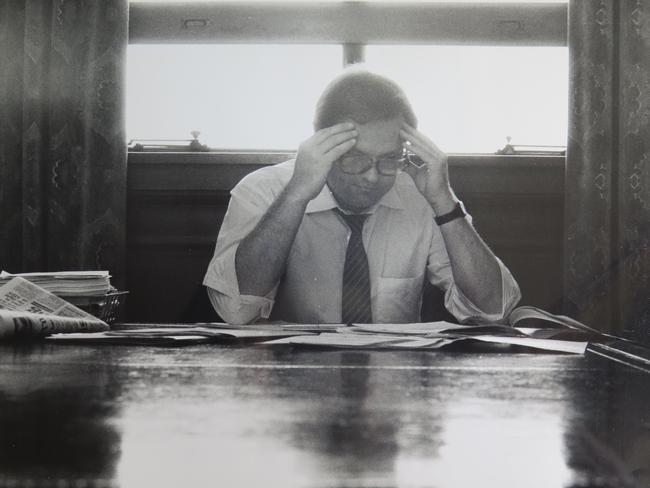

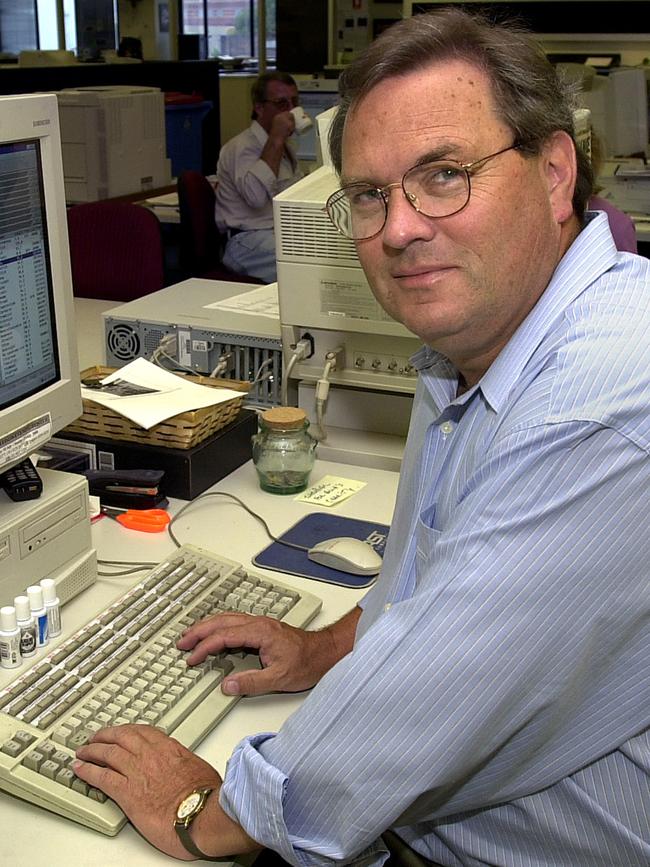

It was this engagement with the world that I always thought made him a great journalist. I want to tell you something: when I was the editor of The Age and Peter was the night editor, he once asked me whether I would consider letting him go back to reporting, something he had not done for a long time. It did not happen, I think because Peter in the end could not bring himself to give up a job he loved and because in truth, I did not want him to make the move: I could not imagine trusting and relying on anyone the way I relied and trusted Peter. He was a rock for me and a miracle maker in the daily production of the paper.

We shared our nights and even our very early mornings. There were those nightly and early morning calls from Peter which would always start with: “Michael, did I wake you?” in that deep growling Canadian accented voice of his. He often did wake me, but I never let on because I liked those phone calls, liked him telling me how the miracle producing had gone, what had gone wrong and what had gone right. We had arguments. Sometimes quite fierce arguments. He was frank with me. But I trusted his judgment. And we managed to do what is often really hard in this sort of situation: we became friends. Good friends.

And so it was that Peter did not become a reporter again until he retired and discovered Facebook. Over time, he produced a body of work about his daily excursions into the world, his encounters with strangers and friends, his travels through his beloved Victoria, his reflections on books and music, suffused with a love of his children and grandchildren – there was his enormous pride as well in his daughter Anna’s writing – and sometimes he wrote of his love and admiration for the music my children recorded and performed.

But can I just go back to those meetings in the St Kilda Gardens during the lockdowns? They had a sort of structure. We would touch elbows and then sit down on the bench by the pond, masks on, and Peter would start by asking me about the health issues I had.

Not long after he was diagnosed, Peter convinced me to get my prostate checked. I went. The GP did the infamous test. Sent me for blood tests as well. Sent me off to a urologist because Peter insisted I should ask for a urologist referral, which I did, and then I turned up at the urologist and he wanted to… OK, that’s enough.

Each meeting in the gardens started with Peter questioning me about my test results. He was very pleased when I could report good results. Then he would tell me about his medical news. He was living in the world of medical appointments and tests and procedures – the world of living with cancer – but he was determined to find, within that reality, a life of connection – with family, with friends, with the ducks gliding across the water near where we sat talking, masked but increasingly unmasking ourselves to each other. We were on a journey together, though we knew that our journey was likely to end differently for each of us.

And in our unmasking, we talked about all this, how our journey together would end. I have lived a long life and Peter too lived a long life but I think those times we spent together, those years of our friendship after Peter was diagnosed with that inoperable cancer that he knew would eventually kill him, were, for both of us, life-changing.

And so, to segue back to where I started – and I know and I fear I may have buried the lede – but I do want to go back to that morning, not long before he died, when we were sitting at that outside table of the cafe we had migrated to because the staff were more congenial (OK, attractive) and Peter asked me whether I would be prepared to deliver a eulogy for him if he and his family decided there would be some sort of memorial service. He did not want a funeral, he said. He wanted to be cremated with no service.

-

We would sit on the bench and talk and then watch the ducks in silence. Two elderly law-breakers.

-

By then, we had known each other for more than 30 years, from 1992 when Peter was hired by the then editor of The Age, Alan Kohler, as night editor. I was the deputy editor. On and off from then on we worked together until I left the paper in 2007. And after we both retired from daily journalism – I can’t remember when that was but it feels like a lifetime ago – our friendship continued and deepened.

I do not want to gild the lily too much. Indeed, I do not want to gild it at all. Peter would not have wanted it. He could be trenchant, grumpy, aggressive, stubborn and uncompromising. And I did not always love his politics. But he was charming, charismatic, forthright and honest. And underneath his gruffness and grumpiness he was a kind man who liked the people he worked with, cared about them and never to my knowledge betrayed them.

Would I deliver a eulogy, he asked, if there was a memorial service? I would, I said. But you know better than anyone Peter, I said, that every writer, including a writer of a eulogy, needs a good editor and, by the time I write the eulogy, I said, you – who I always trusted and still trust to do any piece of writing justice – won’t be around to do the work.

We sat in silence for a moment. Then I said: What if I write the eulogy now, in the next few days or whatever, and send it to you to edit? And anyway, aren’t you curious about what I will say?

He looked at me. He smiled. He said he would think about it.

A few days later, we met at St Kilda Gardens. We sat fairly close together on that bench near the pond, maskless and unmasked. Peter was having a reasonable day. He had walked to the gardens, I think (by then his wife Liz was often driving him to our meetings). After I told him that there was no news about my prostate and after he told me that the treatment he was having was not too debilitating, but he feared it was not doing much good, he said no, he did not think that he wanted to see my eulogy in advance of his dying. He wanted to be surprised.

He smiled. I smiled. Two old blokes smiling. Then he said he was sure that I would manage without his help, though perhaps it would not be as good had he somehow managed to edit it.

And so I did not write this eulogy while Peter was alive, and he did not edit it. And I do think it might have been better, structurally improved, repetitions removed, grammatical errors corrected, the lede unburied. But I know that I could not have written this eulogy while he was alive.

Two days before he died, I sat beside his hospital bed and he reached out, his eyes closed and took my hand and held it and his touch was as soft and light as a baby’s weightless touch.

How could I have written about that moment when he was still alive? And anyway, eulogies are for the living. Whatever I had to say, whatever I managed to say to Peter about the journey we had been on, I had said, as best I could. What I did not say to him, but what I believe he knew, was that I loved him.

As we Jews say at a time like this, may his memory be a blessing.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout