Enhanced Games: Is the ‘Doping Games’ the future of sport?

Could the ‘off-label’ drugs Olympic gold medallist James Magnussen puts into his body hurt him, kill him or land him in prison?

James Magnussen wanders down to the North Bondi cafe with a towel slung over one of his enormous shoulders. He’s an impressive specimen – two metres tall, 104kg and ripped. Two women chatting at a table outside fall silent to ogle. He exercises daily and has put on muscle since he retired from being among the fastest humans to have ever dived into a pool.

Magnussen hung up his Speedos in 2019 at the age of just 28 with a drawer-full of Olympic and World Championship medals. And now, at 32, he’s eager to leap back in with the lure of a $1.5 million golden carrot dangling at the finish line. “I’ve never really stopped training,” he says after settling on a berry smoothie. “Not much swimming, but I’ve always stayed in shape. My goal now will be to get my body functioning, performing and recovering like it was in my early twenties. It’s not to be superhuman and go above and beyond. I was right near that world record at my peak … so how do I decrease the effects of ageing, [increase] the hormonal levels and reduce the recovery period to get me performing like I was at my peak?”

The answer is performance enhancing drugs – possibly a cocktail of steroids and stimulants and an injection of high-altitude red-rich blood. Earlier this year, James The Missile Magnussen signed up to be the poster boy for the Enhanced Games – derided by some as the Doping Games – to be held in 2025. When he next competes, chasing the world record that eluded him during his career in regular elite sport, there’ll be no pesky World Anti-Doping Authority officials peering over the cubicle demanding his warm yellow sample jar.

The Enhanced Games organisers claim their testing will monitor the athletes’ health, and all enhancements will be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration – although drugs will be used “off-label” (that’s to say, used in a way they weren’t designed for). The aim of the Games is to see what feats the human body can achieve with a chemical tailwind. They want to shake up the Olympics by tearing up the rule book and creating a slimmed-down, made-for-TV event. Something about it is reminiscent of the way Kerry Packer shook up the staid cricket establishment with World Series Cricket, and the Saudis took on golf with their breakaway LIV Golf tour.

“We want to push the limits of what’s been done previously,” says The Missile, sipping on his smoothie in the Bondi sun. “I haven’t got a gun to my head saying ‘You need to do this.’ There are [Olympic] athletes around the world doing this right now. But for them, there’s a lot of guesswork.” He reckons around 25 per cent of the swimmers he competed against at international events were using drugs. He claims there are sports that are privately owned, like the basketball, football, baseball and ice hockey leagues in the US, that have lax testing regimes and minimal consequences for those who are caught. “Those boys have been dabbling in the dark arts for a long time,” he says. It has allowed athletes in these leagues to perform at their peak into their late thirties and early forties.

“We want to be open and honest, which has never happened before, documenting it and showing that it can be done safely, with the end goal being high performance … that’s the part that excites me. I’m excited about getting back into the water, swimming fast again and documenting the process.”

But there’s another goal of the mega-rich venture capitalists backing the Enhanced Games: they believe it will lead to greater knowledge about ageing – and how to fight it. Says Magnussen: “It will be a test case for the everyday middle-aged man who is trying to decrease that process … The anti-ageing space … is going to be a billion dollar industry for men [and women] who are lacking energy, libido, vitality and are ageing poorly … no one wants to wake up in the morning feeling like shit, having no sex drive and struggling to get through the day without a nap.” The road to eternity, and eternal horniness, will be paved by juiced-up athletes.

Magnussen sees himself as being like a Formula 1 racing car for humanity. “How did they first optimise a four-cylinder engine? They did it in racing cars, and now the four-cylinder engine is putting out more torque than a V8 … and that’s the way it’s going to be for the Enhanced Games.”

So is this the dystopian future for sport, and humanity? Or is it just the future? Are the venture capitalists backing the Enhanced Games the disrupters the Olympics needs, or are they greedy egoists willing to sacrifice the health of athletes in their vainglorious search for immortality? And is there an audience out there willing to pay as doped-up athletes push the boundaries of human achievement to its limits, regardless of the consequences?

“It’s bullshit,” Sebastian Coe, one of the greatest middle-distance runners of all time and now president of World Athletics, says of the Enhanced Games. “There’s only one message and that is if anybody is moronic enough to feel they want to take part in that, and they are from the traditional, philosophical end of our sport, they will get banned … I don’t really [have] sleepless nights over it.” The legendary runner doesn’t believe the concept has legs.

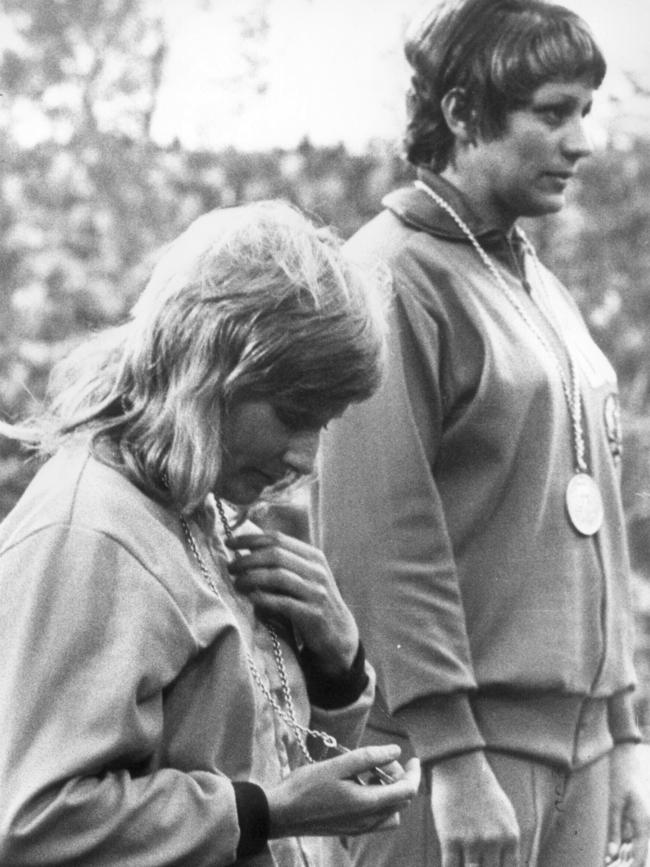

One of our own greats, sprinter Raelene Boyle, tells me she doesn’t have to imagine what this future would look like – she lived through it. Boyle was at her peak as the East German doping regime was its zenith. At the 1972 Olympics she ran second in both the 100m and 200m finals to the East German sprinter Renate Stecher. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Stasi files revealed that Stecher was part of a systematic, state-sponsored doping program. As a PBS documentary on the scandal explained: “It was German, it was orderly, it was bureaucratic, it was written up.”

Thousands of East German athletes were administered steroids, amphetamines and human growth hormones, and had their blood boosted. In the years afterwards many suffered from horrendous side effects – women experienced virilization (exaggerated masculine characteristics, such as facial hair), infertility, miscarriages and ovarian cysts. Many gave birth to babies with severe deformities. Both men and women suffered liver damage, heart diseases and various cancers. In 2016 the German government set up a $40 million fund to compensate these athletes. “So yeah,” says Raelene Boyle. “We’ve been here before.”

“I think it is the most ridiculous thing ever,” she says of the notion. “Humanity needs drugs to make sick people well, not to make well people sick … human beings should be able to compete with each other in a natural format, rather than taking enhancements to make themselves better.”

Boyle says Magnussen is foolish for becoming involved, and it will damage his sporting legacy. Dr David Hughes, the long-time Chief Medical Officer at the Australian Institute of Sport, agrees. “In all my time at the AIS I have never heard anyone talk about winning at all costs,” he says. “Yes, we like to see Australian athletes doing well, but we also want to see sport as a positive influence in people’s lives.”

He scoffs at the idea that athletes using performance enhancing drugs will have wider benefits for humanity. There are three main categories of medications used by those who want to cheat in sport, he says: anabolic steroids or drugs that mimic them; erythropoietin (EPO), which increases production of red blood cells; and stimulants. “In all three of those classes those medications have valid purposes when people have medical conditions, so they are not going to teach us anything being used on high-performance athletes because we already know what these medications do.”

“People have to also think about what they want to be remembered for,” Hughes adds. “I’ve had the great privilege of knowing many high-performance athletes. Some have been extremely successful. But some haven’t been so successful, and just watching their dedication and their commitment and the way they conduct themselves makes you feel proud to watch them compete, no matter how well they go … they are often the athletes I admire the most.

–

“Athletes are looked up to by young Australians … I don’t think the Enhanced Games is going to be a great inspiration for anyone.”

–

However, Dr Benjamin Koh, an expert in sports medicine and sports law at the University of Technology Sydney, says the Olympics projects “the fairytale fiction that no one is taking drugs, which is ridiculous”; he points out that athletes exist in a society where drugs, both illegal and over-the-counter, are widely used.

Koh says there are two types of dopers: the first lot do it through peer pressure, following the example of other athletes and observing a “cone of silence”; he describes this as “the ignorant leading the ignorant”. The second group seeks out every possible drug, legal or illegal, to get an advantage; he calls them “The Lance Armstrongs of the world.”

He says that with every drug there is a risk, “but at least if you are doing it openly you can actively seek advice and make sure you are not overdoing certain aspects”. He envisages a split in world sport, like there has been in bodybuilding where those who don’t want to use steroids compete in self-enforced natural bodybuilding competitions, and the others in the juiced-up version, so there’s no “pretend”.

The man who launched The Missile back into the pool is a nerdy Australian bloke called Aron D’Souza. He was never much of a sportsman as a kid, although he did play rugby at Oxford – but that was as much for the drinking and for the elite connections as it was for the game. Sam Altman, a leading figure in America’s AI sector, described his friend D’Souza, in a 2018 profile in this magazine, as “ruthlessly ambitious” and a “monster networker.”

D’Souza, the child of academics, grew up in Melbourne, with stints in the US and Europe where his father took up research postings.

“Mum and Dad were shareholders in various Australian companies,” he tells me from his home in London. Shareholders were invited to annual general meetings, and this excited the precocious young Aron as the meetings were held in flash city hotels. The catch was his parents mandated he had to read the annual report and had to ask one question.

“I was 10 or 12 years old and was tiny,” he says. “And, of course, the chairman would always call on me to ask a question.” It fostered a love of annual reports and he still has stacks in his office. “They’re really boring, but there’s some really interesting information in them.”

He started reading the reports of the International Olympic Committee. “And I was just like, mate, there is so much money sloshing around in this equation,” he says. “There is so much waste, admitted waste.”

He then started reading academic studies into doping, one of which stated that 44 per cent of Olympic athletes were doping and only 1 per cent were getting caught. “We can debate all day about the efficacy of those studies, but whether it’s 10 per cent, 20 per cent or 44 per cent, it’s an indictment.” And, to top it off, he read that about half the US Olympic team were living in poverty.

“There was a lot of waste and corruption,” he says. “There was a lie at the centre about doping. The bureaucrats are getting paid a fortune and the athletes are getting paid nothing. I knew that that was a system ripe for disruption.” And he’s in the disruption game.

As D’Souza admits, he’s “pretty weird” and each year around Christmas he sits on a beach “somewhere beautiful with my trusty laptop when no one else is working” and writes a business plan with an idea that can “change the world”. In December 2023 he wrote his plan for the Enhanced Games. “I generally spend New Years with Peter Thiel,” the monster networker says. “I told him I was writing a business plan for an enhanced Olympics. And he’s like, ‘Oh that’s really cool.’ And we just left it at that.”

Peter Thiel, of course, is a heavyweight Silicon Valley venture capitalist – a co-founder of PayPal, an early investor in Facebook, and a squillionaire. He and D’Souza go back to 2011 when the young Oxford graduate approached the tech titan out of the blue with an audacious plan. D’Souza knew that Thiel, who is gay, was outraged he had been outed by the US gossip website Gawker in a 2007 article headlined “Peter Thiel is totally gay, people.” D’Souza came to him with a plot for revenge. It led to Thiel secretly bankrolling a $10 million lawsuit for the wrestler Hulk Hogan. Gawker had published tapes of Hogan and his friend’s wife having sex. In 2016 a Florida jury awarded Hogan $140 million in damages, financially annihilating Gawker and its owner, and quenching Thiel’s thirst for stone-cold vengeance.

And so, “That’s a really cool idea” over New Year cocktails in a Miami penthouse was not two mates pledging to cycle more in the coming year to banish their beer guts. Early last year D’Souza flew back to London and put together a team to make the Enhanced Games a reality. “My theory of social change is very simple,” he says. “It only happens when someone puts on a suit and goes to work every day to try and solve a problem.”

For Thiel and Christian Angermayer – another of the billionaire backers of the Enhanced Games – there’s another incentive. They’d like to live very long lives, and, if possible, forever. Angermayer, a 45-year-old German investor, has said that death and ageing is “widely misunderstood” and that it is just a collection of diseases that can be overcome. “Being in control of your own time of death will be the ultimate liberation for humanity,” he said.

In a call from London, Angermayer says we take drugs to cure depression, so why not take drugs to slow the ageing process? “I’m taking testosterone,” he says. “Why would I let [my testosterone levels] go down? The Enhanced Games idea fits in with my view of the world. Why wouldn’t you allow athletes to choose, as long as it’s transparent? The unfairness in doping doesn’t come from doping, it comes from doping in secret.”

Thiel follows a strict, multifaceted regime to extend his life. According to a piece in The Atlantic, he’s on a paleo diet, is thinking of using nicotine patches to improve his IQ, has spoken of using human growth hormones for muscle mass, has taken drugs for weight loss, injects himself with an anti-diabetic drug to suppress the risk of cancer and is not averse to injecting himself with the blood of a younger, healthy person to slow the ageing process. If all that fails, he’s signed up to be cryonically preserved after death in the hope that he can be revived for a second life once medical science has solved the problems of disease and mortality.

Both Thiel and Angermayer have invested millions in the burgeoning “longevity” sector – for the good of humanity – and Angermayer has also placed bets on psychedelics to treat mental health issues like PTSD and depression. No use living forever glumly.

Thiel was a generous donor to Donald Trump and was appointed to the executive committee for Trump’s presidential transition team the first time around. The pair have since fallen out after Trump called Thiel asking him for a $10 million donation for his current presidential campaign, and Thiel refused.

D’Souza says Thiel has made “gargantuan amounts of money” by investing in the future, firstly the internet and now in OpenAI. “Right now this idea of transhumanism, the idea that we can become superhuman, is completely science fiction. But venture capitalists know that the future isn’t a joke,” he says.

D’Souza says Thiel and Angermayer are investing in the Enhanced Games because they believe the Olympics is ripe for disruption.

–

“They know that a dysfunctional organisation like the Olympics can’t last forever and that it is the crown jewel of international sports.

–

“And if it isn’t the Enhanced Games, then it will create the opportunities for enhancing the rest of humanity.”

Angermayer tells The Weekend Australian Magazine that several Paris-bound Olympians have been in serious talks about joining the Enhanced Games.

“We can’t reveal their names yet because they want to compete (in Paris),” says Angermayer.

D’Souza does not always possess the Midas touch. In 2015, along with the Melbourne tech entrepreneur Phillip Kingston, he founded the fintech and superannuation services company Sargon. D’Souza left the company a year before its spectacular collapse, but is still entangled in the fallout. In the world of venture capitalism, though, it’s forever onwards and upwards. D’Souza has set himself up as the Founder and President of the Enhanced Games, “a global movement of athletes who believe in science [that] aims to end the exploitative practices of the International Olympic Committee.”

And so how will this all work? D’Souza says he wants to take drugs in sport out of the shadows. “The dark alley is the bane of safety,” he says. “I know this as a gay man.” He likens it to the HIV epidemic, which was murderous to the gay community because many politicians refused to acknowledge it and talk about safe sex and treatments. “By bringing this into the light and sharing data it will allow all this to become much safer,” he says. “This is a social change project because I believe everyone has the right to be enhanced, not just athletes … if we can overcome our weak, feeble biological forms we can be so much stronger, as a species.”

This will be achieved, in part, through what he calls the third incarnation of the Olympics – the first being the ancient Olympiad, and the second being the modern games run by the “corrupt” and bloated IOC, which he says has been in terminal decline since its peak at the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

D’Souza’s idea is to slim down the number of events to swimming and diving, track and field athletics, weightlifting, gymnastics and combat sports. They’ve yet to decide what to do with Paralympians. Athletes who compete will get a base salary and will compete for prize winnings – with the amounts yet to be announced. Those who break an existing world record will receive a $1.5 million ($US 1 million) cash prize. The events will be held in existing stadiums – probably US college venues – to cut down on costs. He says he was in New York recently, negotiating a deal with US broadcasters to fit in with their scheduling, sometime in 2025. Acclaimed filmmaker Ridley Scott has been commissioned to make a documentary on the “journey into the heart of the Enhanced Games”.

What sort of doping will be allowed, I ask? D’Souza is offended by my language. “Enhancements, not doping,” he chides. “Language matters here … you wouldn’t call a gay person walking down Oxford Street a faggot. So it’s enhancements, not doping.”

“The number one principle is clinical supervision,” he continues. “So everything that an athlete does will be clinically supervised.”

All the substances will have to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. D’Souza won’t reveal exactly which drugs it will allow athletes to use, but the obvious candidates are steroids, EPOs and stimulants. “We are currently developing medical safety protocols which will include details of performance enhancements permitted.” Such drugs have been developed to treat medical ailments, not to make athletes faster, but Angermayer tells me it’s not especially onerous to get around the US regulations. “I have a doctor in America and I have [been prescribed] testosterone, human growth hormones and anabolic steroids,” he says. “So off-label use is possible.”

If athletes are already gaming the system now, I ask D’Souza, why won’t they game your system too? Disputing James Magnussen’s argument that US footballers, basketballers and baseballers have been “dabbling in the dark arts”, he says that these highly-paid athletes have far less incentive than Olympians.

The Olympians “need to cheat to survive” because they have so little chance of financial success unless they win gold. “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome,” he says, quoting Charlie Munger from Berkshire Hathaway.

He says the risks to the athletes from taking their enhancements will be minimised, because it will be done under strict medical supervision. “Lance Armstrong was probably one of the most doped individuals in history – and I use that term in a very intentional way – and he hasn’t suffered any ill health effects because it was all done under clinical supervision.”

D’Souza says the current drug testing regime is not about safety, but about fairness, which is why they call the country’s testing body “Sports Integrity Australia, not Sports Safety Australia … We want to ensure our athletes are healthy to compete … we want to push the boundaries of humanity, but do it safely.”

Back in Bondi, Magnussen tells me that the response from his old mates in the swimming world has been positive. “The main reaction has been intrigue,” he says. “Most people are really interested to see what happens … what we use and how that will affect my performance. Are there any side effects and how do we negate them?” He regrets his comments (made in jest, he says) in a sports podcast in February in which he said: “If they put up [US] $1 million for the 50 freestyle world record, I will come on board as their first athlete. I’ll juice to the gills and I’ll break it in six months.” This, he says to me, was a “sub-optimal line” and now gets wheeled out whenever there is a story about him or the Enhanced Games.

When asked precisely which performance enhancers he’s inclined to use, Magnussen says “I’m not commenting on substance use”. Once a date is announced for the Enhanced Games he’ll begin training, “and then I’ll meet the doctors” to talk about enhancements and the “protocols I need, [the] who, what, when, where and why, and reverse-engineer all that so I’m peaking … for the Games”. He’ll be guided by those doctors and sports scientists and will likely have to move to the US to get drugs directly from the manufacturers. Anabolic steroids can only be prescribed by a licensed physician in the US, and those without a prescription face a one-year prison sentence. The FBI has a unit focusing on these issues. Magnussen says he will only use what can legally be prescribed as he chases that juicy $1.5 million bonus.

There’s a generational split in the debate, says Magnussen, who has worked as a media commentator, opened a gym and appeared on Dancing with the Stars, among other things, since retiring from competitive swimming. Young people are generally on board with the Enhanced Games concept while older people are more sceptical, he notes. He likens it to the reactions to LIV Golf. “Most of the guys I work with in their fifties and sixties say it is dirty Saudi money, it’s rubbish, it’s not the real form of the game and people’s legacies will be tarnished. Young people go, ‘What a great product, I watched it on TV.’ Some went to Adelaide to watch it live. All the athletes are being paid more … it was all positive.”

He’s revving his engine. He’s ready to race. Will he be an F1 car for mankind, or a crash test dummy for the human ego? Buckle up, it’ll be a wild ride either way.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout