In 1936, the actress Bette Davis had a point to make. She did so at the 8th Academy Awards at which she collected her Oscar for Dangerous in an outfit filched from the costume department of the 1934 film Housewife. The blue and white dress with matching jacket, a creation from the Australian designer Orry-Kelly, was intended for characters playing the “hired help”. Davis, caught up in the studio system of Hollywood’s golden era of the 1920s and ’30s in which actors, directors and writers were under contract to a specific studio, felt she could relate.

“She was really vilified for [the choice of dress] by the press and by the industry,” says Dijanna Mulhearn, author of the forthcoming book Red Carpet Oscars. “But she had a point to prove, and she really proved it – it really made people start to realise, ‘Hang on a second, these stars are not autonomous. They don’t have freedom of choice.’ That was the seed of her saying to the industry and the world, ‘No, we are going to take control of our careers more. We’re not just going to do the movies that you’ve told us to do to fit a personality that you are telling the world we are, which we are not.’”

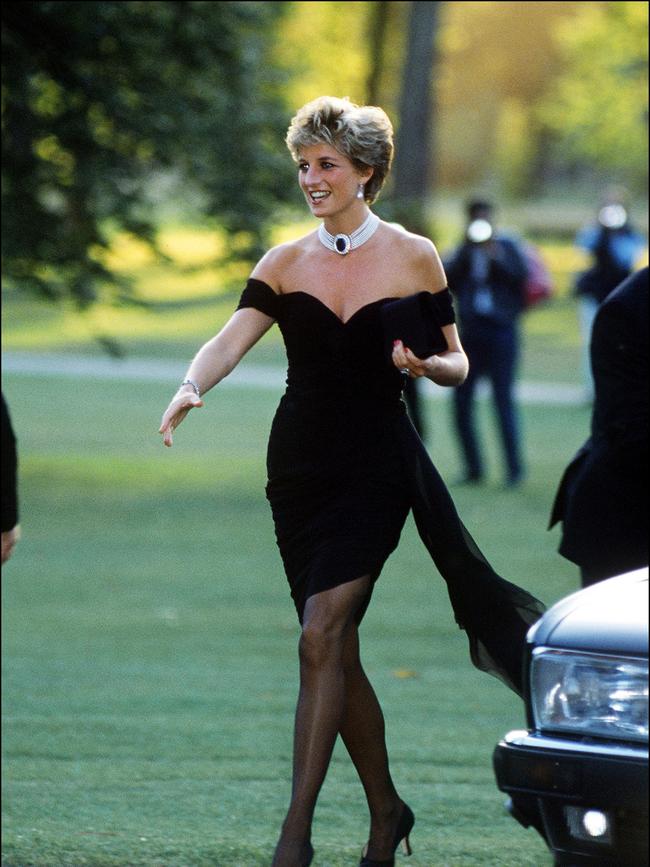

Davis’s so-called “unsuitably gowned” moment was not only “protest dressing”, well before the late Princess Diana’s infamous black off-the-shoulder “revenge dress” in 1994 and any one of the pins worn by celebrities for any one of their causes, but also cemented the idea that since its beginnings in 1929 the Oscars has been the ultimate billboard.

What’s more, as Mulhearn notes in the book, the red carpet and the Oscars – still the peak of awards season and show business’s most glamorous night, despite the advent of prestige television – reflects and distils shifts in society. Note the return to Old Hollywood’s flouncy femininity in the 1950s as society encouraged women to return to domestic spheres after the all-in and ultra-lean war years. Cut to the modern day and the vision of actor Billy Porter in a custom Christian Siriano black velvet gown in 2019, which Mulhearn declares was “probably the biggest moment in Oscar fashion history”. “The thing I love about it is with Billy [and Siriano], it was a chance meeting, they decided to take this risk and Billy Porter came out saying, ‘I’m not a drag queen, I’m just a man in a dress.’ I think that’s the most important thing I’ve heard in fashion in the last 10 years.”

Frequently featured in the book is Australian actress Cate Blanchett, whom Mulhearn admires for red carpet risk-taking. In a foreword to the book Blanchett writes of her long-held fascination with dressing up, which began in the suburbs of Melbourne. “When I was unexpectedly catapulted into the fray, I found myself in a wonderland of fashion,” she writes. “The Oscars red carpet has always seemed to me to be a high-profile intersection between fashion, visual art and theatre, so where better to showcase their dramatic creations? The clothes were nothing short of spectacular, and in a world full of street grunge, the operatic red carpet seemed one of the few places to wear them. Win or no win, the dress itself, whether loved or reviled, is a receptacle of memory and an exquisite reminder of the personal pleasure of this moment.”

Mulhearn says Blanchett innately understands the power of clothes. “[Blanchett] is incredibly brave… She takes risks and she owns them… She thinks a little deeper about it than people who are newer to the game, or people who don’t fully appreciate or understand the language of clothing.”

The Academy Awards, which, like many a good thing, started as a dinner party, was first televised in the early 1950s. Though Mulhearn says the 1960s, an era of free love, Mary Quant mini-skirts, Barbarella and Liz Taylor and Richard Burton’s torrid love story, was a key moment for Oscars fashion as a distillation of a changing world. Here hourglass silhouettes were swapped for empire waists, and even, as for Julie Christie at the 1967 ceremony, a mini-dress – an audacious choice for the time and place. Indeed, it not only made the audience gasp, but signalled an unpicking of dress codes and values.

Next was the flower-power 1970s and ostentatious ’80s in which the adage the puffier the sleeve, the closer to God was fully realised. Nobody understood the memo of excess – albeit often in incredibly scanty ways – better than Cher, who dominated the red carpet in glitzy designs by the US fashion designer Bob Mackie. Mackie told Mulhearn he occasionally questioned whether it was “too much”. Cher’s response, always: “No, it’s not enough.”

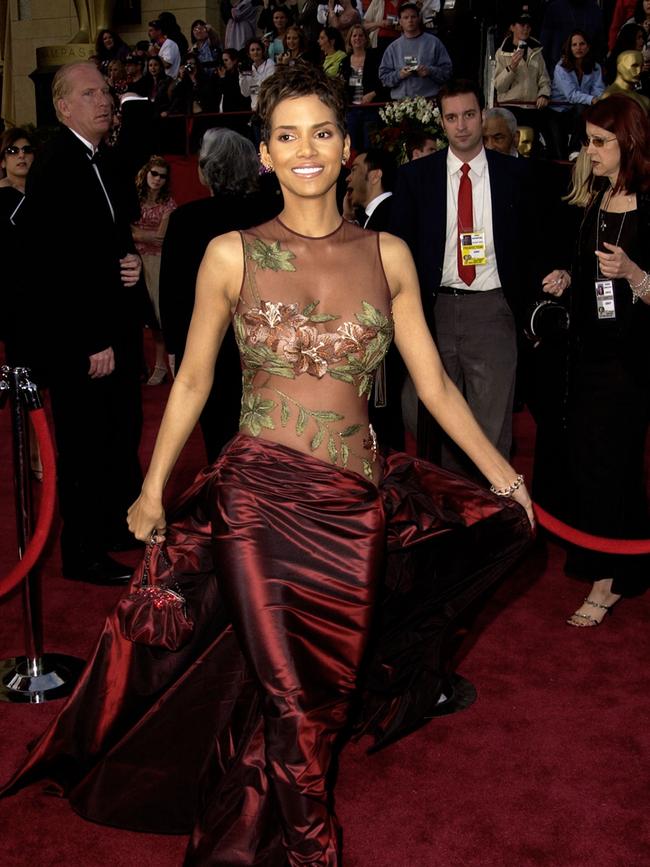

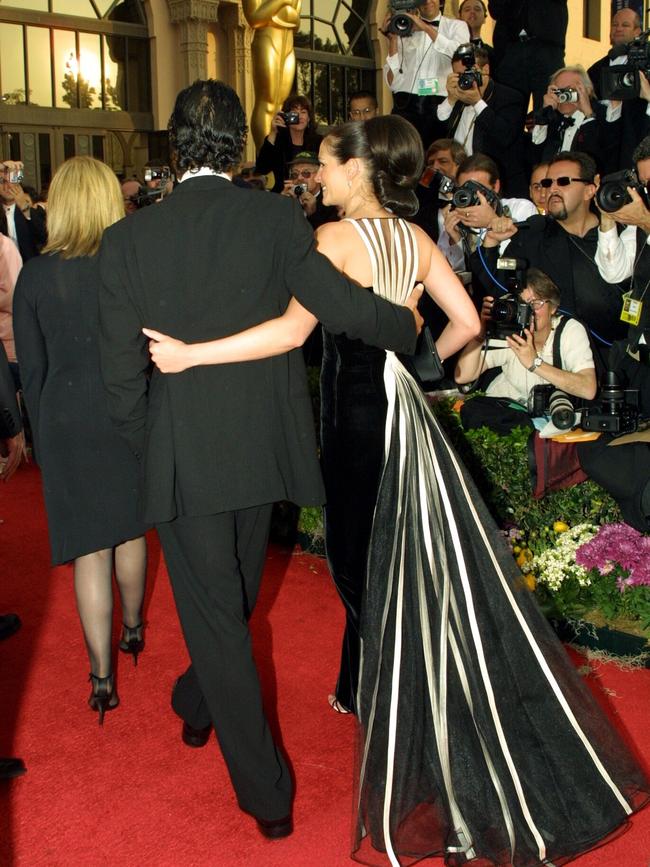

Cher understood the power of a successful red carpet moment. As Mulhearn notes, from Julia Roberts’s vintage Valentino gown in 2001 to Angelina Jolie’s much-memed, leg-baring power pose in her Versace number in 2012, the right choice can rocket one’s career. This can be the case for a designer, too: think Halle Berry creating global acclaim for Lebanese designer Elie Saab when she won the Oscar for Monster’s Ball in 2002 in a sheer burgundy gown adorned with flowers.

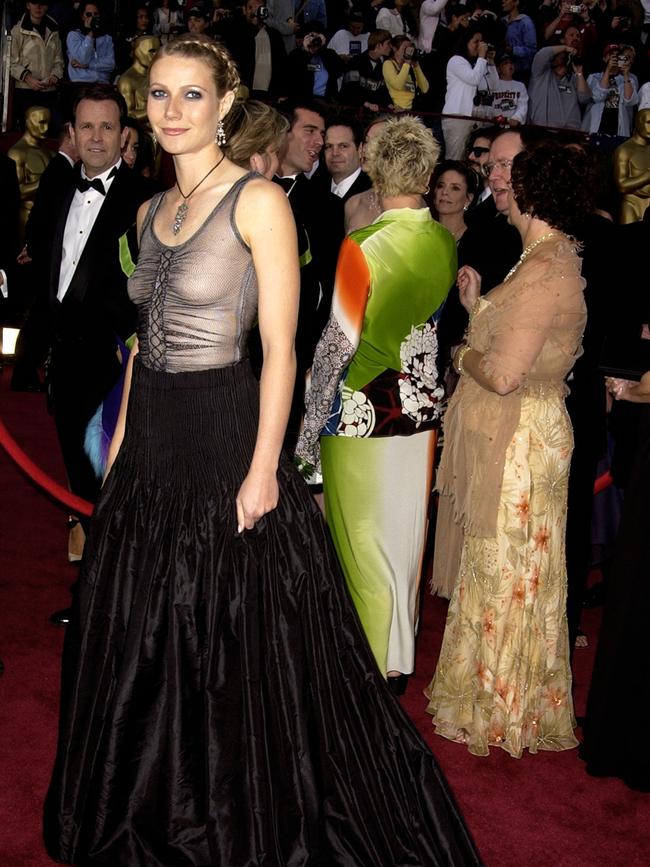

Though as Gwyneth Paltrow can also attest, a derided look such as the black, see-through Alexander McQueen she wore in 2002 can also enter one into the annals of fashion history. Paltrow remains mainly unbothered by the fuss. In a video interview for US Vogue in 2021, she said of the look: “I had a weird hangover about it for a while because people were really critical. I think at the time it was too goth, I think people thought it was too hard, so I think it sort of shocked people. But I like it.”

Another socio-economic transition mirrored in fashion on the Oscars stage was the advent of the recession-hit ’90s. This is when Italian designer Giorgio Armani tamed the excesses of the ’80s with his switch to pared-back elegance. Armani, who also contributed an open letter to Red Carpet Oscars, and is an avowed lover of the movies, dressed the likes of Julia Roberts, Glenn Close, Jodie Foster and more. When she is asked which designer has had the biggest impact on Oscars red carpet fashion, Mulhearn immediately refers to Armani. “I think the biggest moment is the ’90s and George Armani bringing in that minimalist aesthetic,” says Mulhearn. “[Actresses] were looking for ways to be taken more seriously and Giorgio Armani came up with the solution. Yes, you could look incredibly chic without looking like a mirror ball.”

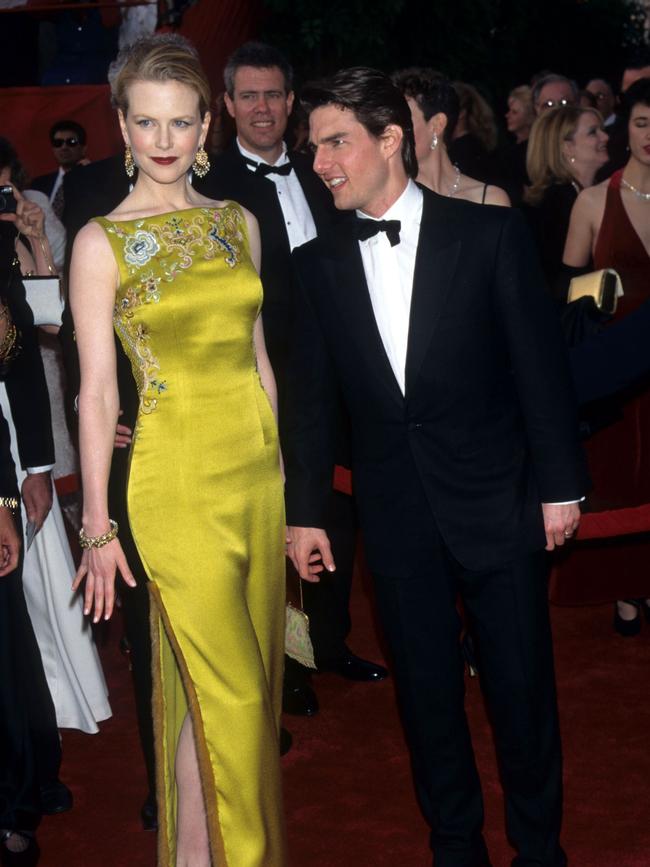

The rise of the red carpet fashion critic around this time, most notably the late and acid-tongue nonpareil Joan Rivers, also terrorised some actresses into more subdued choices. Who could forget Rivers’ reaction to Nicole Kidman’s chartreuse dress by John Galliano for Dior: “I hate that colour! You are making me puke!” As Mulhearn writes, in reaction to this the personal stylist gained prominence and so too the commercialisation of the Oscars red carpet with fashion houses and celebrities striking suitably beneficial arrangements.

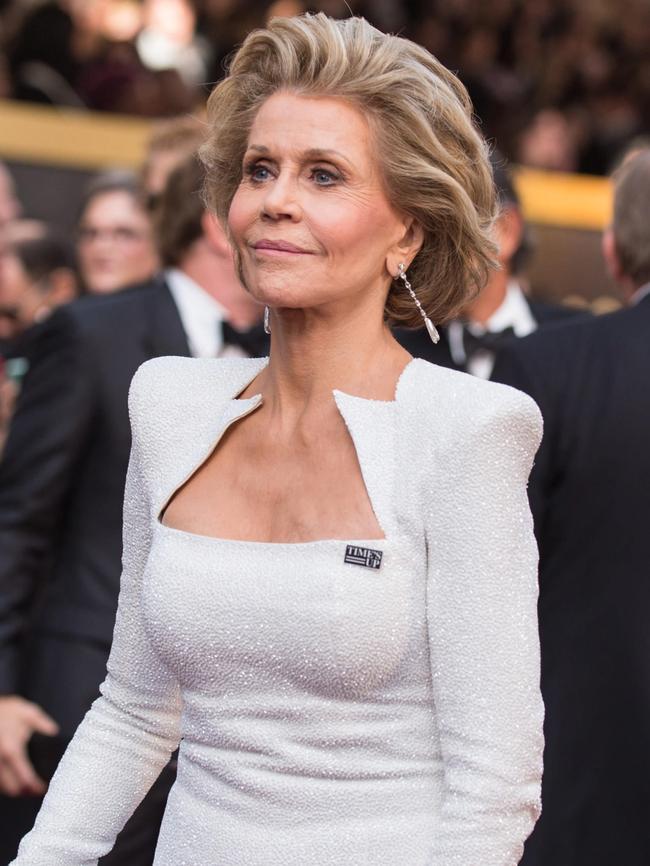

Still, throughout its history the Oscars red carpet has been a hotbed for both tepid and searing protest, whether it’s the #AskHerMore movement of the mid-aughts that pushed for actresses to be asked about more than what they were wearing or “GI” Jane Fonda, an outspoken opponent to America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, wearing a sober black Yves Saint Laurent suit in 1972 as a reflection of sombre times. When she collected her award on stage for Klute, Fonda simply said, “There’s a great deal to say and I’m not going to say it tonight.” Her point, like Bette Davis’s in 1936, had been made with her clothes.

Mulhearn believes we’re in another potent moment now. This includes the likes of Timothée Chalamet challenging ideals of femininity and masculinity with his skin-baring and luscious choices and Kristen Stewart wearing (Chanel) shorts and a tuxedo blazer to the 2022 ceremony. Mulhearn believes this “anything goes” era will usher in a new realm of personal expression.

“I love all of these risks because it makes it OK for everyone to not feel intimidated by fashion… That’s the best thing about the Oscars right now… There’s maybe two or three major shifts where the next generation takes over and we’re in that moment now. It’s their moment and they own it and they’re coming in like a steamroller.”

Red Carpet Oscars by Dijanna Mulhearn (Thames & Hudson Australia) is out on Tuesday

Annie Brown is watch and jewellery editor across The Australian's prestige and Conde Nast titles. She has worked as a luxury and fashion journalist for 15 years, covering all aspects of the industry. Prior to joining News Prestige Annie worked at The Sydney Morning Herald. Her journalism has been published in The Australian Financial Review, The South China Morning Post and fashion titles both in Australia and around the world.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout