Dr Karl Kruszelnicki: why I once became a paranoid prepper

He’s a trusted science communicator and debunker of conspiracy theories. So how did Dr Karl Kruszelnicki become a doomsday prepper who believed Sydney was about to be swamped by a massive tidal wave?

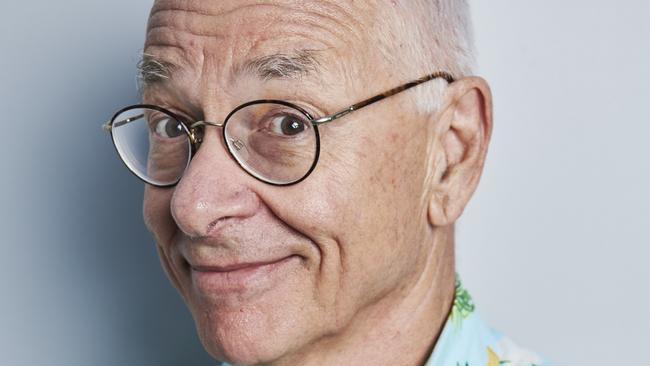

If Australian science had a public face it would be a bald and bespectacled dome atop a bright and busy collared shirt. It would be the face of Karl Kruszelnicki. Dr Karl, as he is known, has been talking science to everyday Australians for more than four decades. His talkback radio career began in 1981 and his science hour on Triple J remains the youth station’s longest running segment. He’s authored 47 books about science, has worked extensively in print and television media and has degrees in physics, mathematics, biomedical engineering, medicine and surgery. Now 74, he still works a packed week – including regular high school talks and appearances on up to eight radio stations – and has a sparkle in his eye that could start a bushfire.

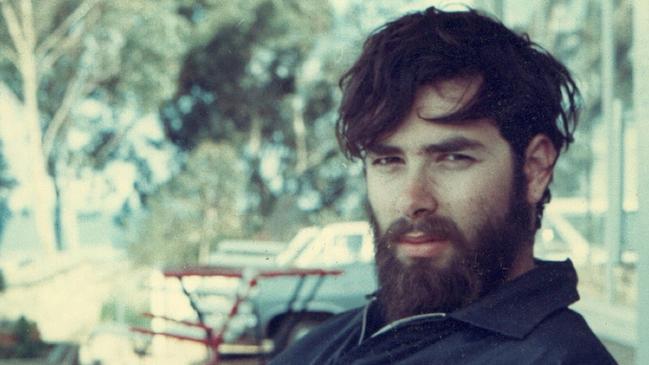

But there are other sides to Karl Kruszelnicki that are less well known. There’s baby Karl – full name Karl Sven Woytek Sas Konkovitch Matthew Kruszelnicki – born in Sweden to Polish parents who escaped the Holocaust. There’s roadie Karl, who hauled speakers for rock’n’roll legend Bo Diddley. There’s indy filmmaker Karl; tech entrepreneur Karl, who helped build Australia’s first cable television station; ditch digger Karl and taxi driver Karl. Most surprisingly, in the early ’70s there was hippie Karl the doomsday prepper who believed Sydney was about to be swamped by a massive tidal wave and fled to the Blue Mountains with like-minded friends, a sack of rice, some kerosene and 20 litres of water. Karl the illogical. Karl the follower. Rabbit-hole Karl.

The tidal wave, of course, didn’t arrive. Karl and his hippie friends celebrated their unexpected good fortune, had “a lovely time” and then returned to Sydney and eventually to reality. Now, looking back, Kruszelnicki says he became a paranoid prepper not because he fell for pseudo-science or was persuaded by a controversial book. “I believed simply because my friends told me about it. That was enough; because my friends were so convinced, I took that as a very high authority.”

Kruszelnicki had already completed a science degree and was working as a physicist when he took the misturn into irrational belief. How did he become so spectacularly derailed? What was he thinking? “I wasn’t thinking,” he says. “Trusting information from a friend [rather than an expert] is a well-known factor in psychology. It’s why peer recommendations are more persuasive than advertising. It’s because we are social animals and we have to get along in order to survive. I was a smoker back then too and I’d heard about the Surgeon General’s health warning but I didn’t accept the science until a friend advised me to quit.”

A tsunami of research has been devoted to conspiracy thinking and extreme beliefs in recent years. The dismissive idea that only “crazies” fall for fantastical untruths doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. We now know that far-fetched lies spread faster and are easier to digest than plodding, complicated truths. The internet and social media have supercharged this phenomena; a 2020 study by Carnegie Mellon University of two million tweets about Covid-19 found that 45 per cent of the Twitter accounts they came from were likely managed by bots rather than real people.

We can also extrapolate that hippie Karl was lucky. Although he was convinced a tidal wave was imminent he held the illogical idea lightly and let it go easily. If he was ever truly down a rabbit hole he was but a bounce from the surface. Conspiracies were part of the counterculture craziness of the time: sex, drugs, and killer tidal waves. But for families who’ve lost loved ones to all-consuming conspiracy belief, helping them return to reality can be as difficult as a cult extraction. In extreme cases, conspiracy belief can lead to tragedy. Last year, Californian surf instructor Matthew Coleman says he became so fixated with macabre ideas he’d gleaned online that he killed his two infant children. He later told the FBI he’d been influenced by the QAnon conspiracy movement and had come to believe his wife had serpent DNA which she’d passed on to the children.

Confusion, isolation and fear generated by the pandemic have provided fertile ground for cognitive misdirection. “Genetically we’re wired to pay more attention to bad and dangerous things,” says Kruszelnicki. “So if you read [QAnon’s theory] that the world is run by devil-worshipping, baby-killing pedophiles, you pay attention because that could be a threat to your existence. So bad news – scary news – spreads six times faster than good news. And it makes sense; it’s a survival thing.”

Conspiracy theories and disinformation are nothing new. Just as corruption and corporate malpractice are depressingly familiar. Kruszelnicki was smacked in the face by the real world shortly after he started out as a physicist aged 19. While working at a steelworks he says he was asked to fake some results on the steel going into Melbourne’s West Gate Bridge. “I wouldn’t do it. I resigned and went to New Guinea and there my boss wanted me to fake results for his PhD and I refused.” Disgusted, he dropped out of the science world to become an independent filmmaker.

His hippie-filmmaker, taxi-driver phase lasted about five years but by the end of the 1970s he had shelved his tie-dyes and rejoined the world of verifiable facts and hard-won knowledge. He earned a Masters in Biomedical Engineering and worked for ophthalmologist Fred Hollows, designing and building a machine to diagnose eye diseases. In his early thirties, restless for more knowledge, he studied medicine and after graduating in 1986 began working in Sydney hospitals. “I loved working in the kid’s hospitals – it was horrendously long hours but I was learning heaps.”

He might still be doing the rounds today if it wasn’t for a fateful tragedy. “A baby died of whooping cough in our hospital and it completely shocked all the staff. At that time the number of whooping cough deaths was close to zero and had been for 20 years.” According to official records, whooping cough killed on average 290 Australian babies each year in the early 1900s before vaccinations reduced the death rate to close to zero by the 1960s. Vaccination rates dropped in the ’80s, says Kruszelnicki, and he links this trend to a popular TV current affairs program that he says misrepresented the science. In his mind, it’s a straight line of cause and effect: misinformation, compromised herd immunity, dead baby. “I won’t name the journalist but I confronted them in the green room a few years later and told them they were now responsible for the death of many babies and the misery of thousands of adults who’ve caught whooping cough,” he recalls. “And the reporter shrugged it off and said, ‘We just wanted to show both sides of the story’.”

It was enough to cause Kruszelnicki to make a career shift from full-time medicine to science communication. He’d already started his talkback segment on ABC radio station Double J and presented the first series of the ABC-TV science show Quantum. In the 1990s he ramped up his media work and wrote dozens of books that debunked myths and encouraged inquisitiveness. He never patronises a talkback caller or dismisses their question. When stumped, he’ll employ the underused phrase “I don’t know”.

Over the years he’s noticed an uptick in fringe ideas. “I’ve been answering science questions for about four decades and I’ve always been a conspiracy magnet,” Kruszelnicki says. “Beginning around 2010 I noticed a real kick in conspiracy questions which I put down to the introduction of the smartphone. Before the smartphone, parents were able to monitor what ideas their kids were receiving and had some control. But after 2010 parents no longer had that ability.” The decade from 2010 onwards has also seen the voracious rise of alternative media sources and fake news. Whatever your opinion – aliens run the world, planet Earth is a flat disk – you could find an online group to validate it and “science” to prove it.

Kruszelnicki is the first to admit that scientific evidence is no match for misinformation and conspiracy belief. In fact, psychologists have shown that berating someone with facts and evidence can have the opposite effect and drive them further into their mistaken belief (the backfire effect). If someone had tried to stop Karl and his hippie mates from fleeing the imaginary tidal wave with facts and evidence, it’s unlikely that it would have made a difference. They were believers persuaded by a scary narrative, insulated from reality by silo-thinking, assured by their group conviction and empowered by their decision to act.

This tendency of humans to make decisions based on emotion and tribal loyalties, rather than cold hard facts, also helps to explain why conveying the complexities of science to the general public isn’t easy. “Most scientists are not good communicators,” says Kruszelnicki. “And why would we expect them to be? It’s two very different skill-sets – like expecting a chef to be a good plumber. So you’ve got to find someone to communicate the science that you can trust.”

“Do your own research” has become the mantra of the internet age but finding “the real truth” online is not as easy as it sounds. “Scientific research takes years just to learn how to do properly,” says Kruszelnicki. “Firstly you’ve got to know how to source peer-reviewed literature and how to interpret statistics accurately. Some people think that doing your own research is watching a YouTube video. If that’s research, what do you call the stuff the scientists do to work out the origin of the universe or how to make wood both transparent and harder than steel? Most of us are unqualified to do [scientific] research simply because we’ve not been trained as a scientist.”

It is easy to make a flawed argument by cherry-picking favourable facts and studies, but it can be arduous and time-consuming to debunk it. “There’s a concept called the Bullshit Asymmetry Factor (BAF) which says that the amount of time needed to debunk a false belief is at least a magnitude longer than it takes to say it. Alan Jones will spend 15 seconds getting it wrong about climate change, but to debunk his claims will take 15 minutes. So that’s a BAF factor of 60.” The 15-second rant gets mass attention, the 15-minute correction puts everyone to sleep.

Kruszelnicki also stresses that we need to stop thinking that intelligent, highly credentialed experts aren’t capable of being dangerously wrong. There will always be maverick doctors and scientists who firmly disagree with the dominant narrative of their colleagues. “Anyone can have blind spots in their knowledge and crazy thoughts,” he says. “I have a colleague who is absolutely convinced the coronavirus does not exist. He believes that thousands of scientists are lying. It’s really hard to talk someone around once they become believers. You’ve got to spend time with them, listen to them and don’t isolate them.”

Kruszelnicki tends to overwhelmingly side with what the majority of scientists say about their own area of expertise, and treats outliers and their alternative hypotheses with caution – especially if they bypass peer scrutiny. But as we’ve seen throughout the pandemic, even peer-reviewed science isn’t infallible and can be interpreted differently by different experts. Science is constantly evolving but it’s a slow process compared to how rapidly a virus can mutate or how quickly dark forces on the internet can create a suspicious narrative around things that are demonstrably true. Some people still believe the Port Arthur and Christchurch massacres were staged by government agents using actors. In the early stages of the pandemic, as many as one in five of your friends and neighbours believed it wasn’t real, or was planned by Bill Gates, or that 5G towers were being used to spread the virus. Another survey found that Australians were the world’s fourth-biggest spreaders of QAnon’s dark nonsense.

What everyone who develops and shares these exotic falsehoods seems to share is a refusal to take responsibility for the damage they can cause. US broadcaster and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones once convinced thousands of his followers that the horrific massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School was faked. For years afterwards the families of the 26 victims were harassed by Alex Jones fans. Jones later admitted he was wrong.

“Deplatform the bastards,” says Kruszelnicki with enthusiasm. “Alex Jones used to have millions of followers until he was booted off YouTube. Now he’s on a lesser platform and he’s got 100,000 followers and they’re all kooks. So deplatforming works. Google allows lies to be spread because that’s how the business profits. Every time you click on a page, between three and 15 gigabytes of data of your personal details become a product which Google sells to advertisers. Social media companies and Amazon follow similar models. You’re not the customer on these platforms, you’re the commodity.”

Kruszelnicki is currently working on his 48th book and his first memoir. “I’m a bit embarrassed but I’m doing it anyway,” he says. He seems extraordinarily busy, but says his workload has slowed. “I used to be able to put in four or five 16-hour days in a row,” he says. “Now I can only do 12 or maybe 14 hours working solidly on one thing.”

At some point I realise Kruszelnicki might himself be the answer to the question that spurred this story: how do we fix this misinformation mess? Not with what he says but what he does. Misinformation experts say we need to start treating junk information as if it’s as bad for you as junk food. Karl eats his metaphorical greens. “Most of my working week is spent reading scientific papers and journals. You’ve probably heard of the knowledge pyramid – you start at the bottom with data, which leads to information, which leads to knowledge and on to wisdom. Data is the foundation. Much of science is spent getting the data right. Research can take weeks or even years. If you input the wrong data you’ll almost always end up with bad information and corrupted knowledge.”

Over the past 40 years Kruszelnicki has become a trusted expert at debunking false ideas, but more importantly his career has been devoted to “prebunking” or getting the most authorative science into the public arena before it’s tarnished by punditry and propaganda. He has a robust moral compass: there are absolute rights and absolute wrongs in the world of Karl Kruszelnicki. And while there is freedom of speech, it comes with the crucial caveat that every individual – doctor, scientist, journalist, social media influencer – is responsible for the ideas they put out into the world. Get it wrong and there are consequences. Have your say but own the results.